"We must see the Holodomor as one of many attempts to subjugate Ukraine since the reign of Peter I or even earlier" — Daria Mattingly

The following interview with the Holodomor researcher Daria Mattingly focuses on her view of the current state and prospects of Holodomor studies. Dr. Mattingly recounts a personal story that prompted her to study the Holodomor. In her analysis of the development of historiography, she pays special attention to the role of local people who implemented the Soviet government's policy of genocide. The question of commemorating the victims of the Holodomor was also discussed.

"I was raised by my grandmother, who survived the Holodomor"

Why and when did you become interested in the study of the Holodomor in 1932–33? Were there personal factors that prompted you to study this topic?

My interest in Holodomor studies developed over time. Growing up in Ukraine in the 1980s and 1990s, I could not avoid this history. Besides, I was partly raised by my grandmother, who had survived the Holodomor. So, I grew up in surroundings where these tragic events were often discussed. My family had a special reverence for food, and we were always told that nothing should be left uneaten on our plates; not even crumbs of bread could be wasted. My family's recollections of the Holodomor were accompanied by stories about the extremely difficult survival strategies. My grandmother often recalled how her family decided not to butcher the cow for meat, as had been done by our neighbors, who ended up dying during the Holodomor. There was often talk of the family members who had survived and the ones who had not. What always fascinated me about these stories was how all this became a reality because I could not imagine the possibility of famine in Ukraine. My grandmother is no longer with us, or I would ask her many questions I posed to people in the villages as I carried out my oral history project. So, my position on scholarly Holodomor studies is very personal; these events are part of my own family history. That is why I decided to study this topic more systematically in the context of conversations that had taken place during my childhood.

Researchers have long claimed that the Holodomor is an under-researched topic. What is the current state of research? Which historiographic stages of Holodomor studies would you single out? What role do foreign historians play, and to what degree are Holodomor studies developing in Ukraine?

Here, of course, it is impossible to avoid a comparison with the development of Holocaust studies. Rethinking academic studies requires temporal distance from a trauma like the Holodomor. Just like in the study of the Holocaust, the main focus in the history of the Holodomor was initially on preserving and recording memory. In the Ukrainian diaspora, activists recorded eyewitnesses' experiences during the genocide. However, the academic study of this history begins only in the 1980s, with the publication of research by James Mace and Robert Conquest. So, research on the Holodomor began overseas, partly within the Ukrainian diaspora. In Ukraine, the advancement of Holodomor studies coincides with the introduction of glasnost in the USSR in the 1980s and especially the period following Ukraine's independence. In the beginning, data was collected, and archival documents were published. Researchers then focused on studying demographic losses during the Holodomor and discussed the genocide interpretation and ways to commemorate it. The social history of the Holodomor gradually emerged and developed. Researchers studied the genocide from various perspectives: gender, children's history, and the history of other social groups. That is, they looked at how their experience of genocidal violence was driven by their affiliation with certain communities. At this stage, a large number of studies were devoted to establishing the number of victims. But this is more the subject area of demographers than historians, who, admittedly, have offered their own estimations of demographic losses.

Thus, the first period in the emergence of Holodomor studies was in the diaspora. The publication of archival documents began in the 1990s. After 2015, we see a narrower specialization of Holodomor studies and a deeper theoretical understanding of the genocide. The publication of a collection of articles entitled Contextualizing the Holodomor: The Impact of Thirty Years of Ukrainian Famine Studies [1] provided a powerful impetus to this. Social and cultural history, that is, research on how the Holodomor has been represented in literature, drama, and poetry or on various experiences of the Holodomor, has also developed robustly. Some researchers working in these highly specialized fields are Volodymyr Dibrova, John Vsetecka, Kristina Hook, Oksana Kis, Oksana Vynnyk, Iryna Skubii, and Karolina Koziura. Today, a constellation of new, young researchers, both abroad and in Ukraine, are studying the history of the Holodomor. So, there are grounds for optimism regarding the further development of Holodomor studies.

"Since the Cold War era, researchers outside Ukraine are still grouped around two schools of historiography: revisionist and orthodox"

How does current historiography explain the causes and the beginning of the Holodomor?

