The Zaporozhian Sich and the Jews: Complicated relationships and unexpected roles

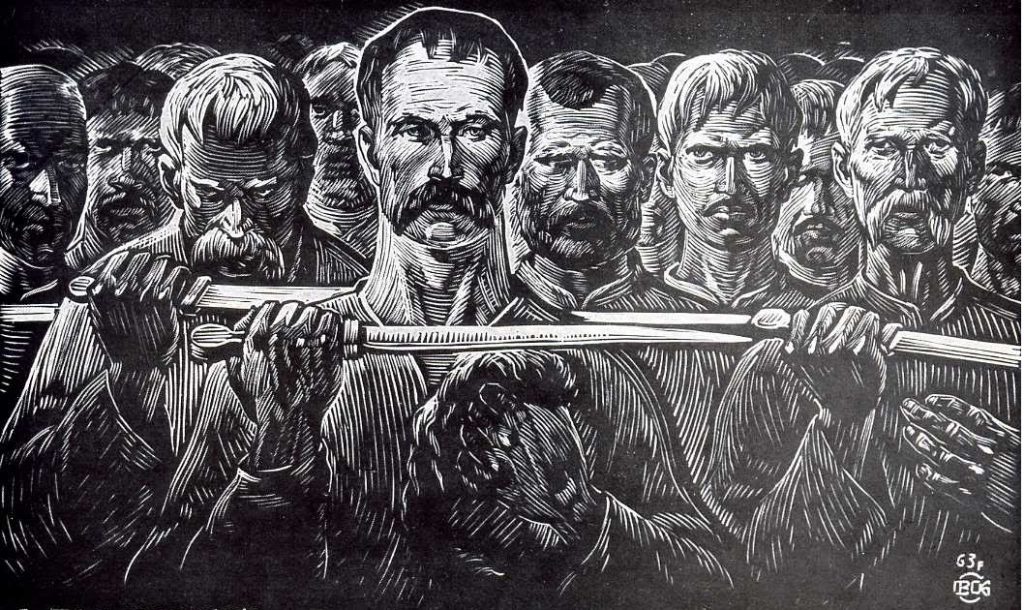

The historian Volodymyr Liubchenko talks about the difficult relationship between Jews and the Cossack Sich in the eighteenth century, the haidamaka rebels, and myths around this period.

Andriy Kobalia: Good day. This is the program Encounters, created by the Canadian philanthropic fund Ukrainian Jewish Encounter. Andry Kobalia is with you at the microphone and today we will be talking with the historian Volodymyr Liubchenko about the relationship between Jews and the Zaporozhian Sich in the eighteenth century. Let’s begin with a very basic question. In order to become a Cossack, one had to be of the “Greek” or Orthodox faith. So, this is interesting. Could a Jew become a Cossack?

Volodymyr Liubchenko: Like a member of any ethnic group who volunteered to accept the Orthodox faith, that is, to convert, a Jew could become a Zaporozhian Cossack. And we have not very many but some examples of such actions on the part of individual Jews.

This was often not an option for the Jew himself because the Cossacks often took small boys as prisoners in the lands where the Cossacks conducted their operations. We have examples indicating that during their sorties into the lands of the Ukrainian voivodeships of the Rzeczpospolita [Polish state—Ed.], they captured Jewish boys in the Kyiv or Bratslav region, took them to the Sich, converted them, and later, when these boys became adults, they became Zaporozhian Cossacks. There are these examples. But there’s another example. Even as adults, Jews from certain déclassé elements of the Jewish population made such a choice of their own free will. They accepted conversion either in the Rzeczpospolita or the Sich and became Zaporozhian Cossacks.

Andriy Kobalia: Do we know anything about how these people who converted were treated? Could there have been persecution on the part of people who were Orthodox from birth?

