Paul Celan: Avant-garde poet after Auschwitz

As a poet who was born in Ukraine and survived the Holocaust there, Paul Celan was able to speak clearly on the issue of poetry in times of catastrophe. His response is still relevant today as the world again resembles the 20th century.

It all started with Chernivtsi

The city of Chernivtsi, the capital of the Ukrainian region known under the poetic name Bukovina, has a special flavor, which, however, can be called structurally typical for Central and Eastern Europe. First of all, it is a mix of cultures and languages in the shadow of the Carpathian Mountains. Even today, after all the cataclysms of the 20th century, Ukrainian, Russian, and Romanian can be heard in the city, and cultural projects represent many more countries and peoples. A century ago, the city's cultural landscape was even more colorful. Mutual influences of Ukrainian, Romanian, Jewish, and German elements abounded, with the addition of Polish, Russian, and, earlier, Ottoman. For example, the Turkish Well (with ornaments referring to a legendary unsuccessful courtship of a Ukrainian woman by a Turkish pasha), a Jewish mikvah (a reservoir for ritual ablutions), and an Orthodox church stood side by side in one of the squares for a long time.

Naturally, the interethnic relations were not always idyllic. The atmosphere of the 1920s and 1930s is eloquently captured by the Bukovina native Israel Chalfen in his book Paul Celan. A Biography of His Youth:

"The monument to Schiller in front of the city theater had to give way to the statue of the Romanian national poet Eminescu in 1918. However, the public park located behind the theater is still called Schiller Park. From its highest point, one can easily see the western depression, in which the Swabian village of Rosch and Mount Tsetsino stand out clearly. Jewish excursionists who organized trips to Tsetsino on Sundays had to reckon with the rocks thrown at them by the Roshi youth."

Tensions increased in 1918 with the fall of Austria-Hungary, which kept its subjects within limits, constructed balances, and drove contradictions deep under the surface. Romanian control over Bukovina and the policy of Romanianization became trigger points, but the Chernivtsi community continued to adhere to multiculturalism. German-speaking Jews remained a powerful element of the city's mosaic. It was in this community that Paul Antschel, the future poet Paul Celan, was born in 1920. His father, a timber trader, had Zionist views, while his mother adored German literature and taught her son to use the "correct" German pronunciation. There was little left of traditional Jewish culture in them. It was a fairly modern, poor family. Their only son was under very stifling care, which probably contributed to him developing a quite nervous personality. At the same time, his love of reading became more and more evident, as well as his desire to be the center of attention, whether as a teacher's assistant, a key member of a youth group, or as a poet later.

In search of one's true self

In the 1930s, Paul was looking for his own way of interacting with the world. He overcame his father's influence and pressure, particularly his political imperatives. Contrary to his father's Zionist orientation, Paul, like many of his generation, preferred left-wing views. He attended meetings of an anti-fascist circle and took an interest in left-wing political thought.

Marxism, especially of the Soviet type, did not fascinate him, but he was sympathetic to figures such as Kropotkin and Trotsky. Chalfen, the biographer of Celan's youth, offers an amusing psychoanalytic comment here:

Russian anarchism, which protested against the "father tsar," corresponded to Paul's own rebellion against his father. His later sympathy for Trotsky, who was expelled from Russia, as the rejected "son of the revolution" allowed him to identify with the figure of a son persecuted and humiliated by "father Stalin."

Meanwhile, the ultra-right "triumph of the will" disrupted Paul's and his family's plans and dreams about his education. He was supposed to study in Vienna, where they had relatives. Vienna was an old metropolis associated with education, culture, and development. He was expected to master a respectable profession (such as medicine) that would help him live comfortably amid the harsh realities. However, after the perturbations in Austria, which ended with the "Anschluss," studying in Vienna was out of the question, while the Antschels' relatives barely managed to flee to Great Britain.

The dream city was out of reach, and the young man went to study medicine in France at the University of Tours. At that time, in 1938, a Jew with a Romanian ID could still transit through Nazi Germany without hindrance. In an ironic twist, he passed through Berlin the morning after Kristallnacht, an event he depicted in the poem "La Contrescarpe" years later.

Break the breathcoin out

of the air around you and the tree:

That

much

is asked of him

whom hope carts up and down

along the hearthumpway — that

much

at the curve

where he meets the breadarrow,

that drunk the wine of his night, the wine

of the misery-, the kings-

vigil.

