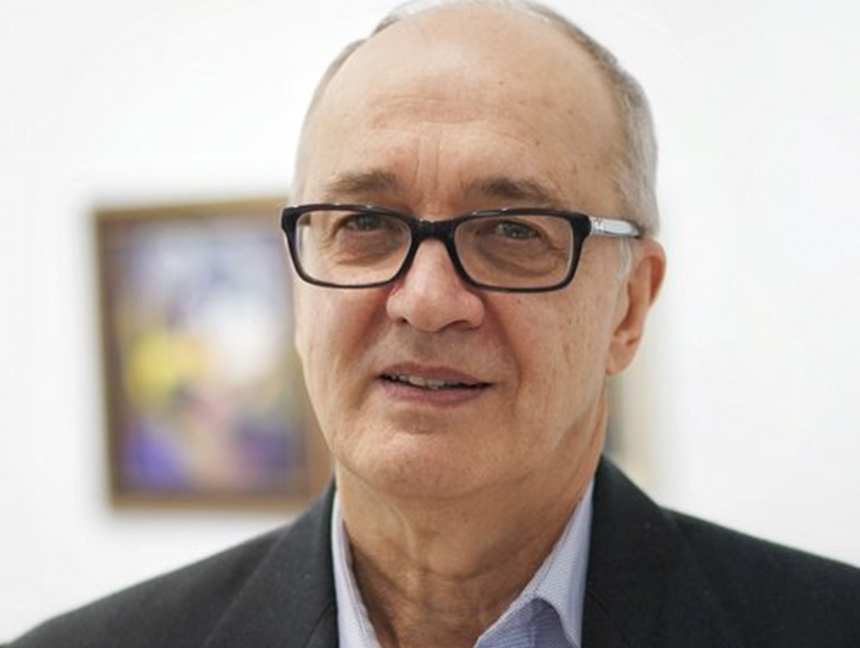

Myroslav Shkandrij: “There are problems in Ukraine that are challenging historians, writers, and civil society”

How did the stereotype of the “keys to the church” arise? Was Taras Shevchenko an antisemite? Who was the first Jewish voice in Ukrainian literature? And why did Jews in the shtetls keep Ukrainian theaters sold out? These and many other questions are raised in an interview with the literary specialist and professor of the University of Manitoba Dr. Myroslav Shkandrij, guest lecturer of the Master’s Program in Jewish Studies at Kyiv-Mohyla Academy.

[Ivan] Kotliarevsky’s Eneida, written in 1798, is regarded as the first work of modern Ukrainian literature. In what context do Jews appear in this poema?

I was pleasantly surprised that, for example, Kotliarevsky’s reference to a tavern, where a woman is going to a dance, does not convey any negative connotations. Such an approach is maintained in the description of hell, where robbers and various types of sinners are sitting. It’s a full international crowd, where Jews do not stand out from the general population at all, even though they are there.

It won’t be long before the image of the Jew becomes sinister thanks to the cliché “keys to the church,” which Jewish leaseholders kept with them in taverns, and handed over to the Orthodox for a bribe. How did this stereotype come about, and does it have a basis?

I found the original source of this cliché in Istoriia rusov ili Maloi Rossii [The History of the Rus′ People or Little Russia], which was published in the Russian language in 1846. Admittedly, it’s about the events of 1648, although in documents from the [Bohdan] Khmelnytsky era the theme of “keys to the church” is practically nonexistent, nor does it appear in religious polemics of that period. Even in the most anti-Jewish text of the seventeenth century, Mesiia pravdyvyi [The True Messiah] by Archimandrite Ioannikii [Galiatovsky] there is no evidence of anything like this.

