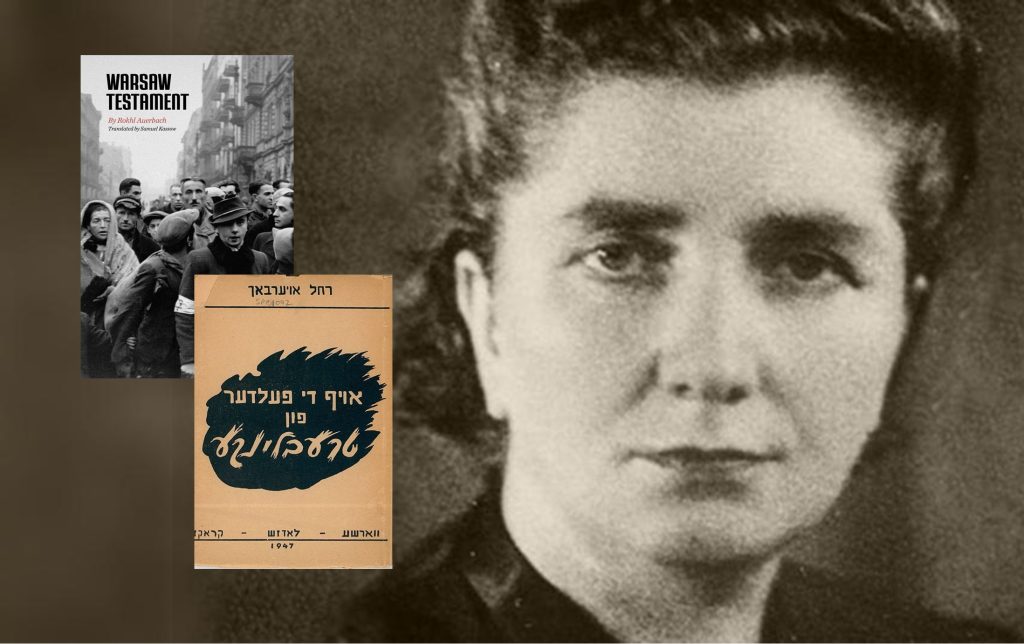

Rokhl Auerbakh (1903-1976)

Rokhl Auerbakh is one of those women who had a tremendous impact on the history of the 20th century. She was born into the Jewish family of Khanin Auerbakh and his wife Mania (née Kimelman) in the small town of Lanivtsi (now in Ternopil Oblast) in December 1903 in what was then the borderlands of the Russian Empire. Later, the family moved to Lviv, where Rokhl studied at the Adam Mickiewicz Gymnasium and later completed philosophy and general history studies at the Jan Kazimierz University.

The young and purposeful Auerbakh became particularly active during this period. In 1925, she began her writing career as a journalist for the Polish Zionist daily Chwila, later joining the Morgen Yiddish daily as an editor. In the late 1920s, Auerbakh also edited a literary column in a weekly published by Poalei Zion. In general, she worked for many periodicals during this period. For example, she was an editor of Tsushtayer, a popular Yiddish literary magazine, and a co-editor and co-author of Yidish, a journal about the cultural movement in Galicia.

In 1933, Auerbakh moved to Warsaw, where she continued her active editorial and journalistic activities, contributing to the leading Yiddish and Polish newspapers and literary journals of the time. Meanwhile, the 1930s became a severe test for her, as her only brother died in 1935, soon followed by her parents. The Second World War found her in Warsaw, where she ended up in the ghetto under the German occupation.

Auerbakh joined the secret Oyneg Shabes group organized by Emanuel Ringelblum during that extremely difficult time. The group's members became chroniclers, recording daily life in the ghetto and hiding manuscripts underground. Auerbakh kept a diary in Polish and recorded her experiences in the account titled "Two Years in the Ghetto," which described in great detail the widespread hunger she witnessed.

On 9 March 1943, Auerbakh managed to escape from the Warsaw Ghetto to the Aryan side. She secretly continued her diary, recording what she saw. She wrote prolifically as a chronicler, documenting life during the Holocaust. Only three people, including Auerbakh, from the once-large Oyneg Shabes group lived to see the end of the Second World War. Emanuel Ringelblum, who launched the group, died together with his family, just like the other members. Auerbakh initiated the excavation of the Oyneg Shabes group's manuscripts in post-war Warsaw, and they became extremely valuable historical documents of the 20th century, laying the foundation for the Holocaust chronicles and testimonies in Warsaw and Central and Eastern Europe.

Auerbakh worked at the Jewish Historical Institute in Warsaw from 1945 to 1950, recording, among other things, the testimonies of Treblinka extermination camp survivors. She co-authored guidelines for collecting testimonies and began publishing them in Polish and Yiddish. She emigrated to Israel in the early 1950s and settled in Tel Aviv.

In 1954, Auerbakh began her work as the director of the Testimony Collection Department at Yad Vashem and compiled a massive database by interviewing Holocaust survivors. Through this painstaking activity, she developed new methods for collecting testimonies and educated a new generation of Holocaust archivists and researchers. Auerbakh continued to publish texts about Jewish cultural life before and during the Holocaust in her native Polish and Yiddish, as Hebrew was difficult for her. Her tireless work produced part of the documentary evidence for the Adolf Eichmann trial in 1961, where she personally testified about life in the Warsaw Ghetto. The department Auerbakh headed collected over 3,000 testimonies in about 15 languages by 1965. She continued her active and often stressful activities at Yad Vashem until 1968, after which she retired.

Auerbakh's personal life was not tranquil, either. She was never officially married. In prewar Warsaw, she became close to the Jewish poet Itsyk Manger, a native of Chernivtsi. She was an inspiration for him and managed to rescue his archive during the Holocaust, returning it to him in London after the war ended.

Auerbakh's health became fragile as she approached 70. She was diagnosed with breast cancer in 1972 and underwent treatment three years later due to a recurrence of the disease, but she was not destined to live much longer. Rokhl Auerbakh died on 31 May 1976 at the age of 72. She bequeathed her estate to Yad Vashem.