Olena Stiazhkina: "We are speaking about modern times only with words with which we had described the past"

[Editor’s note: LB.UA, one of Ukraine’s leading publications, ran a series of interviews with jury members for the 2023 "Encounter: The Ukrainian-Jewish Literary Prize" ™ before the prize winner was announced on 18 September 2023. The interview with jury member Olena Stiazhkina appeared in Ukrainian on 15 September 2023.]

Originally appeared in Ukrainian @lb.ua

This winner of Encounter: The Ukrainian-Jewish Literary Prize, whose goal is to comprehend the shared historical experience of Ukrainians and Jews, reach an understanding, and engage in dialogue between these two peoples, will be announced this week. This is the third year that the prize has been awarded. In 2020, the winning novel was Vasyl Makhno's Eternal Calendar, and in 2021, the prize was awarded to the Ukrainian translation of Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern's book The Anti-Imperial Choice: The Making of the Ukrainian Jew. In 2022, no prize was awarded because of Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

The 2023 winner of the Encounter literary prize will be chosen from the short list by a jury whose members include the philosopher and researcher Olha Mukha; the translator, publisher, and journalist Oksana Forostyna; and the historian and writer Olena Stiazhkina. We spoke with each of them about literature during the war and the role of the prize. In this second part of our conversation with Olena Stiazhkina, the writer reflects on how stories from the Second World War remain key to this day and offer us strength.

By Marta Konyk

What is your impression of the longlisted books?

I am a happy reader. It is a dream come true to read good books. Someone once told me that heaven is a lot of books and coffee. In my case, it is not coffee but tea, but the idea of heaven is the same. Being able to be with books in wartime conditions is happiness, a comfort, an opportunity to live a different life and to realize that, one way or another, we will win. The tragedies will remain with us, but since other people have shown us that this is achievable, we will be able not to experience tragedy, not live with it, as with a friend, but have it within ourselves and continue living.

In one interview, you said that the history of the Second World War is the history of modern times. Unlike in previous years, this year's short list contains books that are essentially about the Second World War. Why did it happen this way?

We did not choose the criterion of war as a way of forming the short list. Of course, this was our response, feeling, and contemporary reading of books that were published not so long ago and which were dedicated to the Second World War. There were no differences among us with regard to compiling the short list. To be honest, I didn't think about this. You have shown me that the Second World War lingers even in the very fact that we chose this list. I will think about this.

For us, the Second World War has not ended, just as it has not ended for those countries that were called by the vile word "post-Soviet." It was a shame to use this word to describe national, independent states. Western researchers often used it in narratives; I, too used it, and I regret this today. Fortunately, I have not written very much about international events. I understand that we are living in this war, and until it is brought to an end, we will not be able to be free and independent; no nation and no people could.

Today, a bacchanal is unfolding around the names of leaders; so-called good and bad Russians are laughing at someone who is a Сrimean Tatar or a Jew. We see that Russia is an absolutely genocidal civilization. These are people who can exist only when they are destroying others.

So, as regards the prize, the war, and the short list around the Second World War, we must note that the Second World War remains a key experience for us while we are fighting and until we triumph.

Is it true that Zelensky's Jewish roots also influence the view of us as a democratic country?

I am following the narratives from the Z country. The fact that they are allowing themselves [to say terrible things] about Jews in general and Zelensky in particular…. They never separate Zelensky from Jewishness; they use bad words about him, they demonstrate their savagery.

If Western analysts are tracking Russian narratives as scrupulously as I am, I think they have substantial evidence of the kind of evil that Ukraine has encountered during the war. Because today their narratives differ little from the narratives of Nazi Germany vis-à-vis the Jews.

How has the attitude to literature about the Second World War changed after 24 February?

Among a certain number of Ukrainians, a lot changed back in 2014. I am one of those citizens who thinks about the military narrative of 2014, along with other residents of Donetsk and Luhansk, Crimean Tatars, as well as a powerful number of fighters who stood up for Ukraine from the moment of the invasion, for which the term "hybrid war" was later found. In what sense was it hybrid is a different question.

Since then, it has become obvious to a significant number of people who love books that we had failed to understand everything; we had not finished reading, we had not finished writing about the Second World War experience. About its experiences, about the Nazi and Soviet occupations, about torture, about the bystanders present at executions who did nothing…. But also about saviors, Righteous Among the Nations, Soviet policies on Ukraine. In other words, there is a huge number of questions that, as Timothy Snyder has aptly written, were key for this war. However, to the average Ukrainian reader, they remained unimportant.

