The shared history of Jews and Ukrainians in two empires

We speak with the historian Anatoly Podolsky, director of the Ukrainian Center for Holocaust Studies, about the Beilis Affair in Kyiv, the [Russian] occupation of Lviv in 1914-15, and other topics.

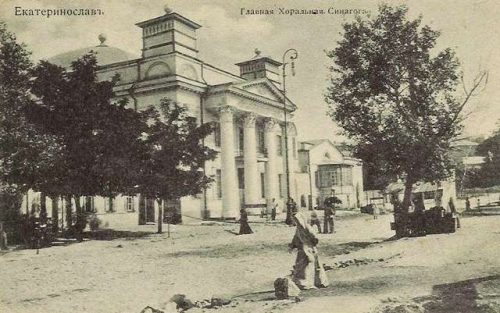

Andriy Kobalia: Before we begin, it bears mentioning that a so-called “Pale of Settlement” already existed in the Russian Empire, which encompassed some of the territories of Ukraine and Belarus. Jews could not live in other territories of the empire or this was quite hard to do. Where the Austro-Hungarian Empire is concerned, a policy of religious toleration was proclaimed as early as the eighteenth century. Scholarly opinions differ as to whether it was upheld. What is important is that such a policy of toleration existed officially. It is also worth mentioning the percentage of the Jewish population in the Ukrainian territories of the Russian and Austro-Hungarian empires. According to various censuses, Jews comprised half the population of Lviv, Odesa, and Katerynoslav, and one-tenth of the population of Kyiv.

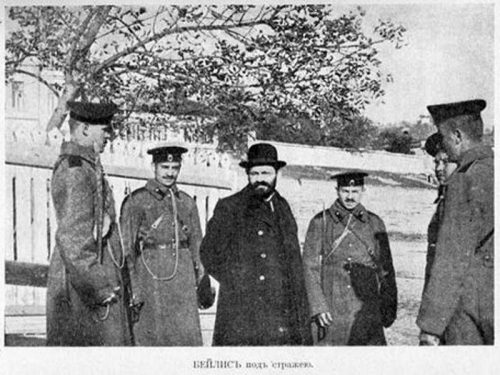

I would like to begin this conversation by broaching the subject of political organizations and the intelligentsia in the early years of the twentieth century. At the beginning of the twentieth century both the Ukrainians and Jews were stateless peoples, and it was during this period that political parties emerged. Did Jewish and Ukrainian parties and intellectuals cooperate with one another? I think it’s important to mention the Beilis Affair, which, in many respects, is reminiscent of the Dreyfus Affair that unfolded in France a few years earlier. I remind listeners that the Beilis trial took place in 1913 and involved the unjustified and—I would say—surrealistic—accusation that Mendel Beilis committed ritual murder. How did the Ukrainian intelligentsia react, and what is this case about within the general context of the Russian Empire?

I would like to begin this conversation by broaching the subject of political organizations and the intelligentsia in the early years of the twentieth century. At the beginning of the twentieth century both the Ukrainians and Jews were stateless peoples, and it was during this period that political parties emerged. Did Jewish and Ukrainian parties and intellectuals cooperate with one another? I think it’s important to mention the Beilis Affair, which, in many respects, is reminiscent of the Dreyfus Affair that unfolded in France a few years earlier. I remind listeners that the Beilis trial took place in 1913 and involved the unjustified and—I would say—surrealistic—accusation that Mendel Beilis committed ritual murder. How did the Ukrainian intelligentsia react, and what is this case about within the general context of the Russian Empire?

Anatoly Podolsky: As a historian by profession, you have very ably described the contexts. Indeed, the Ukrainian impact on Jewish culture and the Jewish impact on Ukrainian culture were very palpable. As for the question of cooperation among the intelligentsia, there is no question that it existed. Historians who study Judaica often compare these two cases that you mentioned: the Dreyfus Affair, involving a French officer, and the case of Mendel Beilis, an Orthodox Hassid from Kyiv, who was accused of ritual murder, which you mentioned earlier. He was acquitted in 1913.

As for contexts, it must be kept in mind that Ukrainian Jewry was a sub-group of the Jewish people, which was formed over a certain period of time, as was dual identity, wherein people remained in the bosom of the Jewish culture but were also integrated in Ukrainian culture. This process was quite a protracted one, and it became more developed in the twentieth century.

Two cardinal differences existed in this period. The Jews of Lviv, in the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and the Jews of Kyiv, in the Russian Empire, were integrated differently into these empires. The Jews of Lviv were part of that cultural space. They were Polish- and German-speaking. Jews in the Russian Empire, like Mendel Beilis, were absolutely not integrated. They were cut off from the context of life in the empire. They inhabited a ghetto of Yiddish-speaking culture. The attitudes of state institutions towards Jews in these two empires differed. In the Russian Empire, Catherine II declared that they were people of another faith; they always had to be reminded that they were guilty. This is what locked them inside that ghetto. The Jews of the Austro-Hungarian Empire were part of an enlightened cultural space.

