The fate of Hofshteyn, like that of the majority of Shevchenko’s Yiddish translators, was immensely tragic: They were shot in 1952—Oksana Pashko

On this Encounters program, we talk about Taras Shevchenko and the interpretations, translations, and elucidations of his Yiddish translators.

Our guest on the show is Oksana Pashko, a literary specialist, Candidate of Philological Studies, lecturer at the Department of Literary Studies of the National University of Kyiv Mohyla Academy, a literary specialist of the 1920s and 1930s, and the editor of Shevchenko Taras: Kobzar; Vybrani tvory; vydannia-bilinhva [Taras Shevchenko: Kobzar; Selected Works, Bilingual Edition].

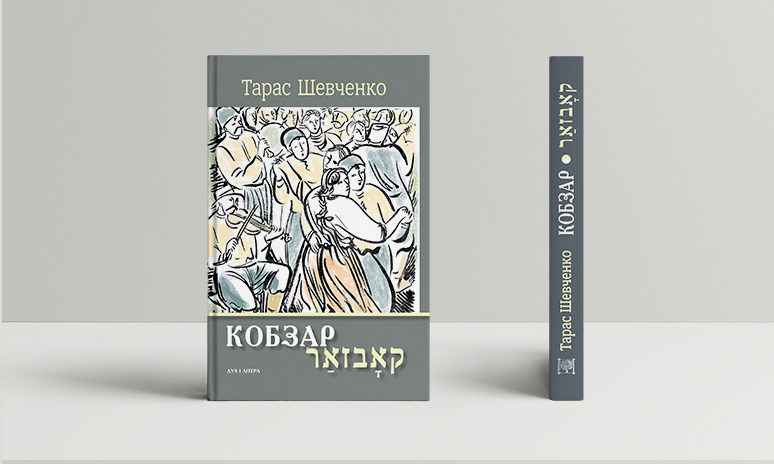

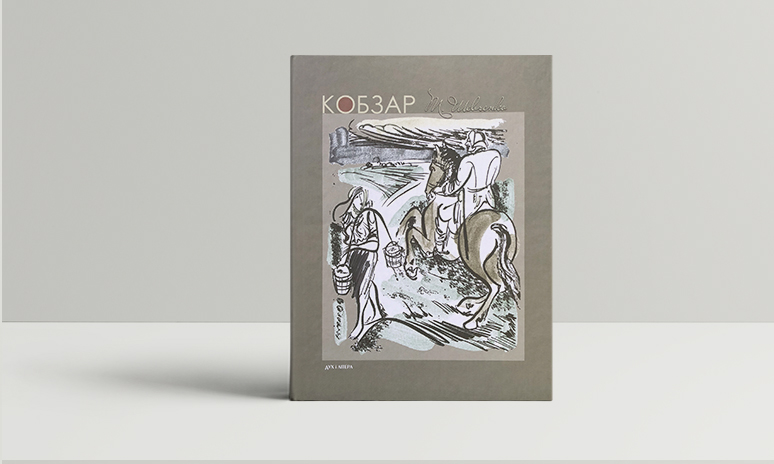

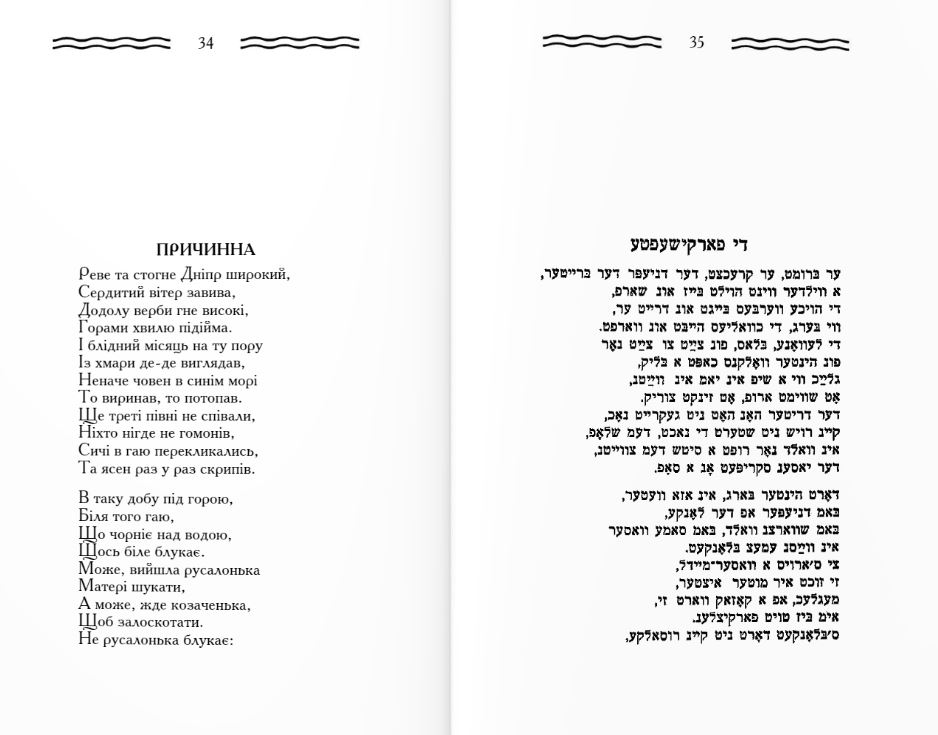

This book is a bilingual edition of selected works from Taras Shevchenko’s Kobzar. All the Yiddish translations were done in the 1920s and 1930s by the famous Jewish poet Dovid Hofshteyn (1889–1952). The illustrations by the “Boichukist” painter Vasyl Sedliar (1899–1937) were featured in the unique 1931 edition of the Kobzar.

Vasyl Shandro: When we talk about Taras Shevchenko and his translations into Yiddish, is it possible to sketch some kind of history, and does it predate the 1920s?

Oksana Pashko: It is natural to speak of the old history of Shevchenko translations, at least the dialogue, reworkings, and borrowings from Shevchenko by Jewish writers. All this began in the late nineteenth century and flourished at the beginning of the twentieth.

We must talk about such poets as Osher Shvartsman, Dovid Hofshteyn, Leyb (Lev) Kvitko, Perets Markish, and many other authors who worked on translations of Shevchenko in the 1920s and 1930s. Very few manuscripts have been preserved. The 1920s–1930s was a fantastic period about which we know less than about the nineteenth century. The memory of this period has simply been excised.

