"The Russians came not only with rocket launchers but with victory banners, mobile eternal flames, and honor guard uniforms": Mischa Gabowitsch and Mykola Homanyuk on Russia's commemorative invasion of Ukraine

Ukrainian sociologist Mykola Homanyuk and German historian and sociologist Mischa Gabowitsch discuss their recently published book, Monuments and Territory: War Memorials in Russian-Occupied Ukraine. They examine the strategies behind Russia's commemorative policies in the Ukrainian territories it occupied between 2022 and early 2023, reflect on Ukraine's own approaches to memory and decolonization, and explore the differing memorial practices in urban versus rural communities.

"In Russia, both government agencies and individual sculptors are invested in symbolically colonizing the occupied territories."

You recently published Monuments and Territory: War Memorials in Russian-Occupied Ukraine. What sparked the idea for this book?

Mykola Homanyuk: From the first days of the full-scale invasion, it was clear that Russian forces were placing exceptional emphasis on war memorials in the territories they seized. This wasn't some ad-hoc improvisation — although there was certainly some of that too. We felt it was crucial to document what are essentially internal directives and practices — materials that historians or legal scholars might not have access to for a long time, if ever. These are documents and actions that show how Russia intended to manage memory in the occupied territories. Because let's be honest — the Russians didn't just come with Grad and Solntsepyok rocket launchers. They also brought WWII victory banners, mobile eternal flames, and full ceremonial uniforms for honor guards. Memorials became stages for a different kind of weaponry — symbolic, but no less aggressive.

Mischa Gabowitsch: At first, we thought this would be just an article. But as we started collecting material and writing, it soon became clear that the result would be a book. For one thing, there was just so much of it — the Russians engaged with memorials in dozens, maybe hundreds, of towns and villages, and they documented it all through photos and videos shared in Telegram channels. For another, the subject turned out to be far more complex than we expected. We found ourselves exploring everything from how this compares with other cases of what we call "imperial irredentism," to how Russian occupiers reacted to grassroots ways of engaging with monuments in Ukrainian villages, to how they used memorial imagery in propaganda campaigns — and much more.

What kinds of commemorative policies has Russia implemented in the occupied Ukrainian territories? Do you see these as long-term trends?

