The daughter of a “batiar”: Ukrainian woman recognized as Righteous Among the Nations in Israel

Why did her family save Jews during the Holocaust? What was the truth behind survival and the ordinariness of death during the occupation through the eyes of a child? I spoke about all this with Yaroslava Levytska [Jaroslawa Lewicka], the only Ukrainian recognized as a Righteous Among the Nations who has been living in Israel for nearly twenty-five years.

Yaroslava is the youngest person ever to be granted this title for her participation in saving Jews. When she was six and a half years old, the city of Zolochiv (Złoczów), in Lviv oblast, Ukraine, fell under Nazi occupation. From age seven to nine, she helped her grandfather and mother carry food to Jews in the ghetto. Her family saved four Jews and helped save a group of twenty-five Jews who were hiding in an underground bunker in another part of the city.

The website of Yad Vashem, the World Holocaust Remembrance Сenter, states that three generations of the Levytsky family helped saved Jews: grandfather Oleksandr, his daughter, Kateryna, and his granddaughter, Yaroslava. Immediately after the occupation of the city of Zolochiv by the Germans in July 1941, Oleksandr Levytsky came to the assistance of his Jewish friends, who were in trouble.

As the Nazis introduced anti-Jewish laws, the elder Levytsky began supplying his Jewish friends in the ghetto with food and medicine. “He would not have been able to do so without the help of his courageous granddaughter, Jaroslawa, who acted as his courier without awakening the suspicions of the Ukrainian guards,” Yad Vashem states on its website.

In 1952 Yaroslava graduated from High School No. 2 in her native city, and later from a medical college. She worked for ten years in the countryside and later as a disinfectologist at the Zolochiv raion [district] Center for Disease Control.

In 1989, on the initiative of one of those who was saved, the Israeli Abram Shapiro, Yaroslava, her grandfather, and her mother were awarded the title of Righteous Among the Nations. In 1995 the State of Israel granted them citizenship, a pension, and an apartment.

I spoke with Mrs. Levytska in a beautiful park near her building; guests are not permitted into the building because of COVID-19. I present below our conversation in the form of Mrs. Levytska’s own words, in order to give readers the opportunity to hear the direct voice of this Righteous woman and her recollections in the first-person.

The beginning of the tragedy

“At first, my grandfather was a carpenter; he built churches around Zolochiv. He was very devout. We were Greek Catholics. We knew that we were not Roman Catholics because we were not Poles. People did not even talk about Orthodoxy at the time. My grandfather received a disability pension during Polish rule.

Our family was extremely poor. My father was given a small plot for a garden. Our house stood right next to the road to Brody. My mother, who was born in 1903, came from a poor family from Zaliztsi; after the First World War, her house burned down.

In September 1939, a Polish officer hid in granny’s attic. He was being hunted by Red Army soldiers, but they did not find him. Mama boarded up the windows and covered us children with a down comforter.

We had a diesel-powered mill. Next to it was a watermill owned by a Jew named Ritter. [In 1939] the Reds seized the mills but immediately gave people jobs.

We lived altogether with the Jews on the same street; it was called Koloniia. You ask why we decided to help Jews.... We were all neighbors! All of us were the same people; it doesn’t matter [what nationality].

Mama dressed us identically. My sister and I had little coats, and then our neighbor, Basia [a Jewish girl], was growing, and we gave her a hat and the coat. We lived on the same street, and there was no difference. And when that misfortune happened, we helped with whatever we had. In our souls, in our hearts, we never even thought about their being of the Jewish nation; just people, neighbors.

When we saw Basia being taken away [to be shot], we screamed and cried so much. “Oh, they’ve taken away our Basia already!” We were so sorry. Mama could not look at this calmly. She covered the window with a bedspread so that we would not see anything.

My father went to school with them [Jews]. We loved these children; we grew up with them. I cannot even imagine how it is possible not to love children so much!”