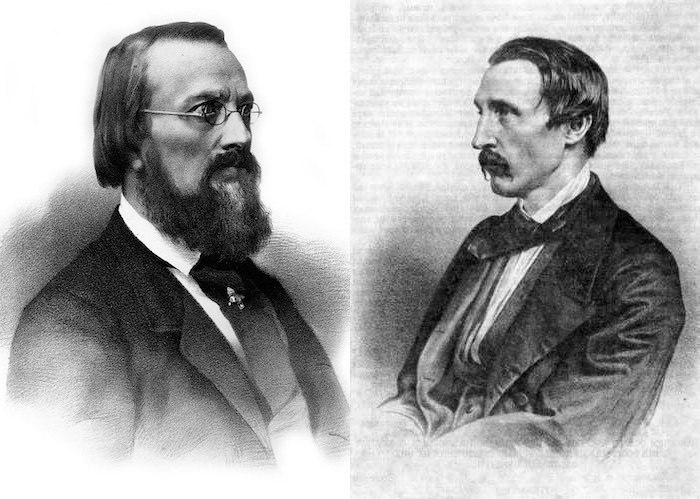

This begins to be “remembered” only in eighteenth-century Cossack chronicles, and the stereotype was ultimately formed in the 1840s, thanks to Mykola Kostomarov and Panteleimon Kulish, who canonized it in their works. To confirm the authenticity of this story, they cited folklore, in particular the “Duma about Ukraine’s Oppression by Jewish Leaseholders” and the “Duma about the Battle of Korsun.” Admittedly, the first duma was recorded by Kulish himself, who had the habit of editing original materials at his own discretion.

For example, he embellished, with supplementary details, scenes of outrages perpetrated against the Orthodox. It is precisely for this reason that in his work Polish priests move between villages supposedly not on horses but on the backs of people. All Orthodox churches are rented out to Jews. Jews accept keys to churches and ropes from bells, they bring them to taverns and allow Christians to hold liturgies only for “big money.” Jews sell vodka in churches and bake paskas, etc.

Was this stereotype justified? The historian Judith Kalik of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem has analyzed its basis. Sometimes Catholic landowning magnates would close churches if the peasants failed to pay their debts. Responsibility for the collection of such debts, as well for tax collection, was often placed on Jews. But they did not rent churches—that’s a myth, corroboration for which was not even uncovered by Mykhailo Hrushevsky, who also found this story suspect.

Furthermore, we’re talking about a general standard for Jews, Catholics, and Orthodox. If you are in debt for land rent, then your synagogue, [Orthodox] church, or Catholic church is closed until the debt is cleared.

I will add that for the most part this pertained specifically to Roman Catholic churches, but you will not find a single word about this in Ukrainian literary works of that period. This fact was complicated and actually dismantled the stereotype of the “keys to the church.” Therefore, it was simply ignored.

Why was this anti-Jewish speculation so readily taken up by Ukrainian enlighteners, like Kostomarov and Kulish?

During the period of romantic nationalism, many writers, including Gogol, paid tribute to such clichés. All over Europe, there was a vogue for everything that had to do with the native folk, within the framework of which our tradition—and only ours—is profound and majestic, meaning, it is necessary to find the one who is oppressing it.

That’s why Kulish—and Kostomarov—developed the theme of the evil Jewish leaseholder forbidding the Orthodox to serve in churches, and the latter expunged from the popular epos absolutely everything that did not fit his notion. [Ivan] Franko notes that in Kulish’s recording of a particular duma, the words “the gracious lords, the Liakhs” [Poles] were replaced everywhere by “Jewish leaseholders.”

At the same time, Kostomarov opposed the first design of the Bohdan Khmelnytsky monument in Kyiv, which depicted a Polish nobleman, a Jewish leaseholder, and a Jesuit beneath the hooves of the hetman’s horse.

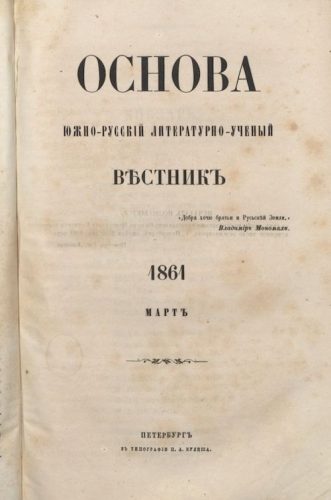

When did discussions begin about the normative nature of the word zhyd [Jew] in the Ukrainian language, the right to the free use of which is still championed to this day by some Ukrainian patriots?

