Searching for quiet waters: the life and writings of Bruno Schulz

Bruno Schulz is a writer and artist of Jewish origin, born in Drohobych. While his most famous works were written in Polish, he left his cultural mark in the memory of multiple peoples represented in Ukrainian Galicia in one way or another. He is now called a Polish or Ukrainian Kafka, but this kind of simplification does not give us a full idea of the true spirit of Schulz's oeuvre. While it is impossible to imagine Eastern European literature without his writings today, there was a period when only a handful of people remembered Bruno Schulz.

Once, more than ten years ago, I sat in the cool of a café looking at the portrait of a man in a disproportionate top hat on the wall. Outside the window, in the sweltering heat, lay a town I had imagined and read about in the books of the gentleman in the top hat. That imaginary town was starkly different from the real one.

The dark second-floor apartment of the house in Market Square was shot through each day by the naked heat of summer: the silence of the shimmering streaks of air, the squares of brightness dreaming their intense dreams on the floor; the sound of a barrel organ rising from the deepest golden vein of day; two or three bars of a chorus, played on a distant piano over and over again, melting in the sun on the white pavement, lost in the fire of high noon.

(Schulz, Bruno. The Street of Crocodiles. Transl. Celina Wieniewska, 1995)

This was Drohobych, one of the Galician towns with a special multicultural Ukrainian-Jewish-Polish flavor. This was the Drohobych of the writer and artist Bruno Schulz, who was born here on 12 July 1892. Jerzy Ficowski, a Polish poet and literary critic and one of the greatest researchers and promoters of Schulz's work, wrote:

"He was born at night, and having learned later from his mother that the July darkness greeted the first moments of his independent existence, he included the July Night as an important element in the topography of his individual mythology..."

Inspired by the memories of his visit to the Urania cinema, owned by his brother, Schulz wrote in the eponymous story about the magic lantern of childhood that cast light on his future path:

"Emerging from the blackness of the cinema walls, torn by the flashes of flickering reflections and shadows, I would drift to the subdued, bright lobby as a quiet house amid the boundless turbulent night."

As a naive reader, I tried to peer through the cracks of quotes from his works to see the whole world of his past. But the most I achieved then was stumbling upon a stumbling block, a memorial slab on the pavement where Schulz died. "Kissing stones" is a thankless task. It is much more rewarding to examine the urban palimpsest, discern the cultural layers, stop with a book in hand near the place where the author spent his childhood, stroll along Stryiska Street ("the Street of Crocodiles" in his writings), and come to his other house where his sister lived. Located at 12 Yuriya Drohobycha Street (then 10 Florianska Street), it has a modest plaque on the façade that reads, "Bruno Schulz (1892–1942), an outstanding Jewish painter and writer and a master of Polish literature, lived and worked in this house in 1910–41."

The street's name honors Yuriy Drohobych, another famous native of this town. A Ukrainian poet, philosopher, and astronomer active during the Renaissance era, Drohobych was the rector of the University of Bologna. Fascinated by celestial mechanics, he was remembered for his Latin-language prognostications, while Schulz was the earthly genius of this town. For a moment, it seemed to me that, united by the place where they were born and which they made famous, the two men accidentally met on the same street on different time planes.

