Ukrainian forced laborers in Nazi Germany: recruitment, forced labor, and repatriation

The following article about Ukrainian forced laborers (male and female) in Nazi Germany during the Second World War focuses on their recruitment and labor exploitation, their return home, and Soviet filtration measures. The compensation payments that the Ostarbeiter were able to obtain in the 1990s and 2000s are also discussed.

A cuckoo flew off, alighted on a red viburnum,

A mother weeps in Ukraine, her daughter's in a foreign land.

Alighted on a red viburnum and began to koo-kooo,

The mother came out to take water, began to plead:

Little cuckoo, I beg you, fly to the foreign land

And bring me news of my child.

Where she goes, with whom she speaks,

Does she remember her dear mother? Is she very homesick?

Tell her, little cuckoo, that I am worrying here,

When melancholy creeps into my heart, I look at a photo.

As soon as I look at the photo, I am awash in tears,

Because my daughter is far away, cannot be seen from here.

And I don't know if I will ever see her again,

Because 3,000 kilometers — that's far.

Fly, then, fly, little cuckoo, to my daughter,

Tell me about her, how she lives and what she is doing.

And bring me news from the distant land,

Fly, fly, little cuckoo, I beg you.

(These composed songs are based accurately on our life with our brothers and sisters, 23 April 1943. MS [1]).

Poems set to the melody of the folk song "A Cuckoo Flew" were recorded by a resident of the village of Moisyntsi in Poltava oblast who was a forced laborer in Nazi Germany during the Second World War. Symbolically, this song is being evoked today, during Russia's aggressive war against Ukraine, and has been covered by Alyona-Alyona and Jerry Heil. To this day, thousands of similar examples of folklore — songs, poems, and proverbs — have preserved pictures of life under German slavery, raw emotions and experiences, and longing for home and close family. They were recorded in notebooks; people retold and recopied them for each other in letters and sent them throughout the territory of the Third Reich, always adding the parting phrase, "I hope that you will return soon to our Ukraine." But after the war, after returning home to the Soviet Union, these people were required to keep silent about their experience of forced labor because they had "worked for the enemy," and for this, they were often called "traitors of the Fatherland."

During the Second World War, approximately 13.5 million men, women, and children from 26 European countries worked on the territory of Nazi Germany, its allies, and Nazi-occupied territories. [2] Of them, over 4.5 million were prisoners of war, and 8.5 million were civilians and concentration camp prisoners. [3] According to the German historian Ulrich Herbert, the Nazi "exploitation of foreigners" in 1939–1945 was the most extensive mass use of foreigners in a state's economy since the time of slavery. [4] Residents of occupied Soviet territories constituted the largest group of forced laborers. In late September 1944, 7.9 million foreign civilians and POWs worked in the German economy, nearly 2.8 million of whom were brought from the USSR. [5]. More than half of these laborers were brought from the territory of present-day Ukraine. [6] During the German occupation, practically every Ukrainian family experienced the calamity of labor deportations. Forced labor in Nazi Germany and the Soviet postwar policy of repatriation had a tragic impact on the lives of millions of Ukrainians.

From agitation to forcible deportation

The predominant majority of Ukrainian citizens were brought under duress to the Third Reich from occupied Ukrainian territory in 1942–1944. However, the first Ukrainians were pressed into forced labor in Germany as early as the summer of 1939. These were inhabitants of Carpatho-Ukraine who had been brought to Austria to perform forced labor. [7] In early September 1939, the next batch to be sent to the Third Reich were Ukrainians — Polish citizens — who, as members of the Polish army, had been taken prisoner by the Germans and whose status was eventually changed to civilian laborers. Archival documents also attest that starting in September 1940, Ukrainians were among the POWs and civilian laborers arriving to work in the Third Reich from France [8], which was a center of the interwar labor immigration, where resettlers from Poland and Eastern Galician came in search of work [9].

