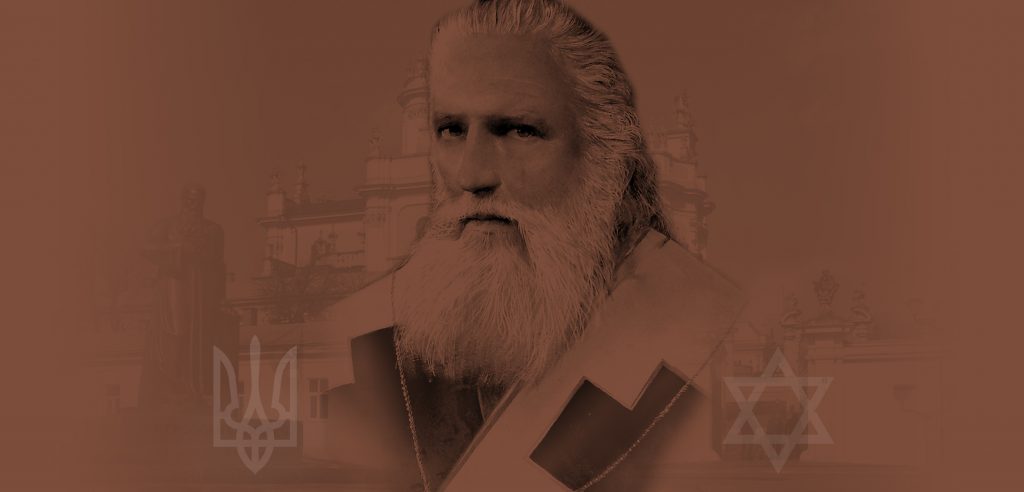

Saved by Sheptytsky

“No harm will come to you here."

Lilly Pohlman says she will remember these words till the end of her days. Along with the memory of a giant of a man gently reassuring her during the horror of Nazi brutality in the Second World War.

Over 150 other Jews who survived the Holocaust in Ukraine have similar memories. Three of them—Pohlman, Oded Amaranth, and Dr. Leon Chameides—share their personal recollections of that gentle giant, Metropolitan Archbishop Andrei Count Sheptytsky, in the documentary film Saved by Sheptytsky.

In just twenty-four minutes, this film delivers a poignant and powerful message.

Defying extreme danger, Sheptytsky used the administrative structure of the Ukrainian Greek-Catholic Church to cleverly defy the Nazis. Over 240 Ukrainian priests and nuns risked their lives hiding Jewish children, including in monasteries throughout the territory that makes up today’s western Ukraine. Metropolitan Sheptytsky himself sheltered fifteen Jews, including a rabbi, in his own residence at St. George’s Cathedral in Lviv. Because of the metropolitan’s actions, over 150 Jewish children were saved during the Holocaust.

Lilly Pohlman points out that Metropolitan Sheptytsky was the only church hierarch who protected Jews from the Nazis. She and fellow survivor Chameides both recall the Talmud quote. “Whosoever saves one life saves the entire world.”

Raya Shadursky, Director of Operations for the Ukrainian Jewish Encounter who is also one of the film’s scriptwriters and producers, said the driving force in making the film was to ensure history remembered the metropolitan’s actions.

“We wanted to make sure we could document those who were still alive who were saved by Sheptytsky, and to document them for public archives, not just ours,” she said. “This underscores the sacrifice Metropolitan Sheptytsky took to save more than 150 Jewish children.”

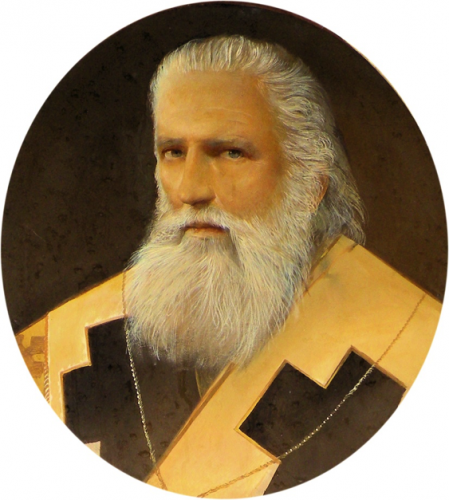

Metropolitan Andrei Sheptytskyi*

Metropolitan-Archbishop Andrei Sheptytskyi was a distinguished civic activist and cultural figure. But, most importantly, he was a committed Christian and church hierarch who came to be viewed by his flock as a leader of patriarchal stature. His career, which spanned most of the first half of the twentieth century, unfolded in a historic territory called Galicia, located in the heart of central Europe. Galicia was a multicultural land of several peoples, in particular of Ukrainians, Poles, and Jews. During Sheptytskyi’s lifetime it was ruled by no less than five states: Habsburg Austria-Hungary, the West Ukrainian National Republic, Poland, Nazi Germany, and Soviet Ukraine within the framework of the Soviet Union.

