Olga Radchenko: "Jewish refugees had much higher chances to survive in the Soviet rear than in German-occupied territories"

Our conversation with the Ukrainian historian Olga Radchenko centers on her latest Ukrainian-language book, Jewish Refugees in Ukraine, 1939–1941. We discuss the number of Jewish refugees, where they hailed from, and how many of them were repressed by the NKVD. We also look at the subsequent fate of the survivors and how they persevered throughout the Nazi and Soviet occupations.

"I worked on this book amid the war that made the refugee question particularly prominent"

You recently published Jewish Refugees in Ukraine, 1939–1941. When did you come up with the idea for this book, and what compelled you to write it?

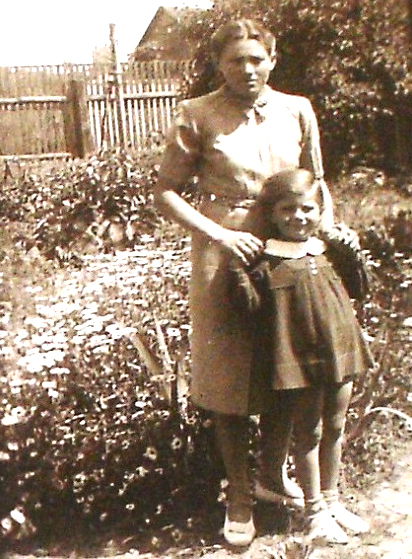

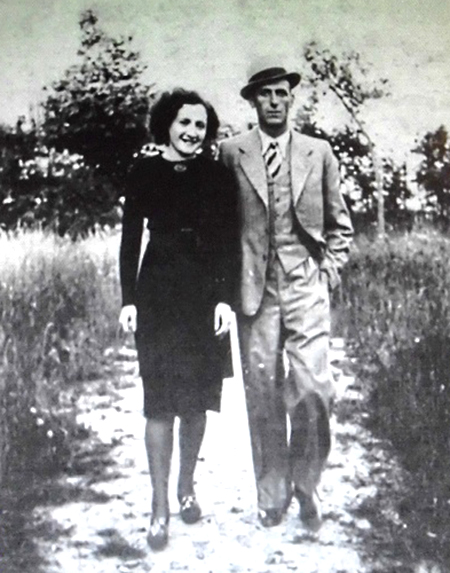

I began approaching this topic eight years ago during a conference held at the State Archive of Kirovohrad Oblast (DAKO) to which I had been invited. At the time, I was working on some archival criminal files on individuals repressed by the NKVD. In one of them, I discovered a considerable number of private letters and photographs of the German-occupied city of Tomaszów Mazowiecki, which a young woman named Estera Igielnik sent to her husband, Szymon, throughout 1940 and the first half of 1941. In October 1939, Szymon, together with his brother, left behind their relatives in central Poland and crossed the demarcation line separating the German and Soviet zones of occupied Poland. Szymon settled down in Kirovohrad, where he found a job. He obtained a Soviet passport and went through official channels to invite his wife and little daughter, Marylia, but in early 1941, he and his brother were wrongfully arrested by the NKVD and convicted. Estera and Marylia died in the Tomaszów Mazowiecki ghetto. The tragic story of this family struck me and led me to study the fate of European refugees in Ukraine during the initial phase of the Second World War. Two years later, I published the first short book on this topic, co-written with Viktor Bilous, DAKO's leading scholarly associate at the time.

I did not rest on my laurels and expanded the geographic scope of my scholarly pursuits. I turned the material I had collected into a number of articles published in Austria, Germany, and Ukraine. I am grateful to Leonid Finberg, editor-in-chief of the Dukh i Litera publishing house, who suggested I write a book about Jewish refugees. Our conversation took place in early February 2022, shortly before the Russian Federation's full-scale military aggression against Ukraine. Naturally, I worked on this book amid the war that made the refugee question particularly prominent. By the way, 2024 marks the 85th anniversary of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact and the start of the Second World War. Today, we have a better understanding of changed attitudes toward refugees and of the positive role that contemporary democracies play in organizing relief for people fleeing wars. However, regretfully, we have still not learned how to prevent full-scale wars.

From which regions did Jewish refugees escape to the territory of Ukraine in autumn 1939–winter 1940?

