The post-independence period should have benefited Ukrainian culture, but even functioning institutions have been ravaged — Oksana Boiko (pt. 2)

[Editor's note: Russia's unprovoked and criminal war against Ukraine suspended the regular work of many organizations, reorienting their efforts. So it is with the Ukrainian Jewish Encounter. In the coming weeks, we will run interviews and articles done before the beginning of the war, which reflect the myriad of interests undertaken by Ukrainian journalists, scholars and writers.]

The continuation of our conversation about synagogue architecture in Ukraine, its features, and the preservation of monuments that have survived to our time.

What are the architectural features of ancient synagogues? Did they have a defensive function? What was the impact of Ukrainian culture on them?

We discussed this topic and others with Oksana Boiko, Candidate of Architectural Sciences, associate professor at the Department of Restoration of Architectural and Artistic Heritage (Lviv Polytechnic National University), and academic associate of the Ukrainian regional scientific and restoration institute Ukrzakhidproiektrestavratsiia.

The form and features of synagogue decorations

Vasyl Shandro: In the previous program, you talked about the somewhat ascetic look of synagogue exteriors. Are we talking about certain types of synagogues, or is this cube-shaped, rather severe, outwardly unremarkable, and simple form typical? Are there any deviations?

Oksana Boiko: A synagogue is a functional building. Its cuboid block was based on Talmudic prescriptions: It had to be taller than residential buildings. Regulations dictating that there be no decorations on the outside are connected with Roman Catholic church prohibitions. Jews lived in a Christian environment, which was governed by its own laws. Thus, ancient synagogues in our lands did not have lavish decorations. However, the community tried in some way to embellish their temples.

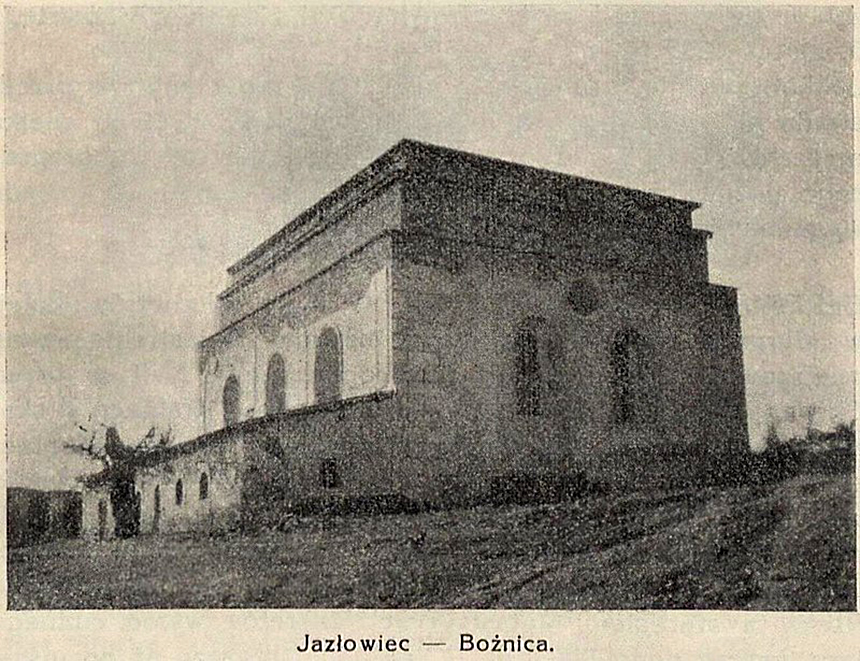

Decorations were often found in the form of a stone portal of an entry gate, which might feature beautiful Renaissance carvings. Such a portal is seen, for example, in the small synagogue in Yazlovets. Above the entry, there would frequently be a carved inscription, a quotation from the Psalms: "This is the gate of the Lord; the righteous shall enter through it." Until recently, this very inscription was displayed above the entrance to the synagogue in Pidhaitsi. Unfortunately, someone stole it. This Hebrew inscription was carved in stone.

Vasyl Shandro: But basically, it is still a cube?

