Russian Jewish author chronicles wartime horrors in Austrian-ruled Galicia

“I saw that that the windows of these ruined houses were stuffed with rags or boarded up. In these unheated kennels were human beings, whole families, starving, usually sick because all kinds of epidemics were raging…”

One hundred years a bitter war was raging throughout Europe. One of the most devastated regions was the borderland of Galicia. Here the massive armies of Tsarist Russia clashed with those of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and Imperial Germany. The front surged back and forth. Refugees streamed in all directions. Towns were looted and burned to the ground. Villagers were taken hostage. Exiled. Lynched. And raped.

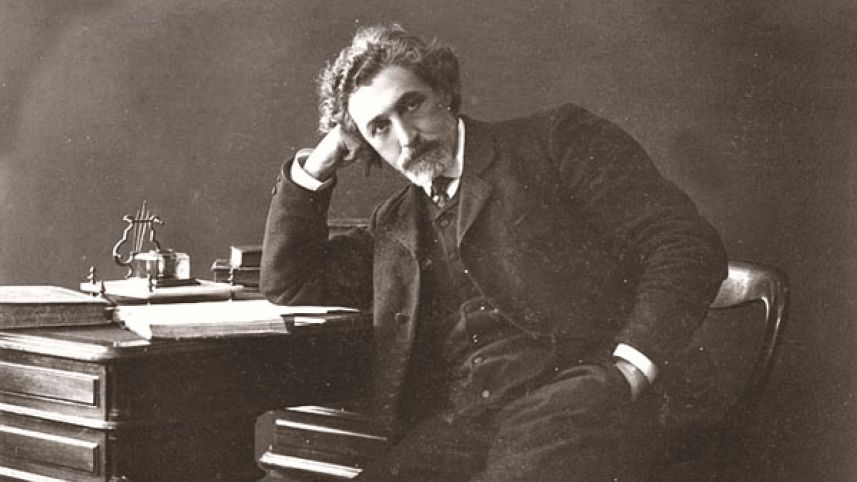

Into this devastation the influential Jewish-Russian writer S. Ansky was sent to organize relief for devastated Jewish communities. Ansky, born Shloyme Zanvel ben-Aaron Rappaport in Belarus, lived from 1863 to 1920. He is best known for his classic drama The Dybbuk. One of Ansky’s greatest contributions was the archive of Jewish folklore he collected during ethnographic expeditions in the Pale of Settlement before the First World War. These songs, stories, and superstitions recorded a culture already on the brink. A culture hit by the forces of emigration, persecution, and modernity. And now war.

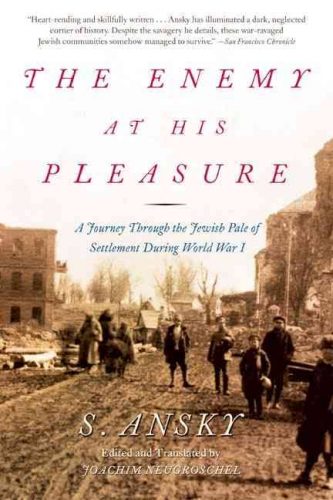

Ansky maneuvered through a treacherous terrain in wartime Galicia during his relief work. His harrowing experiences were detailed in the Yiddish-language book The Destruction of Galicia published after his death. The book is available in English under the title The Enemy at His Pleasure.

Ansky maneuvered through a treacherous terrain in wartime Galicia during his relief work. His harrowing experiences were detailed in the Yiddish-language book The Destruction of Galicia published after his death. The book is available in English under the title The Enemy at His Pleasure.

Ansky was a citizen of a Russian Empire that was often capriciously brutal to Jews and other minorities. The Russian army brought along this brutality when marching into Austrian-ruled Galicia. There it faced a complex ethnic and political situation. Galician Jews under Austria had enjoyed civil equality. Two very different worlds collided. Ansky saw that Galician Jews had a cult-like dedication to the old Austrian Kaiser Franz Joseph. But everyone had to navigate among other groups. The politically dominant German speakers, the Poles, or the Ruthenians, as the Ukrainians were then called, had their own conflicting agendas.

Ansky observed, “At the start of the war, Austria’s Poles were in an ambiguous position, while the Ruthenians stood apart from everyone. The Galician Jews, however, stuck to their pro-Austrian orientation, flaunting it in the most delicate of circumstances, with no concern for horrible consequences.”

The consequences were bleak, and Ansky’s sharply observant reports detailed how the people of Galicia “had lost the supreme sanctity of human dignity.”

“Packed military trains dashed by every few minutes…. Now a medical train flew by. In every window you could see bandaged heads, hands, and other parts of the body…. Next, a freight train stuffed with prisoners… Long, long trains, one after another, kept lumbering by, carrying Ruthenian refugees, most women and children. The passengers were crammed together like chickens in a cage. Some cars were packed with schoolboys, others with intellectuals. No baggage, no belongings were to be seen.”

After bearing witness to the devastation, Ansky was affected by a form of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. He described one visit to Russian-occupied Chernivtsi, which he called “an oasis in the wasteland.”

“Riding through the wide, bustling streets, I saw large boutiques filled with all sorts of elegant articles, the rich edifices, the hotels with their good, clean rooms, the posters announcing soirees, concerts, spectacles, and other entertainments. I felt spirited away to a different world. And yet I experienced a strange and horrible sensation: I caught myself longing for the burned, mutilated homes and stores. My eyes looked for them. And the houses with windows, the open boutiques, the calm streets—all this everyday life struck me as abnormal…. Later on, I learned that veterans of battle, who have seen corpses, maimed bodies, and rivers of blood, yearn for these things. Ordinary life seems pale to them without the cannon, without the shrieks….”

Galicia’s torment ended when a demoralized Russian army retreated in a wave of violence before it collapsed, as Ansky writes, “in the storm of revolution.”

In describing the aftermath, Ansky reached back to ancient legends. “When Moses returned with the tablets of the Decalogue, he was so horrified at the sight of the Jews worshipping the Golden Calf that he broke the Ten Commandments to bits… When the Romans, destroying the Temple, set the Scolls of the Law on fire, the letters of the holy script supposedly flew to the heavens from the burned parchment. These two symbols, ‘shattered tablets’ and ‘flying letters’ summed up the life of the Galician Jews.”

The Enemy at His Pleasure by S. Ansky, edited and translated by Joachim Neugroschel, was published by Henry Holt and Company and is available from online booksellers.

This has been Ukrainian Jewish Heritage on Nash Holos Ukrainian Roots Radio. From San Francisco, I’m Peter Bejger. Until next time, shalom!

Written and narrated by Peter Bejger.

Listen to the program here.

Ukrainian Jewish Heritage is brought to you by the Ukrainian Jewish Encounter (UJE), a privately funded multinational organization whose goal is to promote mutual understanding between Ukrainians and Jews. Transcripts and audio files of this and earlier broadcasts of Ukrainian Jewish Heritage are available at the UJE website and the Nash Holos website.

NOTE: The UJE does not necessarily endorse opinions expressed in articles and other materials published on its website and social media pages. Such materials are posted to promote discussion related to Ukrainian-Jewish interactions and relations. The website and social media pages will be places of information that reflect varied viewpoints.