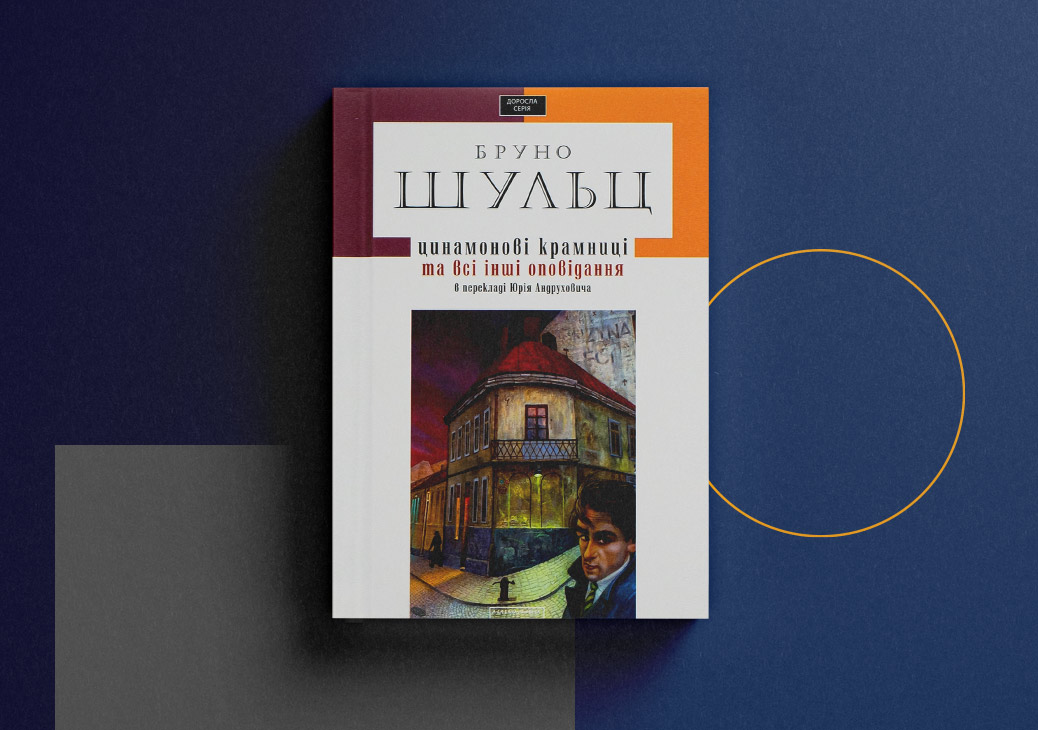

Returning to Florianska Street in Schulz's writings, somewhere in this house was a room he wrote about in The Cinnamon Shops:

The window of the room, filled to the brim with the sky, swelled endlessly with those undulations and shimmered with curtains that, blazing and smoking in the fire, flowed with golden shadows and trembling air...

In his works, the author returned to the lost paradise of his childhood and to the world of his father Jakub, whom he tried to "resurrect" in Sanatorium pod klepsydrą (The Sanatorium under the Sign of the Hourglass). (Klepsydra was also used in Poland then to refer to brief obituaries in the press.) He returned to his mother Henrietta and the magic and charm of the town he loved and knew better than anything else. Schulz called this work an autobiographical novel, a "spiritual genealogy."

Bruno Schulz studied at the Drohobych State Gymnasium, the Lviv Polytechnic Institute, and the Vienna Academy of Arts. He was born as a visual artist even earlier than as a writer. Ficowski quotes Schulz's letter to the Polish artist Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz:

"The beginnings of my drawing are lost in a mythological fog. I did not yet know how to speak when I covered all the papers and newspaper margins with scribbles that attracted the attention of those around me. […] When I was six or seven, my drawings featured the recurring image of a cab with a raised top and burning lanterns, leaving the night forest."

This image evolved in many of his mature works, becoming a kind of visual embryo.

In the early 1920s, Schulz embarked on the "Book of Idolatry," a series of engravings executed in the rare cliché verre (glass print) technique, full of sensuality, eroticism, male masochistic tension, and the mystery of female sadism.

These controversial works, which raised eyebrows in Lviv and Warsaw (immorality, how could he), bore early hallmarks of Schulz's artistic method — his truly idolatrous worship of matter in its alluring feminine essence.

Bruno Schulz's friend Izydor Friedman recalled:

"He was an obvious fetishist. (…) His fetishism lay in the fact that he was fascinated with beautiful long legs, necessarily in black silk stockings. Kissing such legs was for him — as he told me more than once — the greatest of pleasures."