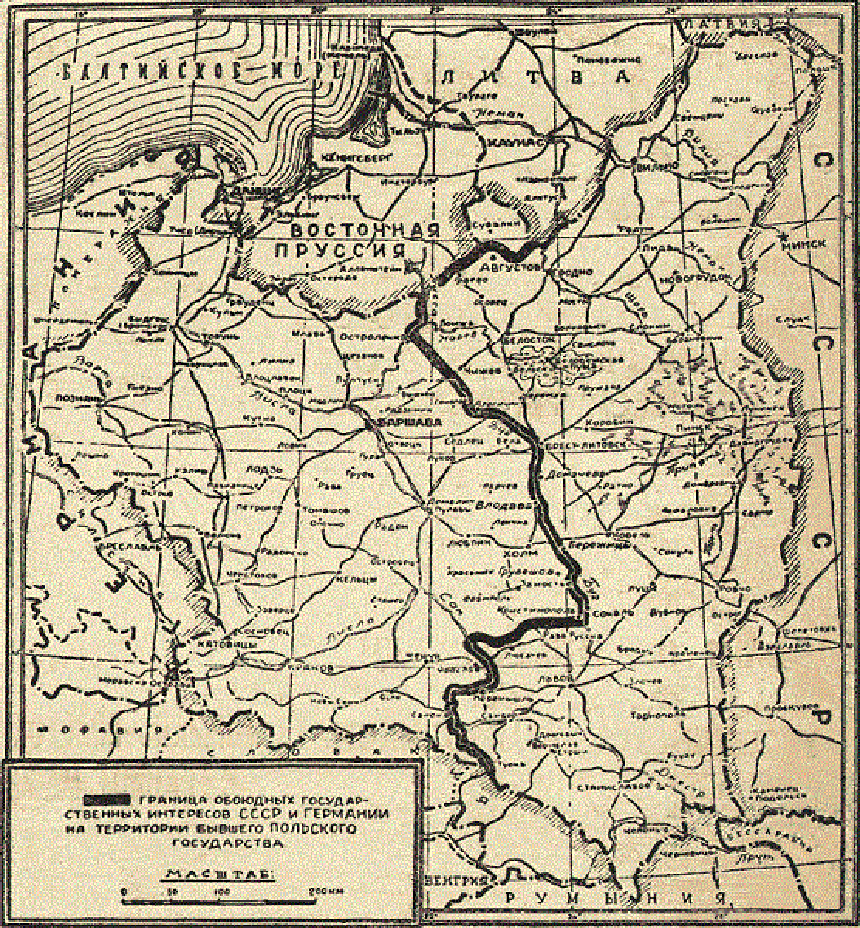

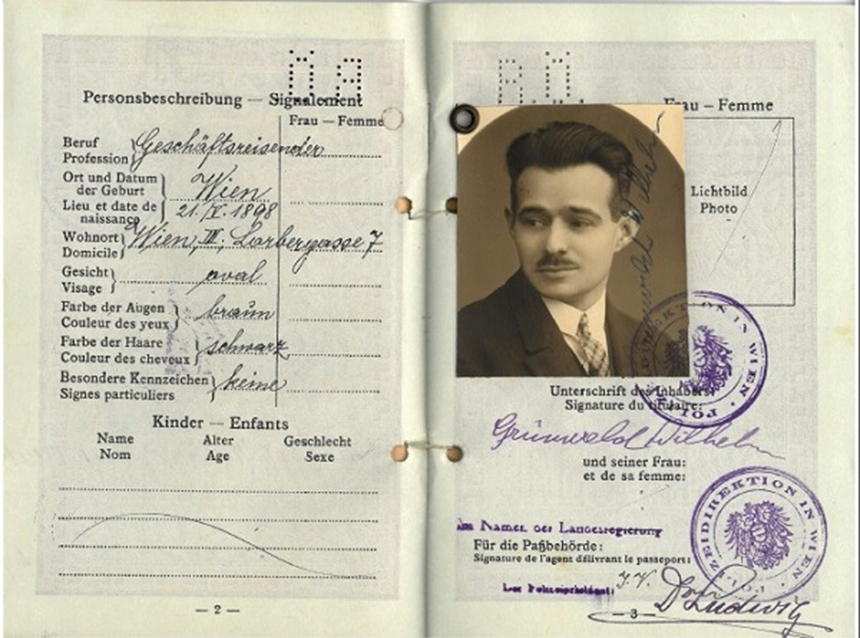

Jewish refugees, as well as Poles and Ukrainians, fled immediately after Nazi Germany attacked Poland on 1 September 1939. They moved mainly from its western and central regions, heading south, east, and toward the Baltic republics. They expected that the Polish army would be able to stop the aggressor, but that did not happen. After the Soviet Union entered the war and the Red Army occupied Eastern Poland, the situation changed, and hundreds of thousands of refugees ended up in the "zone of Soviet interests." Some of them eventually tried to return home. But after guards were stationed at the new border, this journey became fraught with danger. At the same time, the stream of Jewish refugees from territories occupied or annexed by the Third Reich (Poland, "Ostmark," i.e., Austria, and "the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia," i.e., Czechia) continued because the Nazi occupiers had introduced such anti-Jewish measures as dismissal from work, expulsion from homes, deportation, synagogue burnings, execution, forced labor, etc. Among the refugees were approximately 3,900 Jews from Vienna, Katowice, and Moravská Ostrava. In October 1939, the Nazis transported them to the Nisko railway station in the former Lublin voivodeship to set up a "Jewish reservation" there. However, the Reich Security Main Office in Berlin rejected these plans due to inadequate coordination between all the structures involved and the complex military and political situation. The deported Jews were directed toward the demarcation line between the "spheres of interests" of Germany and the USSR. Many of the deportees went voluntarily to territories controlled by the Red Army or were expelled there by the Germans, who threatened to shoot them if they refused to go. In many cases, German police officers pushed Jews toward the Soviet side. The Soviet government protested these actions and tightened border control.

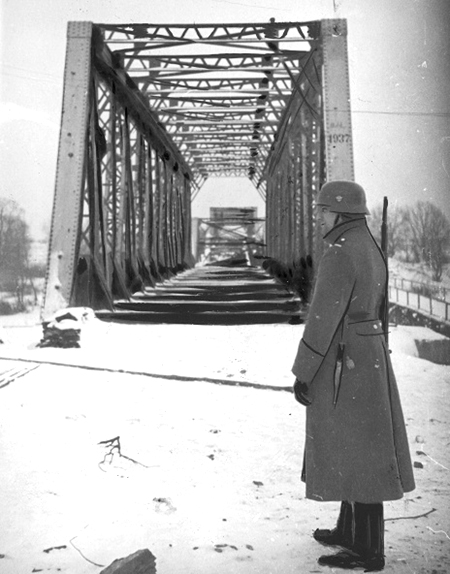

How accessible was the border crossing to refugees in 1939–1940?