Volodymyr Liubchenko: We are talking about the eighteenth century and you have to take into account that the world was still not familiar with racial theory. Therefore, the attitude toward Jews or any other ethnic groups was in no way determined by racist reasoning, which is characteristic of the second half of the nineteenth and the twentieth centuries. Yes, the religious factor was of great importance, but once a person changed religions, he became absolutely equal to others, and the Cossacks absolutely tolerated those Jews who accepted Orthodoxy and became Cossacks.

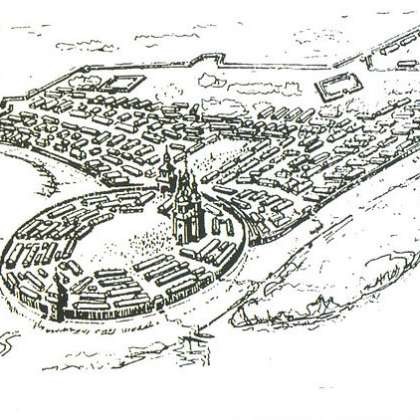

Andriy Kobalia: I know that in addition to this role, Jews in the Sich performed others, that of merchants. When did they appear in the Sich?

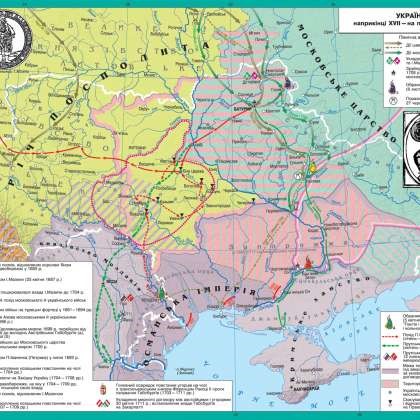

Volodymyr Liubchenko: Close economic relations between the Zaporozhian Sich and Jews living in the border voivodeships of the Rzeczpospolita emerged in the last decade of the Zaporozhian Sich’s existence. The origins of these economic contacts lay in the dramatic history connected with the consequences of the haidamaka uprising. In 1771, during the Russo-Turkish campaign, in which the Zaporozhian Cossacks also took part, the Zaporozhians captured part of the encampment of the Crimean khan Qirim Giray in the Nogai steppe. Among their trophies were five hundred Wallachians and nearly a hundred Jews from the Bratslav town of Yanovo, who had obviously ended up in Qirim Giray’s encampment, having earlier escaped the Koliivshchyna rebellion [a major haidamaka uprising—Ed.].

What is interesting to us is what the Cossacks did with the captured Jews. They released the Wallachians because they were Orthodox. They kept the Jews and drafted a letter, designated several plenipotentiaries, and dispatched them to the lands of the Rzeczpospolita, to the large trading center of Uman, where fairs took place every year, so that the Jews would appeal to their coreligionists and raise the necessary sum of eight thousand rubles for their release from imprisonment.

Andriy Kobalia: How large a sum was this at the time?

Volodymyr Liubchenko: It was a colossal sum. The chief agent of this group of Jews was Shmuilo Markovych, who was active in the lands of the Rzeczpospolita in the effort to raise the necessary sum. One year passed. The delegated Jews returned to the Zaporozhian Kish [Camp—Ed.] with the news that they had failed to gather the funds because of the pitiful situation of the Jewish population following the Koliivshchyna rebellion; they had collected only six hundred rubles. The Jews asked [the Cossacks] to take pity on them and be satisfied with this sum. Obviously, the Jews had also appealed to Count Rumiantsev, who also wrote a letter to the last koshovyi otaman [military leader—Ed.] Petro Kalnyshevsky and requested that he limit himself to this sum. Oddly enough, the Cossacks agreed.

By October 1772 they released the seventy-seven Jews who were still in their hands at the time. Perhaps some had been able to purchase their freedom independently, outside the framework of this deal. In releasing them, Petro Kalnyshevsky wrote a letter to the Jews in adjacent voivodeships, declaring that he would not object to the Jews coming to the Sich as merchants. This correspondence between Kalnyshevsky and Shmuilo Markovych and Maiorko Maiorkovych, the first Jewish merchant from Uman to arrive in the Sich, gave rise to very close trade relations between the Jewish merchants of the Bratslav area and the Zaporozhian Cossacks.