The first civilian laborers from the territory of present-day Ukraine began arriving in Germany in the summer of 1941. They were residents of regions that had become part of the District of Galicia. [10] At this very time, captured Red Army Soldiers, among whom were Ukrainians by nationality or place of birth, began arriving in so-called camps for Russians. In the Third Reich, former Soviet POWs also held the status of civilian laborers. When mass deportations of the population to Germany from occupied Soviet-occupied territories began in the spring of 1942, the first contingents of "recruits" were captured soldiers released as "Ukrainians."

The Nazi recruitment campaign in occupied Soviet territory was launched in the winter of 1942 with such large Ukrainian cities as Kharkiv, Kyiv, Stalino, and Dnipropetrovsk as primary targets. One feature of the first labor contingents was people's specialization according to occupation, with preference given to men with specialties like construction, metallurgy, mining, etc. They were mostly voluntary in nature. This system, which was introduced in 1942–1944 and based on promises, social pressure, and brutal terror, allowed the Nazis to ship out roughly over two million laborers from the territory of Ukraine (in its present borders) to the Third Reich. [11]

The population's resistance grew in direct proportion to the increasing demands connected with the deportation of a workforce from Ukraine. By the summer of 1942, recruitment in Ukraine's capital city was carried out exclusively through a "planned hunt for people," meaning that hundreds of city residents were detained during roundups on streets, at marketplaces, in movie theaters, and on beaches. [12] During this period, resistance also increased among residents of rural regions. Reports prepared by the Security Police and the SD state that the population of the general district of Kyiv, "even despite threats of confiscations of cattle and shootings […] did not comply with the directives of village elders and the German police." [13]

There were various possibilities for evading deportation: getting a job at a business or institution controlled by the occupation regime; obtaining a medical certificate stating that a given individual was unfit for work; and bribing a minor official, such as a policeman, village elder, building supervisor, or labor market official. In most cases, the population had to resort to a risky method of avoiding deportation: sabotage and escape. During a meeting of territorial commissioners (Gebietskommissars) to discuss workforce supply to Germany from the general region of Lutsk and Volyn, the German officials complained: "All are saving themselves by running away, and roundups are carried out everywhere like attacks. Young people already spend nights exclusively outside villages because this method of recruitment is already quite well known by now. The general tendency among the Ukrainian population: No one shows up voluntarily." The remark made by the Gebietskommissar of Horokhiv was more laconic: "In my area, the entire population is in the forests." [14]

Arrested workers fled from recruitment points and resettlement camps, en route to the railway station, and during transportation by railway. The following verse appeared:

Hello, Kyiv.

I ate up [the contents of] my bag,

I will get some sausage

And run home.

The scale of escapes during the transportation of recruited people is attested by data cited in a report written by the head of the bodyguard team assigned to train No. 32119, which was transporting 2,063 people from Kyiv to Bietigheim: "During the entire journey, 48 men and women, along with six sick individuals, disappeared" [15] — and this happened in circumstances where, after the first successful escape of a man and a woman after a few hours of travel, four innocent people were publicly shot.

Life in the shadow of "OST"

Transferred from different territories and in different ways, Ukrainians in the Third Reich had various legal statuses and lived and worked under varied conditions. For example, Ukrainians from France brought to work in German enterprises enjoyed the same rights and other benefits as French civilian laborers. Laborers from western Ukraine (District of Galicia) had the official status of "Ukrainians" as opposed to Polish workers. This status allowed them to move about freely without supervision within the boundaries of their populated area, and they did not have to wear identification badges on their outer clothing. They could correspond with their loved ones without restrictions and censorship, obtain assistance from social welfare organizations, and satisfy their spiritual needs.

