The poetry of Kateryna Babkina has been translated into Hebrew in Israel

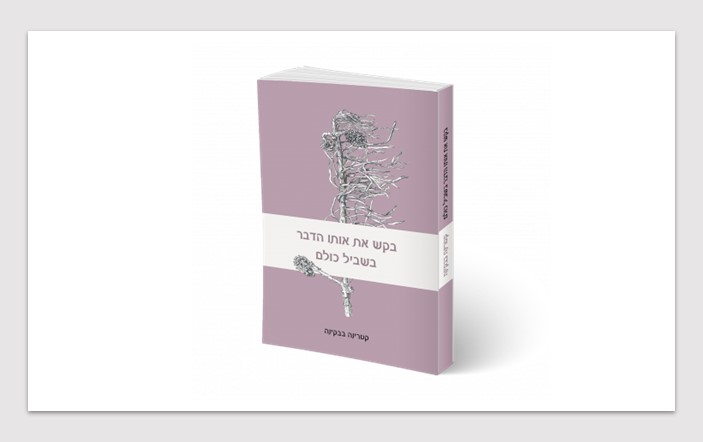

Kateryna Babkina’s poetry collection Dlia vsikh odnakove poprosy [Ask the Same for Everybody] will come out in June in a Hebrew translation published by the Israeli publishing house Khaver Laet.

Ms. Babkina talks about her new book on the program Encounters and her expectations of the launch of her poetry collection in Israel.

[A note to the readers: This interview was conducted and aired before the book’s publication in Israel.—Ed.]

Kateryna Babkina: Israeli readers can read my poetry collection in Hebrew, the title of which is derived from a line from one of my texts, “Ask the Same for Everybody”. This is a collection of poetry translated by Anton Paperny.

Most of these texts were written recently, so they turned out to be topical for listeners and poetry lovers in Israel. There is a lot in them about the sluggish pace of a military conflict against the background of the national life of an entire country, and this very topic has turned out to be rather similar to certain realities in Israel.

Iryna Slavinska: To what extent are the realities described in this collection relevant to Israeli readers?

Kateryna Babkina: As it turned out by chance during my readings that took place half a year ago, and which gave rise to this whole story, they are quite similar to each other; with similar and universal philosophical problems that I raise there, and the background. The mood and atmosphere that generate these various processes turned out to be unexpectedly similar and shared. The non-Ukrainian speaking people who were listening to me, that is, to the translations of my texts into Hebrew, asked me: “Why do you write so much about Israel?” And I told them: “This is not about Israel but about the Donbas.” And they reacted by saying, “Ah, of course!”

Iryna Slavinska: Let’s tell this story from the beginning. How do Ukrainian poets end up at poetry readings in Israel? How is a translator found? I want more of this back story, which is usually imperceptible to readers and our listeners.

Kateryna Babkina: There is an organization in Israel, called Israeli Friends of Ukraine. They are mainly Ukrainians who have lived in Israel for some time and they carry out charitable and volunteer work, such as collecting funds for medical treatment, helping children, adults, soldiers, and the like. These are people who, to put it roughly, accept patients of charitable foundations who are traveling there for treatment, or who send awesome bandages to the ATO. [Anti-Terrorist Operation, as the conflict in the Donbas is called—Ed.]

There is also a Ukrainian Embassy in Israel. The Ukrainian Jewish Encounter also works there. This is an international organization that is developing the exchanges between the Ukrainian and Jewish cultures, helping to establish contacts between contemporary Ukraine and Israel. And all this came together around my children’s book, Shapochka I kyt (A Hat and a Whale).

Iryna Slavinska: It should be mentioned here that A Hat and a Whale is a children’s book about the life a child with cancer. There is a significant altruistic component in this book: cooperation with the Tabletochka charitable fund.

Kateryna Babkina: Yes. So, together with the Cultural Department of the Ukrainian Embassy and the volunteers from Israeli Friends of Ukraine, it was decided to organize a reading for me in Bat Yam. Bat Yam is a city near Tel Aviv and Jerusalem, and there’s a Ukrainian Cultural Center there. And when I was ready to go there, we were discussing the topic of meetings, and there turned out to be more of them than we expected.