That depends on which historiography we are talking about. For example, since the Cold War era, researchers outside Ukraine have been grouped around two schools of historiography: revisionist and orthodox (the latter also known as the totalitarian school of historiography). They have differing interpretations of the Soviet leadership's intentions during the Holodomor of 1932–1933. Despite the publication of various sources, including archival documents, correspondence, or telegrams between Stalin and his circle, which unequivocally reveal the genocidal intentions of the top leadership of the USSR (Stalin, Molotov, Kaganovich, and others), one still finds denials of the artificial character of the Holodomor in the writings of revisionist researchers. For example, Mark Тauger continues to insist that the "famine" was caused by natural conditions, such as drought. In other words, he uses the typical Soviet narrative to explain the causes and course of the Holodomor of 1932–1933, while Sheila Fitzpatrick claims that Stalin was not aware of the scale of the famine in Ukraine.

I belong to the orthodox school of historiography. As I see it, there is no doubt that the Holodomor was engineered. This point of view is shared by Аlex de Waal, a leading scholar on famines, who says that famines have never occurred by chance in modern history. Of course, droughts or pestilence have occurred, but in the modern era, political leaders have always had adequate instruments at their disposal to prevent mass starvation. In other words, the key responsibility for a famine falls on political figures. In 1921, the Soviet leadership appealed to the international community for help to prevent famine or to provide relief for its starving citizens, but that did not happen in 1932–1933. It did not halt grain exports and failed to redistribute existing resources; the Soviet government did not consider it necessary to save its citizens. A critical mass of historians agree that the Holodomor was caused by political factors, such as the desire to intensify control over Ukraine and suppress it during the period of collectivization. After all, we know that the greatest resistance to collectivization in the USSR was in Ukraine; that is, there were political reasons here to resort to a policy of genocide.

As for the start of the Holodomor, it is worthwhile mentioning that the historians Andrea Graziosi, Stanislav Kulchytsky, and others assert that there was a famine within the famine, meaning that collectivization sparked a famine that encompassed many regions of the Soviet Union. However, one must distinguish the famine within the famine — the Holodomor. During this period, the Soviet leadership introduced measures and political decisions that intensified the famine, claiming the lives of millions of people within a brief period of time. In other words, this could not have been organized without collectivization, but the introduction of "blacklists," the November 1932 meat procurements, the closure of Soviet Ukraine's borders, and other measures were elements of the policy of genocide. Analysis of Soviet leaders' correspondence reveals that they singled out Ukraine amidst the all-Soviet experience of collectivization and famine. Thus, arguments along the lines of "everyone was starving" are absurd and do not withstand scrutiny.

What role did the bureaucratic apparatus of the USSR play in engineering this crime? Which institutions and leaders bear the primary responsibility?

The USSR was a modern state, and therefore, the Holodomor was a modern genocide. If we look at the histories of the Holocaust and the Holodomor and at other totalitarian states' policies of genocide, they always rely on a bureaucratic apparatus. Regarding the Holodomor, the orders issued by the highest Soviet leadership came down to the republican leaders of the Ukrainian SSR, who in turn transmitted them to raions and villages. Thus, we are talking about a strict vertical of state power, which was a dual one that included the vertical of state government agencies and the Communist Party. Republican, oblast, and raion committees played an important role in the structure of the party organization at the level of the grassroots implementation of the policy of genocide. The instigators of the crime were clearly the highest Soviet and Communist Party leadership: Stalin, Kaganovich, and Molotov. In 2010, a trial took place in Ukraine in case no. 475. All the key perpetrators of the Holodomor were indicted in court, found guilty of engineering the Holodomor, and sentenced posthumously.

In July 1932, grain procurement plans were issued from the highest level and confirmed at the 3rd Conference of the Central Committee of the Communist Party (Bolshevik) of Ukraine, which took place in Kharkiv on 6–9 July 1932. The plans were slated for implementation by the republican leadership and representatives of local government bodies. The grain procurement plans developed by the highest leadership of the USSR immediately sparked dissatisfaction and objections in the Ukrainian SSR. People understood that their implementation would lead to extraordinary losses. However, all resistance petered out within six months or so, not least of all because of the show trials of local cadres who refused to execute these orders.

Thus, raion party and executive committees, village administrations, and party centers played a significant role in perpetuating the Holodomor. There were quite a few communists among them, but not everyone who implemented the policy of genocide belonged to the Communist Party. It is worth noting the vital role played in these processes by the militia, especially the security service — the OGPU (Joint State Political Directorate) — which closely scrutinized the implementation of all orders and drew up memoranda to monitor the course of the genocidal process.