Starting in the late 1930s, the fundamental position was to forget everything that had happened in those years. Today we are working with fragments, the tips of icebergs that have been preserved in the archives. I think that there are many discoveries ahead of us.

Vasyl Shandro: What do we know about the history of the translations that were done in the 1920s and 1930s? Are we talking about one-time, random, and spontaneous translations that were published in periodicals, or about systematic work and large-scale publishing projects?

Oksana Pashko: The project that was carried out most fully in 1939, pegged to the 125th anniversary of Shevchenko’s birth, was a major event. This was a very pompous and collaborative celebration of Shevchenko with a Soviet accent. During this period, many translations in various languages, including Yiddish, were finally published.

Essentially, we are talking about three texts. One is Shevchenko for children, which was published in Odesa. Then there was the Russian text A Walk with Pleasure and Not Without a Moral, which was translated by Hofshteyn. And then selected poetry; this is what Dukh i Litera Publishers issued in 2019 under the title Taras Shevchenko: Kobzar.

Furthermore, according to archival data, many more works by Shevchenko were translated, but where they are is not known. There’s a very tragic story there. Editors and compilers were replaced because over a twenty-year period, many were simply arrested. As of 1930, we had only Hofshteyn’s translations. There is no answer to the question of the how and why of this selection.

Dovid Hofshteyn was undoubtedly one of the most important Jewish poets writing in Yiddish during the first half of the twentieth century. He began writing in the late 1910s. There was a “Kyivan group” comprised of Hofshteyn, Kvitko, and Markish. They collaborated very fruitfully with the Ukrainian intelligentsia. He worked in the modern manner and often experimented with form. He even used blank verse where Shevchenko did not; he modernized Shevchenko for a modern audience.

