The Ukrainian Auxiliary Police in Kyiv and Adjacent Areas, pt. 1: Formation and Activities

[Abstract: This research article by the Ukrainian historian Daniil Sytnyk examines the particularities of the formation and activity of the auxiliary police in Nazi-occupied Ukraine. The author highlights the specifics of the creation of police units in the city of Kyiv and its vicinities. In focusing on this area, he draws conclusions about the main features of recruitment, paints a collective portrait, and outlines the motivation and role that policemen played during the Nazi occupation. The historian devotes separate attention to the evolution of the institutional structure and management of the auxiliary police throughout the Nazi occupation.]

By Daniil Sytnyk

Was there a unique form of collaborationism that was exclusively Ukrainian (or any other nationality) during the Second World War? We know from scholarly literature and various sources that the newly created Ukrainian Auxiliary Police (hereafter cited as UAP), just like the Polish, Belarusian, and Russian versions, had an identical range of duties and were regularly involved in acts of mass violence. For example, the members of a Belarusian auxiliary police battalion took part in the shootings of nearly 800 Jews in the Koldychevo camp; the Russian auxiliary police deported and killed 2,000 Jews from the Smolensk ghetto in July 1942; and the 12th Lithuanian Police Battalion was involved in the October 1941 murders of 5,900 Jews on the Slutsk-Kletsk (Belarus) line. The numerical strength of, say, the Polish police in Warsaw alone was nearly two times greater (3,100) than the number of UAP members in Kyiv during the same period. [1] Then why does the topic of the latter's crimes appear in the information space and academia more frequently than other similar cases? In my view, the answer is twofold. First, the topic is better researched academically (as a result of the ease of access to archives, freedom of discussion, and the existence of a generation of researchers studying the Holocaust in Ukraine). Second, targeted instrumentalization of historical memory for political reasons is taking place. For example, Russian propaganda equates the Ukrainian liberation movement with the Nazis.

Unlike propaganda, scholarly work does not have any political tasks; its goal is not to form a negative image in the contemporary world by researching the past. Thus, before reading the main text, readers should keep in mind that no propaganda activity should cast doubt on scholarly work. No matter what the pages of the past reveal, they are worth researching and being discussed.

Preconditions

The attack on the Soviet Union by the combined armies of Germany and its allies on 22 June 1941 was the turning point in the development of many European nationalist movements. Besides the Ukrainian one (for example, the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists), Baltic (Lietuvos Aktyvistų Frontas), Belarusian (Belaruskaia nezalezhnitskaia partyia), and Russian (Natsionalno-trudovoi soiuz novogo pokoleniia), many other right-wing organizations viewed this war as a "crusade against Bolshevism." [2] However, this "campaign" was not an end in itself but signaled the liberation of those territories to be followed by the establishment of independent national states. In the conditions of total war, having one's own armed forces was crucial for this aim. During the first year of the war, the Germans did not allow any of the nationalities mentioned above to create them. However, they did not object to the formation of a network of disparate paramilitary units that were ultimately transformed into auxiliary police forces. Let us take a closer look at the Ukrainian scenario.

The idea to create paramilitary units that were later transformed into the UAP can be traced back to the interwar period. Above all, they were the product of German-Ukrainian contacts on various levels. The OUN saw material benefit in cooperating with Germany and the possibility of realizing its main goal: the restoration of Ukrainian statehood. Depending on external political circumstances, these contacts were severed and then restored throughout the 1930s. However, even the pragmatic nature of German-Ukrainian cooperation receded when discussions shifted to the issue of political concessions and guarantees. The highest leadership of the Third Reich was not about to help the Ukrainians achieve independence, let alone willingly hand over Soviet Ukrainian territories that they would capture after bloody battles.

Thus, shortly before the beginning of the Second World War, the Germans gave the green light to creating so-called Military Units of Nationalists (VVN). One such small volunteer unit was headed by Roman Sushko, a member of the OUN's highest leadership and a former colonel of the UNR Army. When Germany attacked Poland, the VVN's activity was strictly limited to pure policing, according to the terms of the German-Soviet Non-Aggression Pact signed in August 1939. When the Polish campaign ended, the personnel of Sushko's unit were divided up among a few cities in the newly created Generalgouvernement, where they were used to guard industrial installations (Werkschutz). As a result of the Polish campaign, Eastern Galicia, the birthplace of many Ukrainian nationalists, became part of the Soviet Union, an event that also stunned the nationalists. Ultimately, though, this did not turn them away from Germany. [3]

In December 1939, the first Ukrainian police stations (their personnel was also selected from among VVN members) were formed on the territory of the Lublin and Cracow districts. By the second half of 1940, police schools for rank-and-file policemen and officers were established in Cracow, Chełm, and other cities. Despite their presence, the Polish police were the key auxiliary force on the territory of the Generalgouvernement. Subsequently, it was only the occupation of Eastern Galicia and its inclusion as a district in this territorial unit that served as an impetus for granting permission to create a Ukrainian auxiliary police on 12 August 1941. Its members filled all the positions in the auxiliary police force in the District of Galicia. In contrast, the District's criminal police consisted almost entirely of ethnic Poles, as current research shows. [4]

Drafted shortly before the start of the German-Soviet war, instructions like the Banderite document "The Struggle and Activity of the OUN during the War" emphasized the importance of forming a so-called Ukrainian people's militia, i.e., paramilitary OUN detachments that would carry out policing functions on the ground, while also creating reserve cadres for a future Ukrainian army. According to the nationalists' thinking, only a regular army could help them succeed in realizing their main goal of creating and defending an independent Ukraine. Thus, forming paramilitary detachments was a top-priority task of OUN expeditionary groups that immediately set out with or after the German army when the German-Soviet war began.