In 1860–61 a great debate on this subject unfolded in the pages of the Ukrainian journal Osnova [Foundation] in St. Petersburg. Ukrainians insisted that the word zhyd in Ukrainian was exactly the same as in other Eastern European languages: entirely neutral. Jewish journalists agreed that everything depended on context, but already by the late nineteenth century, such authors like Lesia Ukrainka preferred to use ievrei instead of the traditional zhyd.

In Greater Ukraine, the word ievrei became normative, partly thanks to writers who used it. In Galicia, zhyd remained the norm much longer, but today this question has been resolved.

Taras Shevchenko’s attitude to the Jews is a topic on which much ink has been spilled. Nevertheless, can we call the Kobzar an antisemite, or was he simply a man of his time with all his ideas about “strangers”?

Shevchenko is a unique figure, on a grander and deeper scale than Kostomarov and Kulish. Unfortunately, he is read inattentively, and this has already become a tradition. Shevchenko wrote in various voices that sometimes overlapped each other. His works contain up to seven or eight narrators, and they are constantly switching.

He recorded antisemitic sentiments, for example, in Haidamaky, but this epic poem is more complex than it would appear at first glance. Yes, Leiba exploits Yarema, but later they go together to the Polish camp and spirit away Oksana. Dressed as a haidamaka, Leiba helps Yarema, and in another episode Yarema the avenger rides past the village where he had been Leiba’s servant, and he feels nostalgic. Everything is very strange; there is confusion in the reader’s mind.

Actually, Ukrainian-Jewish relations were much more intimate than we imagine. Shevchenko understood this, and he conveyed this intimacy of cultural interaction. In addition, his views underwent a certain evolution.

In this context, I often recall Bahrytsky’s “Duma about Opanas.” It is written in the same rhythm and style as Haidamaky. There is also a plot analogy: a confrontation between a Ukrainian peasant and a Jewish commissar. Without doubt, they are enemies, but enemies who understand each other perfectly and who have a deep connection. Critics often fail to spot this connection, but it is a fundamental one, and it allows us to understand why Jews in Ukrainian literature are depicted differently than in Russian literature; precisely because we are neighbours…

During the second third of the nineteenth century, we are faced with an amazing phenomenon: the participation of individual Jews in the Ukrainophile movement.

Yes, this was a period marked by the encounter between the Ukrainian and Jewish intelligentsia within the framework of the movement for civic rights, to use a modern term. In this context, it is worth mentioning the banker Vsevolod Rubinstein, the financial supporter of Ukrainian circles, and Viliam Berenshtein, a baptized Jew, who was the editor of Shevchenko’s works.

The trade and industrial elite—big sugar manufacturers, bankers, and railroad barons—began to develop cities and urban culture. Jewish and Ukrainian patrons began to make contact with each other more often, and in the 1880s philosemitic notes appear in depictions of Ukrainian-Jewish relations.

In the early part of the twentieth century, against the background of state antisemitism and a wave of pogroms, the attitude to the Jewish question became a marker of liberalism and free-thinking; at any rate, for Russian writers. What did Ukrainian writers and journalists think in this regard?

Publications like Hrushevsky’s Ukrainskii vestnik [The Ukrainian Herald], which began to appear in St. Petersburg in 1906, and the journal Ukrainskaia zhizn [Ukrainian Life], published in Moscow through the efforts of Symon Petliura, sympathized with the Jews’ struggle for equal rights. During the Revolution of 1905–1906 Hrushevsky wrote that Jews, like Ukrainians, are victims of foreign domination, and he insisted that the Duma consider a law to abolish the Pale of Settlement. The lawyer Arnold Margolin (later the Directory’s Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs) enjoyed the broad support of Ukrainian circles during the elections to the First State Duma.

For many Ukrainian writers, Jewish biblical history became a metaphor for the struggle against oppression. I must emphasize that I am not talking about the popular masses, but about a thin stratum of intellectuals who began to dismantle the stereotype of the “keys to the church,” creating along the way a sentimental image of the poor, humiliated Jew, which elicited sympathy; an image that was partly naïve yet positive.