Together with the launch of the children’s book, we decided to organize a poetry evening as well. And then Anton Paperny wrote to me. It turned out that this person has been reading and translating my poetry into Hebrew for a long time, and he had already accumulated quite a number of these translations. I say: “Cool. I would like this to be heard.” But Anton Paperny lives far from Bat Yam. But his friend, who turned out to be the director of a not very large but cool publishing house agreed to come to Bat Yam… He agreed to come and be the one to simply voice this in Hebrew. That is what he did.

Already during the reading we unexpectedly discovered this reaction on the part of the Israeli audience. It turned out that everyone liked the texts very much. These are definitely very fine translations because people reacted to them in a very animated fashion. Secondly, my poems in Hebrew translation turned out to be unexpectedly close precisely to an Israeli audience. And that’s how the idea was born to publish a book of my poems in translation. Anton Paperny, the translator, said that he would gladly support this, and he was engaged to translate the texts into an entire book. The publication of the book was supported by the organization Ukrainian Jewish Encounter, and in fact this publisher received this grant for translation, and through a joint effort they published the book.

Iryna Slavinska: This is really an absolutely fantastic story about how literature travels and how sometimes a space appears, even for chance encounters that create this kind of product. I would also like to ask you a bit about the readers’ reactions. You say that the feedback was very palpable and that possibly it also influenced the decision of the publisher in Israel to publish this book. How did you perceive this feedback? Did people come up to ask something, or were there perhaps reactions during the reading itself?

Kateryna Babkina: There were reactions during the reading itself. You can see them with your own eyes. After the reading people also came up, and they talked about their impressions. And this was a really big surprise for me. I was struck by certain moments and how they understand them without comprehending the Ukrainian original. For example, they thought I was writing about Israel and they asked me why. It turns out that it was not entirely about Israel, but some things are truly very similar.

Iryna Slavinska: Next on the program Encounters, Kateryna Babkina reads the poem where one line provided the title of the collection that will be published in Israel.

…don’t forget to say something about those who are not dear to you at all,

who did not love or protect you, who did not help you to climb ashore,

And also ask for those who are zealously called enemies,

And, of course, for those who are wicked, weak, not like you want them to be, not like you.

You must also tell about those who are in the field, on the sea, in the orchard, at the cinema,

Who fell, jumped up, sat down, is lying down, who is going to kindergarten for the first time,

Who is burning in hell, who was baking a pie, who bought a suit, who broke a window,

Who said that he would do it, but could not, who did not know or see where.

Better call them by their names, so as not to lose track of their names—

The woman who to this day is the one and only, and the man who repairs the roof for us,

Who parks the wrong way every day, who settles down to sleep on the right side,

Who breaks the ice on the stairs in the winter, who disregarded fear, who fell in battles.

Above you burns a nightlight, it’s quiet in the room and outside.

You are now transparent, light, no one’s, smaller than insects, more delicate than dew—

Current, head out; walnut, grow; fly to the one who is above,

Don’t forget, don’t blunder, tell about everyone and ask for the same thing for everyone.

Iryna Slavinska: Is this a prayer?

Kateryna Babkina: No, it’s simply a poem. It’s an appeal to anyone who can soon turn directly to God, like that. That is, in principle, yes, in some sense it is an indirect conversation with God.

Iryna Slavinska: Who are these people? The ones who are going to kindergarten and those that you never even think about or absolutely do not appreciate?

Kateryna Babkina: Well, that’s absolutely all people. We must definitely ask for the same thing for everyone..

Iryna Slavinska: When you write about the large circle of people for whom it is necessary to make a request, whom do you have in mind? All people are, of course, all people, but they can be no one, too. In your mind, who are they? This intention to encompass the whole world—where does it come from?

Kateryna Babkina: In fact, the intention of this text is definitely to encompass oneself and resolve oneself internally once and for all; that ultimately everyone equally deserves to be forgiven, no matter what. In this case, this is surely an appeal to oneself and the dissemination of this thought, above all amidst oneself.

