"These people aimed to prove that Jewish art existed." Lviv's Jewish artists in the early 20th century

Art critic Bohdana Pinchevska talks about secular Jewish art of Eastern Galicia in 1900–1939.

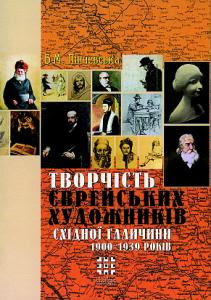

Bohdana Pinchevska's book on secular Jewish art

Yelyzaveta Tsarehradska: Today, we will talk about your book. This book, I'm sure, is of interest to a broad audience as it tells the story of how secular Jewish art emerged in Lviv, the central city of Eastern Galicia, in 1900–1939.

In the "Encounters" program, we try to travel back in time and recreate the atmosphere, understand the context, immerse ourselves in those circumstances, and consider the legacy of historical periods. Hence my first question: What sparked your interest in the 1900–1939 period? What makes it stand out from the rest? How did you come to write an entire book on the topic?

Bohdana Pinchevska: I am quite happy with your concept of time travel. This was one of the factors that made me write my book. It all started with the fact that NAOMA [National Academy of Fine Arts and Architecture. — Ed.], which I graduated from, had a rule that research topics had to be about something located in Ukraine. It was highly recommended and actually forced on us. I scanned all of Ukraine in my mind and settled on a topic that annoyed me the least. One that had nothing to do with the USSR at all. The only way anything Soviet could find its way to Lviv in that period was through occasional translations in some newspapers, and that was it. That was my first reason.

Second, I was considered a promising art critic because my late teachers at NAOMA told me: "Write a thesis, and we'll make sure you defend it." By the time I finished the work, they had all passed away, unfortunately. And it was important for me to justify their trust.

Third, I chose a topic that was interesting to me. I was not so interested in pursuing a career as a PhD in art history as in solving a research problem. And I finally found it. I looked carefully at some materials and realized that people who were often not acquainted with each other created a distinct trend in art out of nothing within roughly three generations. They crafted Jewish secular art where there was none. I was eager to find out how they did it, what methods they used, and what they did to create a distinct ethnic trend in art, which is still exciting to discuss at conferences and elsewhere. That is why I chose this topic.

In short, my formula was an exciting topic minus Soviet stuff.

Prerequisites for emergent secular Jewish art in the early 20th century

Yelyzaveta Tsarehradska: When something is created from scratch, there has to be some impulse, background, or a trigger. In our case, was it a human factor or some events?

Bohdana Pinchevska: As always, these were events and phenomena that prompted certain people to behave in a certain way.

Yelyzaveta Tsarehradska: Who were those people?

Bohdana Pinchevska: The cultural prerequisite was that the Jewish sector appeared at one of the European industrial and art exhibitions in Paris in the 19th century. It contained Jewish decorative, applied, and sacred art. This was the first time it was brought to an international of this stage caliber. Some artists, Jews by origin, did not hesitate to periodically depict their environment, mainly religious Jewry, in the form of domestic scenes, ceremonial portraits, and historical subjects.

