Oleksandr Averbuch on poetry and the intercultural relations between Ukrainians and Jews

Originally appeared in Ukrainian @chytomo.com

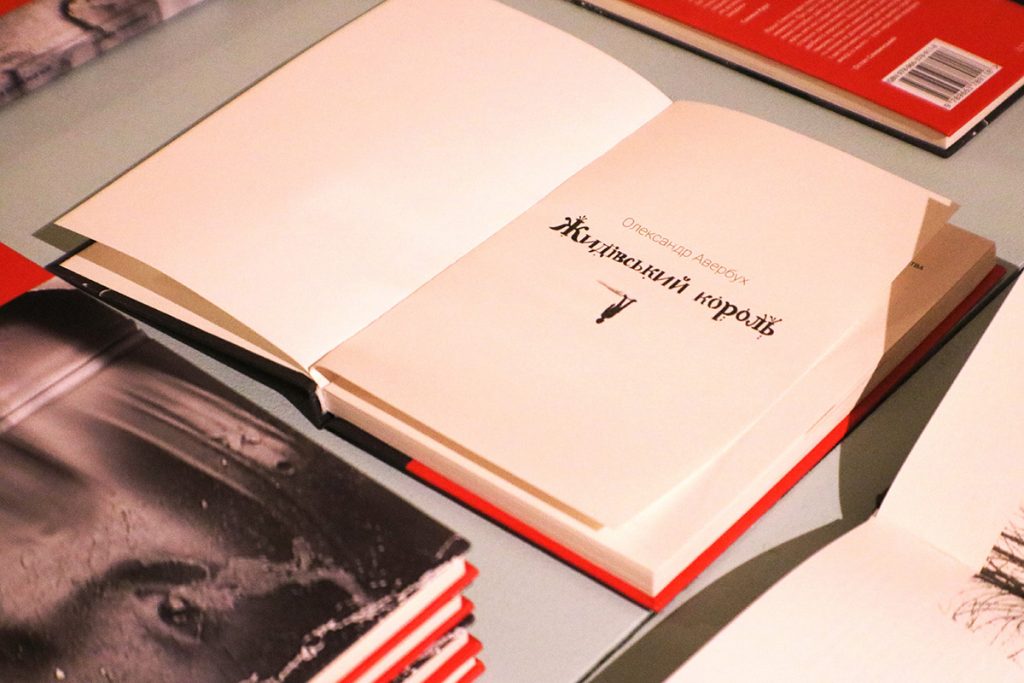

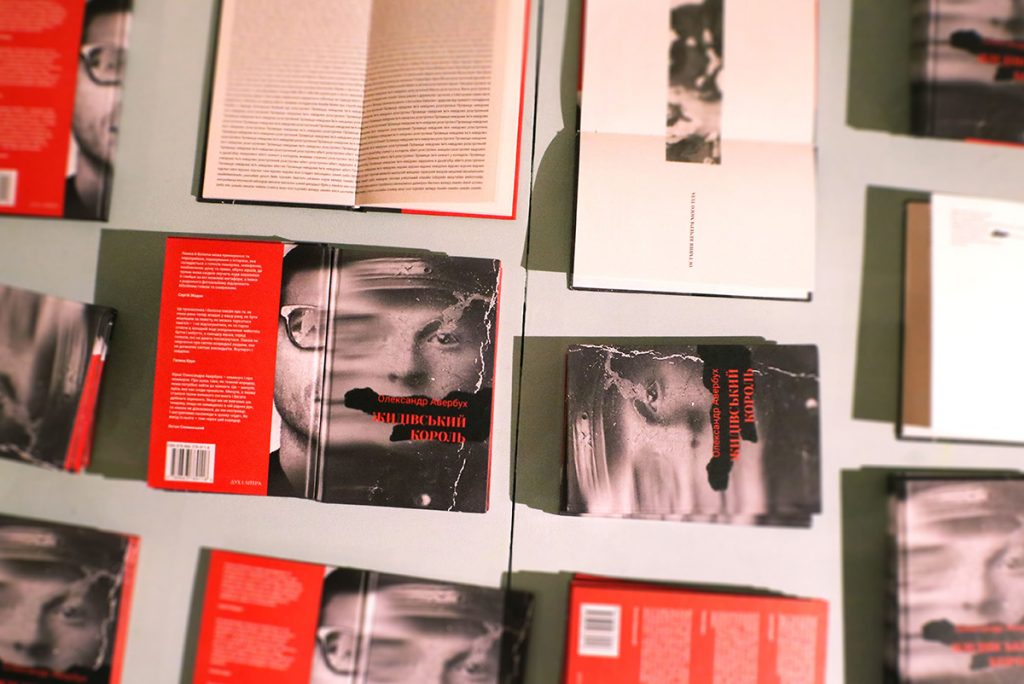

(Editor's note: Ukrainian Jewish Encounter supported the publication of Oleksandr Averbuch's poetry collection "Zhydivskyi korol" [The Jewish King].)

During the first three months of the war, the recontextualization of historical experience became one of the most dynamic discourses in contemporary Ukrainian society, which is reassessing and examining itself and others, and seeking difficult answers to difficult questions. The writer, poet, and literary scholar Oksana Lutsyshyna and the poet Oleksandr Averbuch discuss Ukrainian-Jewish literature and Ukrainian Jewry, centuries of neighborship, cultural exchanges, and mutual enrichment, as well as the poetry collection Zhydivskyi korol [The Jewish King], which, as Serhii Zhadan noted, is relevant today because, among other things, it "consists of voices of the dead, the desperate, those deprived of home and disenfranchised … where the direct speech of eyewitnesses sounds much clearer and deeper than any possible metaphors."

Sashko, your collection appeared on the eve of Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Some copies that the publishing house sent out never reached their addressees. The collection became "suspended" somewhere in the space of wartime and redrawn geography. What significance does this have for you?

I perceive my texts as a "part" of my body. And right now, quite symbolic events are happening in connection with this "part." For example, my collection was in transit from Kyiv to Lviv for three months. It arrived in Kharkiv together with humanitarian aid, but once it approached Kherson, it was returned [as no post services were available]. I tracked the collection as it was in transit, and when it approached Kherson, the tracking stopped for a few weeks, as though hesitating between entering and retreating, and then the delivery came back.