The creation of paramilitary detachments (militias) in the occupied Ukrainian SSR

As it turned out, the members of the nationalist underground did not have sufficient cadres to cover all of Ukraine with a network of trusted people. Therefore, the process of creating paramilitary detachments in every populated area occurred in various ways. Three scenarios can be singled from among the most prevalent ones: (1) on the initiative of the local inhabitants of a populated area; (2) in keeping with an order issued by the local German command; and (3) on the direct instructions of the dominant political organization. [5]

The first two scenarios pertained mostly to populated areas on the raion level (villages, hamlets, etc.), where the question of forming police detachments was tabled at meetings of local residents. Personnel were appointed based on their results, and the entire process was authorized by the German military or civil administration operating nearby. [6] Here and there, recruitment to the police took place under direct compulsion: Young men were summoned to a village administration and simply told they were supposed to serve in the police from that moment on. In the event of refusal, the offender risked being sent to the nearest branch of the German state security agencies. But in the vast majority of cases, recruitment on the provincial level was voluntary, although people's motives differed even then. Some feared for their own and their relatives' lives because of possible repressions, while others collaborated out of firm ideological principles. [7]

The creation of paramilitary detachments in large populated areas was usually initiated by members of nationalist organizations and by émigrés or local veterans of the revolutionary period. For example, in Ukrainian oblasts bordering on the territory of the RSFSR, the police leadership was frequently composed of White émigrés and Russian nationalists from the National Labor Alliance of the New Generation (NTSNP; or National Alliance of Russian Solidarists). Nevertheless, there is no doubt that the dominant political force in the occupied territories of Ukraine was the OUN. In the summer of 1941, so-called expeditionary groups of Banderites and Melnykites followed in the wake of the Wehrmacht's advance units. Marching in small groups, they penetrated captured Soviet cities, where they quickly sought to establish their control. More preoccupied with the battles raging on the front line than with politics, the interim German military administration did not object to the assistance offered by the nationalists. On the contrary, autonomous paramilitary detachments assisted in the struggle against scattered hotbeds of Soviet resistance in the rear. In addition, shared viewpoints (like anti-Sovietness) helped the nationalists forge cooperation with the Germans, which, however, was not limited to the ideological dimension. Many OUN members and émigrés worked as translators in army and police units or were active associates of the German intelligence agencies (Abwehr). [8]

The adherents of the Banderite wing thus managed to organize paramilitary detachments in most large populated areas of Western Ukraine, particularly in Lviv, Rivne, Lutsk, Ternopil, and other cities. However, the repressions that the Germans launched against the members of the OUN(B), provoked by the proclamation of the Act of Restoration of the Ukrainian State on 30 June 1941, gradually weakened their organizational capacity. Even though the repressions increased in intensity with every passing month, it is difficult to state unequivocally that there was some kind of aggressive resistance on the part of the German army to the formation of local paramilitary detachments by the nationalists. This may be explained above all by the difference between the occupation regimes. For example, there was a more preferential attitude toward the local Slavic population in the military administration zone, which led to concessions regarding the creation of auxiliary military and police formations.

Be that as it may, the repressions against the Banderites prevented them from expanding their influence effectively beyond Western Ukraine. Later, the OUN's Melnykite wing members succeeded in seizing the initiative in some other regions. OUN(M) members who professed — at least publicly — a more moderate course of collaboration with the Germans were not subject to mass repressions at least until late November 1941. Thus, they managed to form police forces in many oblast centers east of the Zbruch River: in Khmelnytsky, Vinnytsia, Zhytomyr, and even Kharkiv. [9] However, the OUN(M)'s most important ideological victory was its nearly absolute dominance in Ukraine's capital, a city that was sacred to the nationalists.

Melnykites succeeded in forming a militia within days after advance Wehrmacht units entered Kyiv on 19 September 1941. Over the next few months, they created a preliminary structure (a headquarters that initially controlled thirteen, then eleven police districts in the city) and boosted their influence thanks to newly-arrived members of the Melnykites' Bukovynian Battalion. According to German police estimates, as of late October 1941, there were 1,100 auxiliary policemen at the disposal of the Kyiv authorities. [10] In addition to nationalists, leading positions were held by émigrés from the period of the 1917–1921 Ukrainian Revolution. Noteworthily, military and political émigré circles established the Ukrainian General Council of Combatants on 29 June 1941 to coordinate and dispatch volunteers deep into German-occupied territories of Ukraine. Thanks to a well-established network of contacts, all independence-seeking émigrés were immediately appointed to positions of advantage in the administrative apparatus, especially the police. [11]

Structural reorganization

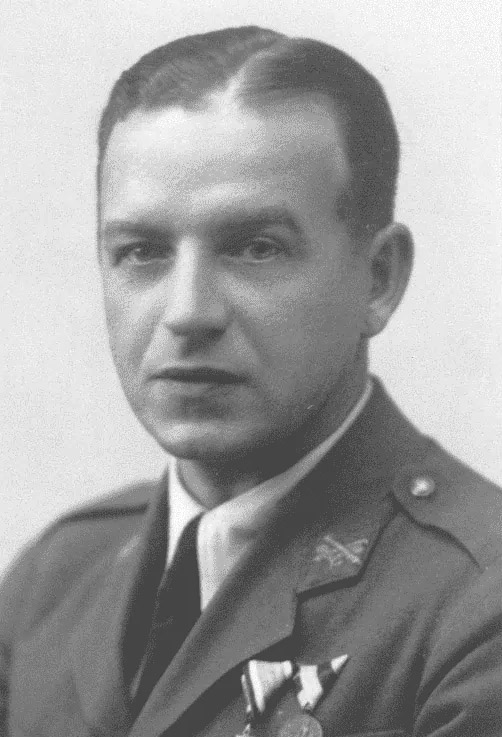

The moderate autonomy that German military commanders on the ground granted to these paramilitary detachments was canceled with the arrival of a civilian administration. Reichsführer-SS Himmler, whom Hitler directed to organize a police apparatus in the occupied territories of the USSR, was critical of granting any kind of military and political autonomy to the local Slavic peoples. Himmler himself formulated the main organizational concept for the auxiliary police in these territories: the urgent creation of a single leadership over detachments that would no longer be connected with each other. [12] The idea was clearly to preclude attempts by non-German political organizations to establish total control over the paramilitary detachments. Himmler's implementation of this concept may be seen in the fact that, unlike the German police, the UAP's hierarchical structure lacked the highest positions, the ones on the district (okruha), oblast, and national levels. The highest administrative level of the Ukrainian police, even outside the borders of Reichskommissariat Ukraine, was limited to a city and raion center. Severe punishment was meted out for violations of established regulations. The arrest on 27 February 1942 of Kyiv police chief Hryhorii Zakhvalynsky (a veteran of the UNR Army, a French émigré, and Melnykite), whom the German Security Police accused of attempting to subordinate police detachments in other raions to his control, is telling in this respect. [13] Thus, a restricted structure, together with the lack of communication between police chiefs in various raions or cities, facilitated political control over the UAP.

