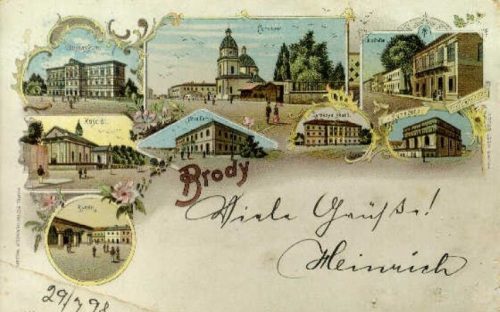

Nash Holos: Brody, Ukraine

The Western Ukrainian town of Brody is on my mind today. This historic town has always been in the minds of several generations of Jewish traders, writers, rabbis, and immigrants to the New World.

The Western Ukrainian town of Brody is on my mind today. This historic town has always been in the minds of several generations of Jewish traders, writers, rabbis, and immigrants to the New World.

Boris Kuzmany of the Institute of Slavonic Studies at the University of Vienna can tell us why this one particular town has retained a vitally important place in Ashkenazi Jewish memory.

His fascinating article in the journal East European Jewish Affairs, entitled “Brody Always On My Mind: The Mental Mapping of a Jewish City”, explores just how and why little Brody became a legend.

It all started with trade. Brody was always a lively center but the tempo really picked up in 1629, when a Polish noble bought the place. There was an influx of Jewish merchant families.

Jews were under the direct protection of the noble city owners and could live without any restrictions within the town and work in any profession or engage in commerce.

By the middle of the eighteenth-century Brody became the region’s most important hub for trans-European trade. It was the linchpin of trade between the German lands and points east into Ukraine and Russia.

An affluent mercantile elite funded the splendid architectural landmark of the Great Synagogue, a touchstone in the town’s physical and mental cityscape for more than two centuries.

After Poland disappeared in the late eighteenth century, Brody found itself on the border between the newly rising Austrian and Russian empires. The Austrians made it a free trade zone and business was booming.

Brody’s merchants developed close ties with Odessa. When that Black Sea city was declared a free port by the Russian tsar in 1803, many Jews from Galicia and Germany moved there. These newcomers to Odessa were called “Brody Jews” even though many were not originally from Brody. But those from Brody were the most prominent and they opened huge branch offices in Odessa. Therefore, Brody’s name and fame continued to spread to new horizons in the Jewish world.

Brody was not only a place for Jews to earn a living. It was also a place of Jewish learning. Scholars educated in Brody were renowned for their strict Jewish Orthodox traditions and their knowledge of the Kabbalah. Brody’s rabbis and judges were considered authorities.

Some Brody scholars made their way west, with one becoming Amsterdam’s chief rabbi in 1735 and another Prague’s chief rabbi after 1755.

And it worked the other way around. Brody’s merchants visiting the trade fairs in Germany brought back the ideas of the Jewish Enlightenment and were crucial in spreading new ways of thinking eastward.

Brody declined in importance in the late nineteenth century. But it retained one advantage that would continue to be of vital importance for the Jews of Eastern Europe -- the border.

Brody was the gateway to a kinder and gentler Western world for the flood of desperate Jews in the tsarist Russian Empire escaping pogroms, military service, or poverty.

The railroad via Brody was the shortest route for Jews in the Russian Empire to reach the big cities in Western Europe or ports to take them across the Atlantic to a new life.

The renowned Yiddish writer Sholem Aleichem emigrated from the Russian Empire via Brody in 1905. His [last and unfinished] novel Motl, the Cantor’s Son enshrines in fiction the experience of Jewish families streaming through the Brody doorway to the West, either legally or illegally. The Jewish novelist Joseph Roth, born in Brody in 1894, used in his fiction the inns at the border as those fateful places where Jews and Christians met to make their deals.

In 1914 the town of Brody was two-thirds Jewish. In 1945 only a few dozen survived the Holocaust. The old empires, and their borders were gone. New malignant forces had wiped out a centuries-old heritage. The synagogue today is in ruins.

But memory remains. And Boris Kuzmany, in his compelling historical outline, reminds us how this little Western Ukrainian town of Brody would be enshrined in Jewish memory and imagination.

This has been Ukrainian Jewish Heritage on Nash Holos Ukrainian Roots Radio. From San Francisco, I’m Peter Bejger. Until next time, shalom!

Listen to the program here.

Ukrainian Jewish Heritage is brought to you by the Ukrainian Jewish Encounter (UJE), a privately funded multinational organization whose goal is to promote mutual understanding between Ukrainians and Jews. Transcripts and audio files of this and earlier broadcasts of Ukrainian Jewish Heritage are available at the UJE website and the Nash Holos website.