All residents of Ukrainian territories who had lived in the USSR until 1939 had the status of Ostarbeiter "Eastern workers." German officials used this term (along with "Russian civilians" and "Soviet Russians") to denote multinational groups of civilian laborers (non-Germans) who had been deported from occupied territories of the Soviet Union, thus clearly distinguishing their social and legal status from that of other foreign laborers. Legislation pertaining to these Eastern workers changed over the course of the war. In late 1942, they were permitted to correspond with their families (two letters per month) and, in November 1943, to leave the camp with the administration's permission. Nutrition standards for Soviet laborers were aligned with those for other foreign laborers in late 1944. However, Eastern workers continued to be the most disenfranchised and oppressed category of foreigners in the Third Reich until the end of the war.

The odds of surviving depended to a significant degree on whether a laborer ended up in a state enterprise, where working and living conditions were the most arduous, or with a farmer in a village, where it was easier to obtain food. One-third of Ostarbeiter worked in agriculture, 45 percent in industry, 4 percent in mining, 4 percent on construction sites, and nearly 12 percent in the service sector. [16]

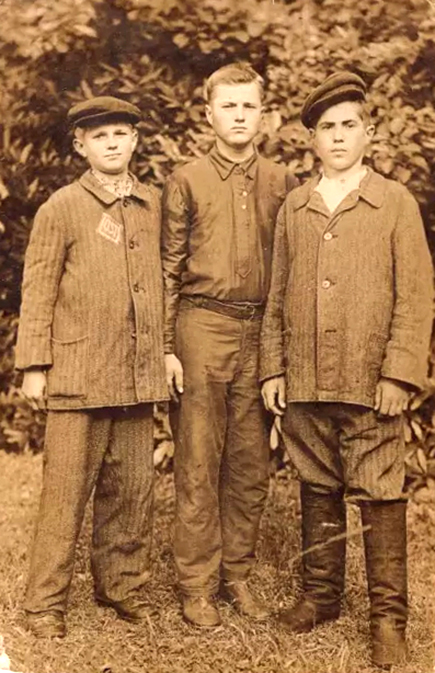

Foreign laborers were used not just in large-scale production; they could be found everywhere, from farms to small locksmith workshops. Large numbers of Ostarbeiter also worked for families living in German cities. The average age of forced laborers (both genders) from Soviet territories was between 20 and 24. One-third of the laborers were young people under the age of twenty. There is a considerable number of testimonies about large numbers of children aged 13 and 14 registered in worklists as "fit for work." [17]

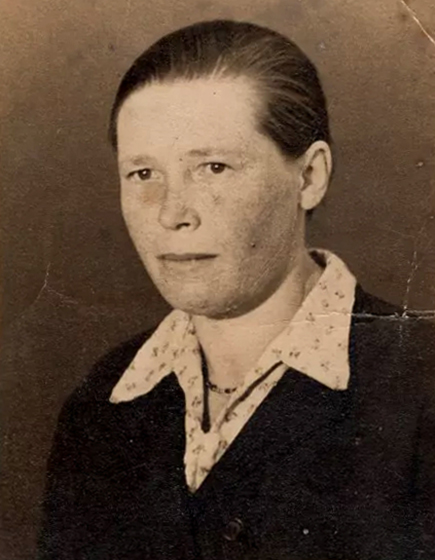

Women constituted the largest share of Ostarbeiter — 51 percent — a figure that reflected Nazi officials' racist policies targeting the workforce from the USSR. [18] Starting in 1943, young Ostarbeiter were most in demand as laborers in Nazi Germany's industrial enterprises. Their productivity was very high, and their earnings were low. Furthermore, they were not subject to the provisions of German social laws for women. German government agencies were least afraid of resistance on their part. Female laborers were helpless against sexual advances made by both German bosses and their fellow countrymen.

