The Janowska concentration camp: What we know and don't know

The Janowska (Ukr. Yanivsky) concentration camp is a blank spot in the history of Lviv and the Holocaust on the territory of Ukraine. It has become obscured within the context of Eastern Europe and the better-known Auschwitz-Birkenau, Treblinka, Sobibor, and Majdanek, the concentration camps that became true symbols of the Shoah in Europe. For a long time, this topic was taboo in our country. Jewish victims were not placed in a separate category but were added to the general number of civilian victims. Serious research was launched only after independence was won. In historiography, there are ongoing discussions around this camp. The key problem is the lack of sources, above all German ones, which of course were destroyed.

The creation of the camp

The creation of Janowska is linked to the German occupation and the Germans' need to exploit unpaid Jewish labor. According to various data, 160,000 Jews were living in Lviv at the time. This was the third-largest urban community in prewar Poland.

Janowska would later become one of the centers of the Final Solution to the Jewish Question. However, this task emerged only once the camp came into being.

A key role in the camp's creation was played by Odilo Globočnik, SS Leader of the District of Lublin, who dispatched his representative to Lviv in order to select a site for the future concentration camp, slated to be a forced labor camp. A site on Yanivska Street was allocated by Yurii Poliansky, the starosta [head of the local administration] of Lviv. Storage facilities belonging to the Jewish industrialist Steinhaus were located here, and the site was adjacent to the Klepariv railway station. Thus, it was an ideal place for creating a camp. In July, workshops for repairing military equipment were set up here. They were a link in an entire conglomerate of enterprises that existed in the SS system, the first of which were established on the territory of Germany and occupied Poland in 1939 and which existed mostly in Dachau, Sachsenhausen, Buchenwald, Auschwitz, and Majdanek.

What do we know about the existence of these workshops in the first months after they were created? They employed workers who were still not fixed to this place, so to speak. They could return home after work. They were even issued food packets and were paid for their work. Naturally, the pay was meager, but many Jewish laborers attempted to get a job in these workshops and obtain a certificate, completely unaware of what fate had in store for them. At the time, between three hundred and five hundred laborers, Jews as well as Poles, worked here.

The turning point in the history of the camp came at the beginning of October 1941. We have no clear documentary evidence of its founding date, but, as many survivors recall, in early October, the camp commandant Fritz Gebauer summoned everyone together and said that they would remain here from now on. In a matter of hours, the security guards from the workshops enclosed the area with barbed wire and built observation towers with searchlights on the sides. This put an end to the external contacts of the people in the camp. Initially, there were no barracks, and the prisoners of the newly created camp lived in the workshops or on the street. Neither were there such basic necessities as toilets and baths. We know that on 1 November 1941 a sign was affixed to the camp gates announcing that this was the Lemberg forced labor camp, subordinated to the SS and the police of the District of Galicia. The authors of some studies believe that this is the date the camp was established.

At this time, freelance laborers were still working in these military workshops. We even have information about highly qualified Jewish workers who were allowed to return home.

In the winter of 1941–42, the camp experienced its first great crisis: a typhus epidemic that killed nearly three hundred prisoners. We know that as of early March 1942, there were only two hundred people in the camp.

Administration of the Janowska concentration camp

The camp administration managed the life and death of the large number of people who ended up in Janowska. The camp was run by a commandant, to whom up to fifteen officers and sixty to eighty rank and file SS men reported. The first commandant was Fritz Gebauer, who was in charge of the workshops from the summer of 1941. Before the war, he was an employee of the Siemens company. Outwardly, he seemed to be a pleasant person, but, in reality, he was a brutal sadist. During a peaceable conversation with a prisoner, he would suddenly grab the man's neck and start to choke him. Owing to this habit, he was nicknamed the "Choker." After this type of incident, he would become a seemingly intelligent individual once again.

Besides choking, he had several other methods for killing prisoners. Gebauer buried prisoners alive, and he forbade prisoners to wash but demanded ideal cleanliness of them. According to testimony dating to the winter of 1941–42, he forced naked prisoners during a severe cold spell to wash in a barrel filled with water; they died after this. We also learn from memoirs about a case where he threw several prisoners into a cauldron in which a thin soup was boiling and covered it with a lid. Gebauer became known as the formulator of the principle of collective responsibility in the camp. For any disciplinary infraction, the Germans meted out severe punishments, including death. After the war, he was sentenced to life imprisonment, and he died in 1979. He is regarded as the originator of the sadistic regime that existed in Janowska.

