The Lviv pogrom, 101 years later

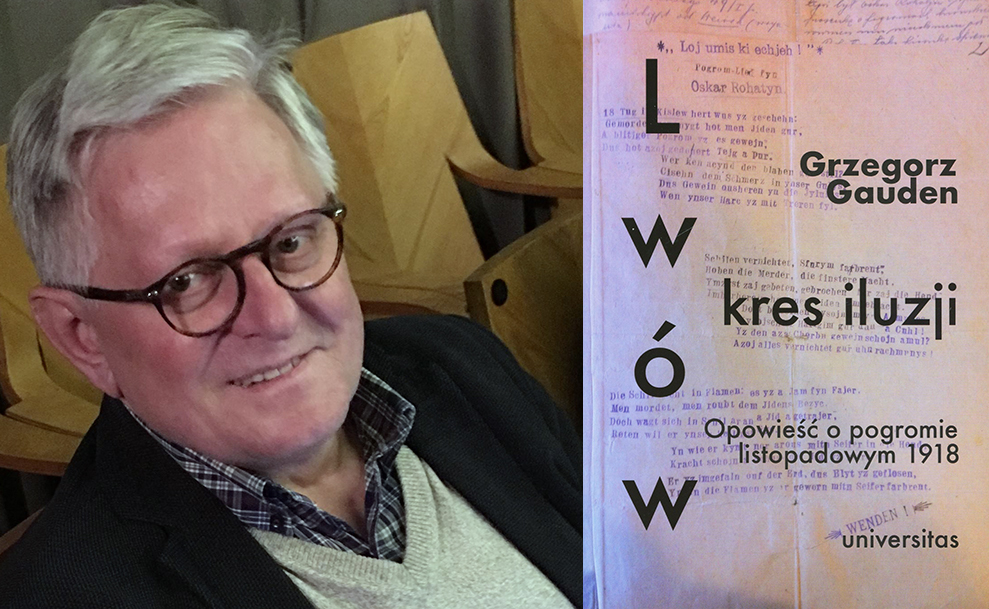

If last year, roughly around this time, early in the morning before sunrise, you saw an imposing gray-haired man in Lviv's center wandering pensively down the street, glancing at the clock, and looking around anxiously, you can be sure that it was Grzegorz Gauden. He was collecting materials for his book, and it was important for him to find out when and how dawn arrives in Lviv these days. But let's take things one step at a time.

There cannot be good without bad. That is the only way to explain the situation that occurred right after the PiS [Law and Justice] party came to power in Poland when it dismissed Grzegorz Gauden from his position as director of the Polish Book Institute. With an abundant amount of time on his hands, Gauden set about writing a book. I believe that if Polish government officials had known what kind of book Gauden would write, they would not have been in such a hurry to dismiss him but would have loaded him down with additional responsibilities.

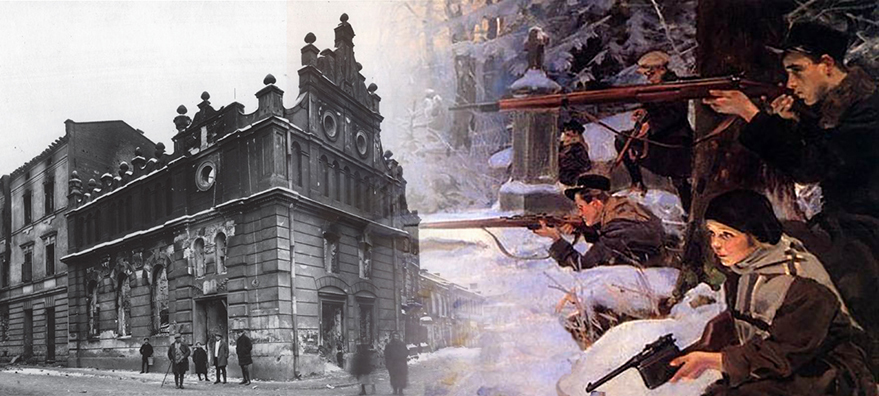

Because Gauden wrote a book about the Lviv pogrom of 22–23 November 1918, after the Ukrainian army had retreated quickly, and the city was occupied by Polish troops, after which early in the morning, before dawn, a hellish pogrom began in the Jewish quarter of Lviv. The book is called Lviv—The End of the Illusion. The end of illusions also resonates with Poles because of the end of Poland's eastern territories—at the very least, the end of the myth about the noble and heroic "liberation" of Lviv by the Poles in 1918.