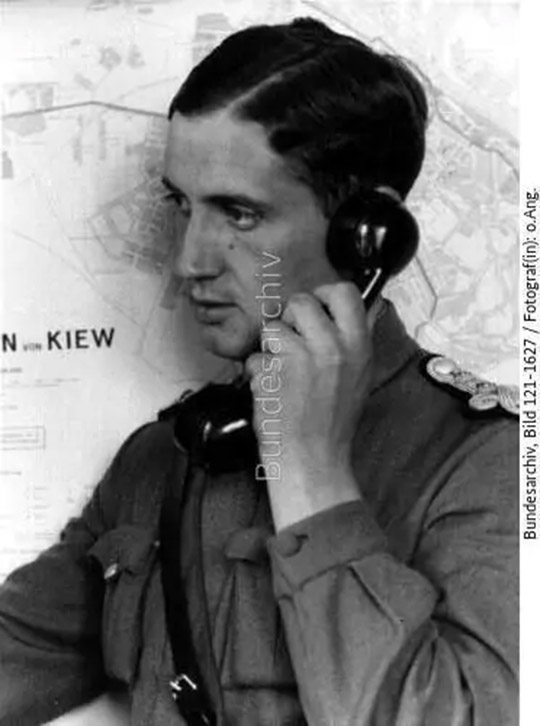

Granting independence to Ukraine, the long-cherished dream of OUN members and other actors in the pro-Ukrainian camp, was not part of the Germans' colonization plans. The propaganda image of Germans as "liberators of the local peoples from Bolshevism," which they disseminated throughout the information sphere, had nothing in common with the established occupation regime. Thus, when civilian administrations supplanted the military authorities, an ideological "correction" of the administrative apparatus began. In keeping with Himmler's order of 6 November 1941, the nationalists' paramilitary detachments were to be transformed into an auxiliary police force. After that, all police authority passed into the hands of the Germans, and a German supervisory officer was attached to every local auxiliary police commander. At the same time, German state security agencies launched a filtration of police cadres. A number of diverse German institutions operating in Kyiv and its vicinities were engaged in ferreting out "disloyal elements." The 730th Secret Field Police (Feldpolizei) under the military administration operated in urban areas, while Sonderkommando 4a and Einsatzkommando 5 operated in Kyiv. After the arrival of civilian administration, information collected by all agencies, as well as the role of the chief implementer of repressive and punitive policies in the region, would be transferred to the Security Police and the SD (Sipo/SD). The leadership of this newly created, unified body was assigned to SS-Obersturmbannführer Erich Ehrlinger, former commander of Einsatzkommando 1b. [14]

A network of secret agents reported manifestations of disloyalty among policemen, with a particular focus on the activities of the Ukrainian nationalists. In late November 1941, SS-Obersturmbannführer August Meier, commander of Einsatzkommando 5, issued an order for the immediate arrest of all well-known members of the OUN(B) whom, "following detailed interrogation [it was necessary] to liquidate quietly as outlaws." Although the OUN(B) had no influence on the Kyivan police, information about executions of police staff at this moment in time contained accusations of their assistance to arrested Banderites. At the same time, unlike the Banderites, the members of the OUN's Melnykite wing, specifically the Bukovinian Battalion, were viewed by the Germans as the most reliable of all UAP staffers in Kyiv. [15] However, the "honeymoon" period between the OUN(M) and the Germans was short-lived, as the Security Police and the SD had detained many prominent Melnykites by December 1941. Arrests of OUN(B) members resumed and intensified in February 1942, and nationalists who had managed to evade repressions were forced to flee or go deeper underground by April. Similar repressions took place in every large Ukrainian city, especially Kharkiv, where arrests of nationalists began in the summer of 1942. [16]

