Our futures are incomplete without each other

[Editor’s note: Ukrainians and Jews have lived side-by-side on the territory of modern-day Ukraine for nearly two millennia. Separately and together, they weaved a tapestry that has left an indelible mark on Ukraine’s cultural, linguistic, and historical legacy. Long periods of peaceful co-existence were also accompanied by years of tragedy, separating these two peoples through different historical experiences and narratives. Yet as the twenty-first century progresses, and as Ukraine and Israel shape their identities as independent states, shared threads remain, giving rise to a new understanding of the past.

In December 2019, the Canadian charitable organization Ukrainian Jewish Encounter, in cooperation with Ukraine’s NGO “Publishers Forum,” announced a new initiative entitled “Encounter: The Ukrainian-Jewish Literary Prize ™”. The prize aims to build on the common experiences of Ukrainians and Jews over the centuries, expressed in the written word. The “Encounter” prize will be awarded annually to the most influential work in literature and nonfiction (in alternate years) that fosters Ukrainian-Jewish understanding, helping solidify Ukraine’s place as a multi-ethnic society. The first “Encounter” prize will be awarded in September 2020 at the Lviv Book Forum.]

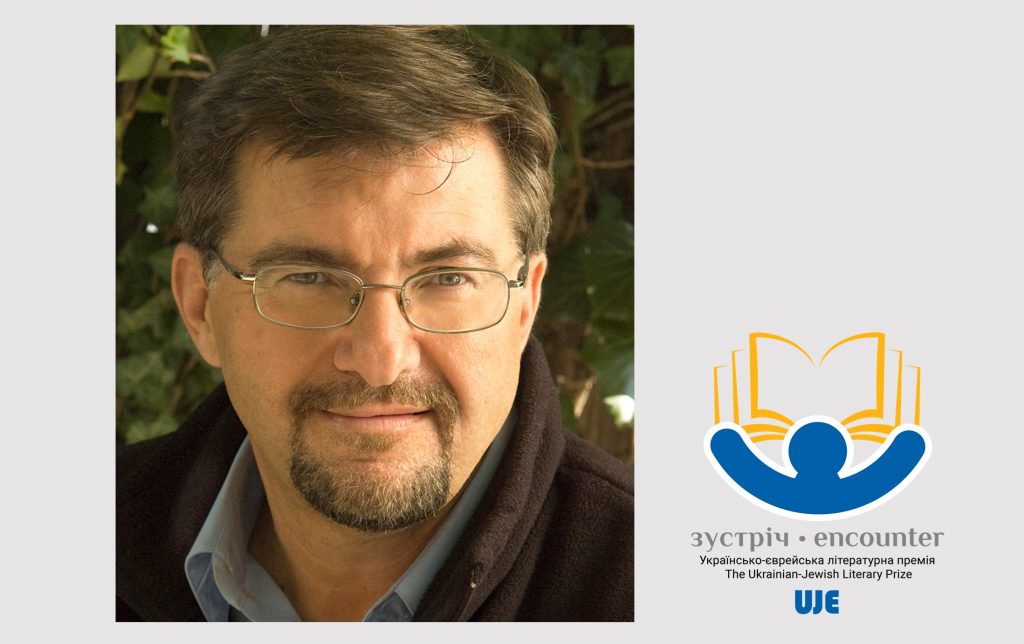

In the essay below, UJE board member and award-winning historian Serhii Plokhy reflects on the dynamics of the Ukrainian-Jewish relationship and the prize’s impact on a joint cultural and literary legacy.]

It was one of the most consequential moments in the world’s post-World War II history. On 25 February 1956, a bold overweight man walked to the podium of a congress and, in front of thousands of his colleagues, denounced Joseph Stalin and his cult of personality. The man was Nikita Khruschev. The gathering was the Twentieth Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union that was long run by Stalin.

Khrushchev’s move was a risky one. It angered many Stalinists, provoked a failed coup against him the next year, and caused the Soviet-China rift that was never healed. However, Khrushchev’s act of courage helped to turn an all-important page not only in the history of the Soviet Union but also in the history of the world, ending an era of dictatorships that ruled a good part of it for the previous thirty-plus years.

Khrushchev recalled that he was encouraged to make his speech in part by the example set by a literary character created by Volodymyr Vynnychenko, an author who was portrayed by Soviet propaganda as a Ukrainian nationalist and whose writings were banned in the USSR. The character’s name was Pinya, a young Jewish shoemaker, depicted in Vynnychenko’s 1913 short novel, Talisman. Pinya is portrayed there as a young prisoner who was held in disdain by the more mature and experienced convicts. They elected him to be the cell leader to mock and undermine the prison’s administration and the rules imposed by it.