"The greater part of the population, even in cities, was compromised"

Were there local perpetrators/people involved in the genocide — Ukrainians, for example, and others? How many were there? What was their ethnic breakdown, and what role did they play?

Yes, other institutions — teachers, for example — also participated in the Holodomor. The People's Commissariat of Education was involved because teachers were the representatives of the state in the countryside and thus obliged to participate: to calculate how many eggs and how much milk and other foods were being seized from the peasants, to conduct searches, etc. Students and officials of justice departments, the army, and Interior Troops were also mobilized. Workers employed at Machine-Tractor Stations (MTSs), Komsomol and Pioneer activists, watchmen, and mobile patrollers who rode around fields were also mobilized. Over 20,000 young men and women, members of the Tsoaviakhim, the Society for Assistance to Defense, Aviation, and Chemical Construction, a paramilitary youth sports organization, were sent to guard fields and the 1933 harvest, at the precise time people went out to gather the grain. The Soviet leadership also mobilized urban residents to take part in the Holodomor. Workers of both sexes were dispatched from enterprises to the countryside, where they were ordered to confiscate grain. Thus, the majority of the population, even in cities, was compromised.

As for the ethnic breakdown of Holodomor perpetrators, I would say straight off that ethnic affiliation does not necessarily determine an individual's political orientation and national identification in the broader context. Our Ukrainian understanding of nationality or cultural affiliation is often dictated by ethnic background. Owing to this and other factors, the accusation that Jews were complicit in the Holodomor, as well as other antisemitic beliefs, appeared in the discourse about the genocide. First of all, these beliefs are based on the fact that a substantial number of people of Jewish background worked in the OGPU (known as the CHeKA at the dawn of the formation of the USSR) because their level of education was higher than that of people from other ethnic groups that populated the state. So, in certain cases, they moved up the career ladder to top positions in the hierarchy of the state security organs. But can these people be considered Jews in the national context? They were Soviet people, loyal to the USSR, and committed to the regime that facilitated their career growth. It is difficult to conclude that their ethnic origin somehow influenced their professional political activities. Such erroneous interpretations occasionally appear in belles-lettres, for example, in Mykhailo Stelmakh's novel Chotyry brody (Four Fords), in which the author explains the intentions of local perpetrators in a somewhat antisemitic manner by pointing out their Jewish background, or in Nataliia Doliak's novel Chorna doshka (Blacklist), in which the "oriental" appearance and exceptional sadism of the main perpetrator, Marko Milman, are emphasized. In fact, this tendency is undetectable in archival documents.

However, the Holodomor exacerbates the antisemitic beliefs of non-Jewish victims and eyewitnesses. This is connected in particular to the myth of Judeo-Communism. The sporadic presence of OGPU heads and employees with Jewish given names and surnames gives rise to a number of incorrect conclusions and generalizations. Since people legitimately associated the organization and implementation of the Holodomor with the communists, and communism was regarded here and there as a "Jewish regime," false conclusions about the collective guilt of an entire nation emerged in people's perceptions and the public discourse. In this context, of course, the Holodomor intensified antisemitism in part of the Ukrainian population. However, the fact remains that Jews, too, suffered in the genocide; like Ukrainians, they were both executioners and victims during the Holodomor. The Soviet regime caused the destruction of small Jewish towns known as shtetls. People who professed Judaism were also subjected to repressions, sometimes by people of Jewish background. In other words, everyone in rural areas suffered, apart from the perpetrators, during the Holodomor in Ukraine.

Importantly, Ukrainian Jews predominated in the OGPU in the early 1920s, which is discussed in research done by Yuri Shapoval and Vadym Zolotaryov. However, we see a more balanced representation of various ethnic groups in the ranks of the OGPU in the early 1930s. During this period, Ukrainians also served in the state security organs, and their share in them was proportional to the size of the Ukrainian population of the republic. The ethnic breakdown of perpetrators and organizers of the Holodomor proportionally represents the ethnic composition of the population of the Ukrainian SSR during this period. I conducted statistical research on the composition of raion party committees and found that they represented a demographic profile of Ukraine's population at the time. My research covered the southern, eastern, western, northern, and central oblasts of Ukraine — the key regions of the Ukrainian SSR within its boundaries at the time. I went on expeditions to various villages and worked on documents from villages in Donetsk, Kyiv, Odesa, and other oblasts. Interestingly, in some ethnic districts, like Stalindorf (Markhlevsk raion), or among German settlers in villages, most perpetrators were Germans, Poles, Ukrainians, or Jews.