This represented a reorientation of trade by the traditional Zaporozhian Sich, a polity that had always been oriented on the Crimea and the Ottoman Empire, where the Russian government interfered in all sorts of ways in the mid-eighteenth century. The Russian government restricted this trade. For that reason, the Cossacks focused attention on Jewish merchants in the border voivodeships of the Rzeczpospolita.

Andriy Kobalia: But I see a few obstacles. We know that in the preceding decades there were no Jews in the Sich. With what are these changes connected? And how could the Jews, after the Koliivshchyna rebellion in which the Zaporozhian Cossacks also took part, travel to the Sich, to the very people who had been killing them not so long before? How is this possible?

Volodymyr Liubchenko: It is not entirely correct to say that there were no Jewish traders before this time. How easy was it for Jews to decide to go to the Sich? First of all, Jewish population losses resulting from the Koliivshchyna rebellion, as well as from the Khmelnytsky rebellion. were extremely exaggerated by contemporaries of these events. Far from all of the Jewish population of Uman was exterminated. Otherwise, it would be very difficult to explain such a rapid recovery of the Jewish population in the city. The same can be said of the subkahals, inasmuch as it is believed that many Jews from surrounding villages and towns who had fled to Uman perished. Data from the 1775 census attest that even the rural Jewish population practically did not decrease in comparison with 1765.

Andriy Kobalia: We have already mentioned the haidamaka rebellion and Right-Bank Ukraine several times. One often hears that in the eighteenth century the Jews in these lands were a kind of intermediary between Polish landowners and the local population, that the Jews were supposedly bleeding people dry and controlling these lands. Why the Jews, precisely?

Volodymyr Liubchenko: That was the reality. The society of the Rzeczpospolita required a class that could carry out a certain socioeconomic function. As a rule, Polish magnates did not deal with this. Jews, as educated, free, urban residents who had several centuries of experience with economic activities, became this class. Thus, Ukrainian antagonism in relation to the Jews was determined not so much by the religion of the Jews as their social function. We won’t say that Jews carried it out under duress. They sought the most advantageous opportunities. This social function offered them the most advantageous living conditions in the Ukrainian territories of the Rzeczpospolita.

Andriy Kobalia: The leaders of the haidamaka uprisings often made use of fake documents stating that the Russian empress or emperor was allowing them to exterminate the Jews. For example, we know about Catherine the Second’s “Golden Charter,” which was utilized during the Koliivshchyna rebellion. I cite: “Because we know the hatred and contempt that the Poles and Jews have for us and for our Orthodox religion, persecuting, humiliating, and even punishing by death the defenders of our Greek religion…we order that all Poles and Jews who trample our holy faith be destroyed with God’s help.” The Jews and Poles are paired up here. Did the Jews truly oppress the Orthodox faith? Did they truly seek to restrict the rights of the Orthodox? I recall a story, or myth, that Jews supposedly kept the keys to churches, and if a Jew felt like it, there would be no service. What is hidden behind this?

Volodymyr Liubchenko: If we are touching on the myth of the keys to churches, which the Jews had in their possession, then it should be noted that this myth predates the eighteenth century, but it was mentioned precisely in this century and at the beginning of the nineteenth, when it was put forward as the main reason behind the destruction of the Jews during the Khmelnytsky era. Researchers of Bohdan Khmelnytsky’s rebellion say that the Jewish theme was of rather secondary importance. Motifs about Jews leasing churches and the Jew who has the keys [to a church] and of his own free will allows or does not allow Orthodox services to be held during the Khmelnytsky period—this motif was practically not utilized, emerged much later, and was borrowed from Polish sources.

In 1649, that is during the Khmelnytsky uprising, a Polish Catholic priest, Pawel Ruszel, mentions that he heard from people that the Jews have become so powerful in the Rzeczpospolita that these intermediaries grant or do not grant permission of their own free will. But at the same time he also writes about Catholics, not just about the Orthodox. Could this myth have had a historical basis? Formally, yes. Estate owners possessed the right of patronage vis-à-vis those religious communities that were located on their lands. Thus, whereas in the eighteenth century entire villages and keys were handed over to the Jews, which was not characteristic of this century, in the seventeenth century there was some basis to this legend. But we do not have adequate documented confirmation of this. There is a leasing agreement from as early as 1596 from the Kholm region, in which the Polish nobleman Jakub Laskowski and the Jew Peisach leased an actual village in the Kholm region. A church is also mentioned among the revenues. We do not have other documents of this kind.

The main point is that for Khmelnytsky’s contemporaries this motif did not play any role and was not mentioned. In other words, the farther away from the events of the Khmelnytsky period the more perfect were the forms that this myth acquired, thanks to Polish historiography. We can mention Polish authors of the 1670s and 1680s, Samuil Grądzki and Wespazjan Kochowski, who developed this motif. Later, from their successful venture, this motif ends up in Cossack chronicle writing as early as the beginning of the eighteenth century. We still do not find this subject in the first Cossack chronicle of the seventeenth century, Litopys samovydtsia [Chronicle of an Eyewitness], but in the Hrabianka chronicle, the leasing of churches by Jews is first mentioned. Later, during the period of the Koliivshchyna rebellion, this myth acquires a more complete form, especially in the historical, compilatory work by Stefan Lukomsky, which appeared in 1770. The peak of the development of this myth is in the well-known Istoriia rusov, a work that was published in the late eighteenth–early nineteenth centuries and which played an immense role in the formation of Ukrainian historical memory and modern Ukrainian historiography.

I will take the liberty of offering a brief quotation about how the leasing of churches by Jews is mentioned in Istoriia rusov: “Churches whose parishioners opposed the union [Union of Brest—Ed.] were leased to Jews, and a cash payment from one to five thalers was established for any services in them.” That is, for the first time there is a concrete sum that Jewish leaseholders supposedly received for granting permission for an Orthodox service. “Jews, as the implacable enemies of Christianity, those universal wanderers, delightedly undertook this kind of disgusting income generation that was so reliable for them, and they immediately took the keys to churches and bell ropes off to their taverns. In connection with all kinds of needs, Christians must now go to the Jew to haggle and, wherever possible with regard to a service, to pay for it, beg for the keys, and the Jew, having laughed aplenty at the divine service and having castigated everything that is revered by Christians, calling it pagan, would command the churchwarden.” In other words, this is the most developed form of the myth, which played absolutely no role during the Khmelnytsky rebellion and emerged later in completely different circumstances and is basically of Polish origin.

Andriy Kobalia: When we talk about the haidamaka movement, we know that very often it was organized by Zaporozhian Cossacks. Jews, Poles, and I understand even [Ukrainian] Greek Catholics were victims. Can one presume that there could have been converted Jewish Cossacks among the haidamakas? Is this possible?

Volodymyr Liubchenko: Yes, this is absolutely possible. If we are talking about the haidamaka movement, which arose in the 1720s and lasted until the 1770s, in some historical documents we come across mentions of converts, some of whom were haidamakas. Nevertheless, it must be noted that, analogously to Ukrainian haidamaka detachments, historians are aware of small bands of socially similar unconverted Jews. We see that, analogously to the Ukrainian haidamakas, there could also have been small Jewish detachments composed of déclassé Jewish elements who were still devoted to their own religion.

Andriy Kobalia: We were speaking with the historian Volodymyr Liubchenko about relations between Jews and the Zaporozhian Sich in the eighteenth century. Andriy Kobalia was at the microphone and this program was made possible by the Canadian non-profit organization Ukrainian Jewish Encounter. Listen. Think.

Originally appeared in Ukrainian (Hromadske Radio podcast) here.

NOTE: The UJE does not necessarily endorse opinions expressed in articles and other materials published on its website and social media pages. Such materials are posted to promote discussion related to Ukrainian-Jewish interactions and relations. The website and social media pages will