However, some researchers question the dating of the forced labor camp's existence to the period prior to March 1942. For example, the American historian Waitman Breon insists that the camp was created only after the arrival of Gebauer's successor, Gustav Willhaus. The latter arrived in March 1942 in the capacity of deputy, and his formal appointment took place only in July 1942. He was tasked with expanding the forced labor camp and separating it from the military workshops.

In appointing Willhaus, the SS and police leader in the District of Galicia [Fritz] Katzmann had an ambitious plan. He wanted to establish a large camp that he could boast about to [Heinrich] Himmler. Willhaus began setting up the camp, building barracks and the entire complex, which triggered a conflict with Gebauer. There were perpetual arguments about the prisoners, building materials, and belongings. Some historians believe that it was a single complex, while others say that there were two distinct structures. The situation was not pleasant. Willhaus was more interested in transforming the camp into a concentration camp, while Gebauer viewed it in terms of increasing military production. Despite the fact that the prisoners lived in the camp, nearly half of them were assigned to the workshops. The situation is illustrated by the following comic episode: Willhaus named his dog "Fritz," in honor of his neighbor, and constantly scolded the dog.

Many prisoners recall that Willhaus loved horseback riding, and he was an avid art lover. He became famous for building a villa in the camp, from the balcony of which he entertained his wife and nine-year-old daughter by shooting at prisoners. Some eyewitnesses recall that Nazi officers and their wives were present at this bit of "fun." According to evidence presented by the Soviet side during the Nuremberg Trials, Willhaus, on his daughter's birthday, ordered two four-year-old children to be tossed into the air, and then he shot at them. Of course, these testimonies are not reliable sources, but the facts relating to the shootings from the balcony appear in many recollections. What was his further fate? In July 1943, he was made an officer of the Croatian Volunteer Division of the Waffen SS and was killed on the Western Front in March 1945.

A major role in developing the camp was played by Deputy Commandant Erwin Richard Rokita, who was a Pole by birth and a member of the SS since 1932. He introduced the strict division of workers' brigades in the camp, which would go to the city and toil in the workshops. Rokita's notoriety rested on his sadistic invention, known as the "Tango of Death." He was a music lover and had played the violin in a jazz band in Katowice; that was his weakness. He organized a camp orchestra that was composed of Lviv's finest musicians and composers (according to various data, there were forty members). This was the Janowska camp's "calling card." But, like other SS officers in this camp, he was a sadist. He would cry during performances, but if he heard a single false note, the performer would be put to death. The brigades performed when the prisoners left the camp for work and when they returned. The "Tango of Death" was a melody composed especially to be performed during executions. During his trial in Stuttgart in 1964, Rokita was sentenced to a nominal term of five years.

The last commandant was Friedrich Warzok, who arrived in July 1943 and remained in this post until July 1944.