Theatrical figures played an immense role in cultural interaction. As early as 1878 [Ivan] Karpenko-Kary sought to change the law barring the admission of Jewish children to schools, and during the pogrom of 1881 in Yelysavethrad, he sheltered several Jewish families.

With the opening of the first stationary Ukrainian theater in Kyiv in 1907, plays with Jewish themes immediately appeared in its repertoire. Sadovsky’s theater staged Abraham Goldfaden, Sholem Ash, and Jakob Gordin. The latter’s plays Mirele Efros and Khasia the Orphan enjoyed huge success.

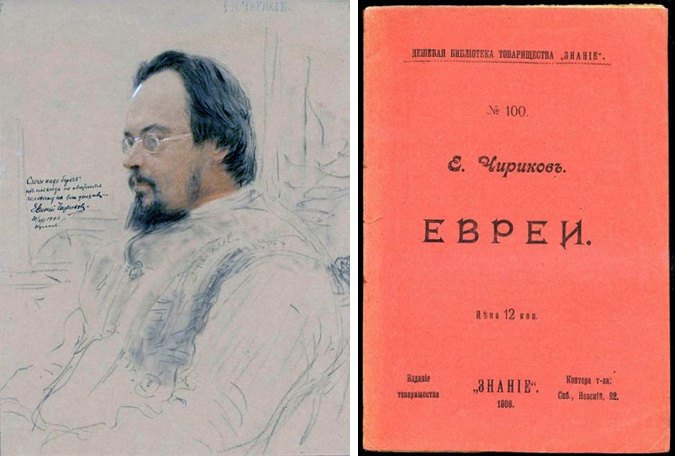

For the start of the 1907 season, Sadovsky prepared Evgeny Chirikov’s play The Jews in a Ukrainian translation, starring the great Maria Zankovetska in the role of Leah, but the censors banned the production. Nevertheless, the premiere, which was a response to the pogroms of 1905, took place the following season. Evidence exists that this play had an impact on two future greats of the Ukrainian theater: Les Kurbas and Hnat Yura.

Published in 1907, the Ukrainian translation of The Jews included a foreword by Symon Petliura, who noted that “Nachman’s sufferings elicit profound sympathy in everyone, whether or not he belongs to this people, the historical fate of which became a heavy cross of oppression and violence.” In those years Petliura edited the Kyivan newspaper Slovo [The Word], which exposed chauvinism and the antisemitic views of some writers published in the newspapers Rada [The Council] and Ridnyi krai [The Native Land].

It is impossible to ignore the immense popularity of traveling theaters, both Ukrainian and Jewish ones, which reached every remote corner. Incidentally, Jews in the shtetls kept Ukrainian theaters sold out. There was a constant cultural exchange: Ukrainian troupes reconstructed the world that was very familiar to Jews and the opposite.

This is happening to the present day. In my home town of Winnipeg, it gives me great pleasure to go to the Jewish cultural center, where old films in Yiddish are screened. You get the impression that you have landed in the Ukrainian world that speaks a different language. I think that Jews had the same impression when they attended Ukrainian shows; these were not hermetically sealed worlds. This is what makes Ukrainian culture, which includes Poles, and Russians, and Germans, interesting.

Plays that were written in 1920-1922 about how Jewish women fall in love with Ukrainians were a big discovery for me, for example. These plays were staged with great success in small towns throughout Canada, and this is a forgotten page of history.

Today, who remembers, for example, the choreographer Vasyl Avramenko, who created modern Ukrainian dance? He and his ensemble toured the world, and one of his favorite dances was the Jewish dance called the hora. He performed it everywhere, including in Madison Square Garden, where more than five hundred people came out on stage at the same time, and in 1970 in Jerusalem.

The first Jewish voice in Ukrainian literature is that of Hryts Kernerenko (Kerner). Was he one of ours among strangers; a stranger among his own people?

