Olha Mukha: "Jewish culture is an integral part of Ukrainian identity that we must restore"

[Editor's note: LB.UA, one of Ukraine's leading publications, ran a series of interviews with jury members for the 2023 "Encounter: The Ukrainian-Jewish Literary Prize" ™ before the prize winner was announced on 18 September 2023. The interview with jury head Olha Mukha appeared in Ukrainian on 17 September 2023.]

By Marta Konyk

Originally appeared in Ukrainian @lb.ua

This is the third year that the "Encounter: Ukrainian-Jewish Literary Prize" is being awarded. In 2020, the winning novel was Vasyl Makhno's Eternal Calendar, and in 2021, the prize was awarded to the Ukrainian translation of Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern's book The Anti-Imperial Choice: The Making of the Ukrainian Jew. In 2022, no prize was awarded because of Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

The members of this year's jury were the philosopher and researcher Olha Mukha; the translator, publisher, and journalist Oksana Forostyna; and the historian and writer Olena Styazhkina. We spoke with each of them about literature during the war and the role of the prize. Part 3 of our series features a conversation with the jury head, Olha Mukha, who reflects on how Ukrainians in 2023 are researching identity through literature and art.

How does the value of the Encounter Literary Prize 2023 stack up against other prizes?

Literary prizes are generally important. Lviv has been named a UNESCO City of Literature, and I was one of those who advocated for the need to establish a prize in the sphere of culture, especially literature. Prizes define our life priority. They best demonstrate our values, and values create a worldview, the direction in which we are moving, how we are moving, what we live by.

This Ukrainian-Jewish literary award is an important moment of restoration. It is difficult to contemplate the history of Ukraine without the Jewish component. Recently, I attended several international conferences, where people have asked me, "Why are there so many Jews in Ukraine?" I say, "Well, that is our historical legacy." In other words, it must be recognized that Jews were living in that very same Lviv as early as the fourteenth century. At the beginning of the twentieth century, before all the horrific events of the world wars, Jews formed nearly 25 percent of the urban population. One cannot contemplate the history of Ukraine in the global dimension without mentioning, for example, the most dominant subgroup of the Jewish people, the Ashkenazi.

As for why this is important today, I will offer this from the external perspective: "See what failed Nazis we are." At one conference several days ago, some foreigners said jokingly, "How is it that you are Nazis if your president is a Jew and your defense minister is a Crimean Tatar?" I joke[d] back: "You can't imagine what we have on other levels." But in all seriousness, this is a weighty counter-message to Kremlin propaganda about Ukrainian "Nazism" and "brutal nationalism."

This is also an interesting factor of self-knowledge for us. For many people, even those of my generation who attended Soviet schools and younger people, quite a few things are being discovered. We spent several days in Cologne visiting the exhibition of Ukrainian modernism and had a behind-the-scenes conversation with Vakhtang Kebuladze, who just the day before had delivered a lecture on Ukrainian history as formed through literature. He says: "Who comes to these exhibitions? What is the target audience?" I say: "Listen, it's not important how many of them there are. A certain number of people have moved here under compulsion, and they are thirsty for knowledge about themselves. They are acquiring their identity here; they are discovering themselves, and this is part of our identity both through literature and pictorial art."

In addition, we have to realize that we should already switch focus. Because when people in our country say the word "Jew" [ievrei], the first associations are to the Holocaust, the mass shootings, and Babyn Yar. More than half of all Ukrainian Jews were killed; the rest were assimilated or deported. However, this history is far richer. It also boasts an immense number of "glorious" facts, friendly facts. It is about co-existence and enrichment.

What did this year's short list show us? Which leading narrative (or narratives) is common to these books?

Really different books ended up on the short list. I remember how, at the first discussion, the jury members and I said that there is only one book of poetry on the long list. How will we judge it against the others? Because poetry is judged according to completely different criteria from fiction. But after a targeted reading, we agreed unanimously: "Yes!" This book, Anna Frajlich's My Father's Name, was recommended for the short list. It hits the bull's eye of the prize. There are many common connections here, a single perception, and stories about Ukrainian and Jewish roots.