Social status

An Ostarbeiter camp was fenced in, often with barbed wire, and consisted of temporary housing barracks and a variety of auxiliary buildings: a kitchen, guard post, infirmary, dining room, bathhouse, toilets, etc. The wood barracks were mostly large one-story buildings divided into rooms. [20]

According to the nutrition standard introduced in December 1941, Ostarbeiter were supposed to be issued food totaling 2,540 calories a day. In April 1942, this standard was lowered to 2,070 calories and then raised again to 2,283 in early October. (The daily calorie intake was higher for laborers in the mining industry.) However, it was still the lowest of all other categories of foreigners. The nutrition standards for laborers from the West and the East were aligned only in the summer of 1944, and they were the same as those for the German population in October. [21] If we look at actual foods rather than the abstractions of calories and grams, the Ostarbeiter diet was very meager and monotonous for nearly the entire time these Eastern workers were in Germany. Poor living conditions, malnutrition, hard labor, the catastrophic state of sanitation and hygiene in the camps, and the spread of various parasites and pests meant that Ostarbeiter, compared to other foreigners, were the group with the highest percentage of injuries and fatalities resulting from infectious diseases and exhaustion.

Statistical data reveal that the average mortality rate among Ostarbeiter in 1943 was 1,210 deaths per month. [22] Most Ostarbeiter died of tuberculosis (23-40 percent of all deaths in 1943). The second most-cited cause of death was cardiovascular insufficiency and exhaustion (31 percent in March 1943). Between 6 and 12 percent of Ostarbeiter died of pleurisy and pneumonia, between 4 and 7 percent died due to industrial injuries, and between 2 and 4 percent died of typhus. [23]

The following fragment of a letter written by Kateryna Barabash aptly sums up the plight of the Ostarbeiter: "Halia, there is no life for anyone here. Just imagine a foreign land, poverty, and slavery."

Forms of resistance and types of punishment meted out to forced laborers

Nearly every sphere of activity in the lives of Ostarbeiter was closely controlled, mainly in the form of prohibitions and restrictions, as discussed earlier. Thus, even a bicycle ride taken by a Soviet laborer or a conversation with a German colleague smacked of a daring act that had to be punished. Deliberate violations of rules and regulations by Ostarbeiter were their most widespread model of behavior and resistance to their enslaved condition.

The most common form of protest among forced laborers was escape. German officials noted a large number of escapes during the transportation of civilian laborers from Ukraine. According to data compiled by the German historian Ulrich Herbert, nearly 45,000 foreign laborers in Germany escaped every month, approximately half a million every year, starting in 1943. More than half of them were Ostarbeiter. [24]

Nazi repression bodies established constant supervision and control over the "Eastern workers." It introduced a system of penalties for labor and political offenses, including imprisonment for several weeks in a corrective labor camp. People accused of more serious violations, such as escapes, theft, or sabotage, were punished by being sent to a concentration camp or, in some instances, executed.

How did the Ostarbeiter return home?

The history of forced laborers would not be complete without considering the Soviet state's policy toward those of its citizens who ended up in "enemy captivity."

In orders issued in 1942–1944 by Soviet judicial organs and the Prosecutor's Office, the very fact that a Soviet citizen had ended up in captivity or resided in the Third Reich was defined entirely legitimately as "treason against the fatherland," "complicity," and "an act of assisting the enemy." The relatives of these "criminals" were also to be prosecuted.

The change in the military and political situation in 1944 and the acute need for a labor force to rebuild the ruined country led to the introduction of certain correctives to the government's stance on the millions of Soviet citizens who had ended up abroad during the war (forced laborers and POWs). The key question was the need to organize the repatriation of the able-bodied population. On 11 November 1944, Pravda published an interview with General Filipp Golikov, the Soviet government's commissioner for repatriation, who declared that Soviet citizens "will not be prosecuted if they start honestly fulfilling their duty after returning to the Fatherland." [25]

But even those Soviet citizens permitted to return home had to undergo additional screening at the offices of the state security agencies, according to the results of which a so-called filtration case was opened for each person.

