Yaroslav Trofimov on family and Ukraine's deadly 20th-century history

Yaroslav Trofimov has been a leading voice explaining Ukraine and the complexities of the Russo-Ukrainian war, now in its third year, to an international audience.

As The Wall Street Journal's chief foreign affairs correspondent since 2018, he has reported on Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine from its beginning. This coverage resulted in the publication of Our Enemies Will Vanish: The Russian Invasion and Ukraine's War of Independence, which details the first year of Russia's unjust war against Ukraine and its military, political, and social implications. The book received the 2024 Peterson Literary Prize and was a finalist for the 2024 Orwell Prize.

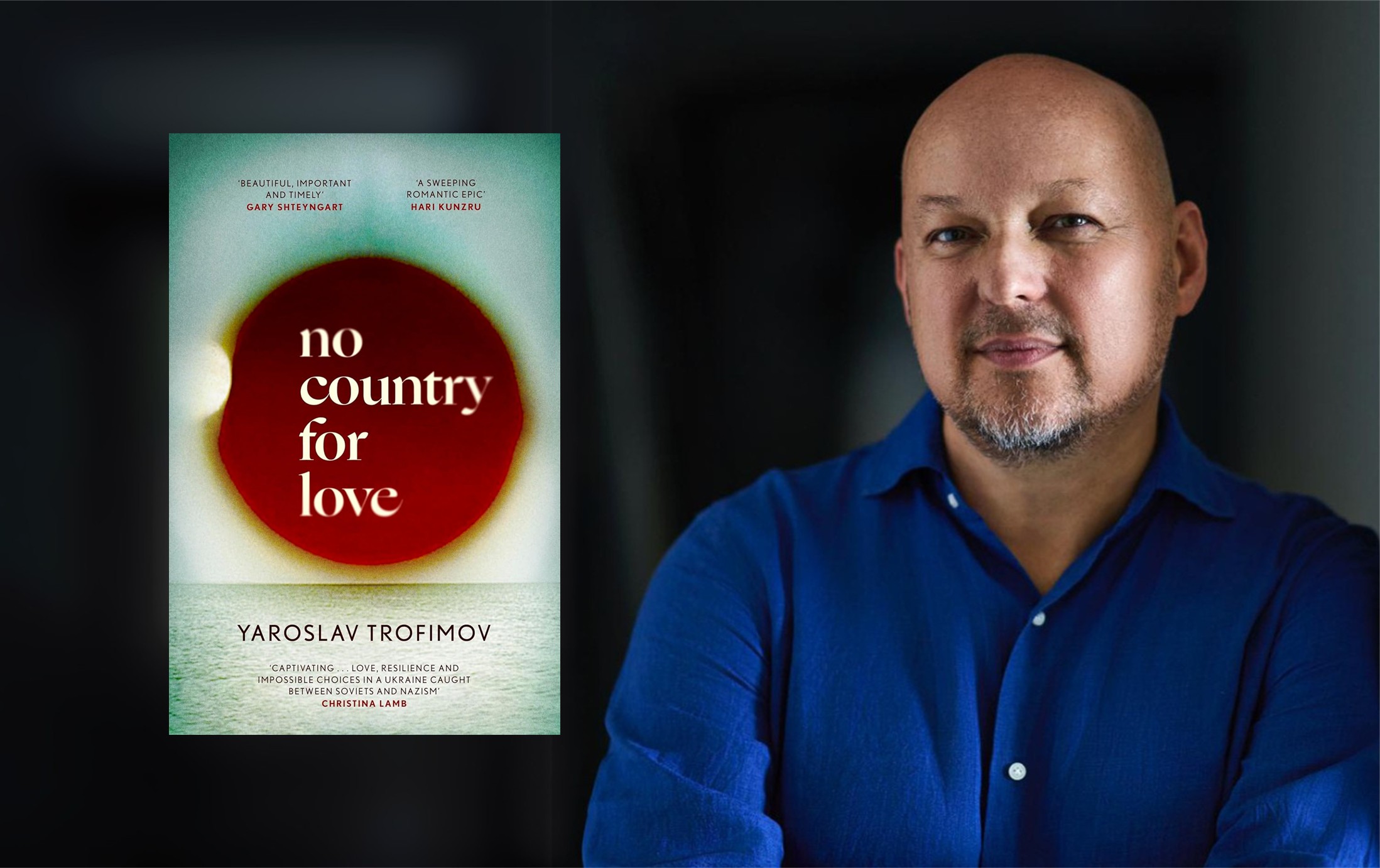

His next book, No Country for Love, makes its North American debut on 11 February 2025.