Source: ronslate.com (on the Seawall)

Studies in France continued until 1939. Then, during the holidays, World War II broke out. Another failure. He had to enroll in Chernivtsi University. This time, Paul chose not medicine (he said he planned to return to it after the war) but philology, specifically the French language and culture.

During his student years, Paul rose to new levels of freedom from his father, and their relationship cooled. In contrast, his ardent love for his mother never faded, including for literary reasons. Chalfen believes that devotion to his mother, in some sense, kept Paul restrained in his relationships with the opposite sex. Nevertheless, he was becoming more active in communicating with girls, while guys had less interest in poetry and literature overall. Naturally, poetry did not exclude eroticism, and erotic manifestations were quite extravagant.

Ilse Goldman, one of Celan's lovers, recollected:

"I met Paul when I was fifteen and he was almost sixteen. We were then somewhat popular among young people, each for our own reasons. As I was swimming in the Prut in the summer, I suddenly noticed someone stubbornly following me — even to dangerous spots. We were both good swimmers. Finally, he said unhappily: Miss, you mistake me. I have no evil intentions; I'm pursuing you for completely different reasons, because of your ideas. I want to talk to you about your ideas."

In the summer of 1940, Paul met the actor Ruth Lackner, who became his main relationship in his early youth. Ruth inspired him to write many poems and preserved a significant part of the texts through the tumult of the war.

New reality and the translation profession

Meanwhile, fulfilling the terms of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, the USSR issued an ultimatum to Romania, demanding that it hand over Northern Bukovina (with Chernivtsi), Bessarabia, and what is now right-bank Moldova to the Soviet Union. Romania obliged, and the Soviet army entered Chernivtsi on 28 June 1940.

Paul Antschel and his friends seemed to have accepted the new reality with cautious optimism. They were now free from the pressure and restrictions (including antisemitic ones) of the increasingly nationalist Romanian authorities. However, the replacement was not free socialism but totalitarian Stalinism. Paul, now a Soviet student, had to carry banners at "voluntary-mandatory" Soviet rallies, and witness deportations to the East, denunciations, and arrests. At the same time, he also got to know the Ukrainian and Russian languages and cultures better, which played a role in his later life. Translating Russian literature into Romanian became a side job. Paul was also in dialogue with Russian poetry, for example, with Mandelstam and Tsvetaeva, during his years in Paris. He even jokingly wrote about himself, "Pawel Lwowitsch Tselan, Russian poet."

What about Ukrainian? It was not the most widely spoken language in Chernivtsi in the first half of the 20th century, but it was always in and around the city. Paul Antschel must have heard it regularly as a child and could have some Ukrainian language proficiency. Ukrainian was studied at Chernivtsi University in 1940-41 under the Soviets, and Petro Rykhlo, Ukraine's primary authority on Celan, refers to a Soviet questionnaire in which the poet indicated that he spoke the language. However, our language and culture were hardly important for Celan. It would have been too difficult for him to come across such examples of Ukrainian literature and culture that would have correlated with his tastes and interests (in particular, modernism, avant-garde). There was no large-scale Ukrainian literary environment of this type at that time in Chernivtsi. In order to read the relevant literary and artistic periodicals, one had to dive very purposefully into this area and habitually read in Ukrainian. Meanwhile, Paul Celan. A Biography of His Youth contains a curious story about his visit to a Ukrainian theater sometime in 1940-1941:

Instead, Paul happily visited the Ukrainian theater, whose performances took place in the hall of the former German, later Romanian, theater. There he enjoyed the involuntary comedy that arose in the performance of talentless actors playing in famous classical tragedies. With vivacious facial expressions, he imitated their excessive gesturing and ridiculous accentuation.

Antschel worked as a Ukrainian-Romanian translator for the local Soviet newspaper Bucovina Sovietică in 1945. Excellent language skills enabled him to translate between two non-native languages.

Chernitvi under Romanian rule again

In 1941, World War II reached a new level when Nazi Germany and its allies attacked the Soviet Union. The most brutal front and regime were in the occupied territories. Chernivtsi again found itself in special circumstances. For participating in the war on the side of the Axis and helping Germany out with oil, Romania was allowed to occupy Bukovina, Bessarabia, and the so-called Transnistria, i.e., the territory between the Bug and the Dniester, particularly fragments of what is now Vinnytsia, Mykolaiv, and Odesa regions of Ukraine and the city of Odesa. On 5 July 1941, the Romanian authorities and the Romanian army returned to Chernivtsi, accompanied by German units. Paul Antschel was among those who did not evacuate with the Soviet army because of either not perceiving mortal danger in the prospect of being ruled by "Greater Romania" or not willing to leave home.