The camp's internal structure

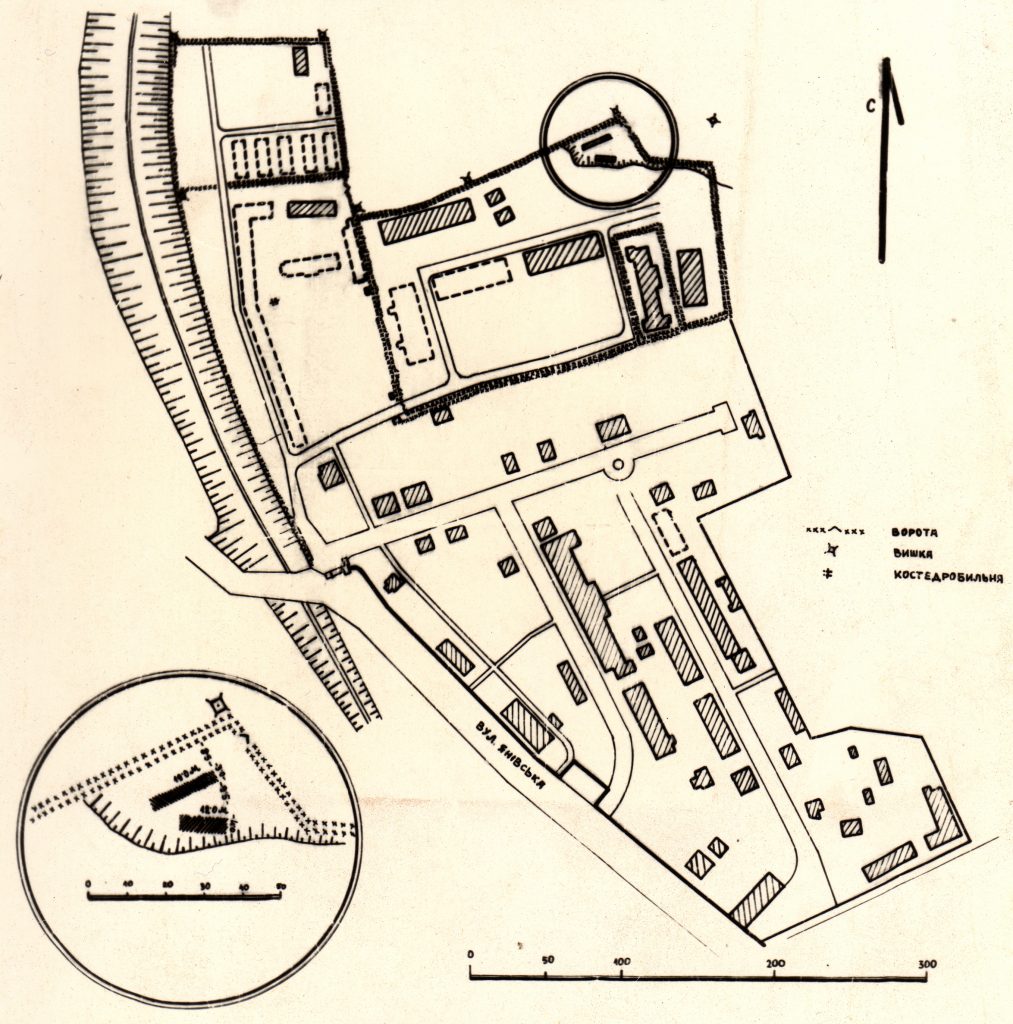

The camp was spread over an area measuring 3,000 sq. m. and was divided into three zones. It consisted of thirteen barracks (nine, according to other sources), workshops, storage facilities, and administrative buildings. The area was enclosed by a concrete wall, the top of which was strewn with shards of broken glass. One section housed military workshops, where the prisoners worked. The administrative buildings and the commandant's villa were in the center of the compound. Behind the line of barbed wire were the barracks as well as the bathhouse for the camp officials, the sewing workshops, and other small workshops.

