Vasyl Makhno's New Poetry Collection Jerusalem Poems

Vasyl Makhno presents, and reads from, his new collection Jerusalem Poems on the program Encounters.

Iryna Slavinska: You are listening to Hromadske Radio and I’m Iryna Slavinska with the program Encounters. Today you will hear an interview with the poet Vasyl Makhno. Our conversation took place at the Lviv Book Forum, and we discuss his recently published collection Jerusalem Poems.

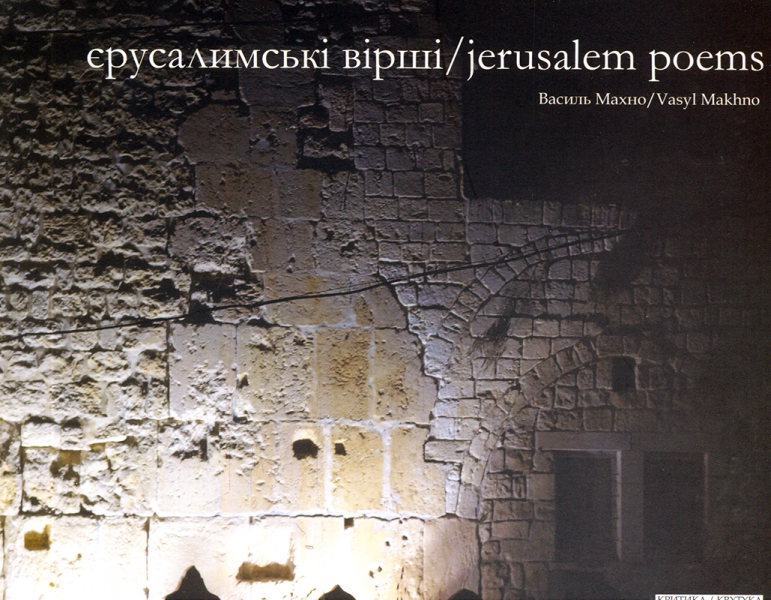

Vasyl Makhno: This book has quite an extensive preface written by Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern and the smallest of my poem series called "The Crickets and the Doves," which consists of seven poems, which is, in fact my Jerusalem cycle of poems. The book is bilingual, i.e. Ukrainian-English. This is its main body. In addition, it is lavishly illustrated with photographs by Matvey Vaisberg and Volodymyr Davydenko. It is a rather deluxe artistic edition, or art book, as it is called today.

Iryna Slavinska: Petrovsky-Shtern's preface has a very interesting thesis that Vasyl Makhno as a poet assumes the responsibility to speak for those minorities that often happen to be invisible, if judged from the point of view of ethnic Ukrainian-centered Ukrainian literature and culture. I think, this context would be quite a good start for our conversation about this collection. Is this context relevant at all for Vasyl Makhno the poet?

Vasyl Makhno: Somehow it happened that this frontier I have dwelt on since I was a child, and to this day (its location has changed however), had somehow manifested itself recently. Already living in America, I started looking at these Eastern European borderland towns, Ukrainian frontier zones that were inhabited by different ethnic groups and different cultures. It was a truly multicultural experience.

I'm not saying that everything was serene during those centuries of coexistence. But anyway, these ethnic groups and cultures influenced one another. When I published my previous book, Rover, I have really plunged into this. Because of my childhood memories, I was willing to reconstruct that lost world. I was acquainted with it, because the lost world means first of all people, who, during Austrian, or Polish rule, picked up these languages or their fragments: German, Polish, Yiddish. Those pieces lingered in my memory and in my vocabulary when I was a child, because those people used those words. So my principal idea is to recreate the lost world, which is very private and very important to me.

Iryna Slavinska: Why would one want to reconstruct it?

Vasyl Makhno: For the sake of memory. And in order to experience it again. I believe that memory and history are very important components for the modern world.

Iryna Slavinska: At all time, when it comes to memory, we should rather remember that memory is a construction. It doesn't appear on its own, is not something natural. It is constructed by humans, in a private way for each person, through recollecting some individual issues. Also, constructing memory is certainly influenced by greater narratives: the government, textbooks, and curricula, whatever. Speaking of one's private memory, this "lost world," and the memory of this world, if it exists at all in modern Ukraine – how much do they have in common?