What he faced was a completely new regime. "Greater Romania" was a state with a distinctly fascist spirit. The military decline was accompanied by brutal repressions on political and ethnic grounds, including the extermination of Jews. According to historians, the Romanian Holocaust at times inspired even German "teachers" with its cruelty, but overall, it was less consistent and not as wide-sweeping. The Jews of "Greater Romania" had more ways to escape. The population of Chernivtsi was fortunate to have Traian Popovici appointed city mayor. He was neither a fascist nor an antisemite and constantly tried to alleviate the situation of the Jews, seeking leniency from higher authorities.

For a while, the Antschels avoided deportation to "Transnistria," where Jews were dying en masse in labor camps from rapid exhaustion and executions. Paul had to do forced labor in Chernivtsi. After another increase in antisemitic pressure, the family found themselves outside the law, again facing deportation. Israel Chalfen writes that Paul, with the help of Ruth Lackner, found a place to sleep for himself and his parents to avoid spending nights at home where they could be arrested. However, the parents did not want to hide due to apathy and exhaustion. They also hoped to be able to survive in the camps. According to one version, the parents themselves found a place to sleep, specifically for their son. Paul went to his hideout alone. When he returned home, the apartment was empty. His parents had been taken to "Transnistria," where his father would die from typhus, and his mother would be shot. Such a dramatic loss, especially of his mother, was a huge trauma for the poet, poisoning his later life.

Paul soon became "legalized," hoping to be assigned to lighter forced labor than in "Transnistria."

Paul worked at a road construction site, presumably in the vicinity of Terebești, near the ancient city of Buzău, a hundred kilometers from Bucharest. Life was hard there, but one could survive and even receive a vacation. Paul wrote poems and sent them to Ruth.

In 1944, he was finally able to return home. By the end of the war, Romania was gradually distancing itself from Nazi practices, and the surviving Chernivtsi Jews could breathe a bit more freely and sometimes even step out of line. For example, in the spring, Paul Antschel was so eager to see the awakening of nature in the People's Garden (now Taras Shevchenko Park) that he went there despite the park being off limits to Jews. He was detained by a police patrol but suffered nothing more than a beating.

From Chernivtsi to Paris

Chernivtsi was liberated from Romanian-German troops in the spring of 1944.

What was the next step? The experience of 1940–41 and the first months after the return of Soviet rule convinced Paul that it was not worth staying in the USSR. Unlike most citizens of the Soviet state, he had a choice. Similar to residents of other newly occupied territories, many in Bukovina had the opportunity to leave for Romania.

During the war, Paul Antschel evolved from a beginner into a serious poet, producing outstanding texts, such as the absolute classic "Death Fugue" (1944 or 1945).

Black milk of morning we drink you evenings

we drink you at noon and mornings we drink you at night

we drink and we drink

we dig a grave in the air there one lies at ease

A man lives in the house he plays with the snakes he writes

he writes when it darkens to Deutschland your golden hair

Margarete

he writes and steps in front of his house and the stars glisten and he

whistles his dogs to come

he whistles his Jews to appear let a grave be dug in the earth

he commands us play up for the dance

Source: ronslate.com (on the Seawall)