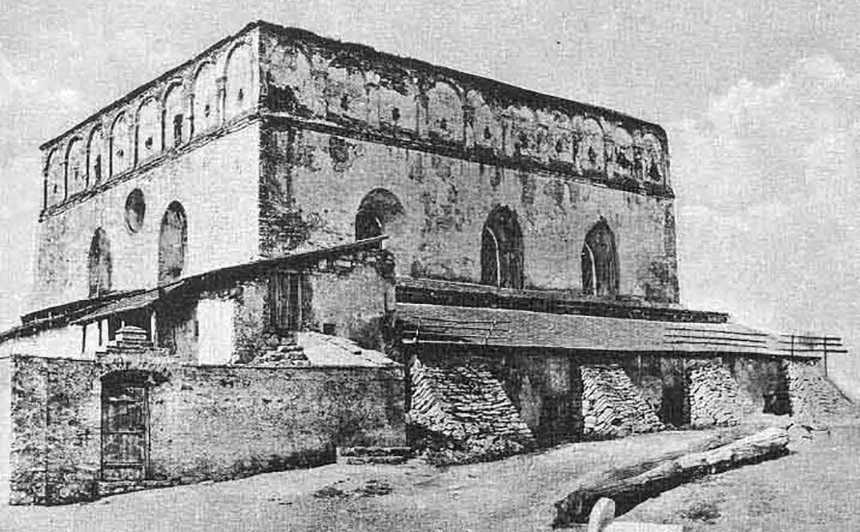

Oksana Boiko: A cube, the planes of which were enlivened only by windows and an entrance. In some synagogues, this cube was crowned by a decorated attic that became a specific feature of synagogues. But not all ancient synagogues had attics.

Vasyl Shandro: What is an attic?

Oksana Boiko: Аn attic is a short wall with a "crown" above the crown cornice on top of a synagogue. This wall closes the roof. The synagogue in Lutsk has this short wall. But it is not just a short wall. In ancient synagogues, an attic had arrow slits; it was a defensive element with a chemin de ronde [also called an allure or wall-walk: a raised, protected walkway behind a castle battlement — Trans.]. The recently restored synagogue in Sataniv also has a defensive attic, аs do the eighteenth-century synagogues in Brody and Sokal. Most synagogues were crowned with attics later, during the nineteenth century, in the process of construction or even reconstruction. An attic became a feature of synagogues because the community wanted to stand out somehow. For example, in the mid-nineteenth century, the synagogue in Belz was crowned with an attic. The cuboid blocks of ancient synagogues were surrounded by low parterre buildings, where women's prayer rooms were located.

It is very interesting that in synagogues, men and women prayed separately. Their paths did not even cross because they had separate entrances. There were separate entrances to women's prayer rooms, which were connected to the men's prayer room by small windows. The small windows were placed high up because women did not have the right to observe the service; they could only listen to it.

Over time, women's prayer rooms began to be constructed above the entrance, built onto the front, on the western side. Obviously, the construction of another women's gallery was linked to the growth of the community. It was also connected to the men's hall by small windows cut into the wall. Such windows in the western wall can be seen, for example, in the ancient synagogue in Zhovkva. Over time, this isolation disappeared, and the women's gallery was separated by screens, like, for example, in the Drohobych synagogue.

So yes, the synagogue was an ascetic cube, but over time it was transformed.

It is very interesting that in synagogues, men and women prayed separately. They did not even cross paths; they were supposed to have separate entrances.

The synagogue as a fortress against invaders

Vasyl Shandro: Can we speak of the functionality of the synagogue? We know that churches were often fortresses because they were built out of stone. That is why we can see these small windows — arrow slits — high walls, etc. In other words, when a city found itself in a difficult situation, a church could provide protection and refuge. Are we talking about synagogues in the context of defensive architecture? Did they exist in Ukraine?

Oksana Boiko: Interesting question. When you look back in time and see how everything unfolded, you cannot say that only synagogues or only churches were defensive structures. We must remember that in olden times when there was a risk of various attacks, masonry synagogues, Ukrainian churches, and Roman Catholic churches were built as defensive structures. All of them had very thick walls, up to two meters. They had clerestory windows and a very solid gate, so that the enemy could not enter. I talked about attics, which not all synagogues had. Incidentally, the document granting permission to build the Lutsk or Sataniv synagogue stated that an attic was required so that the community could have a chance to protect itself from an enemy. For that reason, the attics in these synagogues were defensive from the outset, and they featured a chemin de ronde and arrow slits, through which you could shoot back.