The ordinariness of death through the eyes of a child

“Do I remember the pogrom of July 1941? Mama did not let us go there. People were celebrating the harvest. They were all carrying sickles wrapped in ears of grain and wearing Ukrainian attire. I couldn’t walk; I was ill at the time. Everyone went to the stadium; there people said that Ukraine is now independent. Whoever wants can enlist in the army…

We were told right away that there would be a crackdown on the Jews. But we took this to mean that it would happen to us. That they would be the first, and we would be next. That the same thing would happen to us. The Germans will destroy them then us.

But there were different kinds of Germans. One in our apartment told us after Stalingrad: ‘Stalingrad: Germany’s kaput.’

... Strassler had a candy factory inside the ghetto; mints and red sweets, they were manufactured in two shifts. We were given candies, and I brought them [out of the ghetto]. I brought packages underneath the barbed wire; I knew how to get in through the back. I brought them fruit.

...Truck after truck drove into the forest [the site of the mass shootings of Jews in Zolochiv in April 1943, near the village of Yelykhovychi—Sh. B.], and they were shot there. A truck with submachine gunners arrived from Lviv. Neighbors said that Jews were living close by. The earth moved for many days.

...The Ukrainian police took part. An incident took place before my very eyes. I was walking home with two neighbor girls. The road here is going uphill, and the truck has to shift gears and brake. A Jewish woman jumped out of the truck and is running toward us. A Ukrainian policeman was sitting [in the cabin]. And he jumped out and is running toward us. The poor woman had nowhere to run, she cannot run into the nearest building, it’s closed. She heads in another direction—there’s barbed wire. She can’t move in any direction. And he’s racing after her and shouting at us, asking why we are walking there, ‘that because of the lousy Jewess I could have shot a child!’

He shot her. We came up to her. Blood was pouring out of the left side of her head. I saw with my very eyes; she was wearing a light-brown, polka-dot jacket. Her hood was cherry-colored, brownish-black. She was a beautiful woman. And it was obvious that her pocket was full; something was sewn inside it. We came home, a female neighbor wrung her hands and says: ‘Oh, this is the wife of our friend, the doctor from Sasiv!’ And I say to my sister that we will go and see, maybe that money in her pocket is still there. We came, but the pocket was already empty. I don’t know who took it. A truck came, but there are always people around; it was a main road.

[Another time] I saw two sons being shot. They were lying next to each other, and their father alongside them. Maybe policemen had shot them.”Mama and Grandfather

“Abram Shapiro from Brody ended up in the camp [near Zolochiv]. He got out and came to our neighbors’ house. The neighbor woman says: ‘I am begging you. I have one child. If I am caught because of you, they will kill you, me, and the child.’ So, he crossed the road and went to our house.

Mama came and she tells us: ‘A boy, a red-haired one, came at four o’clock in the morning. If I am caught with him, know that if I don’t come back, they have shot both me and him.’

We knew that we could be shot. But we did it. There was no question.

And Mama brought him; she knew where to enter the ghetto unnoticed. She told him how to continue on. ‘And there you will say “from Levytska’s.”’ Later they used him [Abram]: They gave him handfuls of candy; they cut up the candy. And he came to my grandfather. My grandmother prepares potato pancakes during the day, and he ate them cold at night. And he would go and bring food to the ghetto. He was like a courier. My grandfather went from the village and bought tobacco, twisted it, and cut it, and brought it to the ghetto.

We traveled by train to our friends, took butter and other foods. We didn’t have money. But Jews gave clothing, and we traded their things for food and helped them. One time a German hit my mother and didn’t let her bring food into a Jewish house with a brownish-deep red Jewish star painted on it.

That bunker [where a group of Jews was hiding] was accessed through a hatch; you had to go through the sewer system. My grandfather went there.

There was a [Ukrainian] policemen, who before the war had been in love with Ruzka Shenker [née Roza Feiering—Sh. B.]. The Feierings were millionaires.

And he found out that her son, Yurko Shenker, was crying underground, that he doesn’t want to be there [in the bunker]. We fed their Yurko; he was brought to us for two or three days. They dressed him in a kerchief and a dress. And I am wearing a dress, and my sister, too, and the three of us were walking along. But all of a sudden, a female neighbor arrived from far away; she had brought milk. And my father pushed him with all his might under the bed. Yurko played with toy soldiers, and my father stepped on a toy soldier. Then Yurko recounted ‘how Petro had stepped on a toy soldier; he lay there worrying that he would crush his toy soldier.’

