Prominent Jews in the history of Kharkiv

Kharkiv is the second largest city in Ukraine. In 2024, as it fights off Russian aggression, Kharkiv marks the 370th anniversary of a Ukrainian Cossack fortress, its inception point. Jews have been an important, influential, and vibrant part of the city.

Kharkiv celebrates City Day on 23 August, and toward this date, I present an essay about twelve outstanding Jews who left a mark in its history.

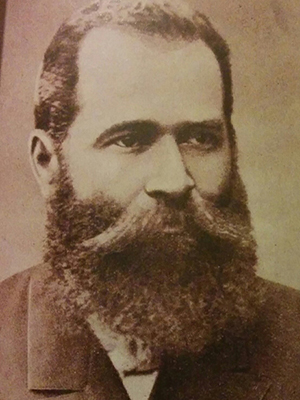

Peysakh Buras

Peysakh Buras

Peysakh Buras (1842–1914) was a merchant of the first guild and a philanthropist. He opened the Buras and Co. Tobacco Factory in Kharkiv in 1879. In the early 20th century, it was considered one of the best factories in the Russian Empire and its products were in high demand abroad.

Buras made efforts to improve working conditions for his employees and financed a suburban hospital for children suffering from lung diseases. He was one of the founders of Kharkiv's Society for Helping Poor Jews, a hospital, and an almshouse. He also sponsored the construction of the buildings of the Jewish charitable society and an educational institution.

Moisei Fabrikant

Moisei Fabrikant (1864–1951) was an outstanding surgeon and one of the fathers of plastic surgery in Ukraine. Upon graduation from Kharkiv University, he became a resident at his faculty's surgical clinic. After an internship abroad, he worked as a professor at the university clinic, starting in 1892, and had a private surgical hospital built for him.

In October 1941, Fabrikant, well advanced in years, did not want to leave Kharkiv, saying: "I know the Germans. They are cultured people, and many of my medical colleagues are among them." However, as one of the most valuable medical specialists, he was escorted to the last train leaving Kharkiv on personal orders from Nikita Khrushchev.

Fabrikant chaired the Head and Facial Surgery Department at the Kharkiv Medical Institute for many years. He worked there until 1950, retiring at age 86.

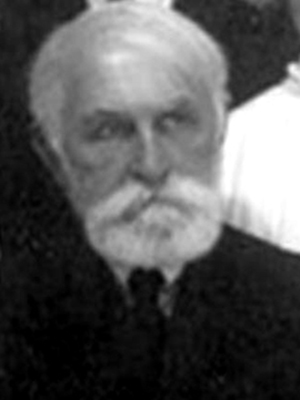

Ovsii Braunstein

Ovsii Braunstein (1864–1926) was an outstanding ophthalmologist and founder and leader of the Kharkiv Medical Society. Upon graduation from Kharkiv University in 1887, he worked there as a resident at the ophthalmology clinic. He was an assistant to Dr. Leonard Hirshman in 1893–95 and the owner of an eye clinic in Kharkiv from 1898.

A supporter of women's education, Braunstein was among the initiators of opening the Women's Medical Institute in Kharkiv. In 1924–26, he chaired the Department for Eye Diseases. Braunstein published studies on traumatic eye injuries, retinal detachment, trachoma treatment, and optic nerve diseases.

In the early 1900s, Braunstein was the head of the Kharkiv Zionist Committee, passionately advocating the creation of a Jewish state. The Kharkiv Zionist Conference, which he hosted in his house on Rymarska Street in November 1903, became a milestone event in the history of the State of Israel. The participants signed an ultimatum demanding that a future Jewish state be created only in the Land of Israel. This decision helped reject the so-called "Uganda plan" to set up a Jewish state in Africa.

Oleksandr Ginzburg

Oleksandr Ginzburg

Oleksandr Ginzburg (1876–1949) was a Ukrainian architect, academic figure, and founder of constructivism in architecture. He graduated from the Faculty of Mathematics of Kharkiv University in 1898 and from the engineering faculty of the Kharkiv Institute of Technology five years later. He then set up Zalizobeton, his own design bureau.

Ginzburg was a modernist and constructivist in architecture. For the first time in Kharkiv, he designed multistoried apartment buildings using reinforced concrete. He became actively engaged in industrial architecture in 1924 and taught at the Industrial Academy in 1933–38 and at the Industrial Institute from 1933 onwards.