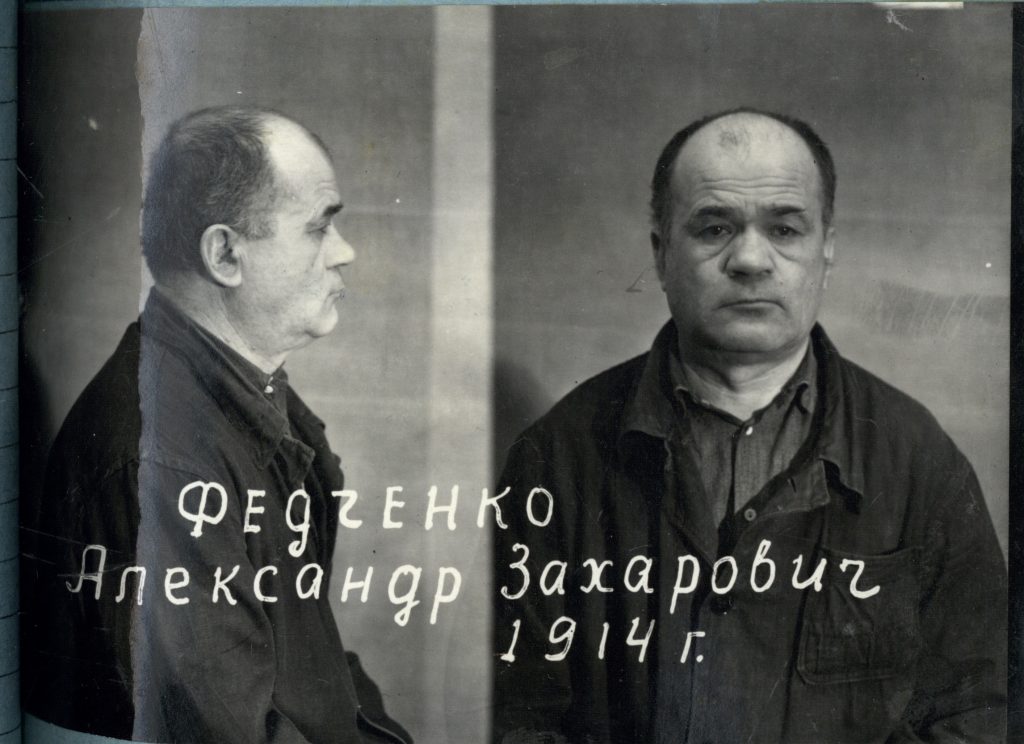

Initially, SS and SD units, as well as Ukrainian policemen, provided security for the camp. The camp also had a Jewish police force. But in 1942–1943, the Germans recruited vakhmans [Ger. Wachmänner], Red Army prisoners of war, who were trained to shoot prisoners or maintain order in the ghettos and concentration camps. Many researchers describe their exclusively Ukrainian background. But having had the opportunity to work with the documents of the Soviet secret services that conducted the investigation, I have acquired new data. Based on this KGB sample, out of 65 arrested vakhmans, 30 were Russians, 29 were Ukrainians, 3 were Tatars, 1 was Belarusian, 1 was Bulgarian, and 1 was German. Thus, there were Ukrainians among them, but they were not predominant, and their numbers were equal to the Russians. Of course, this composition differed from camp to camp. Perhaps in Lviv, prisoners might see mostly Ukrainians. But we have evidence pointing to the presence of both Russians and Tatars in Janowska. The form of collaboration does not have a national coloration. In fact, the fate of these people was tragic. We have photographs of vakhmans who were arrested after the war, tried, and even executed. They were prisoners of war, who were faced with a choice between cooperating with the Germans or dying in the camp from starvation or exhaustion. Some people accepted the proposal to collaborate. This was for them a chance to survive, but there was a price for this survival, as they had to assist in the implementation of the Holocaust. But witnesses have described that in terms of their abuse and sadism, they were as bad as the Germans.

About the prisoners

The original purpose of the camp was the concentration of the civilian—mostly Jewish—population, in order to exploit it for forced labor. Jews were arrested during roundup operations in the city. However, we also have testimonies indicating that among them were Ukrainians, Russians, and Poles who had been arrested for petty crimes against the German occupying authorities. They received mostly short sentences: up to six months. According to different estimations, approximately two hundred thousand people were incarcerated in the Janowska concentration camp during the period of its existence. These are Soviet estimates, and this figure has sparked many arguments among historians. [Filip] Friedman, who was one of the first to write about the Holocaust in Lviv and the Janowska concentration camp, gave the figure of three to four hundred thousand people, which is an absolutely implausible number.

Despite the fact that there were prisoners of other nationalities in Janowska, this camp housed mainly Jews and was an integral link in the Nazi policy of the Final Solution to the Jewish Question.

We have interesting testimonies from a prisoner named Bohdan Kokh. He recounted how he escaped while being transported for work in Germany, as a result of which he ended up in Janowska. According to his statements, Ukrainian prisoners were told immediately that "associating with Jews was banned under threat of execution." Further, "Jews were brought out of the zone to work; we, Aryans, were not; it was forbidden." Thus, according to him, Ukrainians were not part of the brigades that were comprised of Jews; they lived in separate barracks and tried their outmost to distance themselves, The situation of non-Jews was much easier.

A variety of badges designated for different nationalities was worn on clothing in the camp. Jews had yellow badges, Ukrainians—blue, Poles—red, and Russians—green. However, there are few testimonies about Russians, for example. The population of the camp was not stable, as a large number of people came through the camp who had been convoyed from various places of detention in Galicia: from Peremyshl, Zhovkva, Sudova Vyshnia, Mostyska, Yavoriv, Rava-Ruska, Kamianka-Strumylova, Sambir, Drohobych, Berezhany, Stanyslaviv, Horodenka, Kalush, Boryslav, Dolyna, Deliatyn, etc. This is a large number of Galician cities and towns from which deportations of Jews took place. For a certain period of time, they were incarcerated in Janowska.