From 1924 to 1941, Schulz worked as an art teacher at the Drohobych Boys' Gymnasium. Visual art preoccupied and exhausted him. He had obvious achievements, such as illustrations for the first edition of Ferdydurke (1938) by Witold Gombrowicz and graphics for his own Sanatorium. A collection of his works, about 300 in total, is kept in the Adam Mickiewicz Museum of Literature in Warsaw.

A fundamental shift occurred by the mid-1920s as Schulz began to express his images in writing. At the fashionable Polish resort of Zakopane, he met Debora Vogel, a fellow countrywoman and writer with whom he established an intellectual correspondence and shared motifs. In 1934, Vogel published a collection of poems, Mannequins, whose substance and diversity (in contrast to Schulz's all-encompassing fascination with a single mystical substance, its composition, and "its stubbornness and mushy clumsiness"), focused, as Vogel put it, on "the cheapness flooding the world." This acquaintance introduced Schulz to literary circles and became decisive for his prose debut. He became a sensation overnight thanks to the support of the then-famous Polish writer Zofia Nałkowska.

Magdalena Gross, Schulz's friend in Warsaw, recalled:

"Nałkowska told me to reread the first few pages, then interrupted me and said goodbye, asking me to leave the manuscript for her. She wanted to reread it herself. It was a comet meeting the sun… The comet flared up (…) Finally, at around 7 pm, came the long-awaited phone call. 'This is the most sensational revelation in our literature!' Nałkowska shouted. 'Tomorrow, I'm running to Rój to have them publish that book as soon as possible!'"

The year 1934 made Bruno Schulz famous. Inspired by success, he naturally continued to write stories that would later comprise the phantasmagoric Sanatorium dedicated to his beloved Józefina Szelińska.

Her figure deserves closer attention as she played a crucial role in Schulz's life and in the history of literature. Józefina ("Juna") Szelińska was a Polish translator, teacher, and librarian originally from Berezhany. She graduated from the Jan Kazimierz University in Lviv and taught in Drohobych from 1930 to 1934. In 1933, she met Schulz and was his fiancée until 1937. Agata Tuszyńska's book Bruno Schulz's Fiancée offers plenty of details about the life of this extraordinary couple: the "joint" translation of Kafka (actually done by Szelińska), problems with religion and marriage, her two suicide attempts, and above all, her painstaking efforts to bring her Schulz back from oblivion.

In 1936, Schulz received a six-month paid vacation in Warsaw. There, longing for Drohobych, he wrote to "The Republic of Dreams":

"Here on the Warsaw pavement in these days of tumult, heat and dazzle, I retreat in my mind to the remote city of my dreams, I let my vision rise to command that low, sprawling, polymorphic countryside, that greatcoat of God flung down at the sills of heaven like a mottled sheet. For that country submits utterly to heaven, holds heaven over itself in vaulted colors, variform, intricate with cloisters, triforia, stained-glass roses, windows opening onto eternity. (…) A good way to the south, where the mapped land shifts — fallow from the sun, bronzed and singed by the glow of summer like a ripe pear there it stretches like a cat in the sun, that chosen land, that peculiar province, the town unique in all the world."

(Bruno Schulz, Letters and Drawings of Bruno Schulz. Ed. Jerzy Ficowski, trans. Walter Arndt. New York, 1990)

As we know from Tuszyńska's book, Józefina yearned for something else:

"I didn't want to sacrifice myself for no reason anymore. I didn't want to get bogged down in the miserable and predictable everyday life of Drohobych. Its gloomy apparition always frightened me. (…) I decided that I would escape from Drohobych. With or without Bruno."

In short, behind the modest dedication "Not to my dear Juna, but to Józefina Szelińska" (dry, as Józefina described it) lies, as is often the case, a drama worthy of another book.