By mid-October 1939, there was still no regular control over the border. Refugees moved erratically and were in mortal danger from German bombing and shelling in active combat zones throughout September. Once control over the new border was established, people attempting to enter Ukraine's western oblasts through the so-called "green corridor," that is, illegally, faced new risks: drowning in the Sian or Buh rivers, prison, deportation to the German side, freezing to death in winter, or being robbed. Despite everything, Jewish refugees strove to enter Soviet territory to save themselves from the Germans. Reports issued by the NKVD Border Troops attest to this.

"Most Jewish refugees were in Lviv and Białystok"

In which regions and cities did the largest number of Jewish refugees settle? How did they affect the ethno-demographic structure in those places?

When the war began, refugees found themselves in Eastern Galicia and the Białystok and Brest areas. Some had relatives living there who offered them assistance. October 1939 marked the start of registration. Following the order of Lavrenty Beria, Peoples' Commissar of Internal Affairs of the USSR, refugees were divided into three groups. The first group included people who, in early October, had retreated after the Red Army to areas beyond the demarcation line and were then directed to the central regions of Ukraine. Unfortunately, owing to the lack of archival sources, it is exceedingly difficult to determine their exact numbers, but there were at least three to four thousand. The second group consisted of refugees from territories occupied by the Wehrmacht who wanted to return home. The third group were refugees who wished to remain in the Soviet Union. As of 16 October 1939, 214,000 people were registered in three former voivodeships of Eastern Poland. Some historians say there was an equal number of unregistered refugees, and the total number could be 400,00 to 500,000. Most Jewish refugees were based in Lviv (over 65,000 as of 23 November 1939) and Białystok (a little under 66,000 as of 5 February 1940). Since most of them were Jews, the Jewish population in these two cities grew significantly.

What were the socioeconomic conditions that Jewish refugees from Poland, Austria, and Czechia encountered? Did the Soviet government provide them with proper conditions?