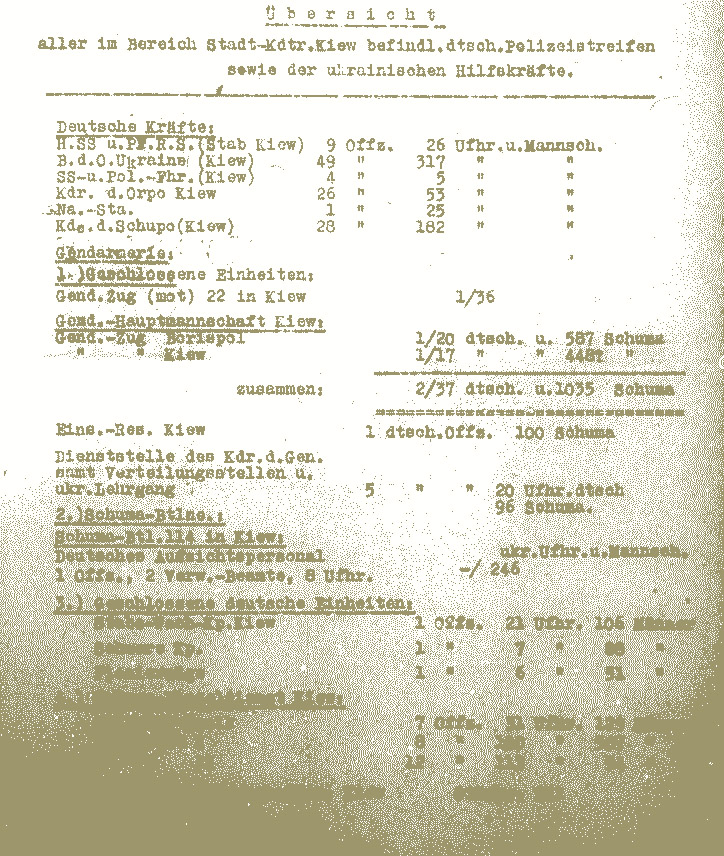

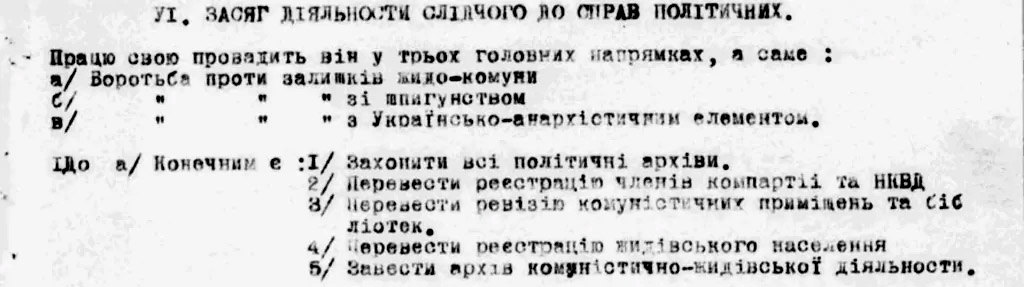

In addition to the superficial filtration of personnel, the reorganization also affected the UAP's structure. In the largest cities, it was divided into several important institutions with their own leadership and nature of duties: 1) Ukrainian Protective Police (Schutzmannschaft-Einzeldienst), whose members carried out patrolling, guarding, protecting, and other auxiliary functions. Various sources and literature mention mainly the Ukrainian Protective Police because its members also served as an urban and rural police force; 2) so-called "closed units" (Geschlossenen Einheiten der Schutzmannschaft), which functioned as mobile formations of the auxiliary police. Besides carrying out protecting tasks, these units were formed chiefly to fight against Soviet partisans, and their place of deployment changed frequently (for example, beginning in late August 1942, the 115th and 118th auxiliary police battalions were gradually transferred to Belarus); 3) Ukrainian Criminal Police (Sicherheitsschutzmannschaft,). Unlike the first two institutions, Ukrainian Criminal Police agents and investigators were part of the Department of the German Security Police and the SD, which was determined by the nature of their activities. They conducted criminal investigations and pursued political cases against communists, Jews, and nationalists; 4) well-staffed auxiliary fire brigades (Feuerschutzmannschaft) as well as local functionaries of the German river police (Wasserschutzpolizei) and camp policemen, who fought fires and carried out protective functions.

This division was practically absent on the provincial level due to a staff shortage. Thus, the functions of upholding law and order, investigating, conducting anti-partisan operations, and participating in punitive detachments were all simultaneously placed on the shoulders of the Ukrainian Protective Police and its commanders in the gendarmerie (German rural police). Against the backdrop of the rising partisan threat, police reorganization in the countryside proceeded in the direction of enlarging and creating bases (Stützpunkten). In 1942–1943, staffers based in several villages (from three to nine) began to be merged into so-called kushch units that could constitute at least some kind of force in the event of an attack by Soviet partisans. [17]

A collective portrait of police employees

The question of the UAP's personnel requires separate, thorough research, but some generalizations can still be made. In a provincial locality, the Ukrainian police were distinguished by their homogeneity and the absolute predominance of locals with their stable, patrimonialist characteristics (kinship, nepotism). For example, the average Ukrainian Protective Police employee in Makariv district, located on the outskirts of Kyiv, was a married, 25-year-old local peasant. Ukrainians filled the position of post commander and most rank-and-file positions, and up to 10 percent of the personnel consisted of people of other ethnicities, like Volksdeutsche translators. [18]

In large cities like Kyiv, a dominant majority of rank-and-file positions in the Ukrainian Protective Police were held by ordinary young workers and peasants from the city and its vicinities, who had ended up in the police voluntarily or under the pressure of adverse circumstances (the threat of dying in a POW camp, instead of being sent to forced labor in Germany, etc.). However, the situation with leading cadres was different. It has already been stated that, despite the Germans' repressions, throughout the entire occupation of Kyiv, approximately 70 percent of the top positions in the Ukrainian Protective Police were held by nationalists, émigrés, and veterans of the 1917–1921 Ukrainian Revolution. The perennially large concentration of representatives from the "pro-Ukrainian" camps, clearly conditioned by their view of Kyiv's sacrality, is unique. The situation in other large cities was different. At present, it is difficult to explain why such a large number of people, potentially hostile to the Germans, remained "undetected" by the occupation state security organs.

The collective portrait of half of Kyiv's "closed units" (the 115th and 118th battalions and a company armed with heavy weapons) resembled that of the Ukrainian Protective Police, the sole difference being that their rank-and-file personnel included a large number of former Soviet POWs from all over Ukraine. For them, the threat of death by starvation was conceivably their primary motive for joining the police because, in December 1941 alone, nearly 2,500 Red Army soldiers were dying every day in POW camps based in Ukraine. [19] Soldiers clearly sought any way to stay alive; thus, a policeman's work could seem like salvation to them.

In contrast, the Ukrainian Criminal Police personnel in Kyiv included hardly any Ukrainian nationalists, let alone émigrés. Instead, in the spring of 1942, criminal and political cases were often investigated by former Soviet activists: communists, Komsomol members, NKVD personnel, lawyers, and Volksdeutsche. The Security Police and the SD scrupulously approached the selection of auxiliary cadres from among local people; hence, many pro-German informers were concentrated in the ranks of the Ukrainian Criminal Police specifically. [20]

As of January 1942, the UAP in the Kyiv General District had a staff of 4,800, while the average number of policemen in a single district — for example, Makariv — topped the hundred-person mark. By early 1943, the total number tripled, and the Kyiv Ukrainian Protective Police alone numbered more than 1,400 employees. That said, these estimates do not include the "closed units" that were based in Kyiv during this period (over 500 people) or the Ukrainian Criminal Police (up to 200 people). [21]

From ordinary assignments to violent practices

For the most part, Ukrainian policemen dealt with duties typical of law enforcement agencies: performing guard post duty, protecting important installations, investigating crimes, etc. For example, in Kyiv, the Ukrainian Protective Police patrolled the streets around the clock, responding to citizens' statements and challenges, while the fighters of "closed units" guarded important administrative, industrial, and military installations. The Ukrainian Criminal Police staff investigated administrative or criminal cases, releasing defendants or sending them to court. Despite representing the lion's share of police work, such routine matters are of little interest to researchers. However, auxiliary police bodies were never formed for the purpose of carrying out law enforcement functions in the usual sense. In fact, the very notions of "ensuring peace" and "law enforcement" in the context of German occupation policies were euphemisms for repressive and punitive measures, and these are worth examining in greater detail.

Eyewitnesses of the occupation remember Kyiv's markets as places where mass violence took place. Under the supervision of the German Schutzmannschaft, the Ukrainian Protective Police regularly conducted roundups in order to deport locals to forced labor in Germany. In January 1942, the German authorities launched a propaganda campaign designed to motivate the local population to join the ranks of the so-called Ostarbeiter. By April, the principle of volunteerism morphed into brutal coercion. In order to meet the German leadership's quota of 360,000 forced laborers for the Kyiv General District, the occupation administration resorted to its largest instrument: the Ukrainian police. [22] Between 1 April and 10 June 1942, the UAP in Kyiv's Sofiivsky district alone detained and dispatched 1,363 unemployed people to medical commissions for their potential selection as workers. Arrests carried out according to lists prepared in advance by a district administration eventually turned into mass roundups that took place at marketplaces in Kyiv and other areas where many people congregated. Eyewitnesses recall that during one such roundup at Halytsky Market, policemen detained nearly a thousand people. [23]

Another reason for conducting roundups at city marketplaces was confiscating sellers' goods. Each Ukrainian Protective Police post set up at the entrances to Kyiv served as a kind of customs office, where policemen could confiscate whatever foodstuffs they wanted from people seeking to enter the city. The policemen either seized the confiscated items or food for themselves or sent them to a district police building, where the staff divided them up amongst themselves. [24] On the whole, the incidence of arbitrariness in the form of misappropriation of property, especially during the transitional stage (the first months of the occupation), occasionally reached epic proportions and is corroborated by various sources. One written complaint states that Pavlo Bandura, commandant of the Sviatoshyn district police, misappropriated a piano and apartment furnishings. According to the complainant, "P. Bandura considers himself the 'sovereign dictator' of Sviatoshyn." Ivan Dobrovolsky, commander of the Kurenivka district police, and Yakiv Kiriushenko, commandant of the Darnytsia district police, were accused of similar crimes. [25] All three were dismissed from the Ukrainian Protective Police by February 1942.