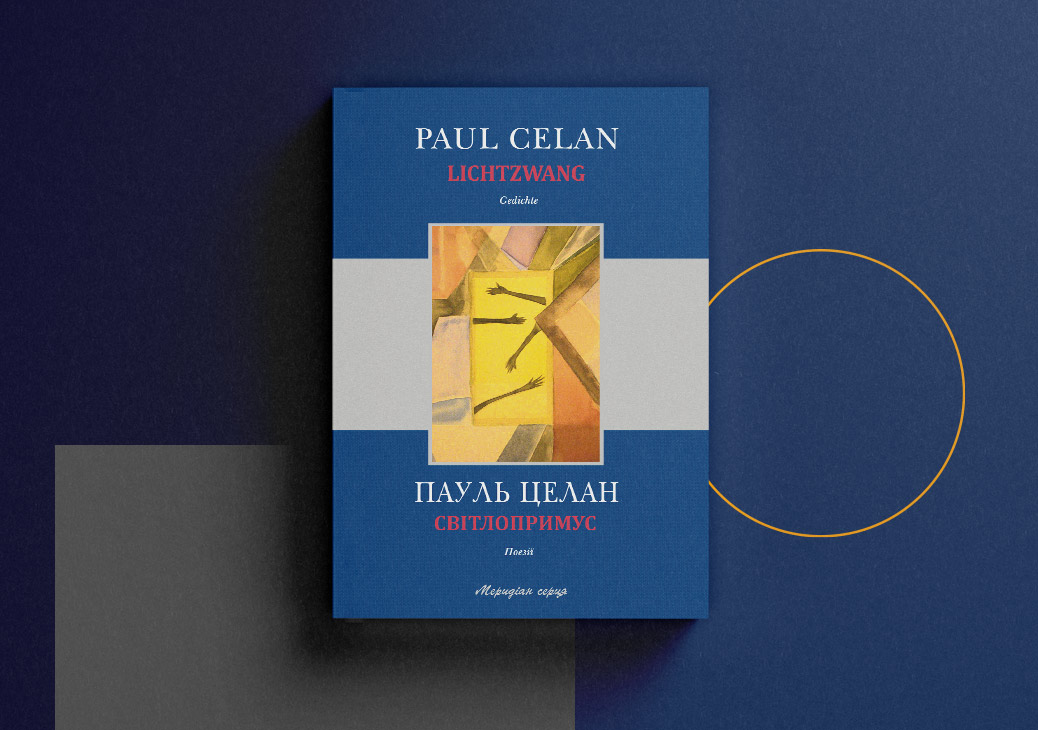

Vasyl Stus, an outstanding 20th-century Ukrainian poet, referred to the "Death Fugue," and Petro Rykhlo did a colossal job of translating all of Celan's books into Ukrainian.

Celan is believed to have borrowed the image of "black milk" from a poem by his older compatriot Rose Ausländer. She treated this as a normal intertextual practice rather than plagiarism. Immanuel Weissglas, another Chernivtsi native, a German-speaking poet, and Paul's friend in his youth, spoke similarly about the connection between his poem "HE" and Paul's "Death Fugue." They have several images in common, including death as a master from Germany. Still, the style and essence of Celan's texts are completely different despite the common "comradely counterpoints" (Weissglas' definition).

Celan's poems combined partly "neo-romantic," early modernist tendencies, more characteristic of the first years of his work, and his new explorations filled with unexpected metaphors, associative labyrinths, linguistic work at the micro level, and complex rhythms and melodies.

However, only friends knew about it at the time. Paul Antschel was yet to become Paul Celan. This happened in Bucharest when Paul arrived there in the spring of 1945. An entire "Chernivtsi community" of displaced persons had formed in Bucharest. Paul sought their support and came to Alfred Margul-Sperber, a German-speaking poet from Chernivtsi. Alfred and his wife Jessica welcomed Celan warmly into their abode. Celan had to sleep on the table as their house was crammed. In times of historical blizzards, not every reformer of poetry is lucky to have a soft bed. Alfred appreciated Celan's poetry and actively contributed to its popularization, writing perhaps the most decisive recommendation in Celan's life, which opened doors for him in the West.

The young poet received key organizational assistance from his hospitable hosts and something even more important. According to the Romanian poet and translator Petre Solomon, Jessica invented the pen name for her guest. She suggested rearranging the syllables of the Romanian version of his surname, and Ancel turned into Celan. The reshuffling appears insignificant from the perspective of a different century, language, and culture. The important thing, however, was that it was a kind of baptism. Celan believed in his new name, which did not disappoint him.

In Bucharest, Celan became close to the Romanian literary community, primarily the surrealists (he also paid attention to French surrealism). Celan wrote several poems and some short prose in Romanian and worked in the Cartea Rusă publishing house, translating Russian books into Romanian. The tragedy of the Romanian occupation in the 1940s and the Romanianization of Chernivtsi in the previous decades did not instill an aversion to the Romanian language and culture in Celan. However, he did not think he had a future there, mainly due to the ongoing Sovietization of Romania. Celan evaded Sovietization disguised as "people's democracy," illegally crossing the Romanian-Hungarian border and heading to Vienna in late 1947. When Vienna turned out to be very unlike the image of his youthful dreams, he moved to Paris.