We also know that in late 1941 the camp housed a group of Jews who had been deported from Austria and the former Czechoslovak state, and in the winter it held Jewish citizens of the U.S., Belgium, France, England, Holland, Hungary, and Yugoslavia, who had ended up on the territory of occupied Poland and were living in Lviv at the time. Unfortunately, there are very few testimonies about them, so we do not know their numbers and where these people had come from.

A sharp increase in the number of prisoners took place throughout 1942. Over the course of the year, an entire concentration camp complex for ten thousand people was built. The number of prisoners reached its peak in March 1943, when, according to various estimates, the camp held between fifteen and thirty thousand people. This period saw the creation of a women's section, where four hundred prisoners were held.

The prisoners belonged to various social groupings. The most privileged were employees of the camp office, elders [starostas], work managers, and Jewish policemen. They enjoyed some authority that was, of course, limited by the Germans, but they enjoyed the most privileges. The middle stratum consisted of professionals and specialists who were employed in the workshops: engineers, technicians, mechanics, and people engaged in industry. The lowest stratum was comprised of workers, the majority of whom were from the intelligentsia: lawyers, functionaries, teachers, writers, musicians, and physicians. Sometimes they had to perform very degrading types of jobs, like cleaning toilets. These prisoners had the lowest status: They were subjected to torture and abuse and assigned to heavy manual labor, which led to their speedy demise.

Camp life

After arriving in the camp, the prisoners went through a painful and humiliating inspection during which all their belongings, except clothing, were confiscated. Then they were sent to the barracks. The camp regime fueled the attrition rate of death of the prisoners. The food rations consisted of a glass of ersatz coffee in the morning and a bowl of balanda [watery soup] with some dirty, rotten beets and potatoes floating around, and 150–200 grams of bread. Sometimes the balanda was so disgusting that the prisoners refused to eat it, even though they were starving. There were even fatalities following such meals. The quality of the bread was horrendous: raw and sticky. Nevertheless, any scrap of food was a great treasure in the camp because starvation was a huge challenge for the prisoners. Owing to this diet, the prisoners often did not survive for more than two or three months. A particularly high level of starvation marked the last months of 1942 and the first half of 1943 when prisoners did not survive for more than five or six weeks. The entire camp was serviced by a small kitchen, next to which there was always a long line of prisoners.

The black market, which existed thanks to food packages from the ghetto, helped the prisoners survive in the camp. Trade was established by the prisoners themselves, and the most favorable locations for this were the toilets because there was less control there. The goods available in this black market included a tablet of saccharine, half a handful of bread, a thin slice of sausage, a clove of garlic, or half or a quarter of an onion. Such were the realities of camp life. A communication channel operated via self-employed workers from the city who were employed in the workshops. They were Poles and Ukrainians, who took advantage of the situation to sell goods to the Jews at an exorbitant price. At first, packages from the ghetto were permitted, but at a certain point, the Germans banned them and began to confiscate them. Besides starvation, the prisoners suffered from the backbreaking work and constant nervous stress and terrorization. The only opportunity to be alone was sleep, which was scheduled from 10:00 p.m. to 5:00 a.m. But even during lights-out, night watches or death runs were carried out, as well as a practice called "vitamin taking," one of the methods of violence applied in the camp.

The prisoners rose at 5:00 in the morning and rushed off to wash. They had to stand in a long lineup, and not all the prisoners managed to wash.

The wooden barracks were dirty, and for some time, they were not cleaned. However, after the typhus epidemic, Willhaus carried out a large-scale disinfection, which was subsequently done on a regular basis. Once a week, there was a march to the bathhouse, but this was a form of torture because the guards tried to organize various competitions. For example, they would order the prisoners to get dressed in sixty seconds. Anyone who failed was shot. Prisoners also recounted stories about the extremely hot or extremely cold water.

The problem in the camp was the unsanitary condition. Medical care, as such, did not exist. In the winter of 1941–42, a hospital was set up, but it provided no medications or real care. The same thing could be said about the permanent hospital that was created later. The "most effective healing" was shootings. SS men periodically entered the hospital and took away prisoners. In June 1942, 180 sick Jews were executed in the camp. Prisoners were forbidden to be sick, and unwell prisoners tried their utmost to conceal their illnesses.