There was a very large range of Jewish political parties within the communities of both empires. Above all, they were Zionist parties, left-wing parties. There was Nathan Birnbaum in Lviv and a whole array of political figures who dreamed of restoring the Jewish state in the historic lands of ancient Israel. [Birnbaum was born in Vienna and was a chief organizer of the Czernowitz Yiddish Language Conference. He left the Zionist movement at its very beginning, before 1900, and was a proponent of national cultural autonomy for Jews in Eastern Europe.—Ed.]

Andriy Kobalia: Did these political organizations cooperate with Ukrainian parties?

Anatoly Podolsky: Political figures like Simon Dubnow and Ahad Ha-Am were participants in the discourse within the communities. There were assimilated Jews, half-assimilated, Jews, Orthodox Jews. In 1897 the Bund socialist party was founded in Lithuania, Belarus, and the lands of Ukraine. The gist of the discourse was that Simon Dubnow championed cultural autonomy. Ahad Ha-Am proposed Zionism, which was also divorced from the territory. There were Zionist parties and socialist parties. It was precisely the Beilis Affair that exposed this cooperation between Ukrainians and Jews. As for political cooperation, everything was very complicated. Both the Jews and the Ukrainians felt like minorities. In Austro-Hungary there was in my opinion more cooperation. Concerning the Russian Empire, it is no wonder that people say that the political activities of Ukrainian Jews in Odesa led to the development of Zionism and the creation of Israel.

Volodymyr Zhabotynsky [Vladimir Ze’ev Jabotinsky], a translator from the English, was a very right-wing Zionist who in 1903 advocated the creation of Jewish self-defense detachments in the wake of the Kishinev pogrom. Zhabotynsky once wrote: “When I die, a friend of Petliura’s is buried here.” To him, Petliura was very acceptable and understandable. He said that Petliura, Hrushevsky, and Vynnychenko were fighting for Ukrainian sovereignty. And that is why we are similar.

Zhabotynsky’s approaches strike hard at Soviet, Ukrainophobic, and antisemitic stereotypes that were shaped by propaganda. I remember from my childhood that in Jewish families Petliura’s name was a symbol of the devil. But when we read documents, it turns out that he had the same kinds of plans [as the Jews] and that there was collaboration and that he was very upset by those pogroms. And that he spoke out against them. But as the head of the Directory, he carries responsibility. This is simply an exceedingly complex subject. But there was collaboration.

(Copyright: oldcity.dp.ua)

Andriy Kobalia: I think it’s worth concretizing things in connection with the role of the Ukrainian intelligentsia in the Beilis Affair. Were any statements issued? What was the reaction?

Anatoly Podolsky: It was an important trend when Jews were offered civic rights and participation in political affairs. But integration was too powerful. This existed in Italy, France, and generally throughout Western Europe. Jews became lawyers, physicians, and political figures. And Dreyfus in France was integrated into society. But all of a sudden he hears that he is being accused on the basis of his ethnic origins. The Beilis Affair is totally different because it was the result of policies formulated in St. Petersburg. During the reign of Nicholas II antisemitism was a state policy. The persecution of Jews was part of this policy, and various Black Hundreds organizations were financed through the state budget.

But there is always a possibility to remain a human being in inhumane circumstances. The Beilis Affair demonstrated this. When the Ukrainian Orthodox priest Aleksandr Glagolev testifies and states that the Jews did not use blood for ritual purposes, he is defending that Jew.

Unlike the Jew Dreyfus, who was absolutely part of French cultural society, the Jew Beilis didn’t even know a single word of Russian. [Scholars believe his knowledge of Russian was limited.—Ed.] He was a Hassid with four children. From morning to night his life revolved around one main idea: To thank God, to wash his wife’s feet, and to give thanks for his children and wife. Those family values that were always important to Jews. Living in Kyiv, Beilis was not part of that context. He did not understand the accusation against him.

And here we see, for example, Volodymyr Korolenko, who defends him. We see Arnold Margolin. We see Ukrainian, Russian, and Jewish intellectuals. As you have said, as [Orest] Subtelny wrote, Ukrainians and Jews were stateless peoples. Glagolev defended Beilis, and in 1941 his son Aleksei and his family rescued Jews. And this is very important.

Andriy Kobalia: The next important point in the experience of shared historical events is the occupation of Lviv by the Imperial Russian Army, which lasted from September 1914 to April 1915. What was life like for Jews and Ukrainians during the occupation of Lviv?

Anatoly Podolsky: Once again, this the next episode in the history of Ukrainian Jews. Writers noted subsequently that it seemed as though after such horror, there could be no greater horror. Ten million lives were lost during this war. But it changed nothing. Twenty-five years later the Holocaust began. Heinrich Böll co-wrote a book with Lev Kopelev, Why Did We Shoot at One Another? The lack of an analysis of memory leads to repetition.

