"You are all my kin, and I am your kin"

[Editor's note: Russia's unprovoked and criminal war against Ukraine suspended the regular work of many organizations, reorienting their efforts. So it is with the Ukrainian Jewish Encounter. In the coming weeks, we will run interviews and articles done before the beginning of the war, which reflect the myriad of interests undertaken by Ukrainian journalists, scholars and writers.]

Originally appeared in Ukrainian @zaxid.net 9 September 2021

About a Ukrainian Righteous Among the Nations who perished in the GULAG

Yad Vashem several days ago updated its statistical data on the Righteous Among the Nations on its website. In 2020 this title was awarded to fourteen more citizens of Ukraine. Thus, as of 21 January 2021, their numbers stand at 2,673 people.

In and of itself, this figure says little. It is obvious that there were more people who helped Jews during the Holocaust, but for various reasons, their stories have not come to light. For example, Jewish children left their rescuers and eventually forgot their names. What remains in their memories is just the "uncles" or "aunts" who let them into their houses and hid them in cellars or attics. You can run across these topics while reading the memoirs of survivors. That said, the relationship between the rescued and rescuers did not always end after the Holocaust.

Ilya

In December 1942, twelve-year-old Ilya Kelmanovich was roaming around the villages surrounding Kamianets-Podilskyi. He was one of several dozen surviving Jews seeking rescue among the local peasants. Only a few of them would succeed.

Half a century later, Kelmanovich would recount his experiences in front of a video camera in his New York City apartment. In late August 1941, he managed to save himself during the mass killings in Kamianets-Podilskyi, where over a period of three days, the German SS and policemen shot 23,600 Jews. This was the second-largest mass killing during the Holocaust in occupied Ukraine, after the events in Babyn Yar in Kyiv. For the first time, everyone, regardless of age or gender, was killed: men, women, and children — "all of Kamianets-Podilskyi" — according to Kelmanovich. Among the victims were his father, his ten-year-old brother, and two sisters, aged six and four. At the last moment, Kelmanovich managed to persuade a local policeman that he was a Ukrainian who had accidentally ended up at the mass killing site. This saved his life.

Half a century later, Kelmanovich would recount his experiences in front of a video camera in his New York City apartment. In late August 1941, he managed to save himself during the mass killings in Kamianets-Podilskyi, where over a period of three days, the German SS and policemen shot 23,600 Jews. This was the second-largest mass killing during the Holocaust in occupied Ukraine, after the events in Babyn Yar in Kyiv. For the first time, everyone, regardless of age or gender, was killed: men, women, and children — "all of Kamianets-Podilskyi" — according to Kelmanovich. Among the victims were his father, his ten-year-old brother, and two sisters, aged six and four. At the last moment, Kelmanovich managed to persuade a local policeman that he was a Ukrainian who had accidentally ended up at the mass killing site. This saved his life.

The Jewish boy found himself all alone in a new world: "You couldn't step outside anywhere. Your enemy was at every step. You didn't know where you were supposed to hide. I had to adapt. I had to sleep on the street. I spent days in the forest with which I had never been familiar." Fear of strangers was combined with the need to turn to them constantly in order to survive. In every village that he went to, he tried to find the poorest-looking house, ask for something to eat and a place to spend the night. He bypassed the ones that looked more well off because he was afraid of encountering a local policeman or village elder. All the while, he pretended to be a Ukrainian who had lost his parents during a bombardment, and he even invented a new name for himself: Zhora Vlasiuk. "I didn't say who I was. I said that I was an orphan. I spoke pure Ukrainian. If I had said that I was a Jew, no one would have taken me," Kelmanovich said.

That is how he ended up in the village of Slobidka-Rakhnivska in December 1942.

Mykhailo

The SBU [Ukrainian Secret Service] archives in the city of Khmelnytsky contain thousands of criminal cases against individuals who were convicted for collaborating with the Nazis. These were local policemen, village elders, the heads of municipal and raion [district] administrations, translators, informers, and propagandists. The sentences varied from ten years' imprisonment to the death penalty. Most of these cases have never been examined by researchers.

On 12 July 1948, a sentence was handed down to Mykhailo Uzhytsky from Slobidka-Rakhnivska. The investigation into his case was very brief. A little more than a month passed between the time of his arrest and his trial. Uzhytsky was sentenced to 25 years with confiscation of property, and he was stripped of his rights for five years.