"The Holodomor differed from other genocides in that the outcomes of these deadly actions did not appear right away"

You mentioned a certain period of habituation. Initially, various forms of resistance to the Holodomor policy were observed in the milieu of rank-and-file perpetrators, but they weakened over time. Can you provide more details?

Yes, approximately one-third of functionaries opposed the grain procurement plans of 1932–33 at the local leadership level. People knew what their actions and directives might lead to because no one could survive without food. But the Holodomor differed from other genocides in that the outcomes of these deadly actions did not appear right away; the horrific consequences began to emerge after a few months. This may have affected the dynamics behind the perpetrators' habituation to the ongoing policy of genocide.

It is also important to note that during this period, forcible modernization — which in and of itself devalued human life — took place in Ukraine. This was layered onto the context of the traditional society that existed in the Ukrainian countryside. One could observe there, as in any other premodern society, a certain habituation to the high mortality rate. For example, there was a high child mortality rate, which partially balanced out and perhaps even led to a high birth rate. A considerable number of women died during childbirth; people died during various epidemics. The Ukrainian rural world was thus accustomed to death, and this certainly accelerated the adaptation of rank-and-file local perpetrators of the Holodomor to the totalitarian regime's policies of repression and genocide.

Not everyone dared to resist. In the fall of 1932, after the completion of the grain procurements, the Soviet authorities held a series of show trials directed at people who had "sabotaged" the grain procurements. Around 27,000 low-level workers were arrested, and 16,000 of them were tried; only 0.6 percent of the convicted defendants were shot. The public nature of these show trials sowed fear, leading citizens to think that objecting to orders was not worthwhile. If they were arrested, their families would lose their essential living resources: ration cards, rations, and other vitally important things during the Holodomor. This repressive instrument proved effective because most perpetrators had stopped resisting by the winter of 1932 and had not discarded their party membership cards, as they had done in August 1932, but simply carried out orders.

"In villages, everyone was involved in the genocide in some way"

How did the local population that did not suffer during the Holodomor, particularly urban residents, position itself during the genocide? In Holocaust studies, academic discussions have resulted in the rejection of the concept of "bystanders." Are these findings relevant for Holodomor studies?

Ten years ago, when I began studying this topic, I sought to apply the concept of "bystanders" to analyze the experience of various population groups in the countryside during the Holodomor. However, I concluded over time that it did not have sufficient analytical value for my research on the Holodomor because everyone in villages was ensnared in the genocide one way or another, both as victims and perpetrators. The same processes were at work in small towns. There was high mortality among workers in factories and plants that occupied the lowest rung of the food supply system, such as the shoe and porcelain factories in Berdychiv and Korosten, in Zhytomyr oblast. Workers there died of hunger right at their place of work, standing at their machines. If you happened to be a correspondent of a raion newspaper or a village correspondent (silkor), you were obliged to write memos denouncing neighbors and the local administration, and these actions had immediate repercussions. In other words, people who were not suffering from hunger themselves were often drawn into the process of this criminal policy. If someone was employed as a teacher, s/he was tasked with questioning pupils about where their parents were concealing grain or other foods. Even if you were a secretary of a village soviet, not to mention a member of the collective farm board or a village official, you were forced to become involved in the process in some way. If you were a watchman, you guarded grain and other foods so that people could not steal them and feed themselves. As a mobile patrol guard, you were obliged to prevent people from cutting ears of grain. And even if you were simply collecting dead bodies and transporting them to a cemetery, you were still part of the immense killing mechanism. It is important to note that the boundaries between victim and perpetrator were often blurred during the Holodomor. Depending on the circumstances, people could switch from a group of victims to a group of perpetrators and vice versa.

Tell us a bit about your Holodomor oral history project.