In Janowska, we also see an example revealing that forced labor was not so much effective as exploited in order to kill off prisoners. The workday lasted between twelve and fourteen hours. The prisoners were assigned either to the workshops or worked at a great distance from the camp. Those who stayed behind were the most susceptible to being terrorized. Spotted by sadists, they often fell victim to various types of arbitrary behavior. The prisoners performed labor at various German enterprises. One group worked on the railway, another did roadwork or serviced internal communications of buildings. There were also sanitary brigades in the city. Those prisoners who worked in the city had a chance to make contact and barter articles for food and thus had a better chance of surviving. There were also escape attempts. The composition of the brigades was changeable; different prisoners were allocated every day.

Janowska is regarded as the second-largest concentration of prisoners performing forced labor in Europe, after Majdanek. Prisoners returning from work often carried back the bodies of their dead comrades. After the workday ended, they were forced to carry out absolutely meaningless work called "vitamin taking": hauling boards, bricks, and logs.

Those who could not endure this heavy work were led behind the barbed wire, where they were shot or simply expired. Up to 130 prisoners could die as a result of one such "vitamin taking." This practice existed until the summer of 1943.

Speaking of everyday terror, I would like to cite a phrase that was uttered by a prisoner and simultaneously used by Michal Maksymilian Borwicz, a researcher specializing in the Holocaust and the Janowska concentration camp, who regards this camp as a kind of university of violence, a higher school of sadism. He is convinced that the biggest sadists of the German death machine were concentrated there. According to Borwicz, Janowska was a supplier of killers, at a minimum for the District of Galicia. We know that SS officers later came to occupy various positions in the camps and the ghetto on the territory of Galicia, and they were the ones who exported this extreme violence to other places.

Choice sadists and various scum of the Nazi death machine were in the Janowska concentration camp. Many of these people suffered from pathological perversions, and prisoners described what went on there as "hell on earth." This phrase appears in many recollections.

The most diverse ways of killing people were used in this camp. Each Nazi tried to outdo his colleagues by discovering his own special killing method.

The day began with an inspection that culminated in mass beatings and shootings of prisoners. The weak, the sick, and those who had violated discipline were either shot on the spot or brought to the area between the two barbed wire fences, where they were shot or simply expired. Death runs were also carried out. This meant that a large group of condemned prisoners had to run the gauntlet of SS men, who tripped them with their legs or carbines, beat them over the head, shot at them, etc.

There were two gallows in the camp. One of them was for prisoners who wanted to commit suicide. Every day the prisoners were subjected to abuse and beatings for no reason. There is evidence indicating that every day nearly a hundred corpses were piled on the garbage dump next to the kitchen. In other words, this was a daily, systematic killing of people, but the methods used were quite different. Special methods were used to kill women, and we have testimony about sexual violence and crimes in the camp.

Each officer had his preferred method of killing. For example, Rokita killed sixty people every day before breakfast. Willhaus, as mentioned earlier, shot people from his balcony. On 20 April 1943, in honor of Hitler's 54th birthday, he selected 54 prisoners and shot them. Interestingly, Simon Wiesenthal, who became a famous Nazi-hunter after the war, was supposed to be among the prisoners fated to die that day. According to his account, he escaped death because at the time he was working on a poster for Hitler's birthday, which was supposed to be hung at the railway station. The next commandant, Friedrich Warzok, loved to kill prisoners by hanging them by their legs.

The Ukrainian prisoner Bohdan Kokh recalled: "The most terrible day was the last one, when twenty-five thousand Jews were shot [...] This operation ended with the last orchestra coming to the pit; they were undressed, they laid down their instruments; they went into the pit, but before that they played the 'Tango of Death' for themselves." Unfortunately, the notes of this melody did not survive.

Janowska as a transit camp

Starting in March 1942, Janowska was also used as a transit camp. This happened as part of Operation Reinhard, which was carried out on the territory of the Generalgouvernement [German-occupied territories of central Poland—Ed.] the goal of which was to liquidate Polish Jews (over two million people). Lviv and the Janowska camp were an integral part of it. It is precisely this operation that connects Lviv with the tragedies that took place in such camps as Bełżec, Sobibor, and Treblinka, where Jews were deported. The Jews of Lviv were among the first victims.