The largest concentration of refugees was observed in districts near the new border. Issues related to employment, housing, food supply, and the risk of infectious diseases, like typhus, created a very tense situation. Committees to aid refugees were established in many cities. One way that the Soviet authorities tried to ease the crisis close to the border was to suggest that refugees and unemployed people move deeper into Ukraine and Russia. This proposal resonated with many of them, and nearly 33,000 persons made the move by 1 February 1940. The number of registered refugees in Lviv oblast dropped to 40,000 by late January 1940. The Council of People's Commissars and the Central Committee of the Communist Party (Bolsheviks) of Ukraine ordered oblast executive party committees and oblast party committees "to create working conditions for refugees and former unemployed people." However, this decision did not have a significant impact on the situation in the country because, owing to the inefficient Soviet economy, the authorities could not ensure that the population had an adequate standard of living. For the majority of refugees, this meant rapid impoverishment and disillusionment with the Soviet Union, which strengthened the desire of the refugees, including Jews, to return home.

How did local residents, especially members of Jewish communities in Ukraine, treat the arrival of thousands of these migrants? How did the influx of many refugees affect interethnic relations in Ukraine's western oblasts?

Jewish communities tried to help the refugees. However, it is difficult to determine the scope of this relief given that the socioeconomic situation in Ukraine's western regions, above all in Lviv, was rapidly worsening, both because of the war, which had destroyed traditional economic ties, and nonsensical Soviet policies and their executors. To make matters worse, the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee ("Joint"), a well-known humanitarian organization, was banned in the USSR in 1938 and could no longer help Jews there after that. At the same time, before the U.S. entered the war in December 1941, the Joint was officially helping Jews in Nazi-occupied territories, including ghetto prisoners in Poland.

Interethnic relations are affected by various factors: prolonged coexistence of multiple ethnicities, the social characteristics of specific participants, the impact of political, ideological, and economic factors, and others. In the case of the refugees, since we are talking about a multidimensional crisis, I am convinced that it is not possible to gauge with any certainty the local non-Jewish population's attitude towards the Jewish refugees, even though there are some examples. The Belarusian historian Yevgeniy Rozenblat, for one, contends that the presence of large numbers of Jewish refugees led to the intensification of antisemitic and anti-Soviet feelings. He equates Soviet functionaries with Jewish refugees, which seems odd because refugees could usually count only on low-paid, unskilled work, and the Soviet authorities treated them with suspicion.

The large concentration of refugees in various cities also had a negative impact on the humanitarian situation. However, extant written sources contain a small number of examples of value judgments about Jewish refugees, although the few that exist are eloquent. For instance, in his notes entitled Escape from Lviv to Warsaw, the distinguished Ukrainian politician and journalist Osyp Nazaruk writes about Jewish refugees with great sympathy. At the same time, he was troubled by the question, "How will our people be able to withstand so many people engaged exclusively in petty trading!" Entirely different fears preoccupied Ivan Serov, the newly appointed People's Commissar of Internal Affairs. In an intelligence report issued by the NKVD Border Troops of Kyiv District and dated 6 November 1939, he describes the Nazis' maltreatment of the Jewish population, noting that "this information should be verified with the help of foreign agents because the statements of border violators are frequently unsubstantiated; therefore, they must be treated with caution […]. It is difficult to imagine that a Pole would vouch for a Jew because, before the arrival of the Red Army, Poles did not call Jews anything but Żydzi. While crossing the border, they obviously tell all sorts of tales to tug at one's heartstrings." [1]

Serov's statement reveals, first of all, that he did not take Nazi antisemitism and Judeophobia seriously. Second, he misunderstood the Polish word Żydzi, which has no antisemitic connotation, as it does in Russian. Finally, Serov did not believe the commanders of the Border Troops, who noted "that the information is reliable and corroborated by other sources." It may be assumed that this indifferent attitude to the Nazis' antisemitic policies was characteristic not only of Serov but of many Soviet functionaries. In conjunction with the euphoria that was felt after the USSR annexed new territories, it played a fatal role in their understanding of the true ideology and policies of the Third Reich and its ability to attack the USSR. Less than two years later, Germany attacked its erstwhile ally, and one of the tragic consequences of this was the chaotic flight of around nine million people, including Jews, particularly Polish Jews, who were forced to flee a second time.

"Refugees began encountering problems in the spring of 1940 when some 78,000 of them refused to accept Soviet passports"

What was the Soviet government's policy toward Jewish refugees? Which groups were subject to arrest and/or deportation?