Police participation in "political" arrests

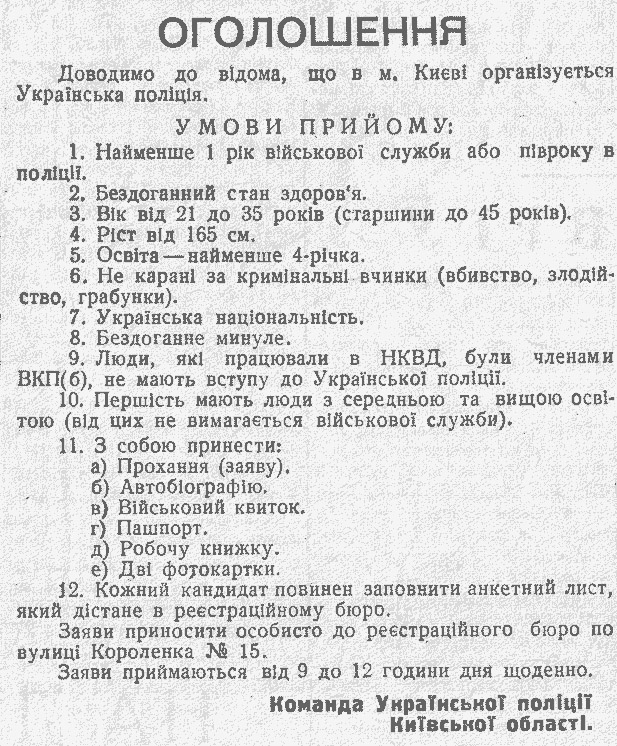

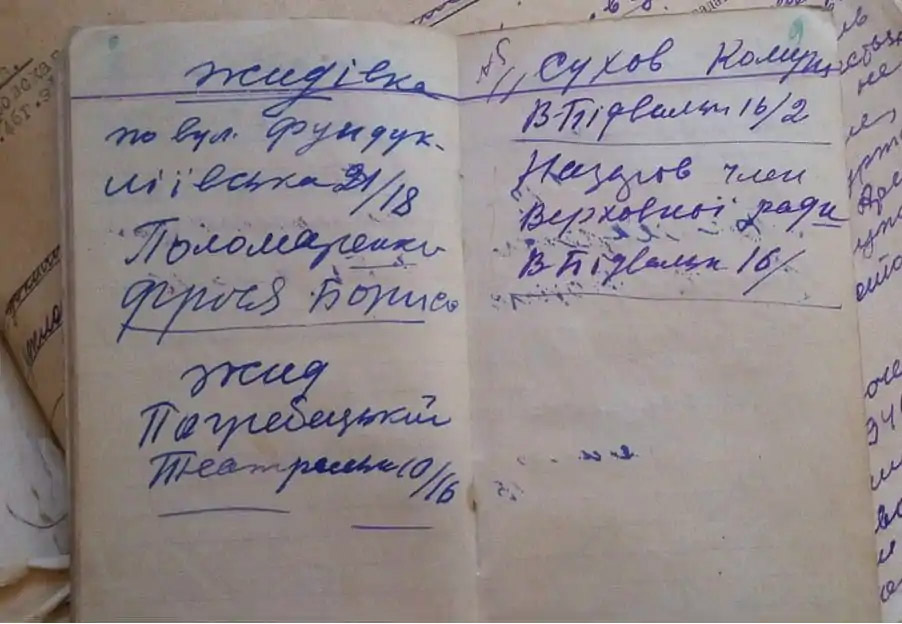

Thus far, not a single source that would reliably attest to the UAP's direct participation in the mass shootings in Babyn Yar on 29–30 September 1941 has been found. German units carried out the shootings while Ukrainian policemen sorted through the victims' clothing. The shootings were followed by a hunt for Jews who had managed to hide. In the first days of October 1941, the city commandant, Major General Kurt Eberhard, signed an order directing all former NKVD personnel, as well as members of the Komsomol and the Communist Party, to register within 24 hours at the Ukrainian police headquarters (15 Korolenko Street). [26] That was when the Germans required the assistance of the local UAP. According to an order issued by the city police commander Anatolii Konkel on 18 October 1941, building superintendents and janitors were obliged, under pain of death, to inform the occupation organs about all known Jews and Soviet activists. The testimonies of Ukrainian policemen confirm that Konkel's order was carried out, and the policemen were actively involved in the arrests. [27] After preliminary questioning and checks by the Ukrainian police, Jews were sent to the headquarters of the Security Police and the SD located at 33 Korolenko Street. After being interrogated there, they could expect either to be executed or (starting in the spring and summer of 1942 ) imprisoned in the Syrets camp. [28]

Unlike Jews, whom death awaited one way or another, former representatives of the Soviet political system had an incomparably greater chance of survival. If they registered voluntarily, they were not subject to repressions. However, this did not necessarily offer them absolute security because the arrests of registered communists became widespread in the last months of the occupation of Kyiv. Every department of the UAP had a special filing cabinet containing the names of all former Soviet representatives. For example, a single investigator in the Darnytsia district police had the names of 175 members of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) (VKP[b]). [29] About twice a month, a registered individual had to appear at the department and complete mandatory reregistration; otherwise, s/he would be placed on the Wanted List.