Iryna Slavinska: Next I would like to take a few steps back and continue the conversation about the reaction of Israeli readers, particularly to your poetry readings that took place a year ago. This was an opportunity for the readership in Israel to become acquainted with your texts in a translation into Hebrew for those who do not read Ukrainian. You say that there were many questions about the war, about why you write about Israel, and as a result you explained that this is not at all about Israel but about the war in the Donbas. Let’s begin from afar. In your poetic opinion, to what general extent is it natural for poetry to work with the topic of war?

Kateryna Babkina: It turned out, in my poetic opinion, that it is impossible not to work with it. It’s not that I am some sort of active participant in combat actions, and I don’t live near there, and I don’t spend very much time in Ukraine. But since all this began, somehow on the metaphorical level, on the atmospheric level, on the level of a direct topic, it squeezes into all the texts, into each text.

On the one hand, obviously on some superficial level, we grew accustomed to this very quickly and we adapted. We know that it simply exists and lives somewhere near us. But on the other, it turns out that it is a bit more alarming than we realize, because it is constantly revealing itself in precisely such things as writing, as creativity, and it is impossible not to talk about it. I never made any conscious decision to write social lyric poetry or poems about war, and subsequently this war is turning up everywhere.

Iryna Slavinska: If we are talking about the existence of the war theme, are we talking about a description of combat actions or are these things perhaps less mimetic than those that recreate some kind of reality to a lesser degree. What do they recreate?

Kateryna Babkina: They recreate the reality of people who are living next to this. There are no descriptions of combat actions because this is not some sort of epic lyrical poetry. Secondly, I did not take part in any kind of combat actions. There is much of what is the result of the war: the traumas that we experience, losses, fears, change of focus, displacement of the assemblage point. We had our own approach to life, and later these events shifted it a great deal for many of us.

And this is perhaps precisely what is so similar for Israeli readers because they have been living with this business for many years, and they are much more accustomed to this and adapted than we are. Let’s say they hear a siren, they hear a warning signal that a bombing is possible, and they don’t get up until they finish smoking their cigarette. Why? Simply because they are living with this. For them this is already normal reality, but, on the other hand, no, this is not normal reality. It changes you.

So, in many regards these texts are about the angle of the turning point, this change, the upheaval that is taking place thanks to society experiencing such things.

Iryna Slavinska: If we are talking about a feeling of anxiety, do you sense some kind of emotional changes in yourself, some new feelings, new thoughts, new anxieties?

Kateryna Babkina: You overestimate very many things. You begin to look differently at a lot of things. On the one hand, when you realize how close this is and how little in fact separates you geographically from what is happening. And one way or another, certainly every, every person our age has lost someone more or less close to them there in the east. And then you really understand that this is for real and that this is an immediate part of your life. This has a very big impact on you concretely. And it provides you with experience and places before your eyes the fact that in reality very many things influence your life, more than you are accustomed to keeping in your field of vision. And with such events it is no longer possible to forget about this. Now you always have these figures on your mind. In other words, you continue to have some strategic planning for your life, your development, but you write two and you have twenty-two on your mind. And there are various twenty-twos, but the main thing is that they are always there, and you are learning how to pay attention to them.

Iryna Slavinska: What experience of war in Ukraine and in Israel seems to you to be common, understandable for everyone? I mean for both countries, for all readers.

Kateryna Babkina: This is the tricky part, this is finiteness, in a sense this is ostensible non-involvement in it. Here in Kyiv, in the normal course of life, events that are located six hundred kilometers away have practically no impact on it in principle. In Israel, I think, six hundred kilometers is the longest distance that you can cover within the country. And in their country also war has become a part of daily life: some shooting here, something has been set on fire there, something has exploded there, something has flown in there. And the most terrible thing is when you become used to this. It is probably this experience of ours that is shared.

Iryna Slavinska: What experience have you noted as distinctive? After all, the war in Israel has combat actions, and the experience of regular terrorist threats. In Israel it is much more protracted than the Ukrainian experience, which emerged in our consciousness only in the spring of 2014.