Vasyl Makhno: This question is very interesting, exactly because that kind of balance merely does not exist there. Maybe the reason why I did it will provide an answer. I realized that many things were simply wiped out and left behind due to various reasons. Perhaps, for me it was important to capture it all in a poetic text or prose. I think that contemporary Ukrainian society is too excited about some quite modern social issues, which is obvious and normal. However, this society, these people, these contemporaries of ours, should just know as well what land they live on, and what was there before, because this will provide a component for one's self reconstruction. I believe this is very important.

Iryna Slavinska: If we continue with this idea, I think it's true that in many fields there is a longing for this maximum homogenization, to a Ukraine with one language, one nation... and this sequence of synonyms may be continued, and it will be quite frightful, of course. I think that the revival of these, by Ihor Pomerantsev's definition, "drafts"—national, linguistic, coursing through the country—can really add more colors and more languages. How difficult is this work, how eccentric does it seem—to revive forgotten languages, faces, and peoples?

Vasyl Makhno: On one hand, it's not that eccentric, but sometimes it just feels like running idle, in my opinion. You can't always predict how it will be properly perceived. Modern Ukrainian society thinks in contemporary and somewhat future terms, it is longing for ephemeral happiness. Many people see it in the abolition of visas and the accession to Europe, which is not bad at all. It's quite great.

But the writer who works with words knows that a word has three dimensions: past, present, and future. These past things, these drafts of history, this echo, it's important to hear them and to feel that you are living in three-dimensional time. It's characteristic for many literatures, especially in the Slavic world, Polish or Slovak, that these border areas and territories have their own extollers. For example, Andrzej Stasiuk in Poland. This is not something specific only for Ukrainian literature. For Europe, which has been long divided with borders, and which has always experienced a lot of conflicts due to that, exploring these topics is very important in order to answer specific questions that modernity poses us.

Iryna Slavinska: What are these questions? In what way can exploring and reconstructing the world of Jewish shetls in Ukraine, for example, be helpful for modern Ukraine? What will it answer?

Vasyl Makhno: Perhaps, the first question is the awareness that someone lived next to us. These people had their own language, culture, and, in one way or another, we interacted with them through various relations. Exploring other cultures and ethnic groups is only enriching. On the other hand, the tragic events that occurred between Ukrainians, Jews, and Poles, also constitute lessons of history that give us a clue what to do today. These issues that would seem erased, gone, outdated, obliterated, because those people who lived at that time are gone, emerge at this particular time. And now there's this dilemma between the past and the present. I'm not saying that raising these issues of boundaries or multicultural life will answer all the questions, since modernity has other challenges. But I am convinced that it will help us understand something.

Iryna Slavinska: Here it maybe makes sense to mention a much-discussed case, particularly in 2016. This is the exacerbated wave of discussions around the Volyn tragedy and perhaps this is a perfect example of what you mean. The memory of the minorities that could be living on the Ukrainian territories, an unworked memory, a scarcely elaborated narrative about this memory, erupts already in forms of political conflict and political action. Perhaps you have an opinion or a reflection on what is happening between Ukraine and Poland? Of course, I'm not talking only about the courtesies exchange between the [Polish legislature—Ed.] Sejm and the [Ukrainian parliament—Ed.] Verkhovna Rada, but about this situation in general, as a certain structure.

Vasyl Makhno: I've been to Poland thousands of times, in different regions, and talked with many people. In 1945, my family on my father's side was forcibly resettled from Poland, from the village of Dubno, near Leżajsk. Which means, I share traumatic memory even on the family level.

Of course, the issue of Volyn is an eternal theme for Poles. Whoever I talked to in Poland, always mentioned this subject. Over the past ten years, it wasn't as actualized as today. Which means, it was remembered. Yes, there would always be the Polish rightists who would always play this particular card. And this issue came out again at the present moment, not at the best time for Ukraine. We've got war, the ATO [Anti-terrorist operation—Ed.], and internal problems. Poland has always been our ally, since the independence, at least the official Poland has always supported it. And then, all of a sudden, there appears this situation that doesn't favor Ukrainian-Polish relations and likely doesn't favor Ukraine either, in this current complex situation.

Iryna Slavinska: Where one can see Polish rightists who play up this situation, one can also see Ukrainian rightists who are doing quite the same, on their side, symmetrically, exploit the theme of the victims and the executioners.