The first large-scale Aktion [Operation], as it is known in German, was conducted in March 1942. It was led personally by SS Gruppenführer Fritz Katzmann. As a result, fifteen thousand Lviv Jews were sent to the gas chambers in Bełżec, where they were all killed. Before the Jews were dispatched to the gas chambers, they were sorted according to their fitness for work. Janowska was a key stopping point, where the sorting of Jews was carried out. This division of people into those who were to remain in the camp and those who would be sent to the gas chambers did not take place everywhere, but Janowska was one of these camps. First and foremost, women, children, people unfit for work, and the elderly were sent away. During the March operation, deportations from provincial Galician towns also took place. The path of these Jews went through Janowska. We know of cases where women and children spent one or two nights within an enclosed area, awaiting death without food and water. The first operations took place under conditions of strict secrecy, and few Jews were aware of their impending fate. After August 1942, information about the tragic fate of the deportees became more available. A large-scale operation, pegged to Heinrich Himmler's visit to Lviv, took place on 17 August 1942. Himmler also visited Janowska. For a period of twelve days, from 10 to 22 August, between fifty-five and sixty thousand Jews were detained in Lviv; the majority of them were sent to Bełżec. Lviv became the largest center from where Jews were dispatched in the summer of 1942 to the Generalgouvernement after they were removed from the Warsaw ghetto. It was led by the Janowska camp commandants Gustav Willhaus and Richard Rokita, which fact underscores the role of this camp and its leadership.

"Squeezed into one group of trembling people, we stood close together, almost one behind the other. It was stifling hot, and we were close to going mad. Not a drop of water, not a crumb of bread [...] We realized that we were going to die, that there was no salvation for us, we were apathetic, we did not make a sound. We were all thinking about one thing: how to escape, but there was no possibility [...] No one spoke to anyone, no one comforted the weeping women, no one stopped the children from crying. We all knew that we were going to a certain and terrible death."

From the memoirs of Rudolf Reder, who was sent to Bełżec along with other Jews but managed to survive.

A third operation was carried out in Lviv from 18 to 20 November 1942, during which ten thousand people were transported to the Bełżec death camp. The victims of the operation were Jews from the ghetto and from the camp itself.

It is interesting to note that Janowska became a regional hub for the delivery of clothing and personal belongings of Jews who had been killed. In 1944 a Soviet commission discovered eleven thousand pairs of men's, women's, and children's shoes in the camp.

Naturally, there are testimonies about escape attempts. For the majority of prisoners, they ended tragically. Those who succeeded in escaping returned to the Lviv ghetto. After Bełżec ceased to exist as a death camp in late 1942, deportations took place mostly to Sobibor and Treblinka.

Janowska as a mass killing center

According to a much-repeated claim, Janowska became an extermination camp starting in 1943. However, in his latest work, Waitman Beorn states that, given the daily acts of terror and mass killings in the camp, it had been an extermination camp since it was established. At issue are two murder sites: the area of the camp called Pisky [Sands], which the prisoners called the "valley of death," and Lysynetsky Forest, where on some days up to three thousand people were shot. The victims were of different nationalities: Ukrainians, Poles, and Russians, but the majority were Jews. There is evidence that Dutch and French prisoners of war were executed at Pisky in November 1942. The shootings were unexpected, and no one tried to escape. A deep pit was dug, and the guards ordered the victims to strip and line up along the edge. Then, the shooting started, and the corpses fell into the pit. When the executions were over, the corpses were covered with earth. One of the largest operations took place on 22–25 May 1943, when, according to various sources, between 6,500 and 7,500 Jews from the camp and the ghetto were killed.

A Soviet commission studied sixty sites where camp prisoners were killed and determined that the number of victims was two hundred thousand people. This figure is the subject of discussion in historiography because the estimating methodology is unclear. Contemporary researchers cite a figure ranging from forty to eighty thousand. The current state of sources does not allow us to determine the exact number of victims.

Sonderkommando 1005

With the help of Sonderkommando 1005, the Nazis tried to conceal the traces of their crimes in Janowska. These work units [comprised of Nazi death camp prisoners] began operating in the camps located on the territory of Poland. In April 1943, the Germans discovered the burial place of the victims of the Katyn tragedy [the mass execution of Polish military officers and intelligentsia by the Soviets in 1940—Ed.] and used this in their propaganda. This also gave them the opportunity to think about how someone might discover their crimes.

