Scar of war: Jewish memory of a childhood in Ukraine

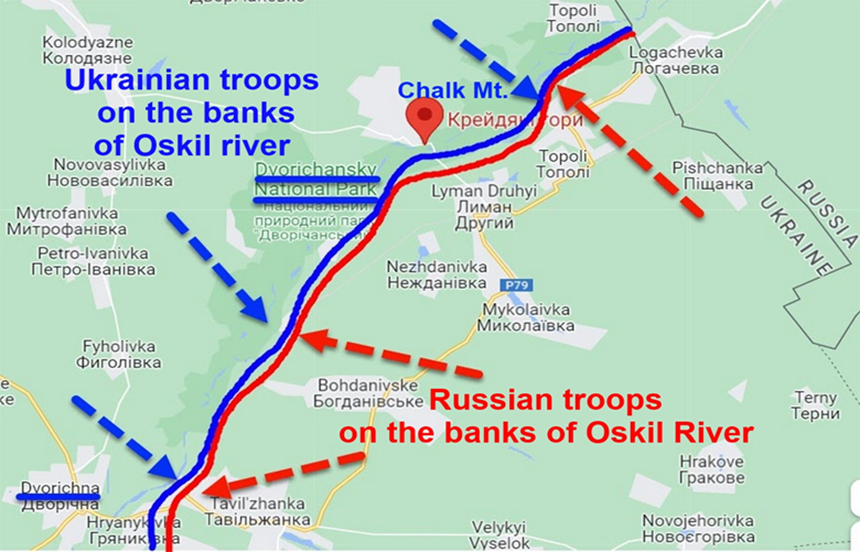

For six years, from 1980-1985, I spent July in a sports camp near the village of Dvorichna in the Kharkiv region. Now, the northernmost and last 30-kilometer section of the bleeding front in the Russian-Ukrainian war begins from Dvorichna.

In those last years of the Soviet Union, a thin Jewish boy who loved reading moved from the comfort of the city to the wild forests on the Oskil River. Life in tents, intensive training, swimming in a cold river, mosquitoes, and freedom from propaganda — no "young pioneers," no red ties and red flags.

We broke hazel branches, tied fishing lines, hooks, and bobbers to sticks, dug worms, and spent hours fishing. One day, my friend and I sat with fishing rods and saw how a giant wild boar emerged from the thicket on the opposite bank of the Oskil. He swam right at us, causing us to run away screaming.

Now, not wild boars, but sabotage and reconnaissance groups swim from the banks of the Oskil.

From the news of Ukraine, 2 March 2023: "Dvorichna is located in the zone of active hostilities, constantly fired from tanks, mortars, S-300 missile systems. There are no more undamaged houses left. Less than a third of the 3,500 inhabitants remained."

July 2024: "Artillery duels along the front on the Oskil River. The nearly destroyed Dvorichna again came under mortar fire from the occupiers."

The boys and I did not realize that we were wandering around the border area — it was just our common forests and meadows, cultivated wheat fields, and bends of rivers that had no beginning and no end.

Now, all these places of our childhood are mutilated by Russian aggression.

In the forest near Dvorichna, I received my first lesson in democracy.

One day, I was reading a book in front of a tent and heard screams from the pier. A crowd of 50 teenagers ran towards me, making noise and arguing. It turned out that the trainer told them: "Vote where you want to swim today — on a distant beach behind the forest or right on the pier in the camp." And the votes were divided precisely in half, so they ran to me as the only one who did not vote.

We were previously forbidden to swim at the pier, and my friend was also in favor of this option. That's why I chose it as well.

It may sound quaint, but I always vote in elections in Israel, particularly because of what I felt as a child in the forest on the Ukrainian Oskil River: my vote is important, my vote can be decisive.

Now, I am sure, both the pier and all the buildings of the camp of my childhood are smashed to pieces by cannonade.

In the same forest, I encountered a pure case of antisemitic hatred. In general, no one in the sports camp cared about my nationality; conflicts occurred more often along the lines of "basketball players against football players."

But one day a teenager came up to my tent and calmly said straight into my eyes: "I hate you because you are a zhyd [Ed note: a derogatory term for Jews]."

I remember that I became interested, asking him, "Why do you hate me if you don't even know me?" He replied, "Because my grandfather says so."

Probably, my interest as a researcher in the problems of antisemitism, ethnic stereotypes, and propaganda of hatred through generations stems from that conversation in a clearing near Dvorichna.

A memory: I go out after swimming in the Oskil River, and basketball trainer Serhii Ivanovych Korovai, a close Ukrainian friend of my father, gives me the command: "Two laps around the field!" I run barefoot on heated soil, alone in an endless mowed meadow. A freight train rushes past the Dvorichna-Kupyansk line.

And the bitter smell of sun-scorched wild herbs. When I catch similar smells of plants burnt out in the sun in Israel, that lonely run through the warm Ukrainian land immediately rises.

Fracture and scar

Behind our forest were the Chalk Mountains, a unique natural object. Going there was a trainer's reward for success in sports. One by one, they crossed the river on a flimsy suspension bridge.

When I hear a Hebrew song in Israel set to the words of Rabbi Nachman, "The entire world is a very narrow bridge, and the main thing is to have no fear at all," I again see myself as that Jewish teenager walking along the staggeringly narrow bridge across the Oskil, holding tightly to the thin handrails.

Through today's front line, which is shelled from all sides.

We found prints of prehistoric animals on the Chalk Mountains, which are made of pure chalk with traces of ancient mollusks. Now, this place is on the Ukrainian side of the front, seven kilometers from the border with Russia.

The Russian army destroys not only the cities and villages of Ukraine, created by humans 100-200-300 years ago but also destroys the Cretaceous deposits created by nature 70 million years ago.

That is why I perceive this war as a geological and tectonic fracture.

As a fiery, multi-kilometer-long scar, with which Russian aggression crippled and defiled even my Jewish memory of my childhood in Ukraine.

Kupyansk

The road home from Dvorichna to Kharkiv passed through Kupyansk. For a Kharkiv child, the word "Kupyansk" had an extraordinarily positive and tasty meaning because of the Kupyansk Milk Canning Plant.

Kupyansk condensed milk was the cherry on the top of children's happiness.

July 2024: "Fierce battles in the Kupyansk direction. Russian invaders are constantly shelling Kupyansk."

In Israel, I bought an export version of Kupyansk condensed milk with inscriptions in Hebrew — as a greeting from a distant childhood, which has been crushed by the tracks of Russian tanks for three years now.

I am keeping this tin can, to open it in honor of the complete liberation of the Kharkiv region and the victory of Ukraine.

Text and photo: Shimon Briman (Israel).