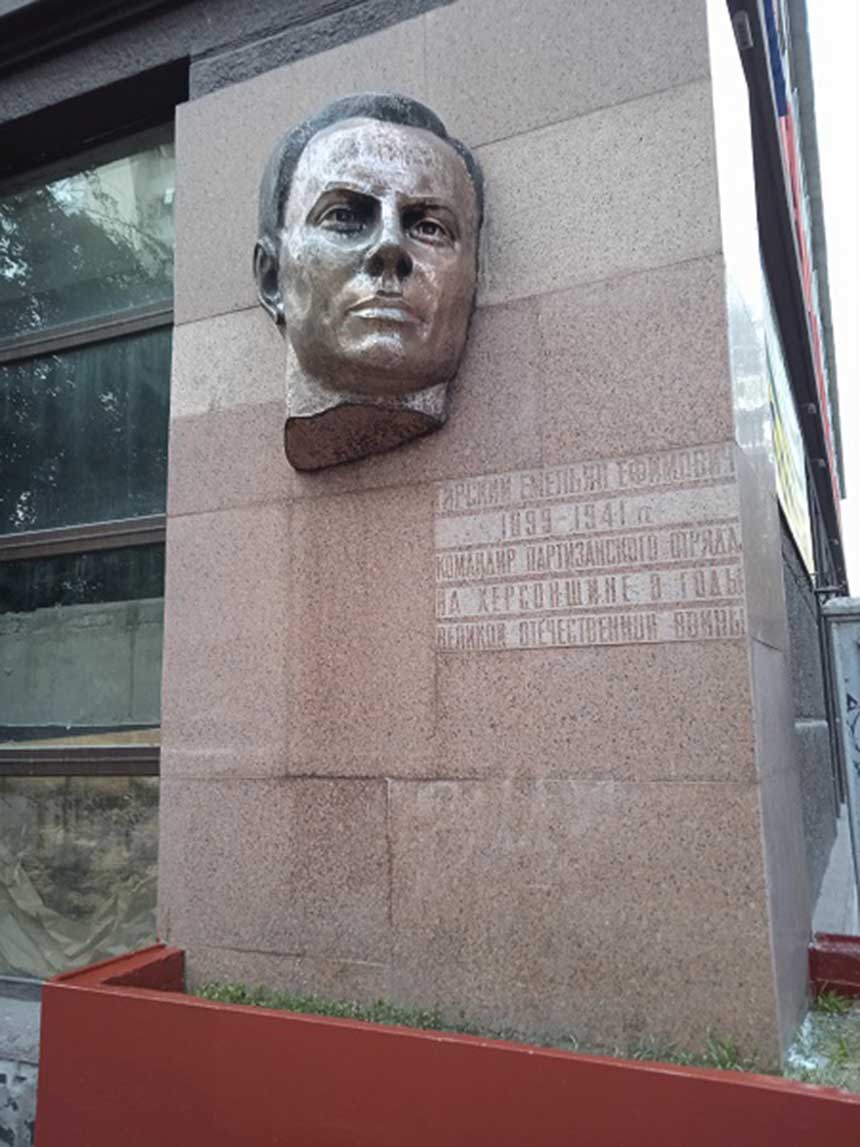

Mykola Homanyuk: Our research focused on the first year of the full-scale invasion, starting from February 24, 2022. Even after the one-year mark, many of the practices we observed continued. For instance, we saw a wave of iconoclasm targeting memorials to the victims of the Holodomor. The return of Lenin monuments — what Julie Deschepper calls the opposite of "Leninfall" — also persisted, although mainly in rural areas. Even monuments to Taras Shevchenko weren't immune: they were selectively restored and even "museumified" within the broader context of Russia's so-called Special Military Operation.

Mischa Gabowitsch: And that's just part of the picture. In addition to restoring Soviet-era monuments, the Russians also installed entirely new ones in the occupied territories: a bust of Pavel Sudoplatov, the polymer statue Granny with a Red Flag, an equestrian monument to Alexander Nevsky, and several others. These were all in regions taken after February 2022. But the invasion also accelerated the completion of projects that had been stalled since 2014 — like the memorial at Savur-Mohyla. What's more, Russia isn't doing this only through state institutions. There are also individual sculptors and architects involved in what you could call the symbolic colonization of space. One telling example is the "Russia – My History" multimedia parks opened in Luhansk and Melitopol. Another is the architectural project Beacons of the Russian World, which recasts parts of Ukraine as "Novorossiya" — New Russia.

Have these memorializing and commemorative practices had any impact on how local Ukrainians view the Russian occupation?

Mykola Homanyuk: I'd say — no, not really. The Russians came claiming to protect monuments to the Great Patriotic War. But what they found were already well-maintained Soviet-era monuments, along with newer World War II memorials built during Ukraine's independence. In other words, they weren't offering anything new or needed. Because of that, when they tried to organize large-scale commemorative events, they often had to bus in people from Crimea or the so-called ORDLO (the temporarily occupied areas of Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts) to create an illusion of public support.

Mischa Gabowitsch: What's even more interesting is the reverse effect — how local traditions influenced the occupiers. This continues a long-standing Soviet pattern: local forms of remembrance would often be adopted into the broader official canon. Think of things like lighting an eternal flame or organizing meetings with war veterans — many of those started at the grassroots level. In 2022, we saw something similar with polychromy — the practice of painting monuments in multiple bright colors, which is common in rural Ukraine but rare elsewhere in the post-Soviet space. Initially, Russian occupiers saw this as a kind of sacrilege. But eventually, they started repainting and polishing even bronze statues — essentially co-opting this visual style as their own.

"Ukrainian ancestors aren't divine or infallible. They're human — and they seem to reach out and shake your hand from across time, not rule over you from above."

What trends have emerged in Ukraine's own memorialization practices since February 24, 2022?

Mykola Homanyuk: First, there's been a widespread effort to commemorate the current war — through monuments, museum exhibitions, and renaming streets and places. Second, we're seeing a kind of hybridization of memorials: new ones aren't replacing the old but being added alongside them, sometimes even becoming part of existing compositions. Third, the style of commemoration combines two distinct aesthetics. On one hand, you have hyperrealistic portrayals of fallen soldiers — incredibly detailed, lifelike depictions. On the other hand, memorials often follow the conventions of traditional Ukrainian family gravestones, especially the use of polished granite. As for Soviet-era monuments, the iconoclastic wave against them has been uneven. It's only in Lviv oblast that the process has been consistent and systematic.