On 12 July 1948, a sentence was handed down to Mykhailo Uzhytsky from Slobidka-Rakhnivska. The investigation into his case was very brief. A little more than a month passed between the time of his arrest and his trial. Uzhytsky was sentenced to 25 years with confiscation of property, and he was stripped of his rights for five years.

Today Viktoriia, the youngest of Mykhailo Uzhytsky's nine grandchildren, lives in his house in Slobidka-Rakhnivska. She never met her grandfather; she has only seen him in photographs in the family album. At one point, she tried to learn about his case, but she did not succeed. She knows about her grandfather's fate from the accounts of older relatives or fellow villagers.

At the time of his conviction, Uzhytsky was 59. He had a family: a wife, Bronisława, a son, and two daughters. They were Roman Catholics. They were Poles by birth but registered themselves as Ukrainians for fear of persecution at the hands of the Soviets. In the Soviet-Polish border area in the 1930s, practically every single Pole was suspected of being a potential spy. Uzhytsky changed jobs several times, and in 1931 he even became the head of the collective farm in the village of Hannivka. In 1933 he was sentenced to two years imprisonment for "squandering collective farm property." During the Holodomor, a similar fate befell many village functionaries who had provided starving peasants with food taken from collective farm stores. Had Uzhytsky done the same thing? Viktoriia recounts some family stories: "In the spring, when we went out for the sowing, the people who came were very hungry and weakened; they would fall down. So, from every sack, he took out a handful of grain — he thought that no one would see this way — and he let them cook some sort of gruel." According to statistics, during the Holodomor, nine people died in Hannivka and in neighboring Nesterivtsi — 52 (for the purpose of comparison).

During a meeting held in September 1942, the villagers elected Uzhytsky as the village elder. Besides Slobidka-Rakhnivska, he was also in charge of the neighboring villages of Hnylovody and Slobidka-Zalisetska, around 200 households. He held this position until the arrival of the Red Army. The main accusation leveled against him during the investigation was his involvement in mobilizing peasants to forced labor in Germany. Although Uzhytsky admitted this, he insisted that even though the plan that was sent to him indicated 260 forced laborers, only 16 were sent. Among them was his own son, Tymofii, the father of Viktoriia. He claimed forcefully that he had taken advantage of his acquaintances on the medical commission, from which he obtained certificates for his fellow villagers stating that they were unfit for work. That is why so many were sent back home.

There were also attempts to accuse Uzhytsky of beating his fellow villagers, but they themselves denied this during the trial. It is likely that initially, the investigators forced some people to make false statements. Viktoriia recounts the story of a neighbor woman of her Aunt Jadwiga's: "When she was dying, she told my aunt: 'I want to die with a clear conscience and ask for your forgiveness for having testified against your dad during the trial; I had to say what they asked me to.' My aunt forgave her."

During the trial, another telling fact was revealed. Olena Kukharska from Slobidka-Rakhnivska testified that during the occupation, she hid a Jew in her house. In the spring of 1944, someone reported this to the German soldiers, and they wanted to burn down Kukharska's house. She asked for Uzhytsky's help; thanks to his intervention, the house was not burned down. Two days before the Red Army arrived, he found out from Kukharska that she had indeed hidden a Jew.

Іlya and Mykhailo

Kelmanovich was also one of the witnesses in Uzhytsky's case. The investigator questioned him on 8 July 1948. "In December 1942," he testified, "I entered the village of Slobidka-Rakhnivska, where Mykhailo Vikentiovych Uzhytsky was working as the head of the village administration. I lived in the village for four days. Uzhytsky said that I was a Ukrainian by nationality who had been evacuated by the Germans from Stalingrad oblast; I have no information about my relatives." As the village elder, he reported about the boy to the German gendarmerie in the raion center of Dunaivtsi. At first, they said that he should be sent to Germany for forced labor, but Uzhytsky objected, saying that he was too young. Then they ordered the boy to be brought to Dunaivtsi, and there the gendarme asked him through an interpreter whether he was a Jew. Uzhytsky insisted that he was a Ukrainian. Kelmanovich testified further: "At the gendarmerie Uzhytsky, as the head of the village administration, obtained permission to register me in his village. When we returned from the city of Dunaivtsi, Uzhytsky's daughter, Jadzia, told her father, Uzhytsky, to let me live in his house. Uzhytsky left me in his house, and I lived with him, grazed his cattle and did chores on his farm during the entire occupation period, that is, until March 1944."