As for the other texts that made it onto the short list, we thought about whether they reflect one of the main criteria, which is basically the motto of the prize itself: the commonality of history. We checked to see if connections were being constructed here, whether Ukrainian and Jewish histories are living alongside each other. Then, we looked at other criteria, especially style, appeal, authenticity, character development, and the degree to which a given book is suitable for "external reading." The leading criteria for us was the intelligibility of relationships and their depth. Ultimately, the selection was logical but not so straightforward.

In 2020 the winner was Vasyl Makhno's book about the long-standing relations between Ukrainians and Jews in the Ukrainian lands. T `njuihyb 9 0'hat year's short list featured diverse works in terms of time segments; for example, Kateryna Babkina's book My Uncle Danced Better Than Anyone, a contemporary take on Ukrainian-Jewish relations. This year, most of the books appear to be about the Second World War, and the accent is on "during the war."

This is a very interesting moment, and I think that it was self-actualized. This year we have, on the one hand, great linguistic diversity, because not all the books were written in Ukrainian; several were translations. On the other, there are not all that many of these books. This is another important feature of the prize: to bring this topic to a higher level of public exposure in the social discourse. For us, this is a valuable context in the formation of cultural policies.

What are the themes explored in the short listed books? You already mentioned the collection of poetry. What about the others?

Ida Fink's The Garden Floats Away is written in the popular journal-type format, which is considered a powerful way of recounting history as eyewitness testimony. Sofia Andrukhovych's Amadoka is three novels in one. It explores the powerful theme of identity and includes a strong historical part that is very painful. I could not read it in one go; I had to take breaks in the parts describing Jewish pogroms, the discovery of internal relations, and cases of people saving each other.

Oleksiy Nikitin's Bat-Ami is an excellent example of a documentary novel. Reading the text with complete enjoyment requires mastery of a certain degree of historical competence. It features many stylistic devices and the use of bureaucratese [kantseliarizm] for writing minutes of meetings, when you read and recognize them. If you do not possess competence in reading this style, you think, why the devil is this written in such a dry fashion? When you realize that this is a reference to the language of reports, even in terms of structure, in the very language [of the novel], then this gives a completely different nuance to the reading.

Ivanna Stef'iuk's book About You is a collection of photographs. The text is written in a unique local language featuring dialecticisms — it will be a challenge for any translator. In the sense of reading authenticity and the terminology that is used to characterize relationships or events, it is very, very interesting. It approaches the reader in a completely different way. It is perceptive. It is about experiences, emotions, and feelings on the road to self-knowledge.

To put it bluntly, the general theme of the short listed books is a quest, prospecting for identity, prospecting for one's own. It very much resonates with what is happening to Ukrainians right now, and Jews as well.

So, how is this list interesting in the year 2023? It is interesting in terms of the discussion about Ukrainian forced émigrés. In my collection, I have a whole bunch of inspiring conversations with people who had to leave Mariupol, Kryvyi Rih, from the Donbas, from Luhansk. They say that this forced them to learn who they are, who we are, why the Ukrainian [language]. Most of them were able to switch to Ukrainian; not everyone managed, for various reasons, but I see that there is an effort, there is a demand for this.

Many city residents visited the "In the Eye of the Storm: Modernism in Ukraine 1900–1930s and Daria Koltsova" exhibition in Cologne, which I have already mentioned. Ukrainian émigrés in Cologne now comprise 18 percent of the population, according to one city resident. A lot of people were from this particular social group; some of them came from other parts of Germany with the express intention of attending this event. Some were professional art historians, mostly women, for obvious reasons. But there were also people who simply wanted to ask questions about everything: "That's ours too?! Alexandra Ekster is ours? Chagall is from our region, not from Paris? Malyvych?" I think that this is a great re-discovery — of oneself, of one's relationship with the world.

Many Soviet-era myths remain, particularly the one about Ukrainian-Jewish relations. The myth about constant fighting and mutual hatred was nurtured for a long time. But if that were so, how is then that so many Jewish communities functioned so successfully? How could they have occupied a prominent place in the social hierarchy if that were the truth? Sometimes, it is enough simply to look at a few historical materials and documents to put everything in its proper place. But in order to shift the whole perspective, more time and cultural work are needed.