Kateryna Babkina: In their country a more concrete line has been drawn of who against whom. One can speak concretely about the Jewish-Muslim, Jews against Arabs line of conflict.

Iryna Slavinska: Well, these too are labels.

Kateryna Babkina: These are certain labels, but they are nonetheless some kinds of identities. In our country, for example, this is more complex. For example, when I try to explain to a foreigner or to explain in general to myself, inside myself, what, for example, is happening there, who is fighting against whom…

Iryna Slavinska: Why? For example, the Russian army, which is on Ukrainian territory…

Kateryna Babkina: Without a doubt, the Russian army is there. We know this. But, on the other hand, we must constantly remind [people] about this and prove this, whereas Israeli society is not confronted with such a problem. Besides the Russian army, there is also quite a bunch of good people who—I must say this—are Ukrainians. And if everything ends sooner or later and the question arises of how to continue living with these Ukrainians. It is true, such a question exists, and there are many very incomprehensible things. One can understand now some root causes of these processes that are taking place there, but it is difficult to stop them; practically as difficult as pushing the Russian army out of there. In this conflict and that one I think there is also a commonality in that I see no end to it. I cannot say how it is supposed to end. But perhaps there are people who see it and know.

Iryna Slavinska: We asked Kateryna Babkina to read a poem from her eponymously titled Ukrainian book, the collection Zahovoreno na liubov [Enchanted for Love].

Here love has been enchanted. Here sage

sows itself right into the ground. And stormy and blue

nights, like sage, rustle beneath the winds of autumn.

Here in rivers the water becomes so unfathomable in the winter, sky-blue,

And trees whisper above rivers—their voices are dovish,

With sweetbrier echoes, silken and languid.

Here the steppe is covered with a dark sky, as an ocean

Covers golden, priceless sands;

And the earth, as though blood, thick and brown, is warm to the touch.

Here even missing obscurities become truly a fog,

With a healing haze they settle on the curves and crevices

Of wounded fields, exhausted, frozen in slumber.

Here life has been enchanted, and life, surprisingly,

nests in homes with children’s laughter, like foxes in dens,

With early cherry blossoms it covers gardens, where missiles have twisted the roots,

With little bluish clouds in the cold air it marks human breath.

Here love has been enchanted, for love—hear, not for fire and gunpowder,

Here it has been enchanted: death, don’t move, don’t let this enchantment stop.

Iryna Slavinska: Who is doing the enchanting?

Kateryna Babkina: I think someone cast a spell before our arrival.

Iryna Slavinska: And who is speaking? This is the eternal question of everyone who reads.

Kateryna Babkina: In their own way, everyone who lives this life leaves some kind of spell of their own; mostly, if everything is correct and there are no crookedness and malfunctions, then spells for life and for love, but not for something else.

Iryna Slavinska: When we read your text or, rather, hear in this case, who is uttering these words?

Kateryna Babkina: Who is the lyrical hero? Well, definitely someone who is left on this earth and remains there and is waiting until life and love dawns there again, not fire and gunpowder. Definitely someone like that, someone who desires this land, who loves this land, who wants simply to live there. Apples are growing, water is flowing. One would think: what else is necessary? But here some superfluous contexts appear, in their footsteps comes the Russian army as well as many other inconveniences. I would even say much unpleasantness.

Iryna Slavinska: Is this a post-apocalypse?

Kateryna Babkina: This is more of an anti-apocalypse. This is instead of an apocalypse.

Iryna Slavinska: So we end on an optimistic note.

Kateryna Babkina: I thought perhaps this is my most optimistic text.

This program was made possible by the Canadian non-profit organization Ukrainian Jewish Encounter.

Originally appeared in Ukrainian (Hromadske Radio podcast) here

Translated from the Ukrainian by Marta D. Olynyk.

Edited by Peter Bejger.

NOTE: The UJE does not necessarily endorse opinions expressed in articles and other materials published on its website and social media pages. Such materials are posted to promote discussion related to Ukrainian-Jewish interactions and relations. The website and social media pages will be places of information that reflect varied viewpoints.