From the moment that the Red Army entered the territory of Eastern Poland, Jewish refugees were of little consequence to the NKVD, for it was focused on hunting down and arresting members of Polish state organs, army officers, leaders of political parties, and others. But as early as mid-October 1939, Beria, head of the Soviet secret police, expanded the lists of people slated for arrest. At the same time, attention was drawn to the possibility that spies working for foreign intelligence agencies might be entering Soviet territory in the guise of refugees. However, as the above-mentioned intelligence report reveals, Soviet border troops on the ground understood precisely why Jews were motivated to cross the border to the Soviet side and did not consider them a danger to the Soviet government. Problems for refugees began in the spring of 1940 when approximately 78,000 of them refused to accept Soviet passports. They hoped to return home to the German-occupied territories of Poland, as well as to Austria and Czechia, which the Nazis had annexed. Since the Germans refused to take back Jews, the NKVD organized another deportation, which took place simultaneously in Ukraine's western oblasts and Belarus in late June 1940. The refugees were placed in 229 settlements in fourteen republics, krais, and oblasts. The living conditions, even in the estimation of NKVD personnel, who were not noted for their humaneness, were deplorable. Moreover, the distribution of food, clothing, and work tools was unsatisfactory, and interethnic conflicts flared up in camps and special settlements.

The next wave of repressions, which took place in the spring of 1941, targeted those refugees who had tried to invite their families — wives, fiancés, or children. These refugees had already accepted Soviet citizenship and could not be accused of "crossing the border illegally." For these people, the Soviet "justice" system reserved the universal accusation of "counterrevolutionary activities."

In your book, you write that many of the Jewish refugees who reached the territory of Ukraine were repressed and convicted or deported to the Soviet hinterland. However, a substantial number of them remained and ended up being killed during the Holocaust. According to your data, what percentage of refugees were repressed by the Soviet state? What was the subsequent fate of the majority of convicted and deported Jewish refugees? Can the Soviet repression of the Jews be truly defined as a "lesser" evil that offered somewhat better survival chances compared to the Jews who remained under Nazi occupation? Did you come across a percentage indicating the death rate among Jews who were deported to the Soviet hinterland? We know that the survival rate of Jews living under German occupation in certain regions ranged between two and five percent of the ones who stayed.

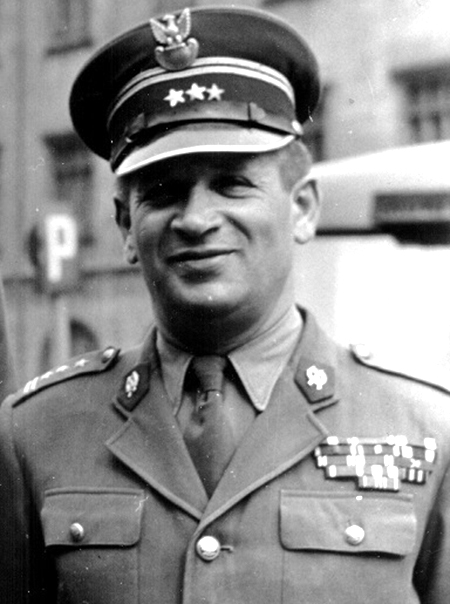

To answer your multifaceted question, I have to refer to statistics, although they are incomplete, inaccurate, and sometimes questionable for many reasons. We will move in reverse chronological order. Six thousand Polish Jews left the USSR in 1942 as part of the army led by the Polish general Władysław Anders. Between 1944 and 1946, 202,000 Jews left for Poland, and approximately 15,000 remained in the Soviet Union. According to estimates provided by Аlbert Kaganovitch, to the 244,000 Polish Jews who survived in the rear areas of the Soviet Union, one must add the 35,000 refugees who had survived in the occupied territories within the 1940 borders, as well as 25 percent more refugees — those who perished from hunger and disease in 1942–1946. This is the mortality rate that appears in a report that the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee prepared for Stalin. Thus, 282,000 Polish Jews lived in the USSR as of early 1942. If we concentrate on official NKVD data, which seems highly underestimated, the fatality rate in Soviet camps and prisons in 1942 was 2.1 percent. However, we do not have data for 1941, when Polish citizens were released in the fall. It may be presumed that the mortality rate was not significantly different because 1942 was a very difficult year due to the lack of food. Therefore, of the 64,533 Jewish refugees who were deported in the summer of 1940 (the remainder was composed of Poles — 11 percent, Ukrainians — 2 percent, and Belarusians — 0.2 percent), at least 1,350 people died.