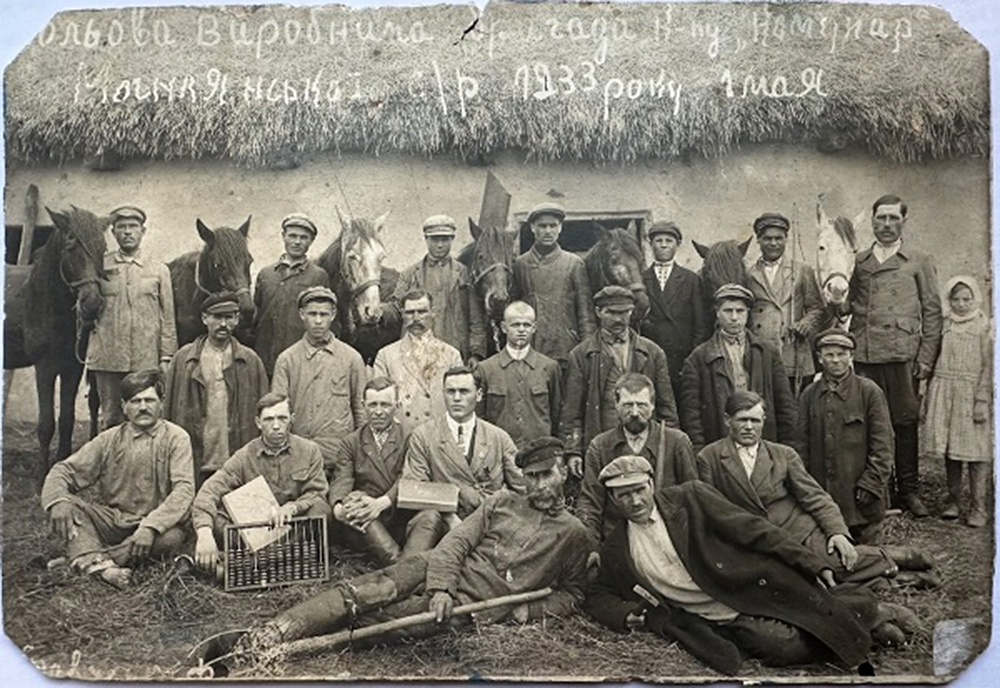

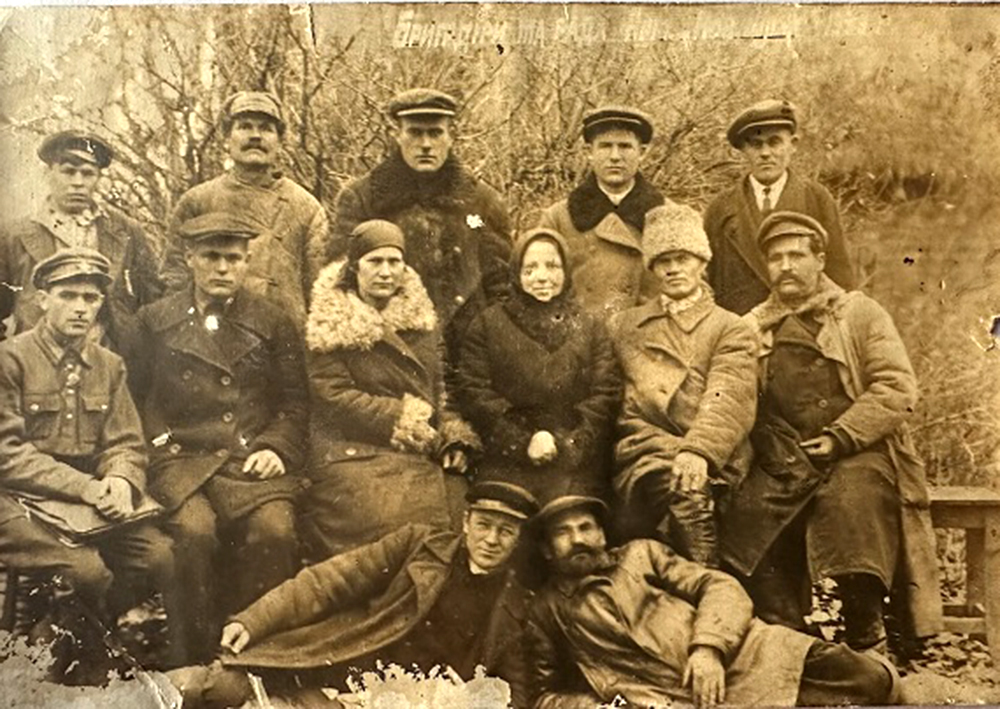

While writing my doctoral thesis, I traveled to villages and cities where, as I learned, some perpetrators lived. I recorded the residents' accounts in audio file format. Unfortunately, while doing this research, I recorded the account of only one perpetrator. I spoke mostly with the children and grandchildren of the perpetrators, who gladly shared their family histories and photographs with me; I use these materials frequently in my articles. There were some refusals when people did not wish to talk about their grandmothers or grandfathers. But most people agreed, and I was very moved by their stories. Thanks to my research outcomes, I realized once again how many people had been involved in the mechanism of the Holodomor. If you did not go to search someone's house, people would search yours. This was a choiceless choice, a phrase that crops up frequently in Holocaust studies. For many people, this became an unspeakable trauma.

For a long time, discussions about the number of Holodomor victims were accompanied by public scandals. From your standpoint, which range of victims (lowest and highest) is accepted and corresponds to the findings of current academic studies? What were the numbers of ethnic Ukrainian victims? Were there other ethnic groups among the victims?

I rely on the estimates of our demographers. Their methods are international and proven, and the most reliable, in my opinion. Some may not agree with me, but this methodology has been tested and verified in peer-reviewed publications, meaning other demographers have anonymously evaluated the research. As a result, demographers agree upon a figure of nearly four million victims of the Holodomor. This is the figure that I use in my publications, lectures, and public appearances. I think that the objective range is between 3.9 and 4.5 million victims. The ethnic breakdown of victims is difficult to determine. We know that members of other ethnic groups died in Ukraine, but it is nearly impossible to provide an accurate tally.

"For two whole years, my grandmother and her sisters ate wild sorrel, thanks to which they survived"

What were the survival strategies of Holodomor victims? What were the features of women's and men's experiences of the Holodomor from the victim's perspective?

Gender, age, place of residence, and even ethnic background defined this experience. If you lived, say, in German colonies or were a Jewish settler, you could ask for help from your relatives, community, or foreign organization. German communities solicited German charitable organizations; Jewish communities turned to the Joint. Consequently, ethnic affiliation sometimes had an impact on survival strategies during the Holodomor. There was once a German colony in a village I visited. Ukrainians