Around the same time, Schulz tried to arrange his exhibition in Paris, but the vacation time and limited contacts did not yield the desired result. However, he visited many museums and galleries and was fascinated by the rhythm of Parisian life. Ficowski cites Schulz's Parisian friend Georges Rosenberg in his book Regions of the Great Heresy:

"We spent one evening in a very fashionable, well-known Paris cabaret, the Casanova, on Montmartre. Schulz was much taken with the beauty, elegance, and dress of women with their 'stunning' décolletés, and he did not always realize the 'business' approach of some of the ladies. He asked me timidly whether he might caress the arm of the woman at the next table, who obviously had nothing against it. He was moved by the touch. I realized that he was a prisoner of his own fantasy and not a happy man. But he so dominated us all with the richness of his spirit, thought, and his poetry…"

In 1939, Schulz wrote to an acquaintance about his wish to retreat to some quiet backwater and finally, like Proust, set about formulating his own world.

The Messiah was supposed to become this opus magnum. Schulz wanted to finish this novel during his vacation, but the war broke out, and the text was eventually lost. All we have are isolated references. For example, the literary critic and essayist Artur Sandauer recollects the opening sentence in the manuscript:

"' You know,' my mother told me in the morning. 'The Messiah has come. He is already in Sambir.'"

Drohobych was soon incorporated into the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic. Schulz did not see a place for himself in those new circumstances, refusing to cooperate with the Lviv-based monthly Nowymi Widnokręgami edited by the pro-Soviet Polish communist Wanda Wasilewska. However, for some reason, he submitted a previously unpublished story to the periodical and received the answer: "We do not need Prousts." Still, Schulz had to make a living, so he painted portraits of Soviet figures for newspapers, posters, etc. This pseudo-artistic work only intensified his depression. As the German-Soviet war broke out in June 1941 and Drohobych found itself under Nazi occupation, Schulz entered the most tragic period of his life.

Carrying a Star of David armband and deprived of ways to make a living and support his sister and nephew, Schulz pinned his last hopes on his graphics. His graphical works caught the attention of Felix Landau, a Gestapo officer. Originally a carpenter from Vienna, he was a representative for Jewish affairs in Drohobych. This "patron" used Schulz as a "court painter": in exchange for food and patronage, he painted murals filled with fairy-tale characters for Landau's children in the villa he occupied in Drohobych. Meanwhile, the circle of death narrowed: his last close person, Anna Płockier, died in a mass pogrom in Boryslav. Then came the eviction to the ghetto at 18 Stoliarska Street.

Schulz wrote to Warsaw, asking for help. A false ID was delivered to him, but he did not have time to use it. Ficowski wrote:

"He died, shot dead on the streets of his hometown around noon, on the day of the planned escape, 19 November 1942, on the so-called Black Thursday, during the Gestapo's 'wild action.'"

Schulz was killed by Karl Günther as retaliation after Landau previously shot Günther's protégé, also a Jew.

Schulz's friends recollect that he took notes of the crimes and collected materials for a work about the most terrible martyrology ever. He said he had some 100 pages of notes, but these were never found.

In 2001, the German film director Benjamin Geissler discovered Schulz's murals in the "Landau Villa" in Drohobych. Larger fragments are now stored in Yad Vashem (following a scandal because they were smuggled out of Ukraine), while smaller details were transferred to the Drohobych Museum.

Sadly, Bruno Schulz, who designed the tombstones for his parents on his own, was secretly buried at night in an unknown place. Death, whom Celan described as a "master from Germany," decided then to hide many in the air — everywhere and nowhere in particular. As Schulz wrote in "Treatise on Tailors' Dummies, or the Second Book of Genesis":

"My father never tired of glorifying this extraordinary element — matter. 'There is no dead matter,' he taught us, 'lifelessness is only a disguise behind which hide unknown forms of life. The range of these forms is infinite and their shades and nuances limitless. The Demiurge was in possession of important and interesting creative recipes. Thanks to them, he created a multiplicity of species which renew themselves by their own devices."

(Schulz, Bruno. The Street of Crocodiles. Transl. Celina Wieniewska, 1995)

We will try to remember this every time we take his book off the shelf or attend the biennial Bruno Schulz International Festival in Drohobych in July, which brings together fans of the republic of dreams.