Stalin's security agencies monitored Ginzburg in the late 1930s, planning to arrest him "for espionage on behalf of Germany." He managed to leave Kharkiv before the Nazis captured the city in 1941. Returning to Kharkiv in 1944, Ginzburg was shocked to learn of the brutal extermination of Kharkiv Jews by the Nazis. His colleague Viktor Estrovych, a prominent Ukrainian architect who worked in Kharkiv in the Renaissance Revival and Art Nouveau styles, was shot with his wife in Drobytsky Yar.

Ginzburg returned to his ethnic roots and was elected head of the city's Jewish community, which the Soviet authorities soon closed down. In 1945, he was stripped of all positions and banned from teaching. The authorities called his activities a harmful "manifestation of Zionism."

Ginzburg designed more than 120 buildings, 20 of which are included in Kharkiv's List of Architectural Monuments.

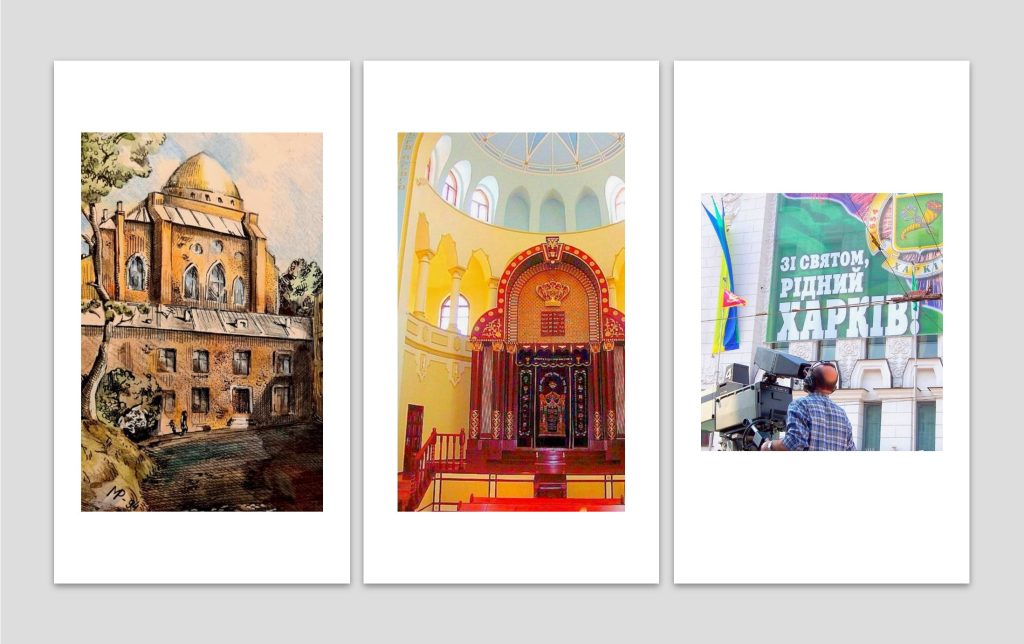

Aharon Tumarkin

Aharon Tumarkin (1885–1936) was a Lubavitch Hasid, the last rabbi of Kharkiv under totalitarian communist rule. He was the spiritual leader of Kharkiv's Jewish community from 1918 until his death in 1936, heading the synagogue on Chobotarska Street and the House of Learning attached to the synagogue.

The communist authorities closed the synagogue in 1932 and evicted the rabbi from his house to the outskirts of the city. Tumarkin's entire library of spiritual literature was destroyed.

In March 2022, two Russian rockets hit the roof and courtyard of the synagogue on Chobotarska Street, where Rabbi Tumarkin used to pray and teach.

Viktor Kogan-Yasny

Viktor Kogan-Yasny

Viktor Kogan-Yasny (1889–1958), MD, an outstanding Ukrainian doctor, professor, and Honored Scientist of the Ukrainian SSR (1941), graduated from the Medical Faculty of Kharkiv University in 1913. He was Associate Professor at the Therapy Department (from 1926), head of the Department for Internal Diseases of the Sanitary and Hygiene Faculty (1932–38), and head of the Hospital Therapy Department at the Kharkiv Medical Institute (1938–41, 1943–53).

Kogan-Yasny was the first in the USSR to develop insulin production, thus saving the lives of thousands of people who had diabetes. The author of 9 monographs and some 40 handbooks and textbooks, he was the chief therapist in the Ministry of Health of the Ukrainian SSR.