Over time, attics, which no longer had a defensive function, became an architectural feature of synagogues. For example, the synagogue in Zhovkva, which has a non-defensive attic, has arrow slits. But if you go onto the roof, you can see that it is not adapted for defense because the chemin de ronde is too high. An attic can also be too low. In that case, the attic is merely a decorative element, a feature of a synagogue. But all ancient sacred buildings — both [Ukrainian] and Roman Catholic churches — were defensive, for example, in Pidhaitsi, where there were thick walls and exits to the roof, to that attic.

Vasyl Shandro: In other words, can we say that, in keeping with urban planning, these buildings were supposed to be situated in a certain way, so as to create a defensive ensemble? Or am I overstating things?

Oksana Boiko: That's about the size of it. It derived from the principles of defending a city, because ancient cities had fortifications. These fortifications were not all that strong. They were earthen ramparts with water-filled moats. The earthen ramparts had a defensive wall, usually built out of timber; that is, they were half-timbered, with a wooden frame filled with clay. The city had gates that were locked at night.

As a rule, there were two gates in small towns, sometimes even three, if there were more roads leading to and out of them. Lviv had two main gates: Krakivska and Halytska, as well as two wickets: Yezuitska and Bosatska. All sacred masonry buildings that were inside the city were also defensive, of course. This type of construction continued until the mid-eighteenth century, when the need for defense disappeared. The temples of various communities, which were built in the mid-eighteenth century (synagogues, [Ukrainian] churches, and Roman Catholic churches), no longer required thick walls. But baroque synagogues dating to the mid-eighteenth century — particularly in Brody, Sambir, Sokal, or Husiatyn — were still built with thick walls.

Ukrainian cultural influences on synagogue decorations

Vasyl Shandro: Can one speak of certain influences or mutual influences with regard to decorations? Can we see typical Ukrainian ornamentation on synagogues, for example, somewhere in the Carpathians, given that master craftsmen could be locals who were familiar with local traditions and patterns that they sculpted onto buildings, regardless of religious affiliation? Or was the visual aesthetic concept still very strictly maintained?

Oksana Boiko: If we are talking about similar influences and mutual influences, then this pertained for the most part to wooden synagogues, because the nature of the architectural and construction solution regarding wooden synagogues was formed under the influence of local methods of log construction. We know that churches were built with logs; even residences were built of logs. To a great extent, this log construction was combined with roofs with rafters.

Similar to churches, synagogues had a coronal construction blended with Ukrainian forms of timber frames featuring folding, hanging rafters, which are typical of the Western European type of construction.

The influence of traditional local building on wooden synagogues has been discussed by many scholars who have studied this type of construction. For example, the architect and theoretician Adolf Shyshko-Bohush commented that Jewish culture was not strong enough to create its own architecture. But wooden synagogues — this is our architecture; what is Jewish about them was that which derived from ritualistic requirements. Furthermore, if we recall the most characteristic wooden synagogues, like the ones in Khodoriv, Hvizdka, and Yabluniv, these were immense cuboid blocks covered with grooved roofs. They were somewhat similar to churches, but they were much wider.

The destruction of synagogues in wartime and during the postwar period

Vasyl Shandro: I propose to devote the time remaining on our show to your monument-conservation activities. To a great extent, they pertain to synagogues as well. The twentieth century was a terrible period for architecture in general and sacred architecture in particular: not just synagogues, but also Roman Catholic churches, and Ukrainian churches — everything that pertained to religion.

What happened to synagogues? Did they suffer the same fate as churches: repurposed into museums and warehouses; ruination; stripped of their bricks and stones; their transformation into functional buildings? What happened in western Ukraine after the Second World War?

Oksana Boiko: Here, we have to start with the First World War. The wars of the twentieth century brought terrible devastation to Galicia. We do not even comprehend what happened during the First World War. Immense numbers of innocent people were killed, and all small towns were totally destroyed. Today, thanks to the Internet, there is access to various materials. We can see many photographs from that period, which show these ruins. Practically all our small towns had been destroyed, and they were rebuilt during the interwar period. Since synagogues were mostly wooden and every small town had one, practically all of them burned down during the First World War. Those that remained standing — and there were only a few of them — burned down during the Second World War. What happened to the synagogues that had survived the First World War? For the most part, only masonry buildings remained intact. In Lviv, the Nazis destroyed all the iconic ancient synagogues. The Great Suburban Synagogue, the Great City Synagogue, and the Tempel Synagogue of Reform Judaism were all blown up. Unfortunately, the preserved ruins were dismantled during the postwar years. The oldest synagogue, the Golden Rose, was preserved in the form of ruins. The buildings that remained intact were repurposed. Of course, the synagogue interiors were looted, and only bare walls were left, often without a roof. At best, stucco work and murals remained.

