Sheptytsky is much more profound and complex

The metropolitan on unity against the backdrop of the reigning ideas of Nazism and racial separation

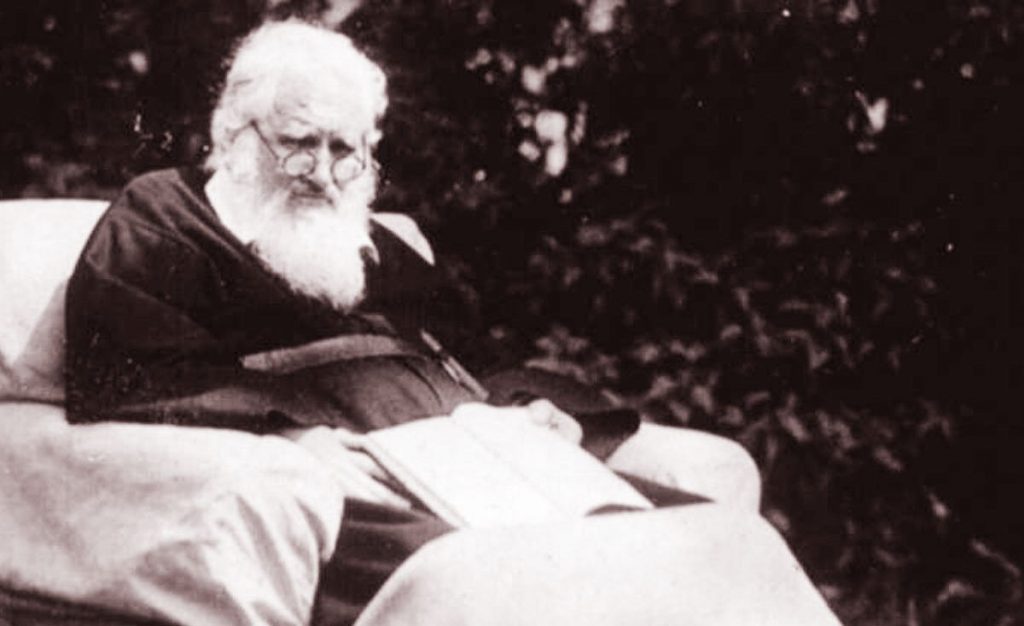

Metropolitan Andrei Sheptytsky did not leave behind any collections of philosophical or theological works or major fundamental treatises. He expressed his most interesting and important thoughts in his epistles and appeals to the clergy and the faithful. In these works, he attempted in an accessible manner to inform his parishioners about important moral and ethical problems. It must be said immediately that at times Sheptytsky’s thoughts, by their form and content, did not correspond to the main currents of that period, so much so that they risked not being heard. In recent decades, thanks to semi-popular publications as well as films, we have become accustomed to perceiving his persona somewhat schematically, adhering to the narrative of “Sheptytsky, the Moses of the Ukrainian people” or “Metropolitan Sheptytsky, the father of the Ukrainian nation and statehood.” However, this superficial point of view does not allow us to see a different Sheptytsky, one who is much more profound and complex.

In several of his works, the metropolitan discusses the question of unity. For the most part, we are accustomed to thinking that he means the unity of the Ukrainian people and the Ukrainian Church. In his epistles, the metropolitan does, indeed, frequently raise the question of the unity of the Church and the unification of Ukrainians, who were separated by the borders of several states. However, even when Sheptytsky reflects on the unity of Christ’s Church, he is contemplating not only the unification of the Ukrainian Greek Catholics and Ukrainian Orthodox. The metropolitan was addressing the mutual understanding and unification of all Christians because, in his view, this was the ideal. This was the covenant of Jesus Christ. For the metropolitan, the unity of the Church begins to acquire a deeper and all-embracing importance, especially during the Second World War. For example, the text of the decree “Work on the Unification of Churches” (1943) contains the following interesting words: “Unity among people corresponds to God’s will, to God’s intentions concerning humankind. God’s ten commandments are only an application, to the individual needs and aspects of human life, of the two main commandments: love of God and love of one’s neighbor.”