Despite the Soviet government's declaration of the rights and freedoms of the returnees [27], the reality was that the political status of these people differed little from that of criminal offenders. They had to undergo the same kinds of conversations with NKVD and NKGB officials; special cases were opened; they were obliged to register with the police and were banned from residing in capital cities. However, despite these prohibitions and restrictions, some former forced laborers managed to enjoy successful lives, obtain an education, hold high positions, and realize their creative plans. All they had to do was to keep quiet about the past. Valeria Komendatov (Vytvytska), a former Ostarbeiter, wrote about this in her memoirs: "For many years, I kept quiet. I kept quiet, afraid that everything would come out sooner or later. I was pursued by fear the entire time. At first, it seemed every policeman saw a thief in me. Later, I feared I would be identified at school and then at the institute as someone who had been in Germany, and I would not be permitted to complete my studies. This lasted quite a long time. All those years, I definitely felt guilt toward my friends, whom I could not even seek out, at least to thank them for what they had done for me and help them if they were having a difficult time. But I had to keep quiet and feel guilty without even knowing why."

For as long as the USSR existed, former forced laborers never founded their own civic organizations. Radical shifts took place only in the late 1980s, when the pressure of the totalitarian state eased, and the press began to publish articles about former Ostarbeiter and Nazi concentration camp prisoners. Civic organizations for victims of Nazi persecution were eventually founded. The registration of the legal and social status of former forced laborers was completed only after the Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine approved the law "On the Victims of Nazi Persecution" in 2000, which set out the legal, economic, and organizational principles concerning this category of citizens, guaranteeing them protection and commemoration.

Ukrainians in the Third Reich: How much did they receive?

A major role in accelerating the rehabilitation of Nazi victims was played by the humanitarian payments made by the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG) to former Ostarbeiter, as well as the public discussions that were launched in Ukrainian society in connection with them.

In 1999, 631,375 people in Ukraine received the first compensation payments, totaling 377,407,000 German marks.

In September 2000, under enormous international pressure, the foundation Remembrance, Responsibility, and Future was created in the FRG. Its mission was to make just financial compensations to former forced laborers. By June 2007, the foundation, financed by the German government and industrial organizations, paid out 4.37 billion euros to 1.6 billion people in more than a hundred countries. [28] In Ukraine, the foundation Mutual Understanding and Reconciliation made payments totaling 867 million euros to 471,000 claimants, including former Ostarbeiter and their heirs. [29]

Most Ukrainian recipients were women between 78 and 82 years old at the time of the payments (2002). This may be explained by the significantly shorter life span of men in Ukraine and by the fact that primarily young women were affected by the National Socialist policy of deportation.

In addition to the important process of issuing funds from the FRG, the German foundation Memory, Responsibility, and Future has continued to implement various humanitarian projects, providing support to former victims of Nazism in Ukraine and preserving their memory. The foundation has financed approximately 700 projects in various European countries, including Ukraine, since 2003s.

After Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the foundation's 42 projects provided Ukrainian civic organizations with urgent humanitarian assistance valued at 1.174 million euros (according to the information cited on the foundation's Facebook page). In March 2022, thousands of former forced laborers and concentration camp prisoners over the age of ninety received a small amount of urgent assistance in the form of medicines, food, and basic necessities.

Former victims of Nazism in Ukraine continue to receive aid from other German civic organizations, such as the Maximilian Kolbe Foundation; KONTAKTE-КОНТАКТЫ, the German Association for Contacts with Countries of the Former Soviet Union; memorials erected at former Nazi concentration camps; and thousands of concerned citizens. The recently founded civic association Aid Network for Survivors of Nazi Persecution in Ukraine has begun to provide assistance to former Nazi victims, mainly those in Ukraine's front-line regions.

These funds are not just material assistance to former Nazi victims and their relatives. They also represent crucial emotional support and are evidence that these people are not left alone during this difficult wartime period.

The photographs featured in this article are from the author's personal archive and the archives of the Pislia Tyshi (After Silence) NGO.

This text was created as part of the project “While Staying in Germany,” implemented by the Pislia Tyshi NGO with the support of Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung and funded by the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development.

References and notes

- TsDAHO Ukraїny (Central State Archives of Civic Organizations of Ukraine), f. 166, op. 3, spr. 111, fol. 5, zv.– 6.