Set against the backdrop of Ukraine's turbulent 20th-century history, the novel tells the story of Debora Rosenbaum, an ambitious 17-year-old from Uman who arrives in Kharkiv, the capital of the newly established Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, eager to forge a life as a modern woman. Like many of her generation, she is determined to break with the past; the rapid development of 1930 Kharkiv symbolizes a new beginning. She falls in love with Samuel, a fighter pilot in training, and mingles with Ukraine's new cultural and literary elite. Debora's world is quickly shattered as the Soviet Union's political winds change, the promising policies of Ukrainianization are reversed, and repressions begin. Left with a baby after Samuel is sentenced to ten years of hard labor, her journey becomes one of survival.

The book, inspired by Trofimov's grandmother Debora, has already received widespread acclaim. It will be translated into several European languages, including Italian, French, and Portuguese. A Dutch-language edition has been published.

Trofimov, originally from Kyiv, will tour several cities in the United States beginning on Tuesday, 11 February, at the Ukrainian Institute of America in New York to discuss his book and work. The dates and locations can be found here.

Trofimov recently spoke with Natalia A. Feduschak, UJE's Director of Communications, from his base in Dubai about his grandmother, his motivation for writing the novel, Ukraine's turbulent history, and why Ukrainians continue to defend themselves bravely against Russia.

How much of the story is true versus fictionalized?

At the risk of revealing the plot and creating a spoiler, the key pivots in the narrative are true. The characters are true. I took some liberties because some of the actions in the book are things she [Debora] wished she had done but didn't do. The grand finale is true. So, all in all, it reflects the accurate evolution of a character and Ukraine around her. While I did take some liberties with the individual story to make it more compelling, I tried to be as accurate as possible, as faithful as possible with everything around it, with all the historical details, historical descriptions, and markers. There are many secondary characters in the book that are all real, and they're all historically accurate.

Is your grandmother still alive?

No, she passed away in 2008. I had long discussions with her about her life; much of this past was hidden. I didn't know about this when I was growing up. I didn't know about it when I was a teenager. Or even in the first years after the fall of the Soviet Union. I don't have any siblings; I have a cousin. He had no idea about this until I started writing the book. I did take notes and did a lot of research, but I did not know what I would do with this. By the time I started writing the book in 2014, she had already passed away. I couldn't go back to her and ask her more questions. So, I had to work with what I had.

You cover a broad period from the 1930s to the 1950s. Did you choose this timeframe because it is the most relevant to your grandmother's story?

It's the period most relevant to Ukraine's story. It's a period when Ukraine was the deadliest place on earth, between the Holodomor that killed several million and the repressions that eliminated the flower of its intellectual elites. Then, the German invasion, the destruction of the war, the Holocaust, and then the insurgency that followed. That was a period where survival was very difficult and came at a cost, at a moral cost, because to survive, people had to do all sorts of things. The memory of that dark period and the historical trauma of that period are still determining the behavior of people in Ukraine. I think the reason why Ukrainians are fighting so hard right now and refusing to surrender to the overwhelming force of Russia is because so many families in Ukraine are descendants of the survivors of that period. They all know in their bones that surrender to Russia means a return to that dark past. We are seeing this now. When Ukrainians say "never again," the Russians say, "we can repeat it." And in fact, you can see that when the Russians are taking Ukrainian towns, the first thing they do is they demolish the monuments to the Holodomor. They say it never happened; it's all made up by Ukrainian nationalists. I started writing this book in 2014. I was in Afghanistan. I was the bureau chief for The Wall Street Journal, and I couldn't go to Ukraine. I had to oversee coverage of the development of Afghan democracy, which seemed to be a priority for the United States at the time. It looks weird in retrospect. Ukraine was being invaded for the first time, Maidan happened, Russia annexed Crimea, and there was the war in Donbas. I was really perplexed by how little was known about Ukrainian history and how little understanding there was of what Ukraine was fighting for. It wasn't about language. It wasn't an issue of ethnicity. It wasn't an issue of religion. It was an issue of this memory that unites Ukrainians of all stripes because they all went through this meat grinder of history. This is a history that was just not known outside of Ukraine. It was deliberately suppressed and distorted by the Russian and Soviet powers, as was the Ukrainian literature of the time and everything else to do with it. I tried to explain this history through the lived experience of my family. That's a lived experience of the grandparents and great-grandparents of pretty much everyone who is living in Ukraine today.