When my collection is "traveling" this way somewhere in Ukraine, when I imagine that it might end up in the occupied territories, I almost feel as though I am being torn to pieces. It can be said that my internal geography has also been completely redrawn.

Your book is largely based on letters that you found in archives. When I first heard about it, I was amazed. Here you have syntax and apparent simplicity that imitates the style of a literate person but one who is far from being "bookish," and generally life itself, often terrible, in wartime or postwar, wafts from them [the letters]. Right now, our communication has changed dramatically. Our descendants may not even have any letters from us left, just conversations on Zoom recorded somewhere on the tablets of the noosphere. Why did you decide to continue the book in the epistolary format? What does this format offer us as readers?

The letters of Ostarbeiters and Jews, who were searching for their relatives in villages after the Second World War, were a revelation for me. For Ukrainians who had been forced to work in Germany, this was the only way to hold onto the past, to remember and note down in travelogue letters what was happening. Correspondence is generally a rather ambiguous genre, somewhere in between documented materials and literature. There is the idea that a letter is always addressed to a larger audience than is indicated in the address line. The Ostarbeiters wrote about their feelings to their loved ones, their fellow villagers, and the military censor, the latter crossing out everything that was disturbing.

I stylized each letter or collected fragments of various letters. For me, correspondence as the core of my collection has a dual sense: to reveal human pain and to offer a new type of candor that counts on public attention.

Today quite a few projects are collecting the testimonies of Ukrainians about Russia's invasion. These people, too, want to be heard. I have a poem that ends with the line: "The only thing that we want right now is for our pain to be acknowledged." This is about the impossibility of remaining silent, about the thirst to publicize the horrors, and counting on understanding.