For Sheptytsky, a unity for the sake of Christ also signifies a mutual understanding and the peaceful cohabitation of all members of the human community. I will say immediately that this ideal state can be reached, in his opinion, “only by sincere work on Christian love of God and one’s neighbor.” In his epistle “On Mercy” (1942), the metropolitan explains what love of one’s neighbor should be like and who our neighbors are. About love of God and love of one’s neighbor, he writes: “We love God in our neighbors, we love them for the sake of God…” He also appeals to each person to be prepared for at least a drop of sacrifice: “And the highest degree of love is to give up one’s life for a loved one…in the desires of the soul, in each love of one’s neighbor there must be at least something of that sacrifice, there must be readiness for that sacrifice.”

The metropolitan clearly identifies who must be considered one’s neighbor: “...all of one’s neighbors in general, that is, outsiders, infidels, atheists, and enemies.” Sheptytsky believes that all of us, the people of this planet, are one another’s neighbors: “For each neighbor is a brother, a member of that human family that grew out of the family of the first man.”

The above-cited words about the unity of humankind were written in June 1942, at the height of the Second World War. Nazism was implementing at the time the ideas of the racial separation of humankind into ruling and inferior nations as well as those that are subject to total destruction. The metropolitan was talking to his faithful about a unity among all people on the planet, about their common origins, and about brotherhood among them, at a time when the utter destruction of the Jewish people was taking place on the territory of his archeparchy. In his epistle “On Mercy,” the metropolitan seeks to convince his faithful that people of a different faith, with a different language, are their neighbors and therefore must be treated with love. Moreover, the words about self-sacrifice for love of one’s neighbor at that time, in 1942, were also addressed to those who could help Jews but were afraid or hesitant. The metropolitan’s words were no less concerned with those Ukrainians who were under the sway of racial theories and ideas of national exceptionalism.

Metropolitan Sheptytsky first formulated his idea of the unity and solidarity of humankind in 1934 in his epistle “Who Is to Blame?” This pastoral letter is extremely interesting, important, and—unfortunately—little known. In it, the metropolitan talks not only about the complicated problems of Ukrainian society, as though predicting even more complicated times that were awaiting his flock. He also formulates his thoughts about the solidary responsibility of mankind. I will cite from this work:

“For all of humankind is one family, one organism, a unit of the highest order, and just as the same blood circulates in all people, as everyone breathes the same air and consumes the same foods of the earth, so too spiritually are all people one body, for which merit and punishment are a common good or evil. The fate of the globe is common to us…On the basis of that physical solidarity, the sickness of one transmits to another; the labor of one becomes the good of all; every invention and…every work of the human spirit becomes the general good of humankind. But that which is evil, a crime, a shame, hatred is also common to all humankind.”

When the metropolitan wrote these words to Ukrainian Greek Catholics, the most popular among them were the ideas of nationalism, as they were among the majority of European nations. Another global ideology also divided humankind into enemy camps, but according to the class principle. The metropolitan sought to raise his voice against these totalitarian ideas that led to the outbreak of the bloodiest war.

Sheptytsky believed that humankind would only be able to develop harmoniously once it acknowledges and understands its unity and solidary responsibility. Do these words not seem topical today, in 2021? We are increasingly coming to realize that climate problems or a pandemic can only be overcome jointly and in solidarity. In the same way, problems of security and peaceful cohabitation can be resolved only when political leaders start looking at them from the standpoint of a solidary joint responsibility.

Liliana Hentosh

Liliana Hentosh is a Candidate of Historical Sciences and Senior Research Fellow at the Ivan Franko Lviv National University’s Institute of Historical Research. She is a leading scholar on the life and work of Andrei Sheptytsky, Metropolitan Archbishop of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church.

Originally appeared in Ukrainian @Zahid.net

This publication is part of a project supported by the Canadian charitable non-profit organization Ukrainian Jewish Encounter (UJE).

Translated from the Ukrainian by Marta D. Olynyk.

Edited by Peter Bejger.

Related video: Andrei Sheptytsky: A Count Who Became a Priest, Ukrainian Institute London

NOTE: UJE does not necessarily endorse opinions expressed in articles and other materials published on its website and social media pages. Such materials are posted to promote discussion related to Ukrainian-Jewish interactions and relations. The website and social media pages will be places of information that reflect varied viewpoints.