Notwithstanding these statistics, it is impossible to determine the proportion of refugees who were subjected to NKVD repressions in relation to the total number of Jewish refugees. This is because we do not know the total number, as NKVD reports from 1939 and 1940 only listed registered citizens. Furthermore, we do not know how many were killed in Soviet territories occupied by the Wehrmacht. The only thing that we can presume based on existing data is that, at most, 23 percent of the total number of refugees (282,000) were repressed by the NKVD. If we consider the possibility that half of all refugees may not have been registered, this proportion should be halved. In any case, these estimates pertain only to Polish Jews. The survival chances for Jewish refugees were significantly higher in the rear areas of the USSR than in German-occupied territories. Undoubtedly, all survivors were left with traumatic memories after their difficult trials.

An entirely different statistical picture emerges with regard to the 1,600 Jews whom the Nazis sent on two transports from Vienna to the Nisko railway station in October 1939 and later pushed to the Soviet side. In the summer of 1940, the NKVD deported them to the northern regions of the USSR and Siberia. Their stay in the camps was extended in early 1942 since most of them were from Austria, an ally of Nazi Germany. They were released only in the winter of 1946, eighteen months after the war ended. The terms of their incarceration in camps were twice as high as their sentences and five years longer than for refugees who were former citizens of Poland. Those who were lucky enough to survive and be released tried once again to return home, but their efforts sparked new repressions by the Soviet authorities. The driving force behind these repressions was the Cold War between the former members of the anti-Nazi coalition. Only in the second half of the 1950s, after the international regulation of Austria's status, did the CC CPSU hand down a special decision allowing former Austrians still residing in the USSR to return to their country. As a result, we know the surnames of 80 individuals who returned home, although some of those transported to the Nisko railway station could have remained in the USSR.

How often did you connect with the descendants of Jewish refugees? Do they ask you for help with learning what happened to their relatives?

The events that took place 85 years ago do not belong exclusively to historiography or the politics of memory. There are quite a few descendants of refugees who have not lost hope that they might discover the fate of their parents or grandparents. Modern means of communication allow us to establish contact quickly. Unfortunately, uncovering even small bits of information is not always possible. So, I am delighted by any success in this regard. Relatives of refugees usually share documents and photographs from their family archives, for which I am profoundly grateful. I am glad that the blood relatives of the refugees who perished or went through the hell of Nazi antisemitism and the GULAG are being found. For me, this is proof that life goes on, and that is highly motivating.

To conclude our conversation, I would like to take the opportunity to express my deep gratitude to all those who helped me in word and deed to collect and work on the materials for my book about Jewish refugees: first and foremost, the staff of the Branch State Archive of the Security Service of Ukraine (HDA SBU); the SBU Archives of Lviv and Kherson oblasts; and the state archives of Vinnytsia, Volyn, Kirovohrad, Lviv, Ternopil, and Kherson oblasts. My work benefited from exchanging ideas with Yuri Shapoval, Claudia Weber, Tetiana Pastushenko, and Viktor Bilous. I also owe a debt of gratitude to Leonid Finberg and the staff of the Dukh i Litera publishing house for their comprehensive assistance.

Interviewed by Petro Dolhanov

All the photographs are from Olga Radchenko's archive.

Endnotes

1 Branch State Archive of the Security Service of Ukraine (HDA SBU, f. 16, op. 1, spr. 382, fols. 277–78.

Olga Radchenko is a Candidate of Historical Sciences, associate professor, and fellow at the Department of Modern European History, European University Viadrina Frankfurt (Oder), Germany. In 2001–2002 and 2006–2023, she taught at Bohdan Khmelnytsky National University of Cherkasy. Her research interests include refugees during the Second World War, the Holocaust in Ukraine, Soviet POWs, and the history of international tourism. She is the author of Ievreis′ki bizhentsi v Ukraїni, 1939–1941 rr. [Jewish Refugees in Ukraine, 1939–1941]; Pol′s′ki hromadiany-bizhentsi v URSR (1939–1941 rr.): Istorychni narysy [Polish Refugees in the Ukrainian SSR (1939–1941: Historical Essays; co-authored with Viktor Bilous]; and 'Inturist' v Ukraine 1960–1980 godov: Mezhdu krasnoi propagandoi i tverdoi valiutoi [Intourist in Ukraine 1960s–1980s: Between Red Propaganda and Hard Currency].

Originally appeared in Ukrainian @Ukraina Moderna

This article was published as part of a project supported by the Canadian non-profit charitable organization Ukrainian Jewish Encounter.

Translated from the Ukrainian by Marta D. Olynyk

NOTE: UJE does not necessarily endorse opinions expressed in articles and other materials published on its website and social media pages. Such materials are posted to promote discussion related to Ukrainian-Jewish interactions and relations. The website and social media pages will be places of information that reflect varied viewpoints.