Six Cups

A wedding present, a family history, and Ukraine’s dark 20th century, 75 years after Babi Yar

The miniature porcelain cups sitting in the china cabinet of our dining room have long been my favorites. From childhood, I admired their delicate form and the images of Napoleon and his second wife, Marie-Louise, Duchess of Parma, framed by decorative patterns. The blue-and-yellow cups accented with golden hues were accompanied by three similarly decorated saucers. As a child I often gazed at them, imagining a more fanciful era.

After trips home from overseas travels, I dusted the cups, placing them back carefully in their traditional place against the cabinet wall. One day, on a phone call with my aunt during travels to a land Marie-Louise had ruled, I mentioned the cups and wondered where my late father had purchased them. He loved to collect antiques and had amassed over the years many pieces of silver, crystal, and china, all displayed in the cabinet.

“They were never your father’s,” my aunt said, much to my shock. And then she shared their story.

One evening in what must have been the spring of 1941, a knock came on the door of the apartment my grandfather and his family inhabited in German-occupied Krakow, Poland. Upon opening it, my aunt found a husky well-dressed Jewish man she had never seen before.

“I am looking for Oleksa Yaworsky,” the gentleman said. My lawyer grandfather often received clients at home so my aunt led the man to his cabinet.

Inside, the man pulled a wooden box from his underneath his coat and placed it on Grandfather’s desk. Opening it, he revealed six small cups, three bearing the image of Napoleon and three of his wife Marie-Louise.

“They are taking us tomorrow,” the man said. “If we survive, I will contact you and take them back. If not, I entrust you with their safekeeping.”

They were, he said, his wedding present.

The man never returned for the contents of his box.

***

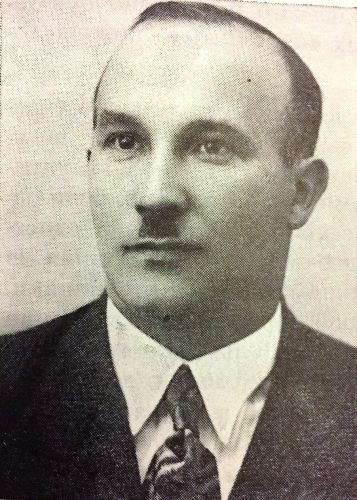

My grandfather was born in 1896 in the village of Kotuziv at a time when relations between Ukrainians and Jews were affable on the territory of what was then known as Eastern Galicia in the Austro-Hungarian Empire ruled by the Habsburgs in Vienna. Although Kotuziv “birthed few intellectuals,” as he put it, my grandfather attended the gymnasium in the nearby towns of Berezhany and Buchach, being the only of his five siblings to get an education.

Like many of his compatriots, my grandfather fought for an independent Ukrainian state during World War I. When dreams of freedom ended for the Ukrainian people, he studied law at the clandestine Ukrainian university in Lviv, established after the Poles abolished Ukrainian-language faculties from the Habsburg era. He married my grandmother, a medical student, in 1922. After the university failed to receive official recognition from the ruling authorities of the Second Polish Republic, he entered Krakow’s famed Jagiellonian University. He again studied law, keeping awake at night by sticking his feet in buckets of cold water. He graduated in 1929, and soon after opened a notary office in Pidhaitsi, a town a mere 12 miles northwest of where he was born. He was active in Eastern Galicia’s political life, traveling through villages educating its Ukrainian inhabitants about politics and their rights.

He ran for a seat in Poland’s parliament from the Ukrainian National Democratic Alliance, the largest Ukrainian political party in the Republic, and won twice, in 1928 and 1930. UNDO was democratic, supported agrarian reform, the expansion of the Ukrainian cooperative movement, and worked closely with women’s organizations.

UNDO supported Jewish civil rights, and protested acts of antisemitism and attempts to limit Jewish cultural practices. UNDO concurrently favored Ukrainian economic development, the expansion of cooperatives, and the boycott of non-Ukrainian businesses, which created inherent economic tensions with Jewish- and Polish-owned firms. The party denounced the acts of terrorism practiced by the radical Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists.