To a certain extent, yes, as he himself wrote in the poem “Not a Native Son”:

Farewell, my Ukraine—

I must abandon you:

Though I would give up

My life and freedom and soul!

But I am your stepson,

I know this well, unfortunately.

And among your other children

I do not live—I suffer.

I no longer have the strength to endure

Those jeers beyond measure

That your sons and I

Are not of the same faith.

You, my Ukraine,

I will love always:

Because you are my stepmother,

Still, you are a mother to me.

It was written in 1908, and it accurately conveys the sense of identity bifurcation. I grew up in a completely different epoch, in a Ukrainian-speaking family in Britain, but even I felt something similar, albeit to a much smaller degree. In Canada, where I live today, the policy of multiculturalism is officially established. But Kernerenko lived in absolutely different realities when special courage was required to choose a Ukrainian-Jewish identity. It was he who drew attention with his work to the fact that Ukrainians also exist, and this was a breakthrough in Ukrainian literature.

Kernerenko was published quite frequently in the pages of prestigious journals and in anthologies. For many people, it was important to hear this voice, to grasp what it means to be a Ukrainian—not by birth but by conscious cultural choice.

How was the failure of the Ukrainian-Jewish rapprochement during the UNR period reflected in journalism and fiction?

On the wave of a universal upswing, Jewish parties supported the Central Rada, and this was extremely important for the UNR because Ukrainians comprised no more than a third of the urban population. The other two-thirds were Russians and Jews in the east, and Poles and Jews in the west. This was what determined the UNR’s policy aimed at granting national and personal autonomy to minorities.

We all know what happened later; the pogroms of 1919 echoed in Ukrainian literature like a cry of pain. In 1919 (according to fragmentary evidence, allegedly at Petliura’s request), Stepan Vasylchenko writes the short story “Pro zhydka Marchyka, bidnoho kravchyka” [About Marchyk the Jew a Poor Tailor], which appeared in the newspaper Ukraina in the then capital of the UNR Kamianets-Podilsky, and was published in a separate edition. The plot is simple: A poor Jew, along with everyone else, welcomes the February Revolution, but a year later he perishes in a pogrom.

Klym Polishchuk also wrote about the pogroms. His short story “The Detour (From the Notebook of an Unknown Man)” is the diary of a Red Army Soldier, a former supporter of Ukrainian independence, who falls in battle. He is shocked by the brutality of war, especially when he discovers the body of Ida Goldberg, a famous actress who was killed during a pogrom.

By the irony of fate, the commanders of the Ukrainian and Bolshevik regiments know each other very well because they grew up together. Both believe that they are fighting for an independent Ukraine. But these two do not represent all of Ukraine. Describing the funeral of his favorite actress, the author notes that two Ukraines are fighting each other, and a third is lying before them in a grave.

Can one say that the policy of Ukrainization and indigenization in the 1920s made Ukrainians and Jews allies in the sphere of cultural construction?

In this context, Maik Yohansen’s books about Jewish colonies, which was written in 1929, is characteristic. He writes that wall newspapers appear in two languages: Yiddish and Ukrainian. During the winter the local theater staged six plays: two in Yiddish and four in Ukrainian. The younger generation, unlike their elders, is already communicating in Ukrainian. He writes about Jewish girls jumping around the steppe, about Jewish tillers of the soil, about soccer players playing for the Ukrainian national team, about a huge agronomist of intimidating appearance. Like the sketches of colonists that the artist Mark Epstein did in those years, Yohansen’s portraits bear witness to the fact that Jewish colonists differed little from their German or Ukrainian neighbors.

The future chairman of the Union of Writers of the Ukrainian SSR Yurii Smolych claimed that for many Jews in the 1920s Ukrainian became their native language. But can one speak about the emergence in these years of a pleiad of Jewish writers who made a name for themselves in Ukrainian literature?