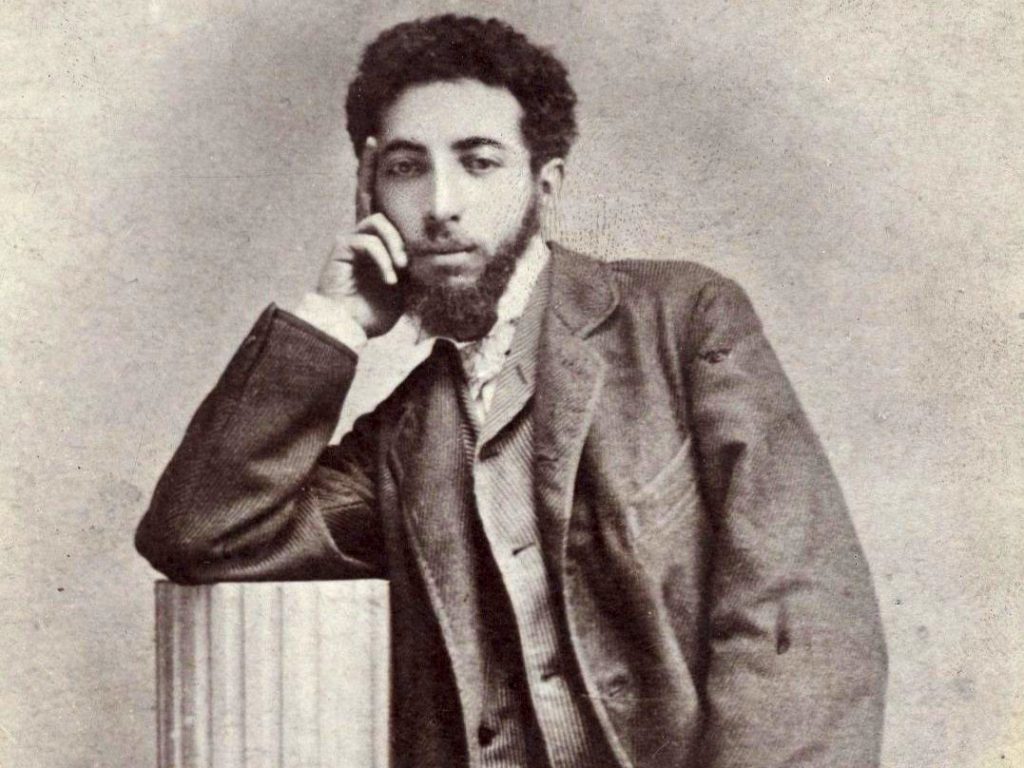

The background was that the Kraków School of Fine Arts, the top art institution in Galicia for aspiring painters, accidentally launched a line of Jewish art in the 19th century. It occurred when Maurycy Gottlieb, the son of an oilman, came from Drohobych to Kraków to study under Jan Matejko, who headed the school at the time. Gottlieb turned out to be such a talented student and so deeply understood the concept of national Polish art and Matejko himself that, after Gottlieb's early death, Matejko admitted Jewish applicants without any restrictions. Poland, particularly Kraków, knew nothing like the barbaric faith-based restrictions on enrollment as those that existed in the Russian Empire.

The Kraków School of Fine Arts was renamed the Kraków Academy of Fine Arts in 1900. So, I used this year as the starting point for the period I was particularly interested in. It was the region's first professional higher education institution, the alma mater of nearly all Jewish artists who later became renowned and were mentioned in textbooks on this topic.

Territorial affiliation of secular Jewish artists

Yelyzaveta Tsarehradska: What part of Galicia have you analyzed in your book?

Bohdana Pinchevska: A Polish researcher wrote a monograph on the Jewish art of Western Galicia and Kraków, so I limited myself to Lviv only. All the artists I wrote about studied at the Kraków Academy (previously, School) of Fine Arts. Upon graduation, they would spread across Western Europe, going to Austria, Germany, France, etc., and continuing to refine their education in Western Europe.

All Jewish artists from what is now the Lviv region studied at least a few semesters in interwar Kraków.

To add a few finishing touches to this foundation, Jan Matejko, a Pole, a workaholic, and a fascinating artist, had a very simple vision of how to shape national art. It had to be done through dedicated depiction of key moments in the history of a certain people, including momentous historical events and major figures. Maurycy Gottlieb, his favorite student, grasped this idea best, which is why he is tentatively considered the father of Jewish secular art. Entire libraries of works have been written about him abroad. In contrast, not a single monograph has been published about Gottlieb in Ukraine, even though he was born in Drohobych. Honestly, this is shocking, as a figure of his proportions surely deserves at least a thin book.

What secular art is

Yelyzaveta Tsarehradska: What is secular art?

Bohdana Pinchevska: Secular means non-religious in this context. For a very long time, until the beginning of the 20th century, Jewish art was thought to include decorative and applied art, having to do with the ceremonial celebration of Jewish holidays, but not painting or graphics.

Then, a generation of non-religious artists who received secular education emerged. Of course, they entered Judaism in the column "Religion" in the application forms for the Kraków or Warsaw Academy of Fine Arts. However, this was the religion of their families, while they were modern, lively, young, and very curious people who wanted to become artists above all else.

How Galician society viewed secular Jewish art

Yelyzaveta Tsarehradska: Was there opposition to their art in Galicia?

Bohdana Pinchevska: The Galician community had no particular objections. Jewish art emerged from collaboration and focused and consistent activities of artists, teachers, columnists, art collectors, partly museum workers, and exhibition organizers. Ideologues and politicians sometimes joined them, which was an important, but not crucial, factor.

These people aimed to prove to everyone around that Jewish art existed. They were often told that it could not. And this came not only from antisemites but also from ordinary folks like neighbors across the street.