- Mark Spoerer, Zwangsarbeit unter dem Hakenkreuz: Ausländische Zivilarbeiter, Kriegsgefangene und Häftlinge im Deutsche Reich und im besetzten Europa 1939–1945 (Stuttgart; Munich: Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt [DVA], 2001), p. 253.

- Ibid., pp. 221–22.

- Ulrich Herbert, Fremdarbeiter: Politik und Praxis des "Ausländer-Einsatzes" in der Kriegswirtschaft des Dritten Reiches (Bonn: Dietz, 1999), p. 7.

- Ulrich Herbert, ed., Europa und der "Reichseinsatz": ausländische Zivilarbeiter, Kriegsgefangene und KZ-Häftlinge in Deutschland 1938–1945 (Essen: Klartext-Verlag, 1991), p. 8.

- For detailed discussion of the problems of calculating the number of forced laborers from Ukraine in the Third Reich, see https://www.istpravda.com.ua/research/2012/05/8/84523.

- The memoirs of V. M. Lendel and O. M. Khymych were published in Pam'iat ′ zarady maibutn′oho: Spohady (Kyiv, 2001), pp. 285, 412. For detailed discussion, see https://www.istpravda.com.ua/research/2012/05/8/84523.

- TsDAVO Ukraїny (Central State Archives of Supreme Bodies of Power and Government of Ukraine), f. 3676, op. 4, spr. 127 (Questionnaires for persons born in Ukraine who worked in Germany in 1943–1945 and received work record books on the labor market in the city of Brandenburg) (Russian-language document).

- S. Kacharaba, Trudova emihratsiia iz Zakhidnoї Ukraїny u Frantsiiu (1919–1939 rr.), in Halychyna: Naukovyi і kul′turno-prosvitnii kraieznavchyi chasopys Prykarpats′koho universytetu imeni Vasylia Stefanyka, vyp. 8 (Ivano-Frankivsk, 2002), pp. 95–107.

- L′vivs′ki visti, 8 November 1941.

- For detailed discussion of the number of forced laborers from Ukraine in the Third Reich, see https://www.istpravda.com.ua/research/2012/05/8/84523.

- TsDAVO Ukraїny, f. 3676, op. 4, spr. 476, ark. 260 (Report of the KdS Kiew for 15 September 1942).

- TsDAVO Ukraїny, f. 3676, op. 4, spr. 475, ark. 208 (Report of the KdS Kiev for June 1942).

- TsDAHO Ukraїny, f. 57, op. 4, spr. 212, ark. 17–18.

- TsDAVO Ukraїny, f. 3206, op. 2, spr. 185, ark. 7.

- Spoerer, Zwangsarbeit.

- Ibid.

- Women accounted for roughly 33 percent of all civilian, foreign laborers in the Third Reich (as of August 1944 р.). Nearly 87 percent of female laborers were brought from Eastern Europe. See Herbert, Fremdarbeiter, pp. 315–16.

- Herbert, ed., Europa und der "Reichseinsatz," p. 12.

- TsDAVO Ukraїny, f. 3676, op. 4, spr. 311.

- Herbert, Fremdarbeiter, p. 199; Spoerer, Zwangsarbeit, pp. 125–26; P. Polian, Zhertvy dvukh diktatur: Zhizn′, trud, unizheniia i smert′ sovetskikh voennoplennykh i ostarbaiterov na chuzhbine i na rodine, 2d rev. and exp. ed. (Moscow: ROSSPEN, 2002), p. 250.

- Polian, Zhertvy dvukh diktatur, p. 258.

- Ibid., p. 257.

- Herbert, Fremdarbeiter, p. 360.

- For detailed discussion of the legal status and screening of former prisoners of war and civilians in the USSR, see Tetiana Pastushenko,"V'їzd repatriantiv do Kyieva zaboroneno": Povoienne zhyttia kolyshnikh ostarbaiteriv ta viis′kovopolonenykh v Ukraїni (Kyiv, 2011), http://resource.history.org.ua/item/0007068.