You paint a complex picture of the Ukrainian-Jewish relationship in this period. I never felt that you portrayed Ukrainians, as too often is the case, as antisemites in a broad brushstroke. Instead, you focus on individuals and their choices rather than generalizing about an entire nationality.

That's the only way to look at things, right? We are all individuals. The basis of humanism is that you reject collective responsibility or collective guilt and look at what individuals did. If you look at what happened in Ukraine, at what people were doing during the Holocaust: some people helped Jews, some people betrayed Jews because they feared for their own lives, and some people were just exploitative and would serve any regime. I recently finished reading a book by Anatoly Kuznetsov called Babi Yar. This is a writer from Kyiv who was 14 when the Nazis came, and he describes it beautifully. He's saying that some of the most ardent collaborators with the Nazis found a very comfortable life under Soviet rule. Nobody bothered them because they could serve any master. He also describes his best friends before the war. When the Nazis came, he realized for the first time that one of them was a Jew, the other one was a Pole, and the third one was a Finn who became a volksdeutsche, allotted the privileges of a German. And suddenly, their paths diverged because of that fact. That was not an issue before the war. It was not even something he knew. If you look at the Jewish-Ukrainian relationship in Ukraine in the 20th century, it's an immensely complex topic. The fact is that in the early years of Soviet rule, there was this policy of nationalities that promoted the development of Ukrainian language identity, Ukrainization, and also promoted the development of Jewish literature, Yiddish theaters, etcetera. But then Stalin's machine cracked down on both. Firstly, the Ukrainian writers and intellectuals were executed in the 1930s, then the Jewish ones when official antisemitism came into place in the 1940s. At the end of the day, the system ground up everyone. I'm trying through this novel to illustrate that, at the end of the day, the world is made of individuals. It came down to individual choices that people made, regardless of what kind of blood they had and what religion they followed. And I think all of them loved the country where they were born and grew up in different ways. We're seeing it now again in Ukraine where nobody's asking soldiers at the front what religion they are, what language they speak. Ukraine now has a Jewish president and a Muslim minister of defense, and that doesn't really seem to bother anyone. Because the identity is not linked to the bloodline.

A prominent Ukrainian intellectual recently noted in a conversation that antisemitism was prevalent in Ukraine when it was part of an empire but lacking when it was not. This doesn't mean it didn't exist on a personal or local level. Would you agree with this assessment?

It depends on the empire. It was prevalent in the Russian Empire because the Russian Empire was antisemitic to the core. The reason Jews were mostly in Ukraine and not in Russia is because of the Pale of Settlement; Jews were forbidden to move to most of what is now Russia. If you look at the Austro-Hungarian Empire, there was a golden age for Jews and Ukrainians in the 19th century. Lviv was a cultural center — for Jewish cultural revival and literature, just as it was for the Ukrainian language and culture and book printing banned in the Russian-controlled part of Ukraine. If you look further back in history at the Polish Commonwealth, it's even more complex because of the interplay of the socioeconomic factors that gave birth to the original Ukrainian antisemitism. If you look at history, the Polish nobility-owned land was managed by Jewish managers imported from Poland. The peasants were mostly Ukrainians. If you look at the history of the pogroms in the 17th century, a lot of that was due to this class struggle element that was colored with religion. This is the history, and it's very complex. You cannot say that Ukrainians are [antisemites] full stop because that's just not true. But it is also true that in the first half of the 20th century, part of the Ukrainian nationalist movement was antisemitic. The nationalist movements in most of Europe were ethnic-based and antisemitic in a way at the time. There's a good discussion about this in Yaroslav Hrytsak's recent book about Ukraine. There he is saying that, yes, it's true, Ukrainian nationalism in the 1930s was antisemitic and fascist in many respects. But that's because Ukraine was looking to the West in its orientation, and this is how most of the rest of Western Europe was. Those were the "Western values" of the day. Ukrainians didn't escape the horrible trend sweeping the rest of Europe at the time.

In the book, you use the word "Yid" instead of "Zhyd" as the pejorative term in dialogues. Why did you choose that word over the other, since they appear to be two distinct terms?

It's just the way it usually translates into English. This is the English equivalent of the Ukrainian slur word. They have the same roots, right? The Ukrainian slur word "zhyd" is a derivative of Judean, and the neutral word "yevrey" is a derivative of Hebrew. They acquired this slur characteristic in some languages and not in others because, in Polish, "żyd" is not a slur.