Mischa Gabowitsch: There's another development worth highlighting. At the very end of the Soviet era, new groups — like veterans of the Soviet war in Afghanistan, Chernobyl liquidators, or border guards — began to get their own monuments, usually placed next to existing WWII memorials. The new monuments derived their legitimacy from being physically close to the old ones. In today's Ukraine, we're seeing that logic flipped on its head. Now it's the WWII memorials that are being preserved or re-legitimized by having elements of the current war — names, portraits of soldiers — added to them.

Mykola Homanyuk: It's as if the old Soviet memorials are drawing credibility and emotional power from their association with new ones.

You've written that Ukrainian media tend to depict monuments in a more democratic, less hierarchical way. In contrast, Russian outlets favor low-angle shots that elevate WWII heroes to almost divine status. What does this say about how each country relates to the memory of the war?

Mischa Gabowitsch: In Russia, Red Army soldiers are presented as larger-than-life figures — practically mythical. The message is clear: "Be worthy of your great forefathers." That reverence becomes politically powerful, especially in a country where any critical discussion of WWII is off-limits. The state controls the narrative, and that narrative can be used to justify anything — including military aggression. Of course, Ukraine also engages in hero-making, and even supporters of Stepan Bandera or the UPA sometimes use Soviet-style language to talk about their heroes. But visually, the tone is very different. Ukrainian memorials also tend to emphasize a sense of continuity — "Our grandparents fought the fascists, now it's our turn." But it's more horizontal, more egalitarian. Ukrainian ancestors aren't divine or infallible. They're human — and they seem to reach out and shake your hand from across time, not rule over you from above.

Mykola Homanyuk: And importantly, this democratization of Soviet memorials started well before 2022. In many places, WWII monuments were reinterpreted and integrated into Ukraine's national commemorative landscape from the ground up — organically, not by government decree. We devote an entire chapter of the book to this process.

In your book, you note that the dismantling of Soviet WWII monuments is spreading beyond Ukraine. How is this playing out in other Eastern European countries? And how have people in Western Europe — including policymakers in Germany or France — reacted?

Mischa Gabowitsch: Media headlines often claim that, in response to Russia's invasion, Soviet war memorials are being torn down "across Europe." But that's an exaggeration. Systematic removal has only happened in four countries: Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, and Poland. In Ukraine itself, dismantling has been more localized — mostly in Lviv oblast and, to some extent, in the Ivano-Frankivsk and Ternopil regions. In other parts of the country, some monuments have been taken down or destroyed, but there's no centralized, nationwide effort. After February 2022, Czechia and Bulgaria each dismantled one or two monuments, but elsewhere — from Norway to Italy — most memorials to Red Army soldiers are still standing. At most, they might be vandalized with anti-Russian graffiti or decorated with Ukrainian symbols, like we've seen in Germany and Austria. What's more, some countries — not just Russia and Belarus, but also Hungary, Serbia, and Bosnia-Herzegovina — have even unveiled new monuments to the Red Army since the invasion.

Mykola Homanyuk: And don't forget the South Caucasus. In 2024, after Azerbaijani forces captured Nagorno-Karabakh, several Soviet war memorials disappeared from public view. Among them were monuments to Marshal Ivan Bagramyan and Admiral Ivan Isakov. That probably had less to do with their wartime roles and more with the fact that they were ethnically Armenian.

"Memory in cities is more impersonal"

Some Ukrainian experts worry that dismantling Soviet WWII monuments allows Russia to monopolize the victory narrative. Others argue that defeating Nazism is itself a core value that deserves recognition, regardless of what Russia does. Still others insist Ukraine should purge all Soviet symbols, period. What's your stance?

Mykola Homanyuk: We lay out our position clearly in the book's conclusion. A monument is never just one thing. It's a political statement, yes — but it's also a historical artifact, an artistic object, a physical feature of the local landscape, and often a part of people's daily lives. That's why I'd argue against all-or-nothing thinking. Instead of framing everything in binary terms — keep it or destroy it — we should approach monuments as multi-dimensional objects.