In 1930, an endocrinology clinic that included laboratories and specialized departments was opened in Kharkiv under the leadership of Kogan-Yasny, the first such institution in the USSR and the third in the world.

The security services arrested Kogan-Yasny in February 1953. They tortured him during interrogations to force him to confess alleged "links" with prominent medical scientists arrested in Moscow in connection with the "doctors' plot."

Kogan-Yasny was falsely accused by the local Communist Party committee and harassed in the Kharkiv Medical Institute. He was released from prison and returned to Kharkiv in April 1953, after Stalin's death.

Dmytro Klebanov

Dmytro Klebanov

Dmytro Klebanov (1907–87) was an outstanding Ukrainian composer. He was the conductor of the Kharkiv Theater of Musical Comedy in 1927–28 and the Kharkiv Radio Orchestra in 1931–34. He also taught at the Kharkiv Conservatory from 1934 onwards, becoming a professor in 1960.

Klebanov became the head of the Department of Composition and Instrumentation at the Institute of Arts in 1970. He wrote the textbook The Art of Instrumentation (1972) and mentored many Ukrainian composers.

Klebanov composed the Ukrainian Concertino (1940) and the Ukrainian Suite (1949) and cycles of songs to the poetry of Taras Shevchenko. He received the Honored Artist of the Ukrainian SSR distinction in 1967.

In 1945, Klebanov wrote a symphony dedicated to the victims of the Babyn Yar massacre, raising the topic of the extermination of Jews by the Nazis during the Holocaust for the first time in the USSR. For this, he was accused of "cosmopolitanism" and Jewish nationalism in 1948–49.

Klebanov was harassed in the Union of Composers and dismissed from all posts. The composer was able to return to his work only after Stalin's death. His symphony Babyn Yar was performed in Ukraine for the first time in 1990.

Mark Azbel

Mark Azbel

Mark Azbel (1932–2020) was an outstanding physicist, dissident, and organizer of scientists resisting the Soviet totalitarian regime.

He graduated from Kharkiv University in 1953. At age 23, Azbel predicted cyclotron resonance in metals (Azbel-Kaner cyclotron resonance), defended his candidate's thesis under the guidance of Professor Ilya Lifshits, and began working at the Kharkiv Physical and Technical Institute.

He became a section chair at the Institute for Theoretical Physics in Moscow but was dismissed from all posts after he applied for emigration to Israel in 1972.

After he was refused exit permission, Azbel launched a struggle against the regime. For the first time in the USSR, he created an international scientific seminar for scientists who were denied permission to emigrate. In 1977, the KGB allowed him to leave, and Azbel chaired the Department for Theoretical Physics at Tel Aviv University. He won the Israeli Landau Prize in 1989.

In an interview given in Israel, Professor Azbel said: "As I completed school education [in Kharkiv], I firmly knew that I hated this system, the party, the government, and the leader. Having received an invitation to work under Kurchatov, I decided I didn't want to give weapons to such authorities. It was one of the smartest things I've done in my life."

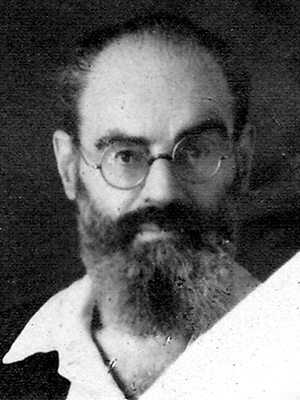

Gershon Drinfeld

Gershon Drinfeld (1908–2000) was a professor of mathematics and a founder of the Kharkiv School of Mathematics. He was the deputy director of the Kharkiv Institute of Mathematics in 1944–50.

Drinfeld's library became a mathematical literature office of the Mechanics and Mathematics Faculty of Kharkiv State University and one of the best mathematical libraries in Ukraine.

Drinfeld chaired the Department of Mathematical Analysis at Kharkiv State University in 1944–62 and made a fundamental contribution to teaching mathematical analysis, raising a group of outstanding Ukrainian mathematicians.

During the antisemitic campaign of 1952–53, the communist authorities planned to accuse Drinfeld of "poor teaching," but not a single student would support this accusation.

Moisei Fradkin

Moisei Fradkin (1904–74) was an outstanding Ukrainian graphic artist and a classic figure in children's book illustration. He graduated from the Kharkiv Arts Institute in 1927 and taught as an associate professor there from 1931 to 1971.