You point out that Jews knew the Ukrainian language. There is a misconception outside Ukraine that Jews never spoke Ukrainian, only Russian. Was it important to highlight this in some way?

The situation in Ukraine at the time was that the big cities were mostly Russian-speaking, but in the small towns and villages, the lingua franca was often Ukrainian, or the mixed surzhyk. Jews did not live on islands. They would go to the market, and they would interact. They would go to schools. Obviously, they had to speak the language of the people around them, which was Ukrainian, if they were not in the big city. Lots of Jews in Uman knew how to speak Ukrainian. But before the Ukrainization policies were launched, Ukrainian was not the language of education. It was not the language of the written word. For many Jews, embracing Russian was also part of the emancipation, a part of social climbing, if you will. A lot of Ukrainian Jews were dropping Yiddish. They were not learning Ukrainian. They were moving on to Russian, which was seen as the language of culture and social advancement. Not incorrectly, because if you didn't speak Russian, you couldn't really advance socially at the time.

What does the book reveal about Jewish life in Ukraine from your perspective? A new generation of secular Jews was emerging, particularly in larger cities. Debora and her mother, Rebecca, clash over this.

It's not just about Ukraine. Unfortunately, this is the tragedy of Jews across Europe. There was this entire movement of emancipation, the Haskalah, that began in the late 18th century. The thesis was if we abandon the old ways, stop wearing these black frocks, integrate into society, learn the language, and abandon many of our customs, they will accept us as equal citizens if we assimilate enough. Tragically, that did not happen. The German Jews were the most assimilated of the Jews of Europe. Yet they became the first target of the Nazis. You have the same thing with the trajectory of Debora because as she was growing up in the first decade of the Soviet Union, this was an atheist state where it didn't matter officially what kind of religion your parents or grandparents followed. She thought, like so many of the Ukrainians of that generation, she could just become a Soviet person, full stop. Then things changed, and the antisemitism that was not present in the popular discourse in the 1920s and 1930s in Ukraine, or the Soviet Union in general, did stage a massive comeback. It was an import from Nazi Germany. After World War II, it became state policy in the 1940s in the Soviet Union.

One thing I sensed about Deborah was that, even amid all the terrible things the Soviets were doing, she appeared to refuse to accept the system could act this way. In contrast, Rebecca remained clear-eyed.

I think that's because people of the older generation had seen a different way of life. Meanwhile, a girl who was 17 in 1930 didn't have any memories of a much freer life in Ukraine before 1914, when the First World War began. So, there was nothing to compare it to. She didn't experience life that was not under the totalitarian system that could do anything to you. Czarist Russia in previous decades was no liberal paradise, but it was immensely freer than the Soviet Union ever was in terms of personal liberties. They did not execute revolutionaries. Lenin and other leading Bolsheviks spent a few years in prison and then were exiled to Switzerland, Finland, or elsewhere in Europe. The level of repression is incomparable. If you have never experienced a different system or a different life, it's very hard for you to reject what you see because your scale of reference is different. If you look at Ukraine in the 1960s, the 1970s, and the 1980s, there were people in Western Ukraine who remembered the non-Soviet life in their childhood, whereas no one in Central-Eastern Ukraine remembered that, which explains why there was a strong dissident movement there.

By the end of the book, I couldn't decide who was luckier: Samuel, who had endured all this horror, appeared to be a more optimistic figure and a true survivor, or Debora.

It was not survival just for her own sake; it was survival for her children's sake. She had to do things she regretted. She had to compromise on her purity and principles, which Samuel didn't have to do because he was a prisoner. I mean, everybody's a tragic figure in this book. You could not survive this system then without losing part of your soul. This is also why people don't talk about these histories in Ukraine. Because people are very often ashamed of telling the truth. I had a reading for this book in Scotland, and lots of second and third-generation Ukrainian families came to listen to me. They were saying, 'I wish my grandmother could tell me all this,' but they always refused to talk about this because there was so much shame over all the things they had to do to survive — because it wasn't easy to survive.

You avoid a sweeping approach in addressing the Holocaust, focusing instead on Babyn Yar. In just a few profoundly moving paragraphs, you described the fate of Kyiv's Jews. Why did you choose to keep it so narrowly focused?