Because Gauden wrote a book about the Lviv pogrom of 22–23 November 1918, after the Ukrainian army had retreated quickly, and the city was occupied by Polish troops, after which early in the morning, before dawn, a hellish pogrom began in the Jewish quarter of Lviv. The book is called Lviv—The End of the Illusion. The end of illusions also resonates with Poles because of the end of Poland's eastern territories—at the very least, the end of the myth about the noble and heroic "liberation" of Lviv by the Poles in 1918.

Lviv (Lwów) was the only Polish city to be awarded the highest military decoration, the War Order of Virtuti Militari. One of the central state myths of a reborn Poland is based on the famous "Lwów Eaglets," who defended and captured this city. Grzegorz Gauden's book puts this myth under the microscope, and behind the valiant facade, the reader discovers the skeletons of innocent victims of the pogrom, the faces of looters, and the image of the collective cowardice of the Polish middle class of Lviv.

Cowardice, because the attractive myth of the Eaglets, the teenagers and children who went to war for Lwów, also means that the adults did not want to fight and die. They preferred to hide in their townhouses, to maintain neutrality, so to speak, and wait until some force finally prevailed. And once it prevailed, to shift their malice onto the defenseless Jews (they were afraid of the Ukrainians because they had an army and might still return). And along the way, to warm their hands with Jewish property. It was not just criminal elements or drunken soldiers who were beating, killing, robbing, and raping in the Jewish district of Lviv, but also the local "cream of the crop": rich city folk, ladies in hats, and officers.

Gauden offers an unvarnished description of those three days: "The catalogue of methods for abusing the Jews in Lviv was lengthy: Jews were beaten on the streets, in prisons, and during forced labor. Their beards and sidelocks were ripped off. Jewish shops and kiosks were smashed; there were robberies and theft in apartments; women were raped; Jews were forced to jump on tables and benches; ransom was demanded; Jews were forced to dance for soldiers' entertainment; there were nocturnal hunts for Jews, who were used not only to perform labor in the army but also to work as servants for the wives and mistresses of officers. The elderly, as well as members of Lviv's intellectual elite of Jewish background—engineers, doctors, and lawyers—were forced to perform the most humiliating jobs. The Jewish cemetery was desecrated, and Jewish funerals were mocked" (p. 371).

But why just those three days? Gauden proves convincingly that only the most active phase of the pogrom lasted seventy-two hours. However, the abuse of Jews and the pillaging of their property lasted nearly to the end of the year—in other words, for six weeks. By his education, the author of the book is not a historian but a lawyer, and his narrative only benefited from this. All the facts were carefully amassed and developed, and his arguments are scrupulous and systematic. In discussing the Lviv pogrom, Gauden delves into the history of Eastern European pogroms and even provides a brief overview of the use of this term in historiography and jurisprudence.

This thoroughness is not superfluous because the author realized that this publication would provoke a flurry of criticism in Poland and cause a real sensation. Information about the Lviv pogrom in Poland was carefully erased, concealed, and hushed up. This began in the first days after the pogrom but continues to this day. The tone of the comments and reviews of this book by Polish right-wing radicals and some officials leaves no doubt that many people today do not want this bloodstain to pollute the heroic banner of the revival of independent Poland 101 years ago.

This book has been called anti-Polish, but, in my opinion, it is exactly the opposite. This is a publication by a real Polish patriot, one who wants to be proud of his state. That is why silencing crimes is humiliating for him. Gauden, the lawyer, demands that the perpetrators and executioners be named because until justice is served, the shadow cast by this shameful crime lies on the entire Polish state. The author defends the citizens of this state—after all, Poland was not and is not exclusively a country populated by a single ethnic group. In this context, Gauden's book is extremely relevant for our time and contemporary Polish politics.

"This is how the Polish idea of freedom for peoples and the self-determination of nations and Polish political messianism reached the form of its degeneration: extreme Polish national egoism that became the ideology of subjugation, ethnic hatred, and domination over other nations. Polish Catholicism became the religion of violence and the enslavement of other nations; the religion of hostility and disrespect of other confessions" (p. 556), writes Gauden about those November dawns in 1918. His categorical tone is understandable, for the unpunished crimes of the past are a prologue to hatred in our time.

Grzegorz Gauden collected the majority of research materials from Lviv archives, and when I was reading [his book] I was tormented by the following question: Why did Ukrainian historians not do this earlier? After reaching the last page, I understood that it had to have been written precisely by a Pole, and a Polish patriot to boot. That is the only way the book had a chance of being heard in Poland, so that the memory of innocent victims could be revived, if not expiated.

19.11.2019

Originally appeared in Ukrainian @ zbruc.eu

Translated from the Ukrainian by Marta D. Olynyk.

Edited by Peter Bejger.