Kelmanovich called Uzhytsky and his wife the local way, as Uncle and Aunt; they called him Zhorzhyk. The investigator asked whether Uzhytsky knew about Kelmanovich's Jewish background. He explained: "At first, when I was living at Uzhytsky's, he did not know that I was a Jew by nationality, but eventually, I don't remember what month it was, in the spring of 1943, Uzhytsky found out that I was a Jew by nationality, but he didn't say anything about this." Viktoriia recounts that the little boy yelled in his sleep. The grandmother, who had lived for a long time in a Jewish milieu, recognized the Yiddish language. To make sure, they removed his pants. Then they began to act more responsibly: They forbade Kelmanovich to go out in public and to go to the river; they shaved his head and taught him some Roman Catholic prayers. In dangerous situations, he would race over to the home of Liudmyla, Uzhytsky's oldest daughter, who lived in Hnylovody. One day someone reported that the Uzhytskys were hiding a Jewish boy. Two local policemen came to the house, but Kelmanovich had been warned in time, and he hid. Uzhytsky complained to the German soldiers who were in the village, saying that they wanted to rob him, and they chased away the policemen. He assured the villagers that the boy had been checked; he was not a Jew.

In April 1945, Uzhytsky was drafted into the Red Army. He did not end up at the front and returned home within a few months. Afterwards, he worked on a collective farm. Kelmanovich continued living for some time with the Uzhytskys until his two uncles and their families returned from evacuation and took the boy with them. He continued to visit his rescuers. When Uzhytsky was arrested, he testified on his behalf. Kelmanovich recounted later that the investigator tried to intimidate him: "Then he says to me: 'You're not telling me the truth. If he had known, he would have hanged right away.' I say: 'No, he didn't know.' 'Then you worked together with him,' he says."

In any case, the fact that a little Jewish boy had been saved was of absolutely no interest to the investigation. Three days after his conviction Uzhytsky wrote a complaint. It was rejected. His subsequent fate could only be partially reconstructed. Initially, he ended up in an "invalids' colony" in Ostroh, Rivne oblast, and from there, he was sent to Karlag, in Kazakhstan, one of the largest camps in the GULAG, and, finally, to the large village of Sora in Krasnoiarsk Krai. This was the location of the Yeniseistroi camp, the prisoners of which were used to build industrial installations. The family tried to support him with packages. Kelmanovich helped, too: "The whole time, we stayed in touch. I gave them money. They sent it to him there."

Viktoriia kept a few of her grandfather's letters "from far-away Siberia," as he wrote. He assured them that he was alive and well and hoped to return home and see his family. In a letter dated 5 January 1951, he says that he is sending his portrait for which he had to pay the camp artist half of his monthly pay that he earned as a Soviet prisoner: "My portrait came out very accurately, just as though I am alive. It cost me 50 karbovantsi. Let this be a souvenir for you." This portrait still hangs on a wall in Viktoriia's house. The last letters from Uzhytsky were written by another prisoner. He was sick: "He doesn't speak, he only keeps his hand on his head and shows that it hurts."

On 14 October 1955, Uzhytsky's case was reviewed, and it was decided to reduce his prison sentence to ten years and to amnesty him — to be released, and his criminal case expunged. After this, the bureaucrats' correspondence in connection with the search for Uzhytsky within the bowels of the GULAG lasted for another month. They finally determined that he had died on 9 September 1951. His burial place is not known. Viktoriia recalls that a man came to visit them in the 1970s, the son of her grandfather's fellow prisoner. They learned about his grave from him — "not a little cross — nothing but a small plaque and an inscribed number."

On 14 October 1955, Uzhytsky's case was reviewed, and it was decided to reduce his prison sentence to ten years and to amnesty him — to be released, and his criminal case expunged. After this, the bureaucrats' correspondence in connection with the search for Uzhytsky within the bowels of the GULAG lasted for another month. They finally determined that he had died on 9 September 1951. His burial place is not known. Viktoriia recalls that a man came to visit them in the 1970s, the son of her grandfather's fellow prisoner. They learned about his grave from him — "not a little cross — nothing but a small plaque and an inscribed number."