In 1935, tired of surrendering part of his salary to the party as required, my grandfather opened a law office in Pidhaitsi. It did not come without a struggle. Short on funds, his fellow Ukrainians found reasons not to lend him money. One day walking through downtown, dejected, he ran into a Jewish friend, who asked why the sad face. Grandfather explained the situation. Immediately, the man offered to lend him the money. My grandfather insisted he sign a promissory note. The man refused.

“You will have a very successful business and pay me back soon.”

My grandfather did, and life in Pidhaitsi took on a regular tempo, as regular as it could be in that politically uncertain time.

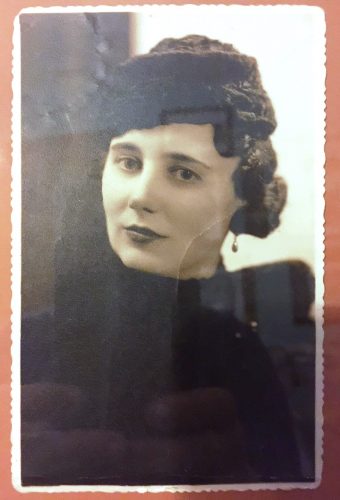

The family had rented quarters in a building owned by the rabbi’s brother. My aunt remembers the rabbi coming over and bouncing her on his lap. She’d pull on his beard; he’d give her matzah, a food she loves to this day.

My grandfather continued to be involved in Ukrainian community affairs, traveling throughout Eastern Galicia, propagating ethnic and political rights. Then hell pierced the skies of Europe and the rhythmic lives of millions came to an end.

On Sept. 1, 1939, my grandfather was arrested by the Polish authorities and taken to Bereza Kartuska, an internment camp for individuals the Polish state viewed as a threat. Just over two weeks later, the camp shut down, after staff learned the Soviet Union had invaded their homeland.

It took just as many weeks for my grandfather to return to Pidhaitsi. No sooner had he arrived than a Jewish friend, seeing him, warned, “Oleksa, what are you doing here? The communists are looking for you.”

A day later, my grandfather headed for Krakow, a city he had come to know well. The family settled in an apartment near Wawel Castle. Life in Krakow centered on school, Ukrainian community life, and work. My aunt remembers playing at the park across the street from their home, known as the Planty, and seeing and hearing a melody of recognizable people.

“And then one day, the Jewish children were all gone,” she said in another phone call many years after she shared the story of the wedding cups.

I knew that my grandfather had administered a Jewish business in Krakow. But what I didn’t realize was the first apartment where my family lived in the city was owned by a Jewish businessman, a Mr. Holzner. It is not clear to me how Grandfather came to administer Mr. Holzner’s wholesale watch business, which was located on Swietego Sebastiana 4, a stately street near Wawel Castle. In January and February of 1940, all of Krakow’s Jewish properties and enterprises, with the exception of small shops, were confiscated by the governing German authorities. Germans were given the important enterprises to run while Ukrainians and Poles the less significant, like the watch business.

My grandfather, however, arrived in Krakow in early October 1939 and moved into the Swietego Sebastiana 4 apartment before this order was issued. It may be that Mr. Holzner reached an agreement with my grandfather about running the business before he and his family had fled to Switzerland. Or perhaps not.

What is known is that three Jewish workers stayed on and unofficially ran the company. According to my aunt, my grandfather was able to secretly transfer funds to Mr. Holzner in Switzerland. In a 2008 email, my aunt wrote:

How and how much I don’t know, and eventually Holzner immigrated to Brazil, where he opened a bank. After the war Dido [Grandfather in Ukrainian] wrote to him in Brazil, but Holzner did not answer and Dido did not pursue it further. Holzner’s father fled to Lviv from Krakiv [Krakow] and when he found out that Dido administered his son’s firm (Germans called it “Treuhandel” and Ukrainians referred to it as “Treuhandelka”) he was very pleased. Eventually it was taken from Dido on the basis that “eigentlish es regieren drei Juden’—“in truth it is being administered by three Jews.”