Mischa Gabowitsch: Exactly. Every monument has its own "biography" — a backstory that includes the debates and decisions that led to its creation. Scholars like James E. Young, who specializes in Holocaust memorials, argue that these discussions are often more important than the monuments themselves. The same goes for dismantling or reinterpreting monuments: the process matters. Sweeping changes without public debate — just clearing the slate — that's a very Soviet way of handling public space. What I find more constructive are counter-monuments — additions that challenge or recontextualize an existing monument without erasing it. These kinds of interventions, already tested in many countries, offer more educational value than simply tearing things down. And when removal is necessary, it should come after a thorough and democratic conversation.

You note that people in rural Ukraine — even in the western oblasts — are more likely to preserve Soviet-era monuments to the victory over Nazism than urban residents. Why is that? Can cities learn something from villages?

Mykola Homanyuk: In cities, commemoration tends to be more anonymous. For example, you rarely find memorial stelae listing all the local residents who died in WWII. In villages, that's the norm. Even those who died defending or liberating the village are often listed by name. Families visit these sites, find their relatives' names, and sometimes add portraits or additional details over time. Doing something like that in a city would be much harder — it would probably draw attention from the authorities immediately. In the countryside, though, these monuments were gradually de-communized and decolonized from the bottom up, without any official directives. Today, we're seeing that same approach begin to spread to larger urban centers.

Mischa Gabowitsch: There's a common assumption that commemoration starts in big cities and then filters down to smaller towns. In reality, the opposite often happens. In the USSR, the very first WWII monuments appeared in rural areas near actual battlefields. During that same period, it was almost impossible to erect Holocaust memorials in big cities — but hundreds were built in small towns and villages. Аrkadi Zeltser writes about this in detail. Yuliya Yurchuk's research shows the same thing happening after Ukraine became independent: monuments to the OUN and UPA often appeared in villages first — sometimes right next to Soviet memorials that had previously condemned the UPA. And the same people would bring flowers to both. In big cities, conversations about public space tend to get trapped in ideological debates. But in smaller communities, monuments have multiple meanings. They're not just political symbols — they're family markers, local landmarks, and part of the everyday landscape. And that makes the memory they represent feel more personal, more rooted.

"I can't recall a single instance where Russian occupiers commemorated Holocaust victims in Ukraine."

Soviet war memorials sometimes referenced the Holocaust, though often vaguely and without explicitly identifying Jewish victims. In your research, have you found any clear positions — from either Russian or Ukrainian authorities — on Soviet-era Holocaust memorials?

Mykola Homanyuk: We mention Holocaust-related memorials like Babyn Yar and Drobytsky Yar in the context of their partial destruction during Russian shelling. Those incidents got a lot of media coverage in Ukraine and were used to highlight the horror and symbolic violence of the invasion. But when it comes to the occupied territories, the Russians largely ignored Holocaust sites. In our book, we included a calendar of commemorative dates officially marked in those territories under Russian control. It's filled with all kinds of events — even ones with no connection to Ukraine, like the anniversary of the Beslan school siege or the lifting of the siege of Leningrad. But not once — not a single time — do we see any recognition of Holocaust victims. That's a stark example of Russia's selective memory when it comes to WWII history.

Mischa Gabowitsch: This selective memory is part of a broader pattern across the post-Soviet space — not just in Russia or Ukraine, but in most former Soviet republics. Even though there have been important local initiatives, the Holocaust — and especially the genocide of Roma and other groups — has never become a central part of public historical awareness. After 1991, many of the grassroots Holocaust memorials that had been erected during the Soviet era were replaced by new ones with a more "international" aesthetic. But even those didn't really enter public consciousness. They've often been placed apart from the main WWII monuments, treated like footnotes rather than focal points. That's probably why they've been of little interest to the Russian occupiers. They don't fit the narrative.

At the beginning of the full-scale invasion, both Ukrainian and Russian media frequently compared today's war to WWII, Nazism, and the Holocaust. How have those comparisons evolved? Are they intentional, or do they just emerge from the lasting cultural imprint of the Second World War?

Mykola Homanyuk: It really depends on the time period. In 2022 and the first half of 2023, there was a surge in comparisons between Russia and Nazi Germany. Ukrainian soldiers were likened to UPA fighters or even to Red Army soldiers. But over time, those comparisons started to fade. The rhetoric cooled a bit — perhaps because the public and the media were becoming more focused on the present realities of the war rather than historical analogies.