Fradkin illustrated many Ukrainian children's books, Jewish Folk Songs, and selected works by Sholem Aleichem. Fradkin's works are kept in the Kyiv State Museum of Ukrainian Art, the Kharkiv Museum of Fine Arts, and national galleries in Stockholm and Chicago.

Yakiv Eisenberg

Yakiv Eisenberg (1934–2004) was a Ukrainian scientist and the leading theorist of four generations of control systems for rocket and space technology. He was an Honored Worker of Science and Technology of Ukraine, professor, and academician.

Eisenberg graduated from the Radio Engineering Faculty of the Kharkiv Polytechnic Institute in 1956 and became the chief designer and CEO of the Hartron plant in 1990. His most famous projects included the launches of the SS-18 "Satana" strategic rocket, the super-heavy Energia launch vehicle, and the creation and launch of the Zorya functional cargo unit, which marked the beginning of the International Space Station.

Eisenberg was a member of the International Academy of Astronautics (IAA) and the US Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE).

Boris Elkin

Boris Elkin

Borys Elkin (1947–2011) was an outstanding scientist, professor, and educator. After graduating from Kharkiv State University with honors in 1970, he worked there at the Mechanics and Mathematics Faculty until 1995, rising to deputy dean for science.

He was the author of more than 150 scientific works, inventions, and state standards in radiometry and photometry. Elkin's math results are still used in space programs, and his catalysts for oil and dirty liquids work at Ukrainian oil and coke plants and Kryvorizhstal.

Elkin founded the Eastern Ukrainian branch of the International Solomon University (1998–2011) and created the Center of Jewish Studies and the Center of Khazarian Studies, which conducted expeditions and research on the history of Eastern Europe.

His son, Zeev Elkin, is a well-known Israeli politician, ex-minister, member of the Knesset, and co-chairman of the Israel-Ukraine parliamentary group.

Afterword

In a short essay, there is not enough space to mention all the outstanding Jews associated with Kharkiv. For example, brothers Ephraim and Nahum Loyters created and managed the State Jewish Yiddish Theater in Kharkiv in the 1920s and 1930s.

There were rabbis, the promoters of Judaism, and communist Jews, the persecutors of this religion. There were Jews who headed NKVD punitive bodies and their Jewish victims, such as the executed poet Benzion Fradkin, the author of the last book of Hebrew poems published in the USSR.

All three Nobel laureates who studied or worked in Kharkiv were Jews: Ilya Mechnikov (physiology), Lev Landau (physics), and Simon Kuznets (economics).

Academician Serhii Bernstein founded and directed the Ukrainian Institute of Mathematical Sciences in Kharkiv. Brothers Naum and Oleksandr Akhiezers, who worked in Kharkiv for decades, founded entire scientific schools in mathematics and physics. Academicians Yevhen and Ilya Lifshitses made a huge contribution to the development of physics.

It may seem to some that the most famous Jew in the history of Kharkiv is Hennadiy Kernes, the city's controversial mayor in 2010–2020, although I do not think so.

For Kharkiv, Jews are not only its past but also its present. Present-day Kharkiv, which has been steadfastly withstanding the barbaric attacks of Russian aggressors for the third year now, has several prominent Jewish personalities.

One is Rabbi Moshe Moskovitz of Kharkiv, who did not leave the community and the city during the most difficult period of the war. He provides humanitarian aid to all residents of Kharkiv regardless of their ethnic background. Under his leadership, the Choral Synagogue became a shelter, a center of invincibility, and a place of hope for hundreds of Kharkiv residents.

Oleksandr Feldman is a businessman, philanthropist, and member of Ukraine's parliament. His Feldman Ecopark on the outskirts of the city was damaged in the first months of the Russian invasion. Some of the employees and animals were killed, and many premises were destroyed.

Maksym Rosenfeld is a designer, regional ethnographer, and creator of films about Kharkiv's history and modernity. He fills tens of thousands of Kharkiv residents with optimism. Rosenfeld develops and popularizes the "spirit of the city," which is the foundation of Kharkiv's mental matrix: freedom on the frontier's edge, resilience, and creativity.

The way Feldman is currently restoring his Ecopark and the new senses Rosenfeld has found for the survival and development of Kharkiv in the new era fill its residents with strength and hope for a quick return to peaceful life after the war.

Text: Shimon Briman (Israel).

Translated from the Ukrainian by Vasyl Starko.