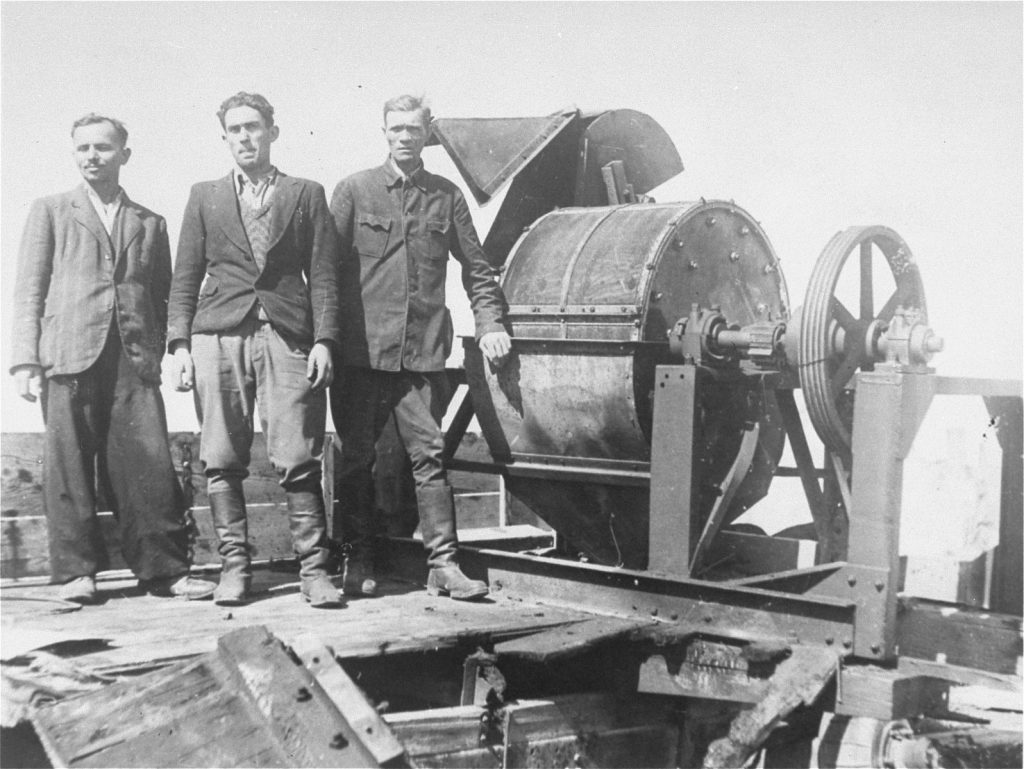

In order to cover up the traces of the mass killings, they created in July 1943 Sonderkommando 1005, a death brigade in Janowska. It was composed of 126 individuals, who carried out exhumations, cremated corpses, and ground up the bones of the dead at the sites of mass shootings. This unit handled not just old corpses but also the bodies of prisoners who had been killed before their very eyes. After completing its mission, the brigade was shot in Lysynetsky Forest.

The liquidation of the camp

In September 1943, there were nearly seven thousand Jews in the camp, as well as 225 people of other nationalities, mostly criminals. Warzok, the new camp commandant, tried to create the impression that the camp regime was becoming more humane, in order to dupe the prisoners about their eventual fate. At the same time, however, owing to the situation on the front, the Germans sought to put an end to the Jewish question, and a deadline was set for late November 1943. Some prisoners found out about this and began preparing an escape plan. Testimonies reveal that on the eve of the camp's liquidation, on 18 November, during the departure for work, one group of underground members attacked the guards near the gates, while another launched an attack next to the guardhouse. They killed eight SS men and some vakhmans and seized their weapons. The Germans conducted a five-day operation, during which they shot the fugitives. We know that a group of 23 people was saved. This attempt to mount an uprising became the formal pretext for liquidating the camp. During the final operation, up to five thousand Jews were shot in "Pisky."

This did not mark the end of the camp's existence as it continued to operate in another format—as a forced labor camp, where nearly a thousand people were held. In April 1944, when Soviet planes were bombing Lviv, part of the camp was destroyed, and fifteen Jews managed to save themselves. The rest were evacuated to the West in July 1944, and during the foot march, many of them died.

21.12.2018

Oleksandr Pahiria

Originally appeared in Ukrainian @ zbruc.eu

Translated from the Ukrainian by Marta D. Olynyk.

Edited by Peter Bejger.

NOTE: UJE does not necessarily endorse opinions expressed in articles and other materials published on its website and social media pages. Such materials are posted to promote discussion related to Ukrainian-Jewish interactions and relations. The website and social media pages will be places of information that reflect varied viewpoints.