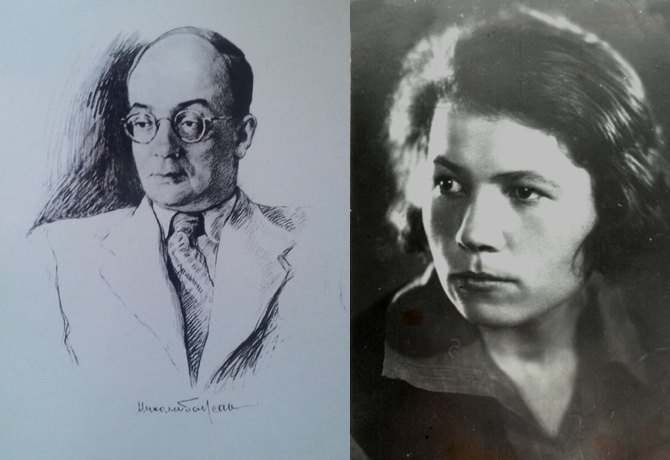

Most notably, there is Leonid Pervomaisky (Hurevych), a great Ukrainian writer, whose works, unfortunately, were disfigured by late editions, in which the Jewish G-d became “nature,” religion—“philosophy,” and a rabbi—“a good man.”

In the 1920s the Jewish voice was heard distinctly in the poetry of Raisa Troianker, in which nostalgia for her Jewish childhood is combined with blatant eroticism. At the age of thirteen, the young girl ran away from Uman with an Italian tiger tamer from a traveling circus. Later she fell in love with Volodymyr Sosiura and went to Kharkiv with him, where she published two collections.

Many Jews were literary critics and, unlike Kernerenko, they were no longer reproached for their origins. Before everyone’s eyes, a new urban, Ukrainian culture was being born, and Jews played some small part in this process.

On the other hand, Jewish figures begin to appear in the works of many Ukrainian writers: Mykola Khvylovy, Mykola Bazhan, Borys Antonenko-Davydovych, Yurii Smolych, and many others.

Moscow was alarmed by this wave of Ukrainization and indigenization. I have just published a book that analyzes the first works on the history of the Ukrainian Revolution written by Jews. Authors such as Moisei Ravych-Cherkasky, a proponent of Ukrainization, and Moisei Rafes, member of the Central Rada, criticize Russian chauvinism and the anti-Ukrainian sentiments of certain members of the CP(B)U; all of their articles on these questions were banned in 1926, destroyed, and forgotten.

Also repressed were Jewish scholars who had played an active role in Ukrainization, such as Olena Kurylo, one of the founders of the Institute of the Ukrainian Scientific Language at the All-Ukrainian Academy of Sciences; Samiilo Shchupak, editor of Literaturna hazeta [The Literary Gazette], and others.

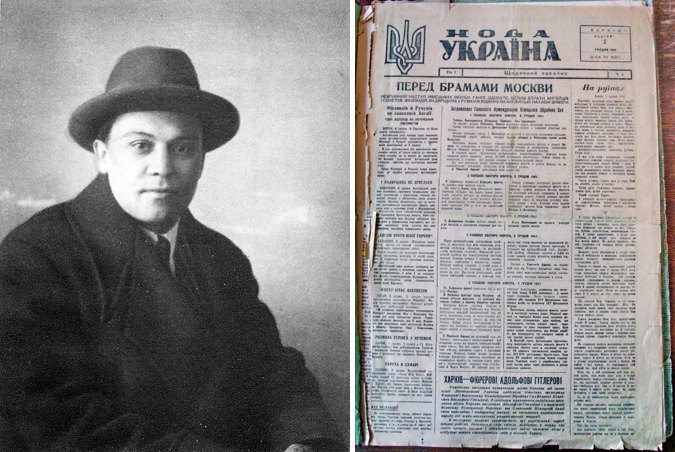

Nevertheless, antisemitic voices always existed in Ukrainian literature, and the voice of the talented prose writer Arkadii Liubchenko became one of the loudest…

There is a theory that Liubchenko’s antisemitism emerged in 1919 when he was supposedly betrayed to the Cheka by a Jewish tailor. In the 1930s, he resented the fact that 24 of the 60 writers (according to his tally) living in the prestigious Rolit building were of Jewish background. He denounced his sworn enemy, Natan Rybak, who, according to Liubchenko’s opinion, was manipulating [Oleksandr] Korniichuk, the head of the Union of Writers, and whose sister was Rybak’s wife.