The entire time Kelmanovich was in touch with the Uzhytsky family, and whenever possible, he visited Slobidka-Rakhnivska. Viktoriia says: "He always called us his kin. For him, grandmother was his mother; that's what he said." The last time they saw each other was before his emigration. "I went to say goodbye to them" — at this point Kelmanovich sobs and wipes away his tears with a handkerchief. "They told me not to go, but to stay with them."

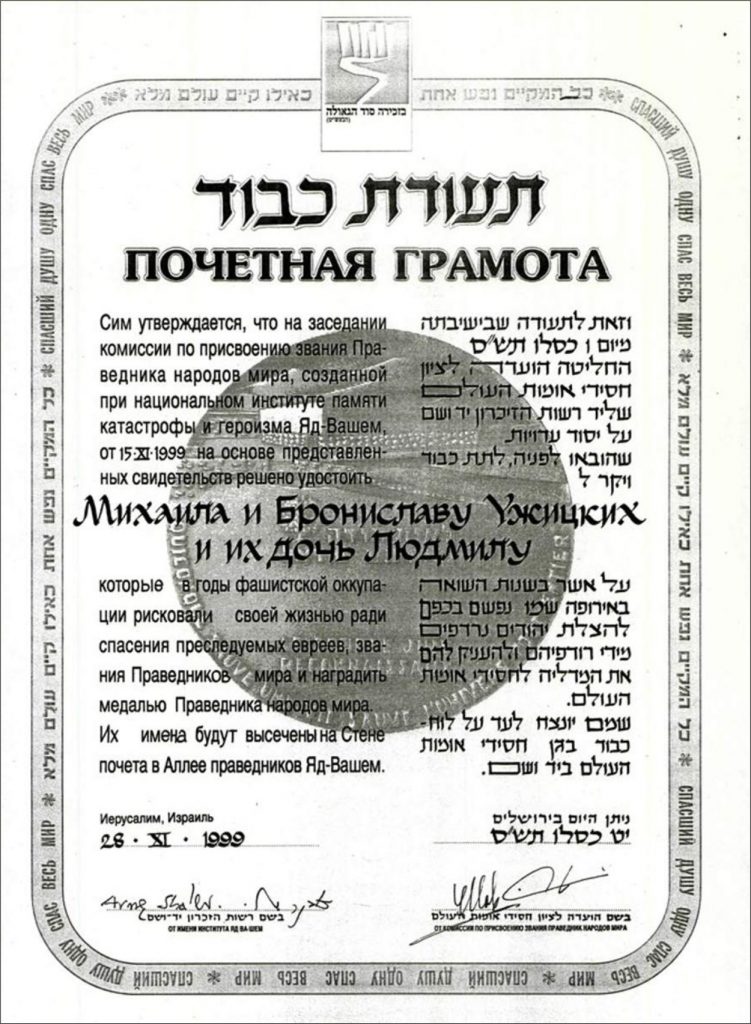

On 15 November 1999, Yad Vashem awarded the title of Righteous Among the Nations to Mykhailo Uzhytsky, his wife, Bronisława, and his oldest daughter, Liudmyla. It was awarded only to her, the last one alive. Kelmanovich insisted that the youngest daughter, Jadwiga, be awarded the title of Righteous Among the Nations, but his request was denied because minor children are not awarded this title. Jadwiga died two years ago, and a year later — Kelmanovich. To the very end, he kept in touch with the descendants of his rescuers. Viktoriia has kept the letters from Kelmanovich from New York. In one of them, he writes: "All of you are my kin, and I am your kin."

P.S. During the writing of this article, the author studied the criminal case against Mykhailo Uzhytsky held at the SBU Archive in Khmelnytsky oblast, the oral-history interview with Ilya Kelmanovich held at the USC Shoah Foundation Institute for Visual History and Education (University of Southern California), and the Yad Vashem archival dossier on granting the Uzhytsky family the title of Righteous Among the Nations. The author is particularly grateful to Viktoriia Buhutska and Nataliia Koblia, the granddaughter and great-granddaughter, respectively, of Mykhailo Uzhytsky, for their consultations about their family history, as well as photographs and documents from their private archive.

The author will be grateful for any information on other cases during the Holocaust in occupied Ukraine.

Andriy Usach, 20:00, 9 September 2021

This article was published as part of a project supported by the Canadian non-profit charitable organization Ukrainian Jewish Encounter.

Originally appeared in Ukrainian@zaxid.net

Translated from the Ukrainian by Marta D. Olynyk.

Edited by Peter Bejger.