We were afraid of everyone. And then during the night that Ukrainian policeman and my grandfather took Yurko Shenker on horseback to Pidhirtsi, where they had their own brewery. And that’s how they saved them. I still have a photograph of Yurko.

When the Red Army came, the Jews left the bunker and went to America. Afterwards, there was no contact with them. Many policemen also left for America.

Abram had a brother in Haifa, and he went to Haifa. He was very jolly and brave. I saw him when he invited me to Israel to award me the title of Righteous. He drove me around the country in his car. He thanked our family very much.

He was angry with that Ruzka Shenker. She had a pass and could leave the ghetto, and she would go with that pass to our place. There were workers there who were employed by the Germans. Shenker was an engineer.

Abram and I communicated in the Ukrainian language. He understood and knew everything.”

An honorable “batiar”

Ukrainian Wikipedia states that the Lviv batiary were an urban subculture that existed in the 1920s and 1930s. The term batiar means a person who lives by his wits and engages in unexpected mischievous acts; a daredevil, a rake.

“My father was in Lviv for two years [before the war]; he worked there and did not go to confession. Later he went to Zolochiv for confession and told the priest this. That priest shouted at him, the sound carrying through the entire church; so he left. And my grandmother, his mother, came from church the next day and says: ‘The priest said from the pulpit that a young fellow up and left confession, and I just knew that that was you; no one else could have done such a thing!’

My father had a beautiful voice; he sang. Mama told him: Go into the priesthood. My father replied: ‘So, a batiar will become a priest?’ Said like a real stiliaga [hipster, beatnik]. He always wanted to be dressed fashionably. One of his colleagues wanted some ‘easy money’ and he became a Pole. But we and my father did not do that; we knew our own faith. We took potato pancakes to school in a cloth bag…

...In the winter, a group of Jews was brought from the ghetto to clear the snow from the road next to our house. And our neighbors, a bunch of them, are watching them. And my father says to my mother: Make lunch, and I’ll go to the German and ask him to bring them all for lunch, so that they are not taken back to the city. The German replied: ‘I’m handing them over to you, but if even one escapes, then none of you will remain alive.’ My mother boiled a whole pail of potatoes, and my father brought bread from the bread factory. They ate, then worked until evening, and then they were brought back to the ghetto.

One day in the springtime [probably 1942—Sh. B.] Jews from the ghetto in the neighboring town of Sasiv approached father with a request: They needed a place to conduct prayers at Passover. My father had a flour storehouse in Sasiv, and he removed everything from there, in order to give the Jews a place to pray [flour and all sour foods are forbidden to Jews during Passover—Sh. B.].

The KGB building was near our house [after the return of the Reds in 1944]. My father liked to drink, and when he walked home, they yelled, ‘Hands up!’ He says to them: ‘Raise them yourself. I can’t do it by myself!’ When our people saw that the Muscovites are drinking from glasses and ours from shot glasses, my father could not compete with them...

After the war, the neighbors laughed at us, saying that we had rescued Jews and stayed poor. They thought that way because other people had robbed Jews. In Pidhirtsi, people came and killed all the Jews for the gold that they left behind; only one little girl hid under a bed. Later some Jews came and beat the Ukrainians who had betrayed the Jews whom they had promised to hide for money.

Many left behind [Jewish] valuables and buildings. But we only had an old house.

To this day, there is a grain storehouse on Brodivska Street in Zolochiv, which was built with the red bricks of a ruined synagogue.

When the Jewish cemetery was being destroyed, figures and Jewish names were erased from some headstones, which were then placed next to the church bearing new names.

The Russians shipped my grandfather and grandmother to Siberia but later released them. After the war, the Muscovites beat my father and shouted at him, ‘You Banderite!’ [Ukrainian nationalist—Ed.]

My father said: ‘I don’t want anyone’s house. If we have a lot, they’ll ship us off to Siberia.’ My father did not want to take that building [owned by people who had been deported to Siberia after the war—Sh. B.]. The neighbors were not nice; they were afraid that we would take their large building away from them.