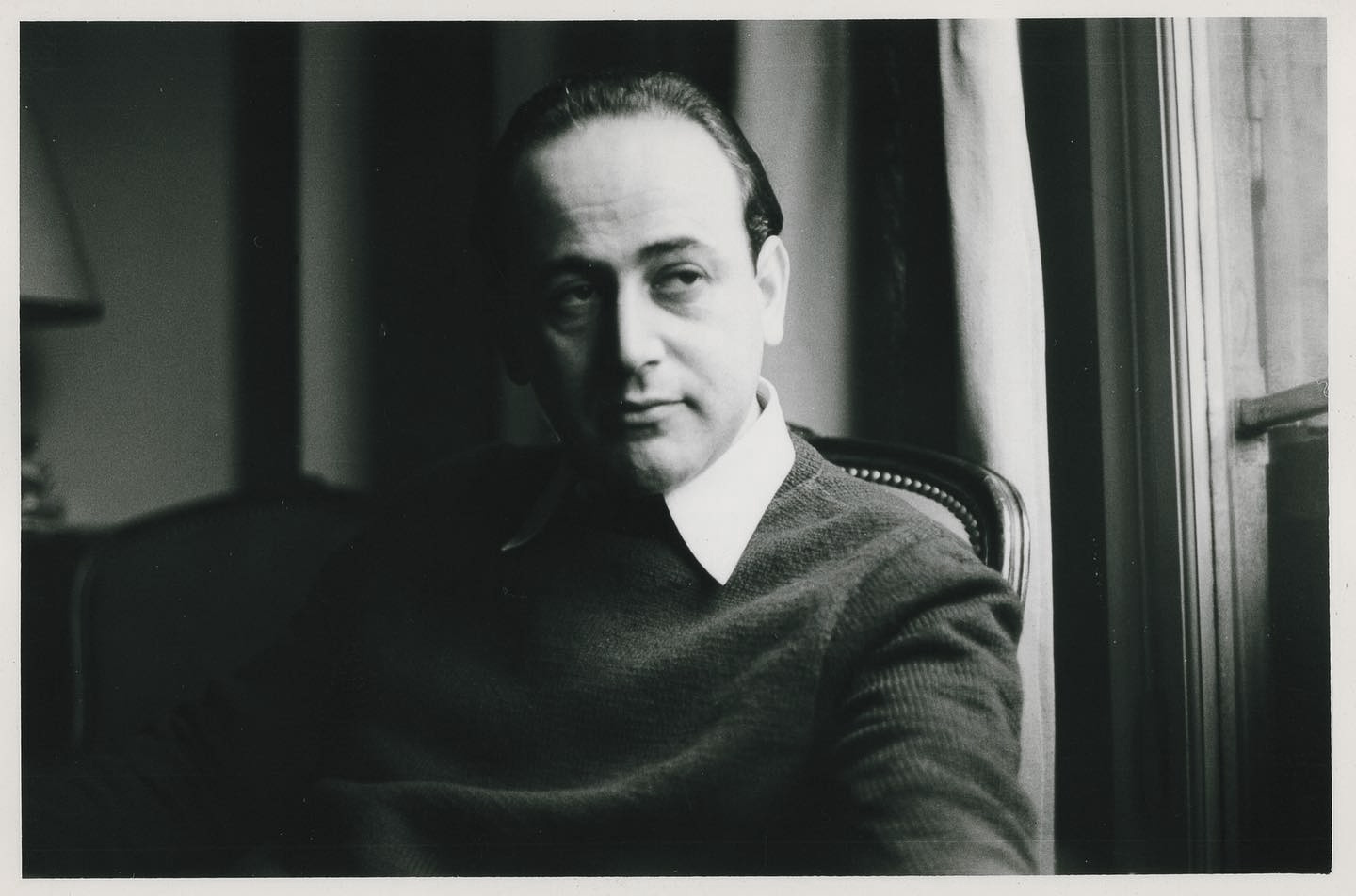

The restless Celan did not enjoy Paris very much, either. He was tormented by the isolation from the language environment, German literary life, and many friends and relatives. He was critical of the politics in the free West, perceiving a neo-Nazi flavor in the right-wing tendencies of the 1950s and 1960s. However, Celan eventually stayed in Paris, where he fully realized himself and found recognition. Celan married the artist Gisèle Lestrange, and they had a son, François, who died soon after birth, and then another son, Eric. Paris offered Celan a stable teaching job and a rich cultural life.