The fate of Hofshteyn, like that of all of Shevchenko’s translators, was immensely tragic: You will see that for nearly all of them, the date of death is 1952. These are repressed writers. I am talking about the so-called case of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee. They were all arrested in 1948 and shot in 1952.

At present, very many of Hofshteyn’s texts have been translated into Ukrainian. While he was alive, he was translated by [Pavlo] Tychyna and [Maksym] Rylsky, but here friendly relations were at play. We can look at a work entitled Taras Shevchenko v interpretatsiї ievreis′kykh pys′mennykiv [Taras Shevchenko in the Interpretation of Jewish Writers].

Vasyl Shandro: How close was this relationship, especially among the members of the writers’ circle?

Oksana Pashko: They were friends, they did a lot of joint projects. They even lived together; it was a shared literary life. Let us recall the Slovo building in Kharkiv and ROLIT in Kyiv (an acronym based on the words “Kooperatyv Robitnyk literatury” [Worker of Literature Cooperative], a residential building for writers built in 1934 in Kyiv, on Lenin Street, now called Khmelnytsky Street, no. 68—Ed.). Many Jewish writers, including Hofshteyn, lived there. They worked together, they translated each other’s works, they worked in a common cultural environment.

Vasyl Shandro: You are also the editor of the publication Taras Shevchenko, Kobzar: Selected Works; Bilingual Edition, which was issued in 2019 by Dukh i Litera Publishers. Does it replicate the 1939 edition to some extent?

Oksana Pashko: This is a unique publication because we have the original text of Shevchenko’s Ukrainian texts and a Yiddish translation. It is like a mirror that meets somewhere in the middle, where one text flows into the other. Someone who knows the two languages can enjoy the comparison of these two texts and the interpretation of one culture understanding another. Many of Shevchenko’s texts are inspired by the Bible.

What is also unique is that the publication is illustrated by the drawings of the Boichukist Vasyl Sedliar (a Ukrainian monumentalist painter, graphic artist, art critic, and pedagogue, who belonged to the creative group of “Boichukists” and was a victim of Stalinist terror—Ed.).

Work on the translations of Shevchenko predated the state’s desire to republish and interpret Shevchenko Soviet-style. Hofshteyn himself said that he began translating Shevchenko in the 1920s. These works were used in Jewish schools.

Vasyl Shandro: To what extent was this dialogue of cultures productive and constructive in the sense of translations from one language to another and the reverse?

Oksana Pashko: Translations of Shevchenko are among the projects that were addressed by Jewish writers. At the same time, Ukrainian writers translated a lot of Sholom Aleichem, Hofshteyn, Markish, and Kvitko. There was immensely powerful internal communication, even though the languages were vastly different in terms of structure and syntax.

Vasyl Shandro: Can we speak of a certain shelf of republished works by Jewish writers from this period, the 1920s and 1930s?

Oksana Pashko: Definitely. Hofshteyn was published in the Ukrainian language; a large corpus of translations was issued in 2012. The book is called O bilyi svite mii [Oh, World of Mine...]. These are Hofshteyn’s works, interpreted not only by Rylsky and Tychyna, but also by [Hryhoriy] Kochur, [Mykola] Lukash, Lina Kostenko, and Valeria Bohuslavska. We also need to talk about the Anthology of Jewish Poetry, a panoramic selection of Jewish poetry of many writers who lived in Ukraine.

This program is created with the support of Ukrainian Jewish Encounter (UJE), a Canadian charitable non-profit organization.

Originally appeared in Ukrainian (Hromadske Radio podcast) here.

Translated from the Ukrainian by Marta D. Olynyk.

Edited by Peter Bejger.

NOTE: UJE does not necessarily endorse opinions expressed in articles and other materials published on its website and social media pages. Such materials are posted to promote discussion related to Ukrainian-Jewish interactions and relations. The website and social media pages will be places of information that reflect varied viewpoints.