Yelyzaveta Tsarehradska: Were those stereotypical visions of that time? What was the problem?

Bohdana Pinchevska: This problem was first described in an article on Jewish art by Mykola Holubets, the most courageous Ukrainian art critic. He analyzed what he read in the newspapers in the 1920s and 1930s. It was a brave act. Only a figure of such magnitude as Holubets, with his huge bibliography and authority, could afford to speak calmly on this topic.

He justified his doubts by the fact that there was no land where Jews lived. There was no Israel then, and the Holocaust was still far away. Accordingly, Jews constantly studied in different universities in different countries. He analyzed this issue very calmly, noting that Jewish students studied in French, German, and Polish universities. Accordingly, they left those institutions as people who represented the cultures that shaped them, from a purely technical viewpoint.

That an artist who studied in Lviv could be referred to as a 'Lviv artist' rather than a 'Ukrainian artist,' which resulted in a complete shift in perspective and perception of ethnic identity, was proposed as late as the 1930s when the Artes association became active. One of its members suggested linking some Jewish works to toponyms, which greatly facilitated the work of art historians in later periods.

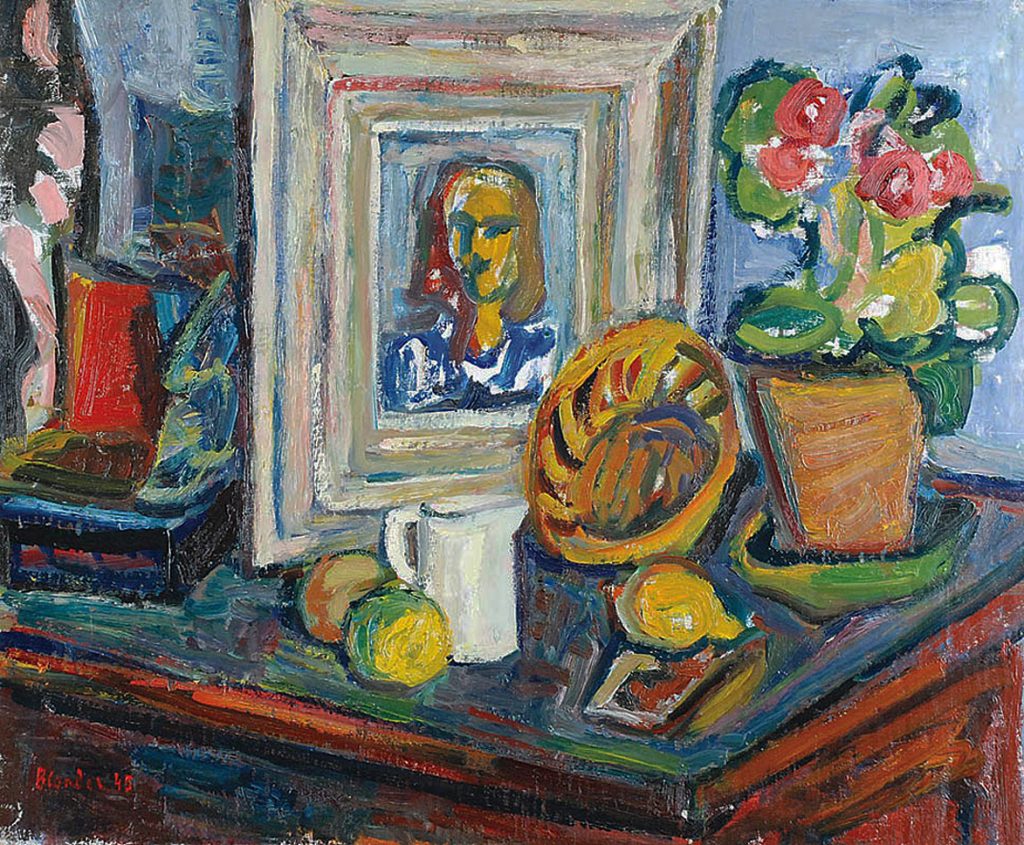

In general, even if these Jewish artists had any domestic conflicts because they became secular, learned to paint, and theoretically risked violating one of the commandments, no memoirs or surviving documents testify to this. Meanwhile, many of these artists, such as Sasha Blonder, willingly painted the Shabbat bread, challah, Shabbat candlesticks, and other objects of everyday Jewish life.