Mischa Gabowitsch: On the Russian side, there's an interesting historical twist. In Soviet tradition, the word "fascists" was typically used for ideological enemies — Germany, of course, but also Tito or even the United States. But "Nazis" had a more specific connotation. It was often used to describe groups that the Soviet Union saw as puppets of the West — like the East German protesters in 1953, the Hungarian revolutionaries in 1956, or the Prague Spring participants in 1968. Today, Ukrainians are called "Nazis" more often than "fascists" in Russian propaganda, because the Kremlin insists Ukraine isn't acting independently — it's supposedly controlled by the U.S. or "the West." So when Russian state media talks about a "Nazi junta in Kyiv," it's not just a WWII reference. It also echoes 1968 and the invasion of Czechoslovakia. Russian wartime rhetoric is messy and syncretic — it blends together everything from Alexander Nevsky to Soviet Spetsnaz mythology, using whatever suits the moment.

"Ukraine's imperial past — and its monuments — are a fundamental part of its history."

There's an ongoing debate in Ukraine about removing not only Soviet monuments, but also pre-Soviet ones tied to Russian imperialism. Some, like the Pushkin monument in Odesa, date back to before the Soviet era. How have other cities handled this?

Mykola Homanyuk: It's been different from place to place. For example, Kharkiv relocated its pre-Soviet Pushkin statue to a museum. Some tried reframing these monuments instead of removing them — in Kharkiv's case, by highlighting the story of activists from the early 20th-century independence movement who once tried to blow up the statue. In Kherson, the Russians actually looted the monument to Potemkin — a copy of the original sculpture by Ivan Martos — which effectively ended any debate about its fate. Some monuments, like the Suvorov statue in Ochakiv, are still standing, even though the street it's on has been renamed. Others — like the ones in Izmail and Tulchyn — have been taken down. What's especially interesting is that Ukraine also has monuments to figures from other empires, like the Habsburgs — and nobody seems to mind. There are statues of Franz Joseph in Chernivtsi and Maria Theresia in Uzhhorod, both installed in the 2000s. These haven't become flashpoints for decolonization debates, even though they easily could be.

In Ukraine, terms like decolonization, de-imperialization, and decommunization are often used to describe these changes in the memorial landscape. How would you define these processes — and what principles should guide them?

Mykola Homanyuk: One qualifier needs to be added to each of those terms, and that's "selective." Ukraine — and Ukrainians — have been both colonizers and colonized, depending on the historical moment. Take de-imperialization. It's often applied to Russian or Soviet legacies, but almost never to the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Why not? The same goes for decommunization — we're very focused on removing Lenin, but figures like Dovzhenko, Tychyna, or Honchar don't attract much attention from activists. Personally, I'm not a historian. I'd like to see these decisions preceded by open discussion so we can all make sense of them. That said, I've spent a lot of time trying to foster local self-government, and I believe it's one of Ukraine's greatest strengths. Communities — not just the state — should have more autonomy in shaping how they commemorate their past. And we shouldn't forget that the so-called "silent majority" often has an opinion too — even if it's not expressed through activism.

Mischa Gabowitsch: I think it's important to remember that none of these "de-" processes will return Ukraine to some primordial pre-imperial condition. Ukraine's time under various empires — and the monuments that came from that — is an integral part of the country's history. Sometimes, it makes sense to move monuments into museums. But sometimes, it might be more valuable to leave them in place and reinterpret them — to use them as tools for critical engagement with the past. As Mykola said, these decisions should be made locally. What matters is that they happen through thoughtful, democratic conversation — not through top-down decrees.

Interviewed by Petro Dolhanov.

The photographs featured in this text are from the private collection of Mykola Homanyuk.