The letters in the collection resonate with what is happening in my native Luhansk region. Today I have barely any contact with my relatives and friends; I have been waiting for some word for weeks. And you know, the reports received are reminiscent of Ostarbeiter letters written in coded language that is frightened and humiliated and which seeks new ways of expression. Its nearly telegraphic restraint alarms and causes pain. The occupation is bringing suffering not just to people; it is also taking language prisoner, which shrinks in fear but, for the sake of survival, seeks an exit on creative levels.

One of the first poems in your book is a shocking text about how the lyrical hero "who forgave himself/a Ukrainian great-grandfather who took part in a pogrom against a Jewish great-grandfather/forgave a Polish great-grandmother, who tore the braids of a Jewish great-grandmother." Through this family history, I see an authentic palimpsest, a kind of book of life, ramified and unexpected, but also a certain suggestion of a literary phenomenon that we call Jewish literature. This literature is created on various continents, in various countries, in various languages. Writers write in Hebrew or Yiddish, for example, but they are Poles and Ukrainians and Americans. Writing, as a body in your poem, becomes a sort of Eucharist. How do you see yourself in this diverse and complex context or landscape? Do you position yourself as a Jewish or a Ukrainian poet, or do you believe that your writing identification simultaneously includes both one and the other? Are there, perhaps, some elements that I haven't named?

I perceive myself as a Jewish-Ukrainian poet. The poem that you are talking about is not only a contemplation on the multiethnic hodgepodge in my veins or the struggle of identities. It is also about the fluidity of the "indestructible" categories of an ethnic group, a nation, heritage, involvement, and our unwillingness to undermine these concepts. And the question of involvement is key here because history today demands clarity. For me, this poem has a double meaning. It is about guilt and forgiving our ancestors for crimes that they once perpetrated against each other; about reconciliation through death and giving yourself completely to those who gave birth to you, and at the same time, about the barbaric shredding of the diverse whole by those seeking to grab the biggest piece, seeing "one's own" in it.

The motif of the Eucharist, which is traditionally treated as the unification and reconciliation through the body and blood, through grief and longing, betrays itself, becoming a motif of sacrifice that is supposed to "feed" the gaping, hungry maw of history and, finally, to calm it down. Thus, if one understands Jewish literature as a phenomenon that emerges out of the clash of feelings of all-involvement and orphanhood, shelter and homelessness, anger and guilt, omnipotence and helplessness, dissolving in one and recoiling from another, then what I am engaged in is Jewish literature.

Jewish culture is thousands of years old. The temptation even arises to call it eternal because it dates back to the depths of human civilizational memory. Tell us how tradition, the Bible, and the Torah are inscribed in your work? What do they mean to you? Are they echoed in your writings?

Both the Jewish and Christian cultures are important to me. I know by heart countless prayers both in Church Slavonic and Ancient Hebrew. Poetry and prayer are close in terms of genre. Prayer is also a kind of "letter," a message from different people to the same addressee, who are not certain of a response, like the Ostarbeiter.

Poetry (like prayer) is crucially necessary in wartime. People pray, but they also write poems because this provides a feeling of hope that someone will hear them. That is precisely why, during a war, there is always such a blaze of poetic creativity. I do not endorse Adorno's famous statement about the impossibility and inappropriateness of writing poems after the Holocaust. Poetry during wartime is both a panakhyda [memorial service] and a need to express oneself. It is both appropriate and timely.

You lived for a time in Israel. What formed this experience in you as a person and as a writer?

I lived in Israel for 15 years. After seven years in Canada, I still feel like an Israeli. It is much easier for me to communicate in Hebrew than in English, and sometimes in Ukrainian or Russian. For a few years, I worked hard on my Hebrew pronunciation in order to rid myself of my accent, but I didn't succeed. In general, imitating habits, dialects, and accents is what appeals to me in life and in poetry. Maybe that's why I write documentary poetry, because I am very attracted to the voices of others, intonations, even mistakes.