Sheptytskyi was born on 29 July 1865 on his family’s estate in the village of Prylbychi, which today is in Ukraine, very near the border with Poland. The Sheptytskyis had been a family of Ruthenian/Ukrainian nobles, who in the eighteenth century became polonized. The future metropolitan, named at birth Roman, was raised as a Roman Catholic Polish aristocratic subject of the Habsburg Empire. When he reached the age of twenty, Roman decided to return to the church of his ancestors. He adopted the Byzantine (Greek) rite of the Catholic Church, entered a Basilian Monastery, and chose as his new Christian name, Andrei.

After being awarded doctorates in law and theology, Father Andrei was ordained to the priesthood (1892) and, thereafter, rose quickly through the ranks of the Greek Catholic Church: as superior of two monasteries, as seminary professor, and as diocesan bishop. In 1900, Rome appointed him archbishop of L’viv and metropolitan of Galicia. Andrei Sheptytskyi was to lead the Greek Catholic Church for nearly the next half century, a period marked by two brutal world wars and the destruction of all the states which for a time had ruled Galicia. The frequent foreign invasions, changes of regime, and underground movements opposed to the ruling states all had a profound impact on the metropolitan. He experienced arrest, exile, and harsh criticism for what some thought were his politically unrealistic and pacifistic policies, on the one hand, or his overly accommodationist attitudes, on the other.

Throughout these turbulent decades, Metropolitan Sheptytskyi consistently defended the religious, social, civic, and national interests of his ethnic Ukrainian flock. These efforts took several forms: promotion of Ukrainian scholar-ship and education, opposition to anti-Ukrainian measures in Polish-ruled Galicia, establishment of a modern health clinic and museum of folk and religious artifacts, rapprochement with the Eastern Orthodox Christian world, and support for Ukrainian governments struggling for independence at the close of World War I and then again in the early years of World War II.

Despite his sympathy for Ukrainian political aspirations, Metropolitan Sheptytskyi never lost sight of basic moral principles and the sanctity of life. Therefore, he condemned politically inspired assassinations carried out in the name of the Ukrainian national cause—whether the victims were Habsburg Austrian and Polish officials, or Ukrainian activists killed by other Ukrainians. During World War II, and at great personal risk, he criticized the Nazi German rulers of Galicia and those among his own Christian flock who committed or condoned what he called “political murder,” in particular the murder of Jews. He called on his community to respect the commandment “Thou Shalt Not Kill,” which he linked with the precept, “Thou Shalt Love Thy Neighbor as Thyself.” Acting on what he asked of others, Sheptytskyi sheltered Jews personally and arranged for Greek Catholic monasteries to protect hundreds of Jewish children, many of whom survived the war and Holocaust to tell their stories of appreciation for the extraordinary actions of the metropolitan.

As World War II drew to a close and German armies were retreating, Soviet forces arrived in Galicia in the summer of 1944. The aged and by then infirm metropolitan did his best to defend the Greek Catholic Church against the increasingly restrictive measures imposed on it by the new Soviet regime. Metropolitan Sheptytskyi feared the worse—the destruction of his church—although he was spared from witnessing what in a few years did, indeed, become the church’s destruction and forced descent into the underground. He was spared from having to witness this tragedy, because he died peacefully in his sleep at the metropolitan’s residence in L’viv on 1 November 1944.

In the more than half a century since his passing, the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church has been restored and Sheptytskyi’s admirers, both Christian and non-Christian, have been urging the Vatican to beatify him—the first step in the process of declaring him a saint. As the cause for his beatification as well as for his recognition by Israel’s Yad Vashem as one of the Righteous among Nations continues, we are privileged to honour and to draw moral inspiration from the legacy, in the words of one Holocaust survivor, of “this spiritual giant”— Metropolitan Andrei Sheptytskyi.

Professor Paul Robert Magocsi, FRSC

Chair of Ukrainian Studies

University of Toronto

*Sheptytsky