Mischa Gabowitsch is Professor of Multilingual and Transnational Post-Soviet Studies at Johannes Gutenberg University of Mainz in Germany, and the author or editor of the following books: Pamiat′ o voine 60 let spustia: Rossiia, Germaniia, Evropa [The Memory of the War 60 Years Later: Russia, Germany, Europe] (2005); Putin kaputt!? Russlands neue Protestkultur [Russia’s New Culture of Protest] (2013); Protest in Putin’s Russia (2016); Replicating Atonement: Foreign Models in the Commemoration of Atrocities (2017); Kriegsgedenken als Event. Der 9. Mai 2015 im postsozialistischen Europa [War Commemoration as an Event: May 9, 2015, in Post-Socialist Europe] (co-edited with Cordula Gdaniec and Ekaterina Makhotina, 2017); Pamiatnik i prazdnik: Etnografiia Dnia Pobedy [Monument and Holiday: An Ethnography of Victory Day] (2020); Monuments and Territory: War Memorials in Russian-Occupied Ukraine (co-authored with Mykola Homanyuk, 2025).

Mischa Gabowitsch is Professor of Multilingual and Transnational Post-Soviet Studies at Johannes Gutenberg University of Mainz in Germany, and the author or editor of the following books: Pamiat′ o voine 60 let spustia: Rossiia, Germaniia, Evropa [The Memory of the War 60 Years Later: Russia, Germany, Europe] (2005); Putin kaputt!? Russlands neue Protestkultur [Russia’s New Culture of Protest] (2013); Protest in Putin’s Russia (2016); Replicating Atonement: Foreign Models in the Commemoration of Atrocities (2017); Kriegsgedenken als Event. Der 9. Mai 2015 im postsozialistischen Europa [War Commemoration as an Event: May 9, 2015, in Post-Socialist Europe] (co-edited with Cordula Gdaniec and Ekaterina Makhotina, 2017); Pamiatnik i prazdnik: Etnografiia Dnia Pobedy [Monument and Holiday: An Ethnography of Victory Day] (2020); Monuments and Territory: War Memorials in Russian-Occupied Ukraine (co-authored with Mykola Homanyuk, 2025).

Mykola Homanyuk is Associate Professor in the Department of Geography and Ecology at Kherson State University. He is the author or publisher of the following books: Interv'iuer u masovomu opytuvanni [The Interviewer in Mass Surveys], (2013); Atlas etnichnykh hrup Khersons′koї oblasti [Atlas of Ethnic Groups in Kherson Oblast], (2016); Etnichnist′ u ZMI: Porady zhurnalistam [Ethnicity in the Mass Media: Advice to Journalists], (2017); Odushevleni predmety [Animate Objects] (2020); Radymos′ z hromadoiu: Orhanizatsiia konsul′tatsii z hromads′kistiu v terrytorial′nii hromadi [Consulting with the Community: Organizing Public Consultations within Territorial Communities] (2023); Monuments and Territory: War Memorials in Russian-Occupied Ukraine (co-authored with Mischa Gabowitsch, 2025); Zvil′nena karta: Dovidnyk novykh heonimiv Khersons′koї hromady [The Liberated Map: A Guide to New Geonyms of the Kherson Community] (co-authored with Dementiy Bilyi, 2025).

Mykola Homanyuk is Associate Professor in the Department of Geography and Ecology at Kherson State University. He is the author or publisher of the following books: Interv'iuer u masovomu opytuvanni [The Interviewer in Mass Surveys], (2013); Atlas etnichnykh hrup Khersons′koї oblasti [Atlas of Ethnic Groups in Kherson Oblast], (2016); Etnichnist′ u ZMI: Porady zhurnalistam [Ethnicity in the Mass Media: Advice to Journalists], (2017); Odushevleni predmety [Animate Objects] (2020); Radymos′ z hromadoiu: Orhanizatsiia konsul′tatsii z hromads′kistiu v terrytorial′nii hromadi [Consulting with the Community: Organizing Public Consultations within Territorial Communities] (2023); Monuments and Territory: War Memorials in Russian-Occupied Ukraine (co-authored with Mischa Gabowitsch, 2025); Zvil′nena karta: Dovidnyk novykh heonimiv Khersons′koї hromady [The Liberated Map: A Guide to New Geonyms of the Kherson Community] (co-authored with Dementiy Bilyi, 2025).

Originally published in Ukrainian @Ukraina Moderna

This article was published as part of a project supported by the Canadian non-profit charitable organization Ukrainian Jewish Encounter.

Translated from the Ukrainian by Marta D. Olynyk

NOTE: UJE does not necessarily endorse opinions expressed in articles and other materials published on its website and social media pages. Such materials are posted to promote discussion related to Ukrainian-Jewish interactions and relations. The website and social media pages will be places of information that reflect varied viewpoints.