- V. I. Zemskov, Repatriatsiia peremeshchennykh sovetskikh grazhdan, in Voina i obshchestvo, 1941–1945: V 2-kh kn. (Moscow, 2004), 2: 342; Polian, Zhertvy dvukh diktatur, p. 529.

- Between 1944 and 1948, the Soviet government passed 67 resolutions on a variety of issues relating to the legal and social status of repatriated individuals. See Serhii Hal′chak, Na uzbichchi suspil′stva: Dolia ukraїns′kykh "ostarbaiteriv" (Podillia, 1942– 2007 rr.) (Vinnytsia: Merk′iuri-Podillia, 2009), p. 618.

- "Gemeinsame Verantwortung und moralische Pflicht": Abschlussbericht zu den Auszahlungsprogrammen der Stiftung "Erinnerung, Verantwortung und Zukunft," ed. Michael Jansen and Günter Saathoff (Göttingen: Wallstein, 2007).

- For more details, see the statement issued by the Ukrainian national foundation Mutual Understanding and Reconciliation, https://shostkamuseum.com.ua/arhiv/dokumenti/gumanitarni-viplati-uryadu-frn-kolishnim-zhertvam-natsizmu.

Tetiana Pastushenko holds the Candidate of Historical Sciences degree and is a Senior Fellow of the Institute of Ukrainian History, the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine. She currently holds the Philipp Schwartz Fellowship at the Ruprecht Karl University of Heidelberg, Germany. She is a graduate of Taras Shevchenko Kyiv National University. From 1989 to 2004, she worked at the National Museum of the History of the 1941–1945 Great Patriotic War (now the National Museum of the History of Ukraine during the Second World War). In 2007, she defended her doctoral dissertation, "Ostarbeiter from Ukraine: Recruitment, Forced Labor, Repatriation (A Historical and Social Analysis Based on Materials Pertaining to Kyiv Oblast)." She has worked in the Department of the History of Ukraine during the Second World War since 2004. Her primary scholarly interests include the Nazi occupation regime, the forced labor of foreigners in the Third Reich, concentration camp prisoners, Soviet POWs, Stalinist repressions during the war, the culture of memory about the Second World War, and oral history. She is the author of many scholarly and popular science publications and a curator of exhibitions and Internet sites.

Tetiana Pastushenko holds the Candidate of Historical Sciences degree and is a Senior Fellow of the Institute of Ukrainian History, the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine. She currently holds the Philipp Schwartz Fellowship at the Ruprecht Karl University of Heidelberg, Germany. She is a graduate of Taras Shevchenko Kyiv National University. From 1989 to 2004, she worked at the National Museum of the History of the 1941–1945 Great Patriotic War (now the National Museum of the History of Ukraine during the Second World War). In 2007, she defended her doctoral dissertation, "Ostarbeiter from Ukraine: Recruitment, Forced Labor, Repatriation (A Historical and Social Analysis Based on Materials Pertaining to Kyiv Oblast)." She has worked in the Department of the History of Ukraine during the Second World War since 2004. Her primary scholarly interests include the Nazi occupation regime, the forced labor of foreigners in the Third Reich, concentration camp prisoners, Soviet POWs, Stalinist repressions during the war, the culture of memory about the Second World War, and oral history. She is the author of many scholarly and popular science publications and a curator of exhibitions and Internet sites.

Originally appeared in Ukrainian @Ukraina Moderna.

This article was published as part of a project supported by the Canadian non-profit charitable organization Ukrainian Jewish Encounter.

Translated from the Ukrainian by Marta D. Olynyk.

NOTE: UJE does not necessarily endorse opinions expressed in articles and other materials published on its website and social media pages. Such materials are posted to promote discussion related to Ukrainian-Jewish interactions and relations. The website and social media pages will be places of information that reflect varied viewpoints.