In addition to Jews and Soviet activists, the Germans also regarded OUN members as "political enemies." The December 1941 arrests of nationalists resumed with renewed vigor after the arrival of SS-Obersturmbannführer Erich Ehrlinger in late January 1942. His first conspicuous victim among the UAP personnel was the "investigative department" chief and OUN(M) member Roman Bida. The "investigative department" Bida had headed was placed under Ehrlinger's supervision soon afterward and included in the Ukrainian Criminal Police in March 1942. Part of its structure was a "political department," whose agents and investigators carried out repressions against the nationalist underground, in addition to arresting Jews and communists. Evidence indicates that the Skuz brother agents "pursued" a case against Dmytro Myron, krai leader of the OUN(B). On 24 July 1942, they shot him while he was attempting to escape. Even though the "Banderites" announced that they had succeeded in exacting revenge on the killers, Leonid Skuz, for one, continued to work in the "political department" of the Ukrainian Criminal Police. [30] Another agent, Heorhii Puzenko, was assigned to follow a group of nationalists embedded in the police. Based on information obtained from Puzenko in March 1943, members of the Security Police and the SD carried out large-scale arrests, during which they executed the police leadership of Volodymyrsky district, including Commandant Anatolii Odarchenko. [31]

The situation was not the same in cities and small populated areas, which should be borne in mind. Living in a socially closed milieu, all the inhabitants of a village knew each other, which led to large-scale acts of violence against Jews as well as against former members of the Soviet political system. Whereas city policemen did not know their victims personally for the most part, detailed lists of Jews and communists were drawn up in rural areas, along with a description of each person. This information was then handed over to the German authorities in the region. [32] The shortage of German rural police personnel led to a situation in which the rural Ukrainian Protective Police did almost all the work of the Germans: imprisoning, convoying prisoners, and sometimes shooting. For example, in October 1941, members of the Dymer and Makariv district police (vicinity of Kyiv) convoyed no fewer than 77 detained Jews, including children, to the camp on Kerosynna Street in Kyiv. Shortly afterward, the Germans executed all of them. One and a half months later, 36 Jews and three Soviet activists were in the Makariv district police prison; it goes without saying that the same fate awaited them. [33]

According to the historian Alexander Prusin, UAP members were directly or indirectly involved in the Holocaust in all boroughs of the Kyiv General District. [34] It seems that the Kyiv District Area (Kreisgebiet Kiew) and the city itself (Kiew-Stadt) were no exception. According to existing information, between August and December 1941, Ukrainian policemen took part in the shootings that took place in all suburban areas (Makariv, Borodianka, Byshiv, and partly Dymer), as well as in Lukianivka Cemetery in Kyiv. [35] Furthermore, unlike the work of the city police, the activities of the rural police were practically not controlled. A permissive atmosphere arose, which led to acts of spontaneous violence. Around August 1941, three policemen in Byshiv district were ordered to detain a four-member Jewish family, including a child. Instead of bringing them to the station, the policemen decided to shoot them and divide the looted property amongst themselves. A similar incident took place near the urban-type settlement of Bucha, where four UAP members detained one man and two women of Jewish nationality. At first, the policemen led them to the woods, where they raped the youngest of the Jewish women. When they finished, they killed all three and seized the victims' property. In both cases, the policemen committed grievous crimes on their initiative without a direct order from their superiors. [36]

Bandenbekämpfung

The question of the UAP's participation in combating partisans (Bandenbekämpfung) remains understudied. To carry out such tasks, the Germans organized a number of auxiliary police battalions (Schutzmannschaft-Bataillonen) and other so-called "closed units." During the occupation of Kyiv, at least two companies (a company armed with heavy weapons and a headquarters company), three battalions attached to the German Protective Police (114th, 115th, and 118th), and one battalion attached to the SD (23rd) were formed. Then, no earlier than March 1942, the troops of the 115th Auxiliary Police Battalion were deployed to the vicinity of the large village of Khabne (100 km north of Kyiv). According to the policemen's testimonies, they were searching for a group of Soviet paratroopers who had been dropped over this area. In June and July of that same year, a unit of the 115th Battalion and the 1st Company of the 118th Battalion took part in similar operations in the same sector. [37] In the final days of 1942, the personnel of a Kyivan heavy company and the 23rd Battalion attached to the SD repeatedly engaged in battles with partisan detachments under the command of Kovpak, Saburov, Naumov, and Khytrychenko in various districts of the Ukrainian region of Polissia. During one such clash in December 1942, the fighters of the heavy company destroyed several large villages: "We pushed out the partisans, and burned down […] the village consisting of 100–150 residential buildings and structures." [38] In April 1943, these same forces, together with policemen from the 23rd Battalion attached to the SD, clashed with partisans in the vicinity of the urban-type settlement of Kodra. As a result of that operation, they managed to push out the partisans, after which the populated area was burned down. [39]

All three battalions were transferred to Belarus: first, the 115th, then the 118th (until late 1942), and eventually the 23rd (in late 1943). During various periods, these formations, together with German, Russian, Belarusian, and Baltic units, were involved in the biggest anti-partisan operations in the region, including those codenamed Hamburg (8–22 December 1942 ), Cottbus (17 May–21 June 1943), Hermann (13 July–8 August 1943 ), and Frühlingsfest (Spring Festival) (17 April–12 May 1944 ). [40] During the active-combat phase, all large villages near which clashes with partisans took place were burned by both German and non-German formations. Acts of mass violence accompanied combat operations. Thus, together with all other auxiliary units, the Kyivan battalions frequently took part in setting fires and looting the local population. For example, the testimonies of the participants of Operation Frühlingsfest reveal that during combing operations conducted in populated areas of Vitebsk oblast, the 23rd Battalion attached to the SD "shot partisans as well as civilians suspected of links with the partisans." [41] Thus, the "struggle against gangs," as indicated on paper, served to disguise operations in which up to 90 percent of killed "bandits" turned out to be people who had nothing to do with any clandestine organizations. [42]

The study of the UAP in Kyiv and its vicinities reveals an entirely symptomatic picture of events. Just as in western and eastern Ukraine [43], initially, the Ukrainian militia and, later, the auxiliary police that was created on its basis took part in discrete acts of mass violence in the Kyiv area, ranging from the persecution of Jews and communists to the arrests of OUN members. Collective portraits of policemen prove that anyone could become a perpetrator of violence: Ukrainian nationalists, ordinary peasants, former communists, and Soviet militiamen. Ultimately, the work of the UAP did not differ in any way from that of other auxiliary police forces that were created in German-occupied regions of Europe.

This article features photographs from the author's personal archive and open sources.

Endnotes

- Iuryi Hrybouski, “13-y batal′ion dapamozhnai palitsyi SD: Historyia stvarennia і dzeinastsi," Arche, no. 1 (2013): 281–82; Dmitrii Zhukov and Ivan Kovtun, Russkaia politsiia (Moscow: Veche, 2010), 178–79; Martin Dean, Collaboration during the Holocaust: Crimes of the Local Police in Belorussia and Ukraine, 1941–44 (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2000), 44; Jan Grabowski, Na posterunku: Udział polskiej policji granatowej i kryminalnej w zagładzie Żydów (Wołowiec: Wydawnictwo Czarne, 2020), 251.