A poet with a unique vision

Celan's writing is fresh, bright, original, multilayered, and imaginative. In post-war Europe, it also had a considerable conceptual significance. His poetry confidently affirmed the possibility of, so to speak, "avant-garde after avant-garde." Celan was among those who showed how, after the exhaustion and fading of the "classical" avant-garde with its manifestos and overly ambitious projects for changing the world, it was possible to develop experimental, complex, and wilful poetry in a new way, using the methods and achievements of surrealism or expressionism, among other things. (It was no coincidence that one of the first translators of Celan's works into Ukrainian was Mykola Bazhan, a master of the avant-garde and modernism in the 1920s.) This kind of poetry involved post-war humanistic thought while adding some mysticism, particularly of the religious variety. It integrated into new communicative realities but avoided excessive simplification and catering to trends.

It is easy to perceive how these features (far from exhaustive, of course) of Celan's explorations are echoed in the works of the New York School of Poets or the New York Group of Ukrainian émigré poets. Remarkably, Celan's private library contained as many as nine books by Emma Andijewska. Petro Rykhlo notes that Celan intended to translate some of her largely surrealist works.

Paul Celan also convincingly demonstrated that "poetry after Auschwitz" was possible. The tragedy of the Holocaust often comes up in the associative fabric of his poems. While the trauma and pain of loss were constantly there, the topic of the Holocaust drew attention to Celan's poems and remained a source of his poetic creation.

Celan, an eyewitness and living victim, employs a fanciful figurative style without reducing his texts to a chronicle, concentrated pain, despair, or indictment. He depicts what happened after the Holocaust in the same way.

Celan's dazzling and neurotic love affair with the Austrian writer Ingeborg Bachmann was a milestone for him. This relationship must have been overshadowed in some way by the fact that Bachmann's father was a member of the Nazi party (even though Ingeborg herself had strong anti-fascist views). Celan found a way to depict this existential situation in an effective, ambiguous, and original way in his poem "In Egypt."

In Egypt

For Ingeborg

Thou shalt say to the strange woman's eye: be the water!

Thou shalt seek in the stranger's eye those whom thou knowest to be in the water.

Thou shalt call them from the water: Ruth! Noemi! Miriam!

Thou shalt adorn them when thou liest with the stranger.

Thou shalt adorn them with the cloud-hair of the stranger.

Thou shalt say to Ruth, to Miriam and Noemi:

behold, I sleep next to her!

Thou shalt adorn the stranger next to thee most beautiful of all.

Thou shalt adorn her with the pain over Ruth, over Miriam and Noemi.

Thou shalt say to the stranger:

Behold, I slept next to her!

Source: Seagull Books

The love affair between Bachmann and Celan became perhaps one of the most melodramatic episodes in the lives of 20th-century European poets. The posthumous publication of their correspondence caused a stir, although I think it was overly exaggerated, as the letters say little new to anyone except the lovers themselves. Curiously, as Petro Rykhlo notes, Ingeborg Bachmann wrote to Hans Weigel that she and Celan "took the air from each other." This almost literally matches what Ilse Goldman said of a young Paul: "Sometimes, there seems to be a kind of stuffiness around him, as in a greenhouse full of orchids."

Poetry without embellishment

In my understanding, Celan's writings "after Auschwitz" somewhat contradict his own declarations on this topic when he spoke of a search for a "grayer language," "soberer" poetic means "without embellishment," etc. I think Celan's poems, on the contrary, indicate the immense possibilities of imaginative and demanding literature during and after a horrible tragedy. Symbolically, Celan sought to meet and speak with Theodor Adorno, the author of the formula about poetry and Auschwitz, but their meeting never happened.

In this sense, Paul Celan's poetic practice and theory are especially interesting today, as we experience the biggest war since the 1940s and again face questions about poetry, its ways and means, and its impact at such a moment.

A related and complex topic is that of language. Like his friends, poets from Chernivtsi, and other German-speaking authors, primarily of Jewish background, Celan faced a painful paradox. They all wrote in a language that became one of the symbolic tools and banners of Nazism. Many came to associate it with murder, humiliation, and ideological madness.

