Saving treasures from perdition

How Germany contributes to preserving Ukraine's Jewish heritage

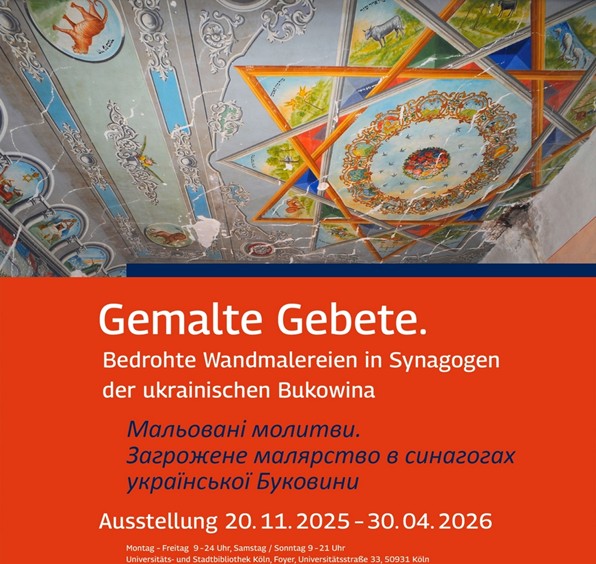

"I am impressed by the level of involvement of German specialists in our project to preserve Ukraine's Jewish heritage," said Yevhen Kotlyar, a professor at the Kharkiv State Academy of Design and Art, after the opening of an exhibition of synagogue murals from Bukovyna at the Cologne City Library.

He says the idea for this exhibition originated from German colleagues in response to the aggression against Ukraine, especially after the 7 October 2023 tragedy in Israel.

Synagogue murals created before the Holocaust still exist in only a few cities across Ukraine — and all these pieces of religious art face the threat of destruction and loss.

"We are saving what remains. We are preserving, at least through digitization, the potential for restoration in the future after the war [ends] in Ukraine," Prof. Kotlyar said in an interview.

The initiator and sponsor of this project is the Ukraine Art Aid Center (UAAC), a German nonprofit organization dedicated to protecting and preserving Ukrainian cultural heritage. UAAC is a network of cultural professionals and institutions, mainly from Germany, Switzerland, Austria, and Ukraine, formed in spring 2022 to support Ukrainian cultural institutions during Russia's invasion of the country.

Previously, this center held an exhibition in Germany about the wooden churches of Ukraine.

The working group focused on the art of Bukovyna's synagogues includes Kilian Heck, Jörg Haspel, Stephan Hoppe, Yevhen Kotlyar, and Mykola Kushnir. The exhibition curator is Prof. Aleksandra Lipińska (University of Cologne).

The Ukrainian company Skeiron carried out the technical work to digitize three synagogues in Bukovyna. Since the beginning of 2022, Skeiron has been digitizing Ukrainian landmarks at risk of disappearing due to Russia's war against Ukraine.

Skeiron specialists digitized two buildings in Chernivtsi and one in Novoselytsia, a city in the Chernivtsi region. They conducted a 3D laser scan and documented architectural and artistic details.

Based on laser scanning of synagogues by the Ukrainian company Skeiron, specialists from the Institute of Architecture at Mainz University of Applied Sciences developed an animated 3D model of the synagogue in Novoselytsia, which is a special highlight of the exhibition, demonstrating the modern possibilities of using digital technologies for documenting and presenting cultural heritage.

Objects from Chernivtsi and Novoselytsia displayed at the exhibition are:

- Groise Shil Synagogue was constructed from 1799 to 1854. It was considered the main synagogue of Chernivtsi until 1877. In the fall of 1941 through the winter of 1942, the building was part of the Jewish ghetto. Since 1959, the synagogue premises have been transferred to the city council for use as a cinema. Since then, the synagogue building has not been used for its original purpose.

- The Beit-Tfila Benyamin Synagoguewas built in 1923. Around 1938, the interior walls of the synagogue were decorated with murals. In the fall of 1941 through the winter of 1942, the religious building was part of the Jewish ghetto. After 1945, the synagogue became one of three synagogues in the city, with its operation permitted by the Soviet authorities. From the 1960s to the 1980s, it was the only one in the town. Official services resumed in 1994.

- The Novoselytsia Synagogue was built in 1919 when about 5,000 Jews lived in the city. After the Holocaust, Jewish religious life in Novoselytsia declined. The empty synagogue was converted into the Pioneer House, which remained there until the early 1990s. Since then, the building has been vacant. In 2009, wall paintings were discovered in the former synagogue by restorers from Kyiv.

A characteristic feature of most local synagogues is their intricate decoration, which combines prominent Jewish religious themes with the traditions of European palace art. This stems from Bukovyna's long history as a crossroads of nations, making it open to various cultural influences.

Prof. Kotlyar believes these are more than just pictures — they serve as a visual dialogue between Jews and the Creator.

One characteristic of the paintings in Bukovyna's synagogues is that they have been better preserved than those in other parts of Ukraine. The frescoes include many biblical themes, some of which are unique and not found elsewhere.

"We see a clear local artistic tradition, which is expressed in the folklore stylistics of the folk masters of Bukovyna," Professor Kotlyar said.

Sacred subjects are depicted in the synagogues of Bukovyna through local motifs and images contemporary to the artists and worshippers.

For example, the walls of Jericho were painted to resemble the Khotyn Fortress.

The symbol of the Tribe of Issachar — the "bony donkey" in the Torah — is shown as a cute donkey pulling a typical Bukovynian cart filled with books. The symbol of the Tribe of Zvulun — a ship — is depicted as a 19th-century-style steamer with a chimney.

The fresco, featuring a quote from Psalm 137 about the Jewish exiles in the rivers of Babylon hanging their harps on trees, depicts all the typical musical instruments of a Bukovynian klezmer band.

Jerusalem is depicted in the fresco in Chernivtsi almost as a joke: at the center of the painting is a large, dome-shaped building that resembles the ancient Jewish Temple in Jerusalem. However, it is actually the Christian Church of the Holy Sepulchre, and the artist painted the Star of David on its dome. According to Professor Kotlyar, the unknown artist, who clearly had not visited Jerusalem himself, simply copied the cityscape from a postcard brought by pilgrims from the Holy Land.

Even at the beginning of the 20th century, there were no images of people in the Bukovyna synagogue paintings, which shows the preservation of an ancient Jewish tradition. If the fresco depicts the parting of the Red Sea during the Jews' Exodus from Egypt, then in the painting, we only see Moses' hand, pointing his staff toward the sea.

"But now the remains of these artistic treasures are disappearing before our eyes," said Professor Kotlyar with sadness. "I opened the exhibition in Cologne with a very strange feeling that I was at the epicenter of a huge tragedy. Shortly before the exhibition, a Russian missile strike damaged my stained-glass windows in the synagogue in Podil, Kyiv. Then we learned about the arson of the synagogue in Sadygur near Chernivtsi, which had been under restoration for 20 years. On the same days, a Russian guided bomb destroyed dozens of graves in the Jewish cemetery in Kharkiv, where my ancestors are buried," said the Ukrainian scholar.

The German organizers of the exhibition in Cologne say it is a big success and has generated significant interest among visitors. Many people say, "We had no idea about this incredibly rich Jewish heritage of Ukraine."

Building on the success, plans are underway to expand the exhibition of Bukovyna synagogue art to other German cities in 2026, including Düsseldorf, Munich, and Berlin.

Text: Shimon Briman (Israel).

Photos from the exhibition: Yevhen Kotlyar.

Photos of synagogue paintings: from the official website of the Skeiron company.