I wanted to focus on her. Deborah was not there during the Holocaust, so all the information she is getting is second-hand. I wanted to highlight the fact that it was probably the first mass execution of Jews as the Holocaust began; it was the Holocaust by Bullets. It was even before the gas chambers. And that tragedy was hidden after the war. The Soviet Union did not want to acknowledge that Jews were killed there [Babyn Yar] when they built the monument there. It just said, Soviet citizens. They tried to destroy the site and build a stadium on top of it. Then, the dam burst and killed hundreds of people in Kyiv in the 1960s. So, by itself, it's not just a symbol of Nazi atrocities; it's also a symbol of Soviet efforts to hide and distort history.

Interestingly, a German woman relays the fates of Debora's father and Kyiv's Jews.

There were good and bad Ukrainians and good and bad Jews. There were Jews who also collaborated with the Nazis. Not a lot, but there were a few. There were also good Germans. I'm returning to the idea of collective responsibility, which is an evil concept by itself and the cause of so many troubles in the 20th century. We have to look at individual choices that everyone makes.

The Slovo Writer's House in Kharkiv plays a significant role in the book. The fates of the Ukrainian writers and artists who lived there are now becoming more widely known throughout Ukraine. What inspired you to include this setting in the book?

I have always been interested in this, the Executed Renaissance. I've been reading many writers of that time, like [Valerian] Pidmohylnyi and others that are sadly unknown to the English reader. They have not been translated until now. That was the great Russian success in wiping out Ukrainian literature; it remains unknown even 100 years later. A lot of these real-life authors are introduced in this book. I'm just using the first names. But I had a talk where the moderator was a student of Ukrainian literature, and she very quickly realized who was who and was very excited at identifying them and their works. It goes back to where I tell the story of Ukraine through Debora. I'm introducing another real-life character, Walter Duranty of The New York Times, the reporter who whitewashed Stalin's annihilation of millions of Ukrainians during the Holodomor. So, lots of real-life characters are making an appearance there.

You also allude to Gareth Jones. However, you don't use the word "Holodomor" in the text, but rather famine. And you don't say Stalin instigated it, which some people may take issue with.

It's a novel, right? I did use it in non-fiction books. But the people living through the Holodomor did not call it Holodomor. Just like those living through the Holocaust did not have a word for it just yet. It all came later once the scope and scale of these tragedies became known. The entire approach to the book is, you are there. I'm trying to be as cinematic as possible and have as little a narrator voice as possible.

Readers learn about the Ukrainian national movement, which is taking place in Western Ukraine, through the characters who live in Kyiv. This literary device creates a distance from the events.

Right. The violence was mostly in Western Ukraine. But obviously, it was affecting everyone. It only ended with Stalin's death and the Kremlin's decision to offer concessions and free many detainees, though obviously not all. But it was part and parcel of the lived experience at the time. In this part of the narrative, I'm trying to stick to the actual facts of the family history.

Do you see Deborah as a tragic figure or as a heroine, or does it depend on what perspective you're coming from?

Well, I mean both, right? It's obviously a tragic life, and obviously a lot of her hopes and expectations were dashed, and she lost a tremendous part of herself in that process. And yet she didn't just succumb to the circumstances. She ended up acting, which is more than many other people. That's the story of the entire generation.

What about her children?

I took a lot more liberties with the children. The real Pasha did not go to the KGB but he retained an affection for his stepfather. As it says in the beginning, it's based on her life.

You published two books about Ukraine within the last year. Do you plan to write more about Ukraine?

I'm trying to work on another novel that is also inspired by my family history. It brushes into Ukraine, but it's also set in other places. It's also a murder mystery, not that my parents murdered anyone! I've started putting it together, but it takes a while. It took eight years for this novel. Novels are complicated.

Yaroslav Trofimov

Yaroslav Trofimov is the author of three books of narrative non-fiction and one novel. He has worked around the world as a foreign correspondent of The Wall Street Journal since 1999, and has served as the newspaper's chief foreign-affairs correspondent since 2018. Born in Kyiv, Ukraine, he was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in international reporting in 2023, for his work on Ukraine, and in 2022, for his work on Afghanistan, and won the National Press Club award for political analysis in 2024. His honors include an Overseas Press Club award for coverage of India as well as the Washington Institute gold medal for the best book on the Middle East. His latest non-fiction book, Our Enemies Will Vanish, was a finalist of the 2024 Orwell Prize and won the 2024 Peterson Literary Prize. No Country for Love is his first novel. He holds an MA from New York University.