But there was a man who chauffeured the head of the raion executive committee. Everyone knew that he was a thief; he robbed people and lined his pockets. But everyone kept quiet.”

Afterword

By the time of the liberation in the summer of 1944, only ninety people—only one percent—out of the prewar population of nine thousand Jews in Zolochiv survived by hiding in bunkers, sewer systems, and pits in the forest, like wild animals. Of these ninety individuals, one in three was saved through the efforts of the Levytsky family. And this proportion perhaps most clearly attests to the feat of this family.

The website of Yad Vashem states: “The Lewickis were inspired by deep compassion and Christian love, and never expected anything in return.”

I have a question for Yad Vashem: Why did the entire family obtain the title of Righteous Among the Nations, except for the batiar Petro, Yaroslava’s father, who also helped to rescue Jews?

To return goodness for goodness is an important principle of Jewish morality. Therefore, I, as an Israeli, am proud of the fact that my country took care of Mrs. Levytska.

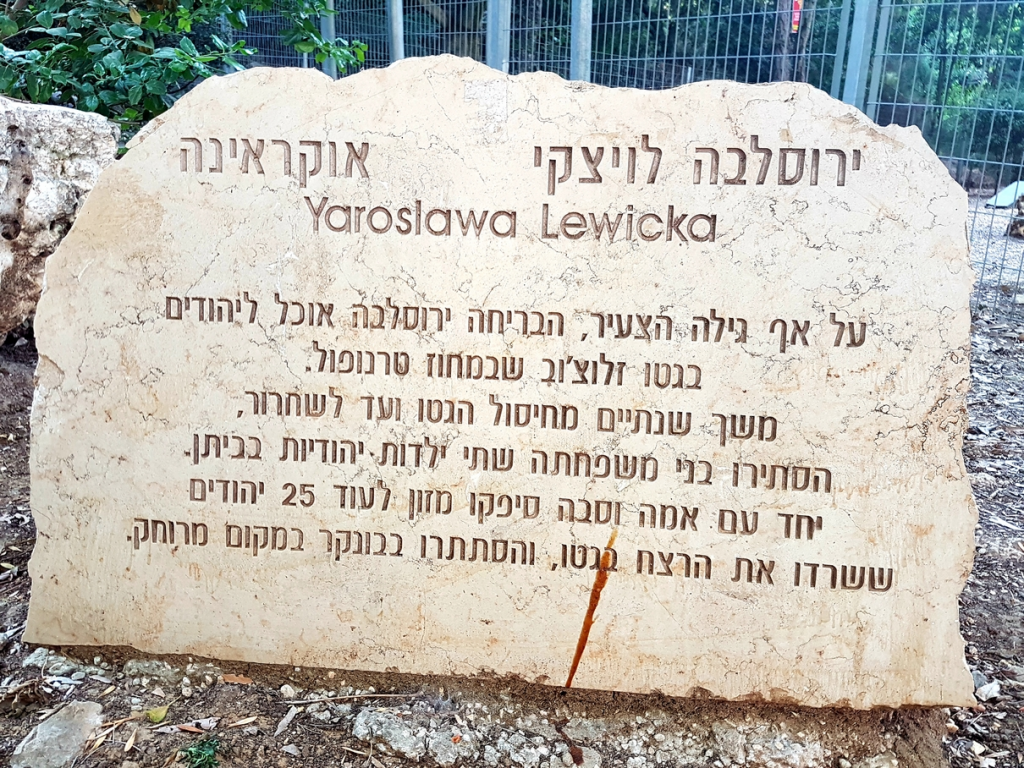

In Haifa’s Garden of the Righteous, where eighteen memorial stones bearing the names of saviors of Jews who once lived in the city (including Raoul Wallenberg), Mrs. Levytska is the only person to be honored with this commemorative marker during her lifetime.

Haifa knows and respects the modest heroine, who was born in Zolochiv. Perhaps the time has come for the Zolochiv municipal council to do the right thing and commemorate the name of the Levytsky family in a dignified fashion and name one of the city streets in its honor.

Text and photos: Shimon Briman (Israel).

Translated from the Ukrainian by Marta D. Olynyk.

Edited by Peter Bejger.