Pinya nonetheless surprised everybody when the time came to lead the escape out of the prison. He showed his leadership and manifested his courage by becoming the first to go through the tunnel dug up by the prisoners and died, leading them out of captivity. “That is how it happened at the Twentieth Congress,” recalled Khruschev. “Once they elected me the first secretary [of the party], I, like that shoemaker Pinya, had and was obliged to tell the truth about the past, whatever was the cost to me and whatever was the risk.”

This story, told by Khrushchev more than once and reflected in numerous accounts both Soviets and Western, sounds counterintuitive at best. A Soviet leader encouraged to start an anti-Stalinist campaign, drawing on the example set by a Jewish artisan, depicted by a Ukrainian writer? What could sound more incredible? But this is what the power of the literature and the images it creates can do, make the unbelievable believable, and the impossible possible.

The movement across boundaries that divide the Ukrainians and the Jews and that literature helps to cross goes in both directions. How many people know today or would believe that one of the strong influences on the writing of Sholom Aleichem was Nikolai Gogol (or Mykola Hohol), in particular, his “The Fair at Sorochintsi”? But that is what Amelia Glaser’s recent research shows so convincingly. Once again, it is counterintuitive, and again these are the gaps in our perceptions of each other that only literature can fill, enabling connections and understandings that only the power of the word can create and maintain.

The history of Ukrainian-Jewish relations is a history of centuries of living together and apart, to use Shimon Redlich’s characterization of the life in the Ukrainian town of Berezhany. That history is full of good episodes and bad, but it is anything but counterintuitive that most of what is positive in our bilateral relations was created by or are related to those people whose main preoccupation has been literature and culture. One can start with the appeal against the discrimination toward Jews in the Russian Empire signed by Taras Shevchenko, Mykola Kostomarov, and Panteleimon Kulish in 1858, and continue with the numerous examples of the sympathetic portrayal of Jews in Ukrainian literature so ably presented in Myroslav Shkandriy’s book on Jewish characters in the works of the Ukrainian authors.

On the other side of the Ukrainian-Jewish divide, among the people who worked hard to bridge it, we find Vladimir Jabotinsky with his satirical pieces so sympathetic to the Ukrainian national movement, and the Jewish authors who had chosen the medium of the Ukrainian language and culture to express themselves and their relationship to the world. Those included people like Hryts’ko Kernerenko (Grigorii Kerner), a native of Huliaypole, and by all accounts, the first Ukrainian Jewish poet, whose anti-imperial choice had been so well described by Yohanon Petrovsky-Shtern.

The carnage of the revolutionary era, the horrors of the Second World War and the Holocaust, and finally Stalin’s post-war antisemitic and anti-Ukrainian campaigns, created new traumas and widened the distance between the Jews and the Ukrainians. However, even in the most difficult of times, there were cultural and literary figures who kept the emotional ties between the two communities alive. Ivan Kulyk, Natan Rybak, and Leonid Pervomaisky made a major contribution to the Ukrainian literary process of the period. And in September 1966, a young Ivan Dziuba delivered a short speech at the memorial meeting at the Babyn Yar, taking the torch of fighting antisemitism from an earlier generation of Ukrainian writers, represented at the event by Borys Antonenko-Davydovych.

The “generation of the Sixties” helped to create new foundations for the Ukrainian-Jewish dialogue and mutual understanding that continues to this day. Similar to the one that came into existence in the early twentieth century, the dialogue forged in the 1960s came out of the “anti-imperial choice” and was made with a huge personal sacrifice. It continues to exist today in new circumstances, and not only faces new challenges but also takes advantage of new opportunities. Unlike the case in the past, both the Ukrainians and the Jews today have states that they proudly call their homes. Both nations are dedicated to the democratic development of those states, and both have in their mix significant groups that have allegiance to either Jewish or Ukrainian culture and tradition, and more than often, to both simultaneously.

We are in a new world today and have to bring our age-old relationships in line with its demands and expectations. There has hardly been a better time to take new and bold steps into the future, but as in the past, there is hardly a better medium to forge the cultural and emotional ties and understanding between the two groups so close, and at times so separate, than literature. People who create it very often feel the pain of injustice more than others in their societies, but they are also more willing than others to explore its origins and find the healing, and most importantly they have a gift to endow us all not only with visions of the past and present but also of the future.

The book prize established by the Ukrainian Jewish Encounter is very much about making the stories that are incomplete today, complete tomorrow. I have every reason to believe that it will help to achieve that goal and wish success to its participants and winners, but most of all to the readers and communities that have so much to learn from each other.

Serhii Plokhy