In Israel, I was very much influenced by my military service. I was not part of the combat troops, but during my service, the Second Lebanese War broke out. I worked at a center for the coordination of the population, where people called in to find out what was happening. Mostly these were elderly people as well as those who did not know the language and could not monitor the news. There was a woman from the city of Safed, Mira Mykhailivna. She lived alone, she was very frightened, she didn't understand what was happening. Sometimes my colleagues would wake me up to talk to her, even though it was not my shift. She refused to talk to anyone else. It was during those three years in the army that I wrote my first poetry collection. In general, Israel influenced me on the level of ideas, motifs, and worldview, but not forms. I never wrote in Hebrew.

Do you keep abreast of Israeli literature? Which of its features or themes strike you as definitive?

In the early 2010s, I worked as an observer of Hebrew literature. Israeli literature is not just Hebrew and not just Jewish. There is literature in Arabic and Russian; I saw some things in French. Arabic (non-Jewish) literature that, on the whole, is practically unknown to the general Hebrew-speaking reader. But Israeli Jewish literature is multilingual, because many Israeli writers are natives of various countries. I am very attracted to this "Babylonian" diversity.

What Jewish émigrés from Arab countries are writing differs considerably from what the Ashkenazi are writing. This was particularly felt during the first decades of the country's existence. During this period, the official ideology was aimed at forgetting the past and the diaspora, and at building something shared — something Israeli. So, this diversity was repressed. The literature of the 1920s–1940s is very engaged, a kind of socialist realism that was felt in the motifs, optimistic mood, and the idea of creating a new person, a new, secular Jew who has nothing in common with the weak, diasporic, feminine Jew.

Later there began a period of reassessing the past. The repression of Sephardi Jews from Arab countries, who were considered "incapable" of creativity, politics, and culture, rose to the surface. Not only novels and poetry collections by Sephardim began to appear, but also entire literary groupings, journals, and publishing houses. This intransigence and this unwillingness to forget oneself, these are among the defining features of Jewish literature that is being created in various languages, including Ukrainian.

Mikołaj Grynberg's book I Accuse Auschwitz: Family Tales, translated [into Ukrainian] by Oleksandr Boichenko, has just been published. These are oral testimonies of children of Nazi concentration camp survivors. I was particularly struck by one fact: After the war, Jews from Eastern Europe immigrated to Israel and were given a rather cool reception there because victim status did not seem worthy to Israeli Jews. They would have preferred to see resistance. This attitude changed only after the Eichmann trial in the 1960s. It was only then that people began to comprehend what the concentration camps actually were, how they broke people and took away their will to resist. This book attests once again that the unique experience of Jewish existence can be very different in various historical contexts. Did you experience culture shock when you were living in Israel? Were there things that your environment didn't understand about you, despite common roots and perfect fluency in the language?

I arrived at a kibbutz in Israel alone, without family, from a large village in the Luhansk region. It was a commune with shared property, obligations, shared clothing and laundry, dining room, and holidays. For me, this was a move from a village to a collective farm with cows, chickens, and fields — everything to which I was accustomed. When I read Israeli works dating to the beginning of the state's founding, I saw in them only my own village in the Luhansk region, with its hay, cattle, and rivers. Our kibbutz was next to the Jordan River, while Novoaidar is situated on the Aidar River.

The experience that you are asking me about belonged to the older generation of emigrants. My landlady in Tel Aviv, who was from Poland, arrived in the 1950s. She recounted how they were accused of passive non-resistance to the Nazis, of going to the gas chambers like "sheep to the slaughter." The use of Yiddish at that time began to be considered "shameful" because this language was associated with the "failure" of Ashkenazi Jews, an inability to defend themselves. This was contrasted with Hebrew and the new Jew/kibbutznik, the creator of his fate, state, and future.

Contemplating this, I imagine the people who remained in the occupied territories. Sometimes to some people, they appear as traitors, a "population not worth fighting for." But when I communicate with family members and friends from there, I understand that they are living in captivity — in fact, in concentration camps — and that they may be destroyed any minute.

Another of your poems that made me think a lot is about returning; "how to return to a city that does not exist / how to return to a home / if it is gone, like heavy grief / renamed streets / like swollen blood vessels / do not find the confluence." It is about banishment, exile. It is my understanding that your departure from Ukraine to Israel was, rather, the beginning of your journey and not all its conclusion. What is your notion of home and return in poetry?

Banishment, which you mention, is connected with the "temporariness" of the Jewish presence in Ukraine (and not just in Ukraine). It also conditions the attitude to Jewish-Ukrainian literature as something external, incomprehensible, alien — but present. That is why Jews and the Jewish heritage are perceived, especially in the last decades, as part of Ukraine's past but not as part of the present.

What does this cautious, practically inclusive attitude indicate? Probably, contradictory feelings. Even these days, when Jews are evacuating their own people, when Jews are hiding in synagogues, and Jewish organizations are helping to transport them to Israel, this stands out against the backdrop of the general evacuation. I don't condemn this, no. People have to save themselves in whatever way they can. It's only that once again, I am seeing a clash between rootedness and temporariness, banishment.

This is a very difficult topic for me, really. I am troubled by the questions of involvement and presence in the places that are dear to me. The medieval Jewish poet Yehuda Halevi has this poem: "My heart is in the east, / And I in the uttermost west." He lived in the lands of contemporary Spain, but his longing for Eretz Yisrael never faded throughout his life. That is why, if we talk about the sense and notion of home as something safe and eternal, that does not exist in my work. My home is my memory.

I wrote the poem that you asked me about during a trip to Novoaidar in 2019. When I arrived in my village, where I had not been since 2002, I was confused by the renamed streets. The feeling of being lost was considerable.

How does one make sense of oneself as a Jew in the context of Ukrainian history and the history of literature? The Holocaust theme cannot be omitted here. In recent years several iconic books have been published: the poetry of Boris Khersonsky, Marianna Kiyanovska's collection Babyn Yar. Holosamy (The Voices of Babyn Yar), Vasyl Makhno's novel Vichnyi kalendar (Eternal Calendar), and Sofia Andrukhovych's [novel] Amadoka. I have deliberately mentioned only comparatively recent publications. What problems do you see in dealing with this theme? In literature, have we come at least close to the story of the Holocaust, or are we just feeling our way?

I am part of Ukrainian literature, but I will never be "one of ours." Some component of me, mostly the Israeli one, is completely unfamiliar to this environment. Moisei Fishbein once wrote that he was born a Jew but was supposed to have been born a Ukrainian. I do not seek to get rid of my Jewishness, and I don't want to be an exotic flower in the front garden of Ukrainian literature. European literatures and, even more so, post-Soviet literatures, are ethnocentric for the most part (the consequences of centuries of colonialism). This is normal for cultures that are building themselves and seeking self-understanding.

The above-mentioned texts touch on the topic of Jews in Ukraine as something exotic, nostalgia for a multicultural past long gone. They romanticize it; this is an idyll of unity — a very positive view of history. And this is good for constructing a new Ukrainianness. But to this day, some works continue to rely on stereotypical depictions of Jews as middlemen and tavern keepers who live in Ukraine as foreigners, and the only thing that binds them to this land is the thirst for profit. I am not certain whether this literature is reinterpreting the image of the Jew from the perspective of the twenty-first century.

The Holocaust must be discussed in the form of a joint Jewish-Ukrainian dialogue. If we are talking about whether we have come close to the issue of the Holocaust in Ukraine, I think that with this war, we most certainly have. It is not just teaching us historical facts, but also providing context and a set of instruments — historical, artistic, literary, and linguistic — for how to perceive what is happening.

This is precisely why I am amazed by what Kiyanovska did with her poetry collection, because this collection expresses the capacity, the readiness to feel someone else's pain, to become the people who perished. For history, with its tragedies and horrors, is repeating itself because the Russian aggressor is destroying Ukraine's civilian population, along with those last few people who miraculously survived the Holocaust

Oksana Lutsyshyna

Translated from the Ukrainian by Marta D. Olynyk.

Chytomo: Ukrainian and Israeli authors held a poetry evening in support of Ukraine (In Ukrainian)