Yulia Stakhivska

Ukrainian poet, illustrator, journalist.

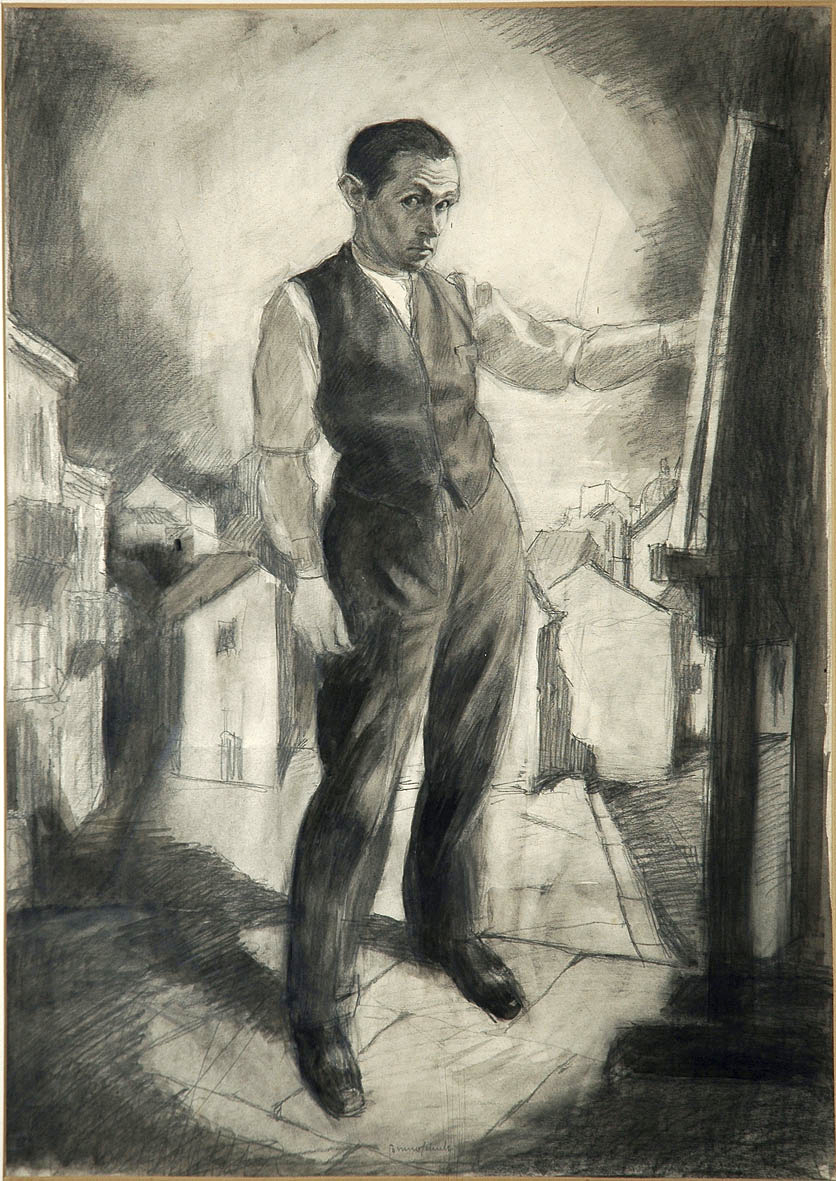

The illustrations are works by Bruno Schulz.

Originally appeared in Ukrainian @Chytomo

Translated from the Ukrainian by Vasyl Starko.

This material is part of a special project supported by Encounter: The Ukrainian-Jewish Literary Prize. The prize is sponsored by the Ukrainian Jewish Encounter (UJE), a Canadian charitable non-profit organization, with the support of the NGO "Publishers Forum." UJE was founded in 2008 to strengthen and deepen relations between Ukrainians and Jews.