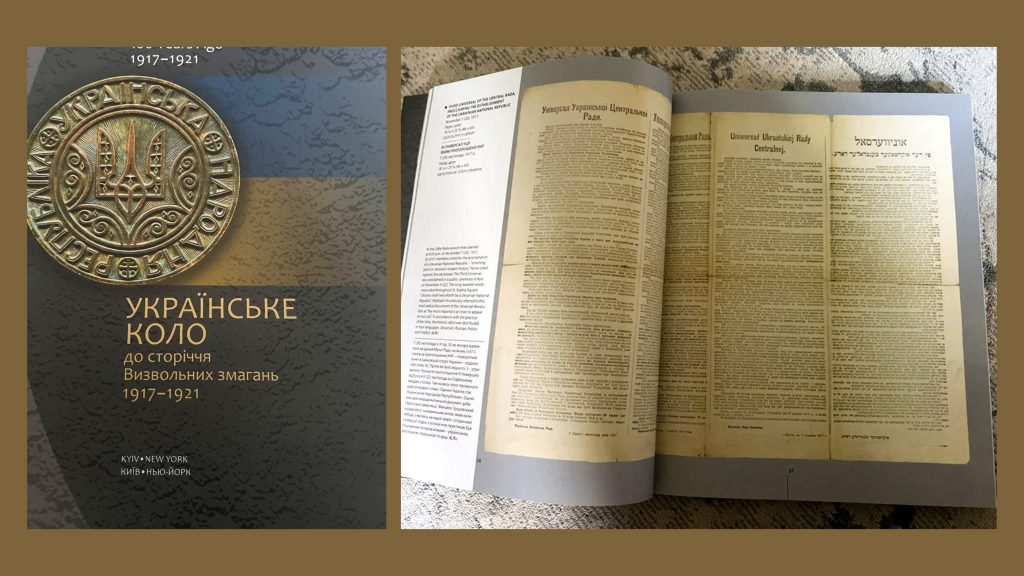

I remember when The Ukrainian Museum in New York held an exhibition called "Full Circle," which was pegged to the centennial of the liberation struggles; it was a real discovery for me to find out that the Third Universal of the Ukrainian National Republic was written in four languages: Ukrainian, Russian, Polish, and Yiddish. How beautifully the notion of "in keeping with historical practice" was substantiated there. In other words, this was an absolutely typical state of affairs.

Or take, for example, the text of the oath of loyalty to the Ukrainian state sworn by military personnel of Jewish nationality. Since such an official document exists, we realize that this was a long-standing and widespread practice. "I promise and swear to the Lord G-d Adonai, G-d of Israel," and so on goes the oath of loyalty to Ukraine as to their own state. There is no internal conflict along the lines of, "These are not our people," "This is not our flag," etc. Through the discovery of historical facts or documents, we are arriving at an understanding of what the historical reality was. But only literature is able to give it vividness to imagine the way things were on the everyday level, in relationships, in romantic stories.

Here is a question for you as someone who has been working for several years with the Territory of Terror Memorial Museum in Lviv: In the last five years, how has work in Ukraine on this topic changed? What is the demand for research on it?

What has definitely increased is our level of knowledge, especially our awareness of how much we don't know (laughs). The Territory of Terror Memorial Museum is located on the site of Transit Prison №25, which operated from 1944 to 1955; a ghetto was located there from 1941–1943 — a tragic place. A huge number of Lviv Jews set out on their final journey from that place. The museum office, which we accidentally acquired a few years ago, located on the premises of the former library on Sholem Aleichem Street, turned out to be a former synagogue. We discovered this when we started the renovations and noticed the characteristic murals that are now being researched, conserved, and restored.

Here is some of the latest news. Recently, I began collaborating with the Dim42 [House42] project. This is a brick building located at 42 Rynok Square in Lviv. Last week, a bunker in which Jews hid out during the Second World War was discovered there; there are inscriptions on the walls, and names are scratched on them. We are learning about all these details only now, through the barely legible inscriptions on the walls, through carefully recounted family histories.

After the Second World War and later, after the Soviet Union's very harsh policies toward the Jews, their numbers in Ukraine shrank [practically] to nothing. I say this as a culturologist. We once had 800 synagogues; now 70 are functioning — that's a tenfold difference. Prior to the full-scale invasion, there were some 250 to 260 religious communities in Ukraine, most of them Orthodox and very insular.