Strangely enough, a sharp confrontation between generations is not documented. This was in contrast to the proletarian Jewish artists, who clashed with their parents quite strongly, as the Soviet perspective demanded not the gradual creation of some new art but the destruction of everything that came before them. It offered them atheism, rather than a new religion, instead of their traditional religion. That was one of the reasons why I did not want to deal with Soviet art. I found it all too unpleasant.

Everything happened very naturally in Lviv. There was one constructive moment; one constructive activity replaced another; and the transition occurred more or less seamlessly. There was no need to destroy anything, such as synagogues, ideals, or something like that. This was done later by the Soviets and the fascists, i.e., the invaders.

The rise of secular Jewish artists in the early 20th century

Yelyzaveta Tsarehradska: Did this 1900–1939 period serve as a foundation for other trends? Were there any artists that emerged from this school later? Who were the central figures?

Bohdana Pinchevska: You forget about the Holocaust. But it was quite simple in terms of names. In the 19th century, roughly speaking, the Gottlieb family (Maurycy Gottlieb and later his brother Leopold) represented the Ukrainian side. On the Polish side, there was Samuel Hirszenberg, an outstanding painter who depicted Jewish life and was afraid of it, keeping a lot of Jewish-themed paintings at home.

In the 20th century, before the beginning of the First World War, Wilhelm Wachtel and Maurycy "Ephraim Moses" Lilien were the key figures. These two names are enough to understand where the Jewish community was headed. They were leaders in the modern sense of the word. Lilien is still compared to Aubrey Beardsley, although he did not paint a single erotic picture in his life. Lilien produced graphics and was not inferior to Beardsley in the sophistication of modern drawing. Wachtel was more of a realist, but he wanted to absorb everything at once, turn it into creative output, and proclaim the joy of existence in this world for everything that surrounds him and himself as a Jewish artist.

Then, during the First World War, artists of the next generation ran to attend lectures under shelling in Lviv. Those times, from 1914 to 1918, were miserable, anxious, and restless. Then came the interwar period, my favorite, and a very interesting situation arose. The next generation of artists grew up, and they had already read, for example, Holubets' very professionally and thoroughly written analytical articles about exhibitions. Contributors to the periodicals of that time included teachers and professors from the Lviv Polytechnic, professional columnists, art critics, and cultural figures. Polemics erupted on the pages of a Polish-language newspaper of Jewish orientation.

The artists of that time simply continued their line and their vision of modernity. It boiled down to two steps: studying for a while at an academy of fine arts in Warsaw or Kraków and then going to Paris, for example. In fact, this is how the famous Artes group emerged. So, Jewish artists simply studied together. They lived and spent time together as friends here in Lviv: Margit Sielska-Reich, Ludwik Lille, and all the others. Later, they studied in different cities in Poland, after which some moved to Paris and studied in various academies there for a long time. In the end, after a long journey, they studied under Fernand Léger.

They returned to Lviv with an extensive collection of Jewish art, polished and interpreted by the European art of that time. They wanted to continue working in that style at home and were perfectly successful in doing so, even though some exhibits were considered outrageous at the time. For example, one of Otto Hahn's paintings was simply removed from the exhibition because, according to visitors, he drew a horse from the wrong angle, and too much was visible. The police literally came and removed the painting from the exhibition. A scandal. But that was not the main thing. Those artists were not after scandals. Instead, they were developing the concept of soft surrealism.

It was a known fact that half of this group of artists, the Kraków group, were Jews. But this was of little concern to anyone. If their paintings happened to include any challah or Shabbat candlesticks at all, they were ruthlessly stylized. However, if some influences were conspicuous, critics, of course, wrote about it in newspapers.

These artists created what was, at the time, a modern method of rallying Jewish artists around an idea that was 100 percent secular. Perhaps educated people did not care much about your religion or ethnic origin, so it was unfashionable to ask these questions in a polite society back then. What mattered was what a person was doing, but there are few recollections about this.

This program is created with the support of Ukrainian Jewish Encounter (UJE), a Canadian charitable non-profit organization.

Originally appeared in Ukrainian (Hromadske Radio podcast) here.

This transcript has been edited for length and clarity.

Translated from the Ukrainian by Vasyl Starko.

NOTE: UJE does not necessarily endorse opinions expressed in articles and other materials published on its website and social media pages. Such materials are posted to promote discussion related to Ukrainian-Jewish interactions and relations. The website and social media pages will be places of information that reflect varied viewpoints.