- Alfonsas Eidintas, Jews, Lithuanians and the Holocaust (Vilnius: Versus Aureus, 2003), 168–71; Leonid Rein, The King and the Pawns: Collaboration in Byelorussia during World War II (New York: Berghahn Books, 2011), 331; Ivan Gribkov, Dmitrii Zhukov, and Ivan Kovtun, Osobyi shtab "Rossiia" (Moscow: Veche, 2011), 82–87.

- For a detailed discussion of prewar German-Ukrainian relations and more, see Kai Struve, Nimets′ka vlada, ukraїns′kyi natsionalizm, nasyl′stvo proty ievreїv: Lito 1941 roku v Zakhidnii Ukraїni (Kyiv: Dukh і Litera, 2022), 90–113.

- Grabowski, Na posterunku, 346.

- John-Paul Himka, Ukrainian Nationalists and the Holocaust: OUN and UPA’s Participation in the Destruction of Ukrainian Jewry, 1941–1944 (Stuttgart: Ibidem Press, 2021), 222–24.

- See, e.g., the State Archives of Kyiv Oblast (hereafter cited as DAKO), f. R-2053, op. 1, spr. 1, fol. 21 (“Protokol №1 zahal′noho skhodu s. Rytniv, 9.10.1941”).

- For some cases of forcible recruitment to the police in raions of Kyiv oblast, see HDA SBU, f. 5, spr. 48024, fols. 14, 56; USHMM, RG-31.018M, reel 1, frame 1264.

- For example, Melnykites were repeatedly helped by Stepan Suliatytsky, a staff member of Abwehr Nebenstelle Lviv, while coordination assistance was provided by Alfred Bisanz, a consultant to Abwehrstelle Cracow (both men were veterans of the Ukrainian Galician Army [UHA]). See HDA SBU, f. 65, spr. C-7448, fol. 14 (“Protokol doprosa osuzhdennogo Bizantsa Al′freda Ioganovicha ot 23 noiabria 1949 goda”); Iaroslav Haivas, “U roky nadiї і beznadiї”: Kalendar-al′manakh “Novoho shliakhu” (Toronto, 1977), 110.

- Struve, Nimets′ka vlada, 211, 222, 482; Himka, Ukrainian Nationalists, 258, 349.

- BArch, R 19/121, Bl. 59 (HSSPF beim Bfh. rückw. Heer. Geb. Süd., Betreifft: Hilfspolzeieinheiten. 29.10.1941). I am grateful to Andriy Usach for providing me with this document.

- Daniil Sytnyk, “Formuvannia ukraїns′koї politsiї v Kyievi (1941–1943),” Naukovi zapysky NaUKMA: Istorychni nauky, no. 3 (2020): 43.

- Ivan Dereiko, Mistsevi formuvannia nimets′koї armiї ta politsiї u Raikhskomisariati “Ukraїna” (1941–1944 roky) (Kyiv: Instytut istoriї Ukraїny NAN Ukraїny, 2012), 62, 65.

- “Uryvky z donesennia nachal′nyka politsiї bezpeky ta SD u Kyievi pro sytuatsiiu v Kyїvs′komu heneral′nomu okruzi za liutyi 1942 r. [07.03.1942],” in Kyїv ochyma voroha: Doslidzhennia, dokumenty, svidchennia, ed. V. M. Lytvyn et al. (Kyiv: Instytut istoriї Ukraїny NAN Ukraїny; Memorial′nyi kompleks “Natsional′nyi muzei istoriї Velykoї Vitchyznianoї viiny 1941–1945 rr.,” 2012), 118.

- Alexander Prusin, "A Community of Violence: The SiPo/SD and Its Role in the Nazi Terror System in Generalbezirk Kiew," Holocaust and Genocide Studies 21, no. 1 (2007): 3–6.

- “Befehl Einsatzkommando 5 an Außenposten vom 25.11.1941: OUN (Bandera-Bewegung),” in Deutsche Besatzungsherrschaft in der UdSSR 1941–1945: Dokumente der Einsatzgruppen in der Sowjetunion, ed. Andrej Angrick, Klaus-Michael Mallmann, Jürgen Matthäus et al. (Darmstadt: WBG, 2013), 239; NARA, T315, roll 2218, frame 639 (“454. Sich.-Div., Tätigkeitsbericht für den Monat November 1941, 4.12.1941“).

- Sytnyk, “Formuvannia,” 43. On the situation in Kharkiv, see Yuri Radchenko, " 'We emptied our magazines into them': The Ukrainian Auxiliary Police and the Holocaust in Generalbezirk Charkow, 1941–1943," Yad Vashem Studies 41, no. 1 (2013): 74.

- Dereiko, Mistsevi formuvannia, 69.

- Calculated on the basis of DAKO, f. R- 2001, op. 1, spr. 4 (“Osobysti lysty politsaїv Makarivs′koї raionnoї politsiї, 1941–42”).

- Wendy Lower, Nazi Empire Building and the Holocaust in Ukraine (University of North Carolina Press, 2005), 64.

- This author compiled the cited assessments on the basis of the more than 135 archived criminal cases against former Kyivan policemen, which I analyzed as part of my doctoral dissertation research.

- Based on NARA, T501, roll 349, frame 554 (“GFP 706, Tätigkeitsbericht für Monat Januar 1942, 25.01.42”); USHMM, RG-31.059M, reel 2, frame 721 (“Gend.-Posten-Kiew-Land, Einteilung der Schutzmannschaften im Rajon Makarow, 8.01.1942”); NARA, T315, roll 1634, frame 958 (“Übersicht aller im Bereich Stadt-Kdtr. Kiew befindlich deutschen Polizeistreifen sowie der ukrainischen Hilfskräfte, 5.03.1943”); HDA SBU, f. 11, spr. 769, vol. 14, fols. 127–33 (“Spysok na oderzhannia paika spivrobitnykiv Politsiї Bezpeky, Kryminal′nyi viddil m. Kyieva, z 1 serpnia po 10 serpnia 1943 roku”).

- For detailed discussion of Ostarbeiters, see Tetiana Pastushenko, Ostarbaitery z Kyїvshchyny: Verbuvannia, prymusova pratsia, repatriiatsiia (1942–1953) (Kyiv: Instytut istoriї Ukraїny, 2009).

- DAKO, f. R-2412, op. 2, spr. 19, fol. 132 (“Vidomosti pro nadsylku bezrobitnykh po sushchakh”); Sytnyk, “Formuvannia,” 43.