But we need to talk about the fact that, despite everything, the general level of interest has risen, even though the topic remains a niche one. For many people, moments in Jewish history are huge discoveries, even the fact that many Jews lived in Lviv or Kyiv, although everyone knows about the Jewish New Year, Rosh Hashanah, in Uman. Incidentally, last year, I wondered whether Jews would come to Ukraine, and they did come and kept up their tradition — they [came] this year, too.

Our common history is linked to practically all Ukrainian cities, and this memory still needs to be reconstructed. In recent times, the attitude of the typical museumgoer has changed. There is more openness, willingness to accept, and sincere interest and exploration. A dialogue is taking place, and it is producing results; it is still a long journey.

That is why this prize is additionally important because it gives voice to these questions and reveals the continuity of our relations. Of course, we have quarreled. There were conflicts between us, as in any big family made up of various ethnicities. But Ukraine remains the place where Jews preserved their identity for a long period of time. Therefore, for them, it is a kind of birthplace of their ethnicity.

You mentioned that you have just returned from an exhibit of Ukrainian modernism in Cologne, where you took part in the cultural program. The exhibit features the Jewish organization Kultur-lige Art Department. How was it presented there?

Yes, this is a small but brilliant part of the exhibition. The tour guide says that this took place in Kyiv, and a visitor says: "Say that this took place during the UNR!" That is a correct remark! The information about the exhibition is in German, English, and Ukrainian; it is very important to have this linguistic subjectness. The Kultur-lige Art Department was the most prominent Jewish cultural organization of the early 1920s in Ukraine. According to the stands at the Ludwig Museum in Cologne, it was founded in Kyiv in 1918 "in a unique political context formed by the Ukrainian National Republic to foster the development of all spheres of the contemporary Yiddish culture." In other words, it is clearly stated that this was the UNR's cultural policy, not happenstance. The Kultur-lige united young Jewish artists of Kyiv and other cities. Under pressure from the Soviet regime, it ceased to exist in the mid-1920s.

The Kultur-lige was supposed to breathe new creative life into the national communities residing in the lands of the UNR. Unfortunately, this freedom was short-lived, but its fruits are still felt powerfully to this day. Yisakhar Ber Rybak, Solomon Nikritin, Mark Epstein, Sarah Shor, and El Lissitzky are world-famous names. Until recently, little was known about the Kultur-lige. You could say that this is the culture of special collections, hidden and silenced.

Serious research began in Jerusalem in the early 2000s. The Israeli researcher Hillel Kazovsky published the first book about the artists of the Kultur-lige. I recall that Leonid Finberg said that he was struck by the fact that the majority of the events described in it had taken place in Kyiv.

Later (this is another painful topic that is common to us Ukrainians in 2023 and for Ukrainian-Jewish relations of the past century), they all head out to study somewhere else because there are no prospects for continuing their studies in Kyiv. Why did branches of the Kultur-lige appear in Moscow, Warsaw, and San Francisco? First of all, the vital need to emigrate arose. Second, this was the colonization of education: It was impossible to carve out an artistic career for oneself without traveling to the center, where there was a prestigious institution of higher education. For an art academy and "artistic legitimization," they had to go to a so-called metropolis. There was a choice: either to go to St. Petersburg/Moscow or Paris.

So, this was very progressive art in its location, and the Kyivan period was the heyday of the Kultur-lige. The Kultur-lige's museum, featuring the works of Picasso, Bruegel, and Chagall, opened in 1918; provincialization then ensued. This colonizing tool in culture is very relevant. The same may be said of Slavic Studies, where departments of Slavic languages exist all over the world yet are dominated by Russian studies along with their corresponding narratives. We are reaping the results of this to the present day.

The Kultur-lige exhibit items occupy only one wall of the exhibition in Cologne's Ludwig Museum — a tiny part. So, I hope that our prize, like this wall, will remind people of an integral part of Ukrainian identity that we must restore to ourselves.

The Ukrainian avant-garde implicitly includes a Jewish focus and Jewish names. That exhibition in Cologne is iconic but of short duration, and it cannot reasonably form a trend. If we could manage to lobby for more longer-lasting exhibits, prizes like ours, joint projects on a parity basis, and to make these "infusions" into the international cultural milieu! The Ukrainian Institute has just opened an office in Germany. We are hoping that they will make such practices more present. And we shall be working on our part.

Marta Konyk, journalist

Translated from the Ukrainian by Marta D. Olynyk