lived next to a German Lutheran community, whose members were noted for their high level of solidarity. These colonists were very disciplined because they had to work considerably harder to build up their farms in this desolate area. After the First World War, during which they had been deported to Russia, they returned, only to find that the local peasants had appropriated their farmsteads. So, the colonists started over again from scratch. Of course, their experience of the Holodomor was different, and their mortality rate was considerably lower. However, as soon as these German colonists completed their grain procurement plan, they were given another. In other words, various groups that lived in the Ukrainian SSR suffered and starved.

Different calorie intake levels influenced women's and men's experiences during the Holodomor. Men were targeted first by the authorities, who sought to vanquish potential peasant resistance. Men were the heads of families and the first to be arrested and tormented. Thus, the father figure is often missing from the recollections of Holodomor survivors. At some point, either during collectivization or when the Holodomor was in full swing, fathers disappeared (through death or arrest, etc.). Just like men were the first victims, so, too, were infants whose mothers had lost their milk. In other words, gender or age often affected the chances of surviving. Approximately twelve percent of the population of Ukraine starved to death during the Holodomor. However, the mortality rate among children up to one-year-old was much higher. Women's experience, of course, was also distinguished by the fact that society was patriarchal. Myriad duties were placed on women, who had to take care of their families and do various domestic chores. Oksana Kis describes women's experiences in detail in her work.

Children had more free time and used it to track down unusual foods that helped them survive. Iryna Skubii has written a superb study about the experience of children trying out various animals, plants, and food surrogates because they had more free time off work. They ate mussels and other unfamiliar foods. My grandmother and her sisters ate wild sorrel for two years, thanks to which they survived. Whenever my grandmother cooked green borshch, she never ate it with us. She said, "I've eaten enough to last me a lifetime."

Survival techniques also depended on the geography of residence. In Volyn and Polissia, people ate a lot of mushrooms and went to the woods to hunt game. In the southern steppe regions, people ate gophers. Cats and dogs were also consumed. In late 1933 and even in 1934, there were very few cats in villages, and people complained that there were no cats to catch mice. Many people tried to leave their village and move to a neighboring town.

What was the gender breakdown of perpetrators?