Returning to the topic of the First World War, we can cite Felix Kandel and his essays on periods and events. He [is] a very interesting writer, whose writings confirmed Subtelny’s thesis that Jews and Ukrainians were stateless peoples. Kandel writes that Jews from Austro-Hungary and Russia met on the battlefield. And he cites examples from memoirs of the First World War, indicating that battles took place in 1915 in the lands of Eastern Galicia. And when a soldier there took another’s life, he read a prayer. Kandel described these events.

But it is important to know that Jews regarded Austro-Hungary as their fatherland, and they defended it, just like the Ukrainians. You mentioned that edict of Franz Josef’s, from 1781. [The Patent of Toleration granting religious freedom to Lutherans, Calvinists, and the Serbian Orthodox was issued on 13 October 1781 by the Habsburg emperor Joseph II. The Edict of Tolerance issued 2 January 1782 lifted many restrictions on Jews but maintained others.—Ed.] In 1791 Catherine II’s ukase about the Pale of Settlement was issued. If we compare [these two documents], we must state that over there was an open path to social life, but here people were in a ghetto. Apropos Lviv, there are memoirs describing that horror. One can cite Shloyme An-ski. He was an ethnographer, researcher, and writer, who traveled throughout Ukraine collecting folklore. He was one of those individuals who helped Jews in the aftermath of pogroms. The Russian army’s pogroms in Lviv against Jews were horrible. And Ukrainians suffered as well. This subject is extremely complex and poorly researched. There are sources in the Yiddish language. These are memoirs of Jews who survived the pogroms, not just in Lviv, but also in small towns.

The pogroms carried out by the Russian army in Eastern Galicia led to the creation of a fund that turned one hundred years old last year: the civic organization “Joint,” the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee. It was founded in order to help Jews after the pogroms in Eastern Galicia. And it exists to this very day.

Andriy Kobalia: We have talked about the occupation of Lviv, diaries. In my opinion, we should also touch on who the Jews were in these two empires. And what was the mortality rate among Jews during the First World War?

Anatoly Podolsky: First of all, who they were. We can cite examples based on personalities. Bruno Schulz was a well-known writer and artist. He was killed by a German officer in the ghetto in 1942. How did he view himself? He was proud of being a citizen of Austro-Hungary. Above all, he loved the Ukrainian city of Drohobych. Polish was his native language. His parents were Orthodox Jews. People who write about him ask: Who was Bruno Schulz? He was born in Drohobych, he was a subject of Austro-Hungary, his native language was Polish, he was born a Jew. He was prepared to renounce Judaism because he believed that the main thing in life was love. For the sake of his beloved wife he was ready to abandon Judaism and convert to Catholicism. That is, the trait of Jews in Austro-Hungary was the trait of cosmopolitans. Because the imperial government had a tolerant attitude to culture and religion, whereas absolute intolerance and phobia existed in the Russian Empire.

Returning to Schulz, he wrote that he spent time in Vienna, Lviv, and Drohobych. “With all due respect, Vienna and Lviv are worth nothing because the main thing is Drohobych. My native city.” Love of Ukrainian territory. In the Russian Empire, Jews were afraid and they locked themselves inside their culture. They hid in ghettos, where they hid from the majority so as not to opt for integration. As for the mortality rate, that is difficult to say. But there is research on the period from 1914 to 1920.

Pogroms were carried out by both Whites and Reds, as well as Ukrainian nationalists. Unfortunately, this is also a tragedy of a stateless people. Ukrainian nationalists and the Whites accused the Jews of collaborating with the Bolsheviks; the Bolsheviks—of collaborating with Ukrainian nationalists. It was awful. The number of victims reached between 100,000 and 200,000. There were terrible pogroms in Podillia. In the cemeteries of these cities you will see a whole pantheon [of gravestones] where the death date is 1919 or 1918. These are victims of pogroms. During the First World War and the liberation struggles the Jews often supported the Ukrainian side. In November 1918 Jews expressed trust in the Western Ukrainian National Republic. And in the government of the UNR [Ukrainian National Republic] there was a Ministry of Jewish Affairs. [Moisei] Zilberfarb was the minister of Jewish Affairs.

Andriy Kobalia: To conclude our conversation, we can mention events that took place later. During this period Ukrainians were arrested for so-called “bourgeois nationalism,” and Jews—for Zionism.

Anatoly Podolsky: Ukrainian-Jewish history has been neither positive nor negative. It has been very complex and ambiguous. Cooperation in those days is revealed clearly in the memoirs of Jews and Ukrainians who survived Soviet labor camps. We have the memoirs of Mikhail Kheifets, Vasyl Stus. In the 1950s and 1960s UPA soldiers and dissidents and Jews, who ended up the camps for studying Hebrew, were there also. The cooperation between Jews and Ukrainians in the camps is a great foundation for future dissertation research.

This program was made possible by the support of the Canadian philanthropic fund Ukrainian Jewish Encounter.

Originally appeared in Ukrainian (Hromadske Radio podcast) here.