According to some, other Ukrainian writers protested that their head was a Jew. We also know about the speech given by [Oleksandr] Dovzhenko at a meeting of the Union of Writers, who declared that “Jews have poisoned Ukrainian culture…they will always hate us, they seek to crawl in everywhere and take over everything.” And no one corrected the director.

As regards Liubchenko, his antisemitism was of a racist nature. It is no wonder that under the Germans he edited the Kharkiv newspaper Nova Ukraina [New Ukraine]. A particularly vivid impression is made by the pages of his diary with its description of a trainload of Hungarian Jews heading for a death camp: “Gray-haired, hook-nosed, with side-curls—I don’t feel sorry for them; for so many centuries they so cruelly tormented my people.”

He was absorbed in the cult of power that in the 1930s began to dominate both politics and, partly, literature. Liubchenko writes about beasts, about the nature of man, about the desire to see strength in his people—all this amplified his hatred of Jews, and he speaks about this openly.

Liubchenko admired the cult of power, and the majority of his fellow writers, both Ukrainians and Jews, followed another cult. Pervomaisky went from being a sentimental Jewish writer to a militant Stalinist, placing the power of his word at the service of the party.

There are certain indications that even Mykola Khvylovy served in the Cheka, and Pavlo Tychyna’s “Partiia vede” [The Party Leads] can serve as an example of the bloodthirsty rhetoric of the 1930s. But this is not an exclusively Nazi or Bolshevik phenomenon. [Ernest] Hemingway and [Rudyard] Kipling also paid tribute to this trend; Filippo Marinetti wrote that Italians should not eat pasta but more meat, in order to acquire a fighting spirit. Social Darwinism had swept the world. In order to survive, we must be forceful and strong; have nails, as Volodymyr Martynets, one of the OUN’s [Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists] ideologues, wrote.

But this period passed, and in the 1960s that same Pervomaisky wrote completely different poems as if atoning for his fascination with the cult of power.

Did the Jewish-Ukrainian writers’ wars in the late 1940s–early 1950s spoil relations between these fellow writers for a long time?

In 1947, when the offensive against “bourgeois nationalists” began, damning letters attacking Maksym Rylsky, Yurii Yanovsky, and Petro Panch were signed by such Jewish critics as Yevhen Adelheim and Illia Stebun (Katsnelson).

A few months passed, and Ukrainian writers “replied’ to their Jewish colleagues. Liubomyr Dmyterko lashed out at the critic Oleksandr Borshchahovsky, who at one time had written a scathing review of Oleksandr Korniichuk’s [play] Bohdan Khmelnytsky, and at Efim Martych (Finkelshtein) for his attacks on Kocherha’s [play] Yaroslav Mudry. Abram Hozenpud, Lazar Sanov (Smulson), and the above-mentioned Stebun and Adelheim were accused of desecrating the Ukrainian classical heritage.

In 1951 a new campaign unfolded to expose “Ukrainian bourgeois nationalists,” and “anti-Zionist” purges took place in 1952–1953. One year they cleaned out the Jews and then the Ukrainians. One drowned the other, and then the wheel turned in the other direction. People engage in villainy during periods of political paranoia; no spotless people remain.

How did Ukrainian writers react to the Holocaust?

First and foremost it must be remembered that the emphasis on the Jewish tragedy was not welcomed by the authorities. Nevertheless, back in 1943, Mykola Bazhan had paid tribute to the memory of Babyn Yar—eighteen years before [Yevgeny] Yevtushenko. In 1942 Tychyna wrote “To the Jewish People” and “The Jewish People,” and a year later Maksym Rylsky wrote his “To the Jewish People.” It is another thing that these poems did not reach the reader; Rylsky’s verses saw the light of day only in 1988.