Gender norms influenced the perception of female perpetrators and organizers of the Holodomor. Women did not comprise the majority in village or raion administrations or brigades that searched houses, but women were in these groups. This was shocking to the patriarchal society. This is precisely why people remembered women much more vividly, which often led to exaggerations of their numbers and roles during the Holodomor. According to traditional patriarchal notions, a woman was supposed to take care of her family and be the "protectress of the home" (berehynia). Thus, the presence of women in a sphere of violence that was reserved for men attracted an excessive amount of attention. Such women were frequently depicted as "monsters," and various psychological disorders were attributed to them. A telling example of such exaggerations is the literary representation of the Holodomor in Svitlana Talan's novel Rozkolote nebo (Split Sky) and Leonid Kononovych's book Tema dlia medytatsiï (A Topic for Meditation).

"Percentage-wise, substantially more Ukrainians also died in other republics of the USSR than their neighbors of other ethnic origins"

Is it customary to apply the genocide interpretation of the Holodomor concerning the territories of the USSR outside of Ukraine, for example, Kazakhstan?

My view is that the interpretation of the Holodomor as genocide does not contradict the genocide interpretation of the famine that took place in other regions of the Soviet Union, particularly in Kazakhstan. The famine in Kazakhstan began in 1931 and lasted until 1933. There was a different mechanism at work in that republic because of sedentarization, the process by which the Kazakh nomads transitioned to a lifestyle of living in one place. The nomads were not farmers, and when grain- and meat-procurement plans were issued to them, they lost the only thing that provided a living: their herds. In other words, what we have here is the same artificial character of the famine, the closure of the republic's borders, and the simultaneous persecution of the intelligentsia. The Holodomor was not only a famine but also the concurrent persecution of the Ukrainian political elite, the intelligentsia, and the church. All these processes were also seen in Kazakhstan, but they unfolded somewhat differently, given the country's national characteristics. Historians like Anne Applebaum, Andrea Graziosi, Olga Andriewsky, and Timothy Snyder have pointed out the commonalities between the Holodomor and the Asharshylyk, the famine in Kazakhstan. There are indeed similar features.

It is also worth exploring the artificial famine in the Lower Volga Region — the Volga German Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic — where similar processes and political decisions occurred. In my view, the genocide interpretation offers immense potential for understanding why famine engulfed those particular regions of the Soviet Union. Recent research completed by Natalya Naumenko and her team demonstrates that, percentage-wise, substantially more Ukrainians also died in other republics of the USSR than their neighbors of other ethnic origins. In other words, the policy of famine targeting specific population groups in the Soviet Union, which can be interpreted as genocide, was being implemented. Hence, this particular research focus can be very productive.

"Iryna Skubii and I are planning to write a popular history of the Holodomor"

To overcome the consequences of genocide, the concept of "transitional justice" is often applied. It entails restitution and material compensation for survivors and victims' families; institutional reforms aimed at preventing such crimes in the future; scholarly research focused on determining the fate of victims; and proper commemoration. Has this model of overcoming the consequences of the Holodomor been implemented in Ukraine even to some degree? What has already been achieved, and what else needs to be done to overcome the consequences of the Holodomor and commemorate its victims appropriately?

Earlier, I mentioned court case No. 475, which occurred in 2010. It is difficult to say whether this trial sparked a celebration of justice. Still, this legal recognition had to take place, and it was crucial to declare the criminals and Holodomor organizers the guilty parties. And even though they are no longer alive, their classification as criminals at the state level is important for understanding the Holodomor. Four million people perished, and no one was ever held accountable for this before the law. Of course, the laws were different then; they were adapted to the political decisions of the authorities, like the Law on Five Ears of Grain. But today, as we build a Ukrainian state governed by the rule of law, it is important to render judgment in a court of law, at least postfactum, declaring that this was a crime and clearly identifying its organizers.

There is still much work to be done to establish local justice; there are also many difficulties. The fact is that victims, their children, and the children of perpetrators often married each other or were their neighbors. Since the Holodomor period, everything has changed and become complicated. For that reason, transitional justice at the level of local perpetrators is an extremely complex issue. What has been done so far, such as the identification of mass graves of Holodomor victims, the construction of the Holodomor museum in Kyiv, and memorialization efforts at the local level — crosses erected spontaneously and local museums showcasing the microhistory of the Holodomor — is a very significant achievement in understanding and properly honoring the memory of the victims.