How were the intact structures repurposed? They became gymnasiums, clubs, movie theaters, and residential buildings. In any case, this was a good thing because they were no longer subject to destruction, even if a synagogue was turned into a warehouse that needed a roof.

What happened to the churches? The situation with all sacred buildings was dismal, including churches that were also destroyed during the Soviet period. Liturgies were banned, and the buildings stood unused, and occasionally were turned into some type of warehouse. A grim fate also befell Roman Catholic churches. In 1946 practically all the Poles had left, and their churches stood empty. They, too, were repurposed in a variety of ways. This was a terrible disaster. Of course, those churches that reverted to Orthodoxy continued to function. This was good because they were preserved.

During the Soviet period, the institute where I work was engaged in researching and recording the architectural heritage of western Ukraine. Project documentation on the restoration of various monuments, including synagogues, was developed. Of course, few of them were restored, but at least they were recorded.

We never thought that during the period of independence, such crucial institutions as the Ukrzakhidproiektrestavratsiia, which dealt with culture and monuments, would be ravaged.

We recorded many monuments and developed numerous restoration projects. We restored numerous wooded churches, and Roman Catholic churches and synagogues were converted. At least some attempts were made.

By contrast, during the post-independence period, when monuments should have been preserved, even those institutions that had functioned successfully during the Soviet period were ravaged.

Culture does not start from a clean sheet. Culture exists, and it requires engagement. Institutes that have dealt with the preservation of the cultural heritage must not be destroyed; they must be strengthened and reformatted. Today we have a great lack of architects and restorers. The government announced the "Great Restoration," but there is no one to draw up restoration documentation because the appropriate institutions have been wrecked. In our country, continuity has been interrupted. There is a Department of Restoration at the Lviv Polytechnic, but graduates have nowhere to do their practical work and gain experience. That is why they are vanishing.

Returning to the synagogues that remain, I must say that they have experienced a variety of fates. Of course, something good is being done. For example, conservation work has been done on the Golden Rose Synagogue in Lviv. The synagogue in Sataniv has been restored. On the one hand, this is good. But the way its original appearance has been preserved is a disgrace. It resembles a business project into which huge amounts of money have been sunk. Marble and other expensive materials have been shoved into this synagogue, and it glitters all over. The work was done very improperly. This ancient defensive temple has been turned into a "Eurosynagogue."

Skilled restoration work, supervised by Hryhorii Arshynov, was done on the synagogue in Ostroh. Unfortunately, he died of COVID. That is a great shame. He had so much energy and aspirations. His actions were good, and he did everything correctly. We lack such people.

Vasyl Shandro: Are there still some synagogues that are not being used according to their designated purpose?

Oksana Boiko: Of course, such synagogues comprise the majority because there are no Jewish communities. If there is no community, then the synagogue does not fulfill its function. A few years ago, the synagogue in Drohobych was restored with funds supplied by a native of that city who lives in Moscow; he is a wealthy individual — perhaps even an oligarch. He invested a large amount of capital into restoring this huge synagogue. Today it is used for a variety of gatherings. Of course, Jews who gather from all over the world hold services there. Perhaps they pray in some smaller venue. But the main prayer hall is used for concerts, exhibitions, and various cultural events, and this is correct.

I think that if the state wanted to look after this immense stratum of synagogue architecture, this would be fascinating work for specialists. Today natives of small towns and their descendants are visiting their birthplaces. They visit iconic locations, cemeteries, which are mostly untended. They visit synagogues, if they have been preserved. One often feels shame for their neglected state. That is why great attention must be devoted to the preservation of synagogues.

This program is created with the support of Ukrainian Jewish Encounter (UJE), a Canadian charitable non-profit organization.

Originally appeared in Ukrainian (Hromadske Radio podcast) here.

Translated from the Ukrainian by Marta D. Olynyk.

Edited by Peter Bejger.

NOTE: UJE does not necessarily endorse opinions expressed in articles and other materials published on its website and social media pages. Such materials are posted to promote discussion related to Ukrainian-Jewish interactions and relations. The website and social media pages will be places of information that reflect varied viewpoints.