Few people know about Dokia Humenna’s novel Khreshchatyi Yar [The Cross-shaped Ravine], based on a diary that she kept during the years of occupation. Conformism, the culpability of silent witnesses, and the reaction to ultimate horror are all questions that began to be discussed in society a decade later, but all of them are raised by Humenna. The novel came out in the West in the early 1950s. It had a broad resonance with the public, as this was the first attempt to comprehend the Holocaust and Ukrainian-Jewish relations in these years. [Anatoly] Kuznetsov’s Babi Yar was written ten years later. But the book was soon forgotten, and to this day it has not been published in Ukraine and is practically unknown.

It is telling that the writer does not idealize the abstract “people,” knowing full well what this simple people with its wonderful traditions are capable of. At the same time, Humenna’s view of Ukrainian identity was far ahead of its time. She sees as members of the great Ukrainian family all the peoples that left a trace in our history and culture, from the ancient Trypillians to contemporary Jews.

Did Jews find a “literary” place for themselves within the framework of the new Soviet Ukrainian patriotism?

A place was found for them in the distant future, but the context was changed: Jews became allies of Ukrainians and, generally, positive heroes. In Bazhan’s versified drama Oleksa Dovbush, a Jewish landlord and his daughter are the true friends and helpers of the noble brigand. In Yakiv Kachur’s novella “Ivan Bohun,” a Jew named Itsyk joins the Cossacks and fights artfully and valiantly. Ivan Le, in his historical novel Nalyvaiko, also introduced the image of a Jew who joins Severyn Nalyvaiko’s uprising.

The writer Pavlo Zahrebelny, in his novel Ia, Bohdan [I, Bohdan] broke the taboo on describing anti-Jewish violence when he broached the topic of the pogroms during the Khmelnytsky era.

This is an interesting example but not the only one. To what degree are contemporary Ukrainian writers ready to discuss not just the idyllic but tragic pages of their shared history?

For the moment, they’re not very ready because these topics are still not being discussed in society. But it is crucial to do this. For starters, at the very least that diary of Dokia Humenna’s should be published. Many people are still not aware of the problem of Ukrainian participation in the Holocaust, all the more so as sometimes this goes against some narratives of the OUN and the UPA.

Every incident should be examined individually; there were genuine heroes among UPA members. But we should not forget what some members of the OUN did in Galicia in 1941, or what members of the UPA did in Volyn in 1943. One and the same man could have been both a victim and a criminal. This is a very complex history, and no writer has appeared to recount this.

Meanwhile, a very interesting work, Sweet Darusia: A Tale of Two Villages, by Maria Matios, came out in 2000. The novel takes place in a Bukovynian village during the Second World War. This is an honest book, revealing the theme of the local population’s participation in violence and the appropriation of property during the latest change of power.

Generally, Ukraine is a very interesting country. You have problems there that are challenging historians, writers, and civic society. This forces you to reflect on complex questions, and there is no escaping this complexity.

Has a Jewish-Ukrainian identity emerged in contemporary Ukrainian literature, or is Moisei Fishbein a unique author in this respect?

Fishbein experienced an extremely successful fusion of identities. This is a Ukrainian poet whose fate it was to be born a Jew. His work concludes as it were, the discussion of the Ukrainian identity of Jewish writers, starting with Kernerenko, Troianker, and Pervomaisky. This evolution reflects the format of the perception of the Ukrainian Jew; first, as an “outsider,” then as one of “ours” but inconvenient, and, finally, a perfectly acceptable “one of ours.”

In recent years many civic activists, journalists, and others have begun to position themselves as Ukrainian Jews. This is important not just for Ukraine but also for the West, where people raise their eyebrows at the word combination “Ukrainian Jew.”

Since the Maidan, we have been living in a completely different epoch—an epoch marked by the birth of a new Ukraine and a new concept of Ukrainianness. You and I are sitting in downtown Kyiv in a Crimean Tatar restaurant, and this too is Ukraine, one of the variations of the new Ukrainian identity that is forming before our very eyes. The main thing today is not to interfere in its development.

Mikhail Gold,

Editor-in-chief of the newspaper Hadashot

Originally appeared in Russian @lb.ua

Translated from the Russian by Marta D. Olynyk.

Edited by Peter Bejger.