This is probably the ideal model for overcoming the consequences of the Holodomor, as far as it is possible to do this now, when the last eyewitnesses are dying of old age.

Thanks to local efforts, an extraordinary amount of work was done on the national level during Viktor Yushchenko's presidency. It is also important to note the international community's recognition of the Holodomor as genocide. We must see the Holodomor — and here I agree with Anne Applebaum, Timothy Snyder, and Serhii Plokhy — as one of many attempts to subjugate Ukraine since the reign of Peter I or even earlier, when the Russian state (called Muscovy at the time) sought to conquer the Ukrainian lands. Honoring the memory of the millions of dead must become one of the key directions for overcoming the consequences of the Holodomor.

What possible repercussions might Vitalii Ohiienko's rather unsuccessful attempt to write a popular history of the Holodomor have for future academic studies of the Holodomor in Ukraine?

There are two consequences. First of all, publishers and people working with them are now faced with the need to thoroughly review popular history books. They must check whether a book meets the requirements of integrity, not to mention literary and scholarly editing, a process in which other experts in this topic must be involved. The publishing houses Vikhola and Dukh i Litera took a principled stand when they recognized the problem and terminated their collaboration with Vitalii Ohiienko. This is an important and positive shift.

The second consequence pertains to future authors of popular histories and academic studies in general. The importance of citing any ideas or interpretations borrowed from colleagues and the unacceptability of quoting entire paragraphs from the works of other researchers without placing them within quotation marks as a proper citation has garnered attention once again. The copy-and-paste method is no longer workable. It is not acceptable either in the West or Ukraine. I am very heartened to see that most people understand this. Important steps, such as exposing Ohiienko's plagiarism, will improve — perhaps not right away — the overall situation with academic integrity in Ukraine.

Are you planning to write your own popular history of the Holodomor?

Yes, Iryna Skubii and I are planning to write a popular history of the Holodomor; it will be in English. But at the moment, I cannot provide any more details about this project because it is still in the planning stage. I very much hope that the book will come out in the next few years. We want to talk about the Holodomor in the West and see readers interested in this topic. So, wait for it to appear on the shelves of Western bookstores. We are working on it.

Interviewed by Petro Dolhanov

The photographs used in this publication are from open sources and the author's personal collection.

Endnotes

1 Contextualizing the Holodomor: The Impact of Thirty Years of Ukrainian Famine Studies, ed. Andrij Makuch and Frank Sysyn (Edmonton; Toronto: Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies Press, 2015).

Daria Mattingly is a Lecturer in European History at the University of Chichester, UK. In 2019, she defended her doctoral dissertation about rank-and-file perpetrators of the Holodomor at Cambridge University, where she taught Soviet history and was awarded the Leverhulme Early Career Fellowship. She provided research assistance to Anne Applebaum for her book about the Holodomor, Red Famine: Stalin's War on Ukraine (2017). Dr. Mattingly's article "Idle, Drunk and Good-for-Nothing: The Rank-and-File Perpetrators of the Holodomor" won the Association for the Study of Nationalities (ASN) Doctoral Student Prize in 2015. She is on the selection committee of the Danyliw Seminar and, since 2023, on the program committee of the ASN.

Daria Mattingly is a Lecturer in European History at the University of Chichester, UK. In 2019, she defended her doctoral dissertation about rank-and-file perpetrators of the Holodomor at Cambridge University, where she taught Soviet history and was awarded the Leverhulme Early Career Fellowship. She provided research assistance to Anne Applebaum for her book about the Holodomor, Red Famine: Stalin's War on Ukraine (2017). Dr. Mattingly's article "Idle, Drunk and Good-for-Nothing: The Rank-and-File Perpetrators of the Holodomor" won the Association for the Study of Nationalities (ASN) Doctoral Student Prize in 2015. She is on the selection committee of the Danyliw Seminar and, since 2023, on the program committee of the ASN.

Originally appeared in Ukrainian @Ukraina Moderna

This article was published as part of a project supported by the Canadian non-profit charitable organization Ukrainian Jewish Encounter.

Translated from the Ukrainian by Marta D. Olynyk

NOTE: UJE does not necessarily endorse opinions expressed in articles and other materials published on its website and social media pages. Such materials are posted to promote discussion related to Ukrainian-Jewish interactions and relations. The website and social media pages will be places of information that reflect varied viewpoints.