- For example, HDA SBU, f. 5, spr. 61301, fols. 27v–29.

- DAKO, f. R-2356, op. 1, spr. 53, fols. 7–7v (“Do Holovy Mis′koї Upravy [6.11.1941]”); DAKO, f. R-2356, op. 1, spr. 53, fol. 74 (“Do zhytlovoho viddilu Kurenivs′koї raiupravy, 21.01.1942”); HDA SBU, f. 13, spr. 397, fols. 23–27 (“Istoriia organizatsii Ukrainskoii politsiї Darnitskogo raiona [18.08.1942]”).

- USHMM, RG-31.026M, reel 21, frame 939 (“Informatsiia o sostoianii raboty Kievskoi podpol′noi organizatsii KP(b)U, 28.03.1943”).

- HDA SBU, f. 5, spr. 60916, fol. 16; HDA SBU, f. 5, spr. 59660, fol. 10v; Kost′ Himmel′raikh, Spohady komandyra viddilu osoblyvoho pryznachennia “UPA-Skhid” (Toronto: Litopys UPA, 1987), 117

- For detailed discussion of all the stages of an arrest from the victim's perspective, see Zachar Trubakov, USHMM, Oral History, 1995. A.1272.158, RG-50.120.0158.

- HDA SBU, f. 5, spr. 56580, fol. 15; HDA SBU, f. 5, spr. 28711, fol. 92.

- “Khronika-spohad ‘U zlatohlavomu’; Sichen′ 1948 r. (Natalka Tyrsa)," in Litopys UPA, n.s., vol. 18, Diial′nist OUN ta UPA na terytoriї Tsentral′no-Skhidnoї ta Pivdennoї Ukraїny (Toronto: Litopys UPA, 2011), 648, 662–63.

- HDA SBU, f. 5, spr. 61018, fol. 42; HDA SBU, f. 5, spr. 46829, fols. 56–58.

- DAKO, f. R -2053, op. 1, spr. 2, fols. 3–3a (“Vidomist′ hrazhdaniv, iaky [sic] pidliahaiut′ zahrozhennia sela”).

- HDA SBU, f. 5, spr. 39840, fol. 38; USHMM, RG-31.059M, reel 2, frames 609, 729; ibid., RG-31.08M, reel 3, frame 1133.

- Aleksandr Prusin, “Ukrainskaia politsiia i Kholokost v general′nom okruge Kiev, 1941–1943: Deistviia i motivatsii,” Holokost і suchasnist′; Studiї v Ukraїni і sviti, no. 1 (2007): 41.

- HDA SBU, f. 5, spr. 39840, fol. 34; HDA SBU, f. 5, spr. 43555, fol. 48v, 79; HDA SBU, f. 6, spr. 69330 fp, fol. 44.

- RG-31.08M, reel 4, frame 226; HDA SBU, f. 5, spr. 48024, fol. 88.

- Andrii Duda and Volodymyr Staryk, Bukovyns′kyi kurin′ v boiakh za ukraїns′ku derzhavnist′, 1918–1941–1944 (Chernivtsi, 1995), 121–23, 144; HDA SBU, f. 5, spr. 60030, fol. 17v.

- HDA SBU, f. 5, spr. 57745, fol. 16.

- HDA SBU, f. 5, spr. 59693, fol. 49.

- There are mentions of this in some sources. See BArch, R 70-SOWJETUNION/14, Bl. 61–2 (“Einsatzbefehl für das Unternehmen ‘Hermann,’ 7.7.1943”); BArch, RS 3-36/8, Bl. 149 (“Die HSSPF Rußland-Mitte und Weißruthenen, Kräfteübersicht, 1.06.1943”); NARA, T354, roll 651, frames 582–83 (“Einsatzbefehl für Unternehmen ‘Frühlingsfest,‘ 11.04.1944”); NARA, T354, roll 651, frames 557–58 (“Sonderbefehl, Einsatz der Sicherheitspolizei und des SD. bei Unternehmen ‘Frühlingsfest’ und Belehrung für die Truppe, 10.04.1944”).

- USHMM, RG-06.025, reel 14, frame 622 (“Protokol doprosa leitenanta Menge Val′demar Gugo, 5.02.1946”).

- Per Anders Rudling, "Terror and Local Collaboration in Occupied Belarus: The Case of Schutzmannschaft Battalion 118. Part One: Background," in Historical Yearbook 8 (2011), 205

- Gabriel Finder and Alexander Prusin, “Collaboration in Eastern Galicia: The Ukrainian Police and the Holocaust,” East European Jewish Affairs 34, no. 2 (Winter 2004): 95–118; Iurii Radchenko, “Ukraїns′ka politsiia ta Holokost na Donbasi,” Ukraїna Moderna, no. 24 (2017): 64–121.

Daniil Sytnyk is a graduate student at the Yukhymenko Family Doctoral School of the National University of Kyiv-Mohyla Academy ([email protected]). He is the recipient of numerous scholarships, including the Mandel Center Alumni of the Ukrainian Summer Programs (Mandel Center for Advanced Holocaust Studies, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum). His research interests include the study of collaborationism in Eastern and Southern Europe during the Second World War, the structure of the SS and the police of the Third Reich, and the history of the Holocaust. He is currently working on his doctoral dissertation, "The Ukrainian Auxiliary Police in the City of Kyiv: Formation, Activity, and Cadre Personnel, 1941–1945."

Daniil Sytnyk is a graduate student at the Yukhymenko Family Doctoral School of the National University of Kyiv-Mohyla Academy ([email protected]). He is the recipient of numerous scholarships, including the Mandel Center Alumni of the Ukrainian Summer Programs (Mandel Center for Advanced Holocaust Studies, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum). His research interests include the study of collaborationism in Eastern and Southern Europe during the Second World War, the structure of the SS and the police of the Third Reich, and the history of the Holocaust. He is currently working on his doctoral dissertation, "The Ukrainian Auxiliary Police in the City of Kyiv: Formation, Activity, and Cadre Personnel, 1941–1945."

Originally appeared in Ukrainian @Ukraina Moderna

This article was published as part of a project supported by the Canadian non-profit charitable organization Ukrainian Jewish Encounter.

Translated from the Ukrainian by Marta D. Olynyk.

NOTE: UJE does not necessarily endorse opinions expressed in articles and other materials published on its website and social media pages. Such materials are posted to promote discussion related to Ukrainian-Jewish interactions and relations. The website and social media pages will be places of information that reflect varied viewpoints.