The short period the family lived at Swietego Sebastiana 4 was filled with anxiety. My grandmother and mother were so sick from their Pidhaitsi journey upon their arrival in Krakow the doctor visited them daily. Shortly thereafter, the Germans appeared at the apartment to wrap up and categorize all its valuables. A German officer grabbed a silver sugar cup that sat on a table, prepared to add it to the list of Jewish possessions to be confiscated.

My grandmother yanked it back, saying it was her wedding present. The German, after some begging, relented and let her keep it. But several days later, the Jewish belongings were gone.

Not long after, the family moved to Zelena Street, known today as Jozefa Sarego, No. 4.

About Krakiv: find out where the Jewish Ghetto was located. [Grandfather] had Jewish friends there, especially one friend which he studied law in Krakiv with. He passed through the ghetto to the court house and he always took some food to him. As a lawyer he tried to get them some passes (they needed to have a pass to get out for the day) to prolong their stay in Krakiv so they would not be sent to the concentration camp in Auschwitz. Finally, the Gestapo called Dido for an interrogation and the man in charge told him that the Gestapo knows all the fonts of all the typewriters in Krakow and Dido better stop writing petitions if he wants to continue to practice law. So soon afterward Dido closed his law office and opened a notary in the town of Sambir to which he commuted and he lived a few days [a week].

I spent one afternoon in the mid-1980s interviewing my grandfather. Memories lingered on early years. He remembered “Blaustein,” a Jewish neighbor in Kotuziv, and his friend Leo Brinks, who joined the fight for Ukrainian independence and with whom he “lived like with a brother.”

He shared a single episode from Krakow.

“Innocent children were murdered. I had a Jewish friend whose wife and her sister were taken away. He was able to hide the [sister’s] child. They later found the child, and they in this way murdered children, by taking them by their feet and smashing their head against the wall. That is how they killed children.”

The murdered child was a newborn.

***

Two chapters in my family story underscore the difficulty of the Ukrainian experience during WWII. Both deserve their own essay, but it is important they are mentioned.

The first is that in the spring of 1944, my grandfather was drafted into a Ukrainian division of the Waffen SS, commonly referred to as the Galician Division. At first, he thought the letter he received was a joke because he had never heard of anyone being drafted into this mostly volunteer force. It was made clear to him, however, if he did not want to have “unpleasantness” he would join. His job was to help the families of the “Divizinyky,” as they were known.

The other chapter is that by marriage I am associated with Stepan Bandera, the leader of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists. My grandfather knew him personally, and did not have a high opinion of him. He did not sanction the organization’s tactics, even as he understood the fight for an independent Ukrainian state. The unfortunate truth is we bear the legacy of our associations, even if we object to them.

I don’t want to idealize my grandfather. He was not heroic, but he also was not passive or indifferent. And so I believe him when he told me, “I lived well with the Jews.”

That is perhaps why an unknown man entrusted his most important possession to my grandfather, Oleksa Yaworsky. The paradox is that my grandfather, who left Krakow for Vienna near the end of the war, packed up the family’s belongings in a large trunk, including the silver sugar cup my grandmother had wrested from the German. The trunk never reached Vienna. It was lost forever in the last days of war.

The wedding cups were packed in a suitcase and carried by hand to Canada, where my family found refuge. Late in life, my grandfather later divided the set of six cups between my aunt and my mother. The three I grew up with were placed in our china cabinet, their story untold, until a phone call revealed their complicated truth.

Next year [2017] the wedding cups will go to a Jewish museum in Ukraine, accompanied by their story. I cannot fathom the loss of millions of Jewish lives during the Holocaust, but I can honor one memory and hold to a promise made decades ago in a Krakow apartment, to ensure their safekeeping. The cups were never ours. For me, this is their lesson.

This story originally appeared in Tablet magazine.