Rose Ausländer, a German-Austrian poet of Jewish origin, "left" German-language poetry for many years and wrote in English after the war. Celan also had an escape route. He had already written a little in Romanian and could probably find his voice in French, but he chose a different path instead. Celan always emphasized his belief that poetry was possible only in the native language, and so he remained a German-language poet. This added internal contradictions to his texts and contributed to the ingenious deconstructive work with language. "It had to go through its own lack of answers, through terrifying silence, through the thousand darknesses of murderous speech," he wrote about language. Ilya Kaminsky, a contemporary American poet and a native of Ukraine, noted in his rich essay on Celan's language, paraphrasing the Anglo-American poet Wystan Hugh Auden: "Germany, no doubt, offended Celan and thereby ignited his strongest poems."

The Holocaust experience seemed to bring Paul Celan back to his Jewish roots. Before Chernivtsi was occupied, he was not a great enthusiast of Jewish culture as he happily left the Jewish school, did not take Yiddish very seriously, and generally rejected Zionism. However, the death of his relatives and the Holocaust forced him to reflect on his roots.

Thus, motifs of Jewish mysticism, Kabbalah, biblical archetypes, allusions to traditions and rituals, and Hebrew and Yiddish words emerged or intensified in Celan's poetry. His visit to Israel before death should also be considered in this context. Along with such authors as Franz Kafka and Bruno Schulz, Celan entered the annals of culture as one of the titans of Jewish literary modernism and/or avant-garde.

The Goll affair

Celan's life path was paradoxical. On the one hand, it was constant, consistent, and ever-increasing recognition, even globally, along with complete freedom of creation and without the apparent need to conform to aesthetic, political, or any other fashion. Isn't it ideal? But such a "pattern" is often set against a very gloomy background: neuroses, anxiety, "survivor's complex," fear, search for new waves of antisemitism, a sense of persecution, and the obligation to do unenjoyable work to make a living. Refined, bizarre, and stifling, Paul Celan did not cope well with the challenges he faced.

He seemed to be especially unsettled by public scandals and rejections. The worst incident was the so-called "Claire Goll affair." Starting from 1953, the widow of the French-German poet Yvan Goll accused Celan of plagiarism, i.e., "stealing" elements of her late husband's poems. Some journalists and critics picked up on these accusations, but literary circles generally supported Celan. The frivolity of Claire Goll's statements was generally known, but they came at a moment in Celan's life when his psyche was unstable (that year, he lost his first son) and evoked an extremely painful reaction. The Goll affair was even reflected in his poems, and he actively corresponded with friends to discuss it and receive serious support from them. Celan interpreted the scandal not only as a personal persecution but as another manifestation of antisemitism or even neo-Nazism. This case held Celan in its grip for years. In 1962, he attacked a passerby at a resort, yelling that he was linked to Goll. Celan's mental condition deteriorated.

He left and did not return

In his later period, Celan transitioned to utterly complex, incomprehensible, but still conceptual poetry. Associative connections became more opaque, the sources of his texts most surprising (such as news reports). Celan's late poetry is represented in Threadsuns and even more prominently in his last and posthumous books, such as Showpart, Lightduress, and Timestead.

Unfortunately, Celan's deteriorating mental condition traumatized not only the poet himself but also the people around him. The assault on a stranger on the street was not the last episode. He once attacked his wife, after which he moved out. Therapy was unhelpful. On an April night in 1970, Paul Celan left home and did not return; his body was later found in the Seine. It is assumed that he could have jumped into the water from the Mirabeau Bridge. Celan once translated Guillaume Apollinaire's classic poem about the bridge into German.

Paul Celan reading selected poems in German (with English translations, including two poems mentioned in this article: "Death Fugue" at 00:00 and "In Egypt" at 10:09)

Oleg Kotsarev

Oleg Kotsarev

Writer, journalist, essayist, and translator. His latest books are the novel People in Nests and the poetry collection Charlie Chaplin Square. Co-editor (with Yulia Stakhivska) of the anthology Ukrainian Avant-Garde Poetry (1910s–1930s).

Originally appeared in Ukrainian @Chytomo

Translated from the Ukrainian by Vasyl Starko.

This material is part of a special project supported by Encounter: The Ukrainian-Jewish Literary Prize. The prize is sponsored by the Ukrainian Jewish Encounter (UJE), a Canadian charitable non-profit organization, with the support of the NGO "Publishers Forum." UJE was founded in 2008 to strengthen and deepen relations between Ukrainians and Jews.