Vasyl Makhno: I think that this ping-pong between certain political circles in Poland and Ukraine has some purpose. It is more or less hidden, and it may be a major political game where we don't know who the puppeteers are.

Iryna Slavinska: Let's return to your collection. Tell us about working on it.

Vasyl Makhno: In 2015, I first visited Israel and Jerusalem, and traveled, in fact, throughout the entire north of Israel. This trip was sponsored by a Ukrainian Jewish Encounter scholarship, and I wasn't imposed with any obligations. When I returned to New York, I started writing those poems. I've understood one thing I wanted to convey by them. I didn't want this to be reporting poetry. However, on the other hand, I didn't want it to be religious poetry. I was willing to find some worldview and philosophical balance if there is such a definition. That is why I decided that a cycle would open and end with some psalm, and in the middle there would be various things that moved me to write, or caught my eye, or lingered in my memory.

Why does the whole collection refer to Jerusalem? Because it was there where I spent the most time. It is the heart of the Holy Land. I didn't want to call the collection "Poems from Jerusalem." However, I wanted Jerusalem to be featured in the title. This is the whole concept, so to say.

Iryna Slavinska: This seems to need some comment, as the Psalm is a complicated genre.

Vasyl Makhno: I'm quite sure that David's Psalms and those I wrote here, are totally different. The very definition of "psalm" was important to me because the genre itself refers you to the Holy Scriptures, to this structure. Definitely, there's something I've modernized, some experiences I've expressed in a more contemporary way, but it was crucial for me to emphasize that two of the poems belong to this genre, because the others have a different connotation.

Iryna Slavinska: Perhaps it makes sense to comment on why the psalm, why this particular genre, was so important to frame the opening and the ending of the collection.

Vasyl Makhno: I wouldn't like it to be perceived solely as religious poetry. However, I couldn't withdraw from the tradition of the Holy Scriptures and those nuances, too. When you get into the space of Jerusalem, especially into the Old City, when you are walking and you are told: this the Garden of Gethsemane, this is Zechariah's tomb... Everything that you've only imagined during your entire life instantly condenses into a very small space. And you realize that this is actually a really small spot, where all those events happened. And now you are making this way on your own for several hours. It is an absolutely uncanny feeling. This is not a feeling of a religious person, but a feeling of a person who read the Holy Scriptures, musing on Christian and Jewish texts, history, legends, and myths. This can't but have an effect.

Iryna Slavinska: I'm recalling a space, which first comes to my mind when I think about Jerusalem. This is Yad Vashem. This is not one of those ancient Biblical places, but the space devoted to modern history, the experience of the Holocaust. Did you have a chance to visit this place?

Vasyl Makhno: No, I haven't been there. We had a thoroughly planned schedule. First, there was a public reading at the [Hebrew] University, then we travelled to the North. One of the places that we visited was the city of Safed—one of the four holy sites for Jews. There I spent a Shabbat together with the Hasidim, Orthodox experts of Judaism. The schedule was really tight. We went to other cities such as Haifa and Acre. There were other meetings in Jerusalem. Also, it was important for me to visit the museum of my landsman—Shmuel Y. Agnon.

Iryna Slavinska: Please tell us about this experience. Agnon is returning to Ukraine as an author, in particular, thanks to the Agnon Center in Buchach.

Vasyl Makhno: I'll start from afar. This was in the 1990s. Yuri Andrukhovych called me from Ivano-Frankivsk and said Agnon's daughter came to visit, along with French television. He asked me to meet her and take her on a tour. So I met her and her husband. It was, perhaps, then when I ever learned Shmuel Y. Agnon existed. It seems to me that back then there was only one Russian translation of his texts, within the Nobel Prize Winners series. Thus began my encounter with Agnon. During my visit in Israel, I tried to find out something about Agnon's museum and about his daughter. She was quite senile and was in a nursing home. Since so many years have passed, I made a decision not to see her. After coming back to New York, I learned that just a few days after my return she died. She must have been almost hundred years old.

Iryna Slavinska: That was the poet Vasyl Makhno talking about his book Jerusalem Poems. This has been Iryna Slavinska in the studio for the program Encounters, which is supported by the philanthropic fund Ukrainian Jewish Encounter. This is Hromadske Radio. Listen. Think.

This program is created with the support of the Canadian philanthropic fund Ukrainian Jewish Encounter.

Originally appeared in Ukrainian (podcast) here.