Here is a truly fine justification. No one in the twenty-first century should have thought that people could be killed this way, simply like this: because I can, because I feel like it, so that you Ukrainians will not exist. No one ever thought that you can ride tanks over dwellings and toss grenades at civilians in cellars. In this sense, our resting on clouds was justified more or less, although a lot of people were saying that we were next. Oksana Zabuzhko, for example, said this right after what happened to Georgia.

We saw tanks on our own streets. The first thing that comes to mind is to find similarities in history, in order to protect and console ourselves so as not to be afraid and to gain experience. Here, everything is absolutely understandable. The only thing that was similar for us in this story was the Second World War. And when we looked back, it turned out that we had moved forward, that we are speaking about modern times only with words with which we had described the past.

The literature about the Second World War turned out to be a pivot of understanding many processes, particularly the destruction of the myths that Kremlin propaganda had dumped on us — myths about what we Ukrainians were like in the Second World War.

Reading right now is a luxury. Sometimes you don't have the energy but, strange as it may seem, the circle of my colleagues and friends says that the books which are the easiest to read now — fiction or monographs — are about the Second World War. They have something in them that offers strength, hope, understanding, and mechanisms of movement. They allow us not to coagulate in the gluten of the Kremlin war myth. On the contrary, they help us to leave the established, cemented, and petrified narrative of the "Great Patriotic War."

When you were reading the longlisted books, how did they resonate with modernity?

Those books resonated with modernity when they came out in print. At the time of the award selection, I had only read two books from this list. I won't say which ones, so as not to evaluate them, because I'm the bad one, I wasn't able to deal with them. Before the full-scale invasion, my antenna was already a military one aimed at understanding, reinterpreting, an attempt to enroot myself in the correct perception of the Second World War. These books, like a crystal ball, revealed a new set of optics to me; they helped me to think more and, I hope, to gain a greater understanding of one of the most complex questions of the Second World War: Ukrainian-Jewish relations.

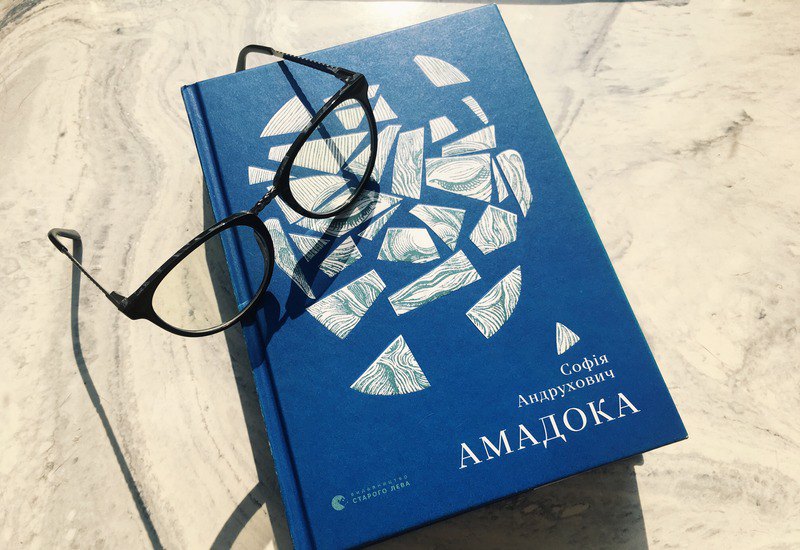

The more I read, the more I realized that I will return to those books because they contain not just optics but also beautiful words, words that you can lay gently on a wound. That's how powerfully formulated they are. Sofia Andrukhovych's Amadoka tells the story of Vasyl, who rescued everyone, and it was said about him that he saved many. Some people, though, believed that he had saved the wrong ones. He could have been handed over to the authorities, but the authorities changed so frequently that they didn't have time to hand over that Vasyl. Later, the author writes: "And there was another important question: What for?"

This is a phrase that I carry with me. We can often figure out the origins of evil, despite everything; it is quite cynically clear why people act badly. But when we try and figure out "What for?" in relation to what is good, we come up against…say, the word "miracle," say, the phrase "no explanations" or "because this is a person," or "because this is the way it's supposed to be." The pragmatism of goodness in catastrophic conditions is very much at issue here. Then, on the whole, being good and wonderful generally stops being pragmatic because, as a rule, this means bringing trouble on yourself. But why did Vasyl save people?

When I experience complicated moments, when I am very sad, when things happen that I don't want, when I find out about people who did bad things, then I think about this "he saved, what for?" There is no answer to this other than it is because you are a person, and this explains everything. So, these books are important in the context of thinking and feeling.

During wartime, the question of granting Andrei Sheptytsky the title of Righteous Among the Nations has understandably disappeared from the media space. Will we be able to return to it after victory?

We must do this despite everything — and always. I deal in particular with the history of the occupation during the Second World War, and I know that there are many more names than we can imagine which should be entered into the list of Righteous Among the Nations. We can't even include all the names because the very people who saved Jews died as well. Or they kept this a secret for so long that they went out into this world of books and a lot of coffee with their goodness, without even having asked for any support or recognition. And they are there right now.

We will definitely list those whose names we know, especially Andrei Sheptytsky. However, it is bitter for me to think about the huge number of people who did the same thing, and we don't know about them. We know there was Auntie Zina, there was Uncle Petro… and that's it; it is a legend, a myth, but Jews were saved. Later, the saviors dispersed, or they were murdered or taken away, or wherever they are, and we don't even have their names.

You know, the Unknown Soldier is a bad idea. Our Righteous Among the Nations are often left in that very same context as unknown soldiers. Let there simply be an Auntie Zina [as a Righteous Among the Nations]; this is a very correct, good, and honest matter that should be developed right now because this is, in fact, what we are also fighting for.

How have Ukrainian-Jewish relations changed in Ukraine after 24 February?

This is not a question for a Ukrainian audience. I have a wonderful colleague of my age, with whom I have not worked, but we run into each other at conferences. Professor Maksym Gon has researched the Holocaust in the Rivne region. I read an interview in which he recounts how, at the beginning of the invasion, he realized that all questions and scholarly works have become very insignificant; the only issue is what you can do at the front. That is why he went to the front.

I think that the only thing that we can say right now, as we are talking about Ukraine and Ukrainians, is that we are talking not about interethnic relations but about the relationship of political Ukrainians, Jews, Tatars, Poles, and Belarusians with that inhumane Russian civilization that is waging war against us. We are talking not about something inside ourselves because today, we are so different yet so united in the understanding that we shall be triumphant together. Otherwise, we shall all perish together.

Why do we like living together?

We have long-standing, personal stories of love. I also think that all Ukrainians and all Jews who are living in Ukraine today have such long-lasting stories of love; not romantic love but love. Friendly relations, familial, neighborly, and professional ones. The history of love is definitely crystallized in them.

My stepfather's father was Jewish; his name was Pavlo Solomonovych. He was a marvellous cook. I remember going to his house, and he always fed us children: whatever we wanted, however we wanted, as much as we wanted. From time to time, some unusual pastry would appear on his table: kruchenyky with raisins and nuts; we would call them rohalyky, crescents. Later, after his death, I read that this was a special festive pastry called rugelach. Rohalyky — rugelach — are specially baked on Jewish holidays. He never said that it was a holiday at the time. Children, come! Moreover, we had an international family, a huge number of second marriages and children from all the marriages.

I understand that, together with the unbelievably tasty pastry, all of this, this huge international circle of children of various ages was joining something very important and intimate for him. He shared this love with us. And I was supposed to learn, and I did learn how to make this pastry. I bake it not only on Jewish but also on Ukrainian holidays.

Ukrainian Jewish Encounter is an organization that is popularizing the following slogan about the Ukrainian and Jewish peoples: "Our stories are incomplete without each other." How did the shortlisted books manage to substantiate this idea?

Our female authors and one male author definitely did not try to conform to this slogan. They wrote these stories that we were able to read as such. To see them as integral, inseparable, the kinds where we have sprouted into each other. So, the responsibility lies with us, the jury, not with the authors, if something is not right. But, truly, our history cannot be read in discontinuity.

However, our Z enemies have constantly tried to do this very thing: to get us to hate each other. So that we would read one another not because we ourselves are doing the writing and what we ourselves are feeling, but because of what we are being sent from Moscow.

So, these books are important in the context of germination, of the impossibility of one without the other. They are important in that this is our view of our people who right now are looking at their past, one with delight, another with amazement, another with a certain detachment, another with mild sorrow. But definitely with our absolutely different optics with regard to the understanding of how we had been together, how much this was problematically good/bad. The 'Encounter’ literary prize has a significant advantage over other awards because who, besides us, can recount who we are? It is a strong word, where we talk about who we are in these relations.

Marta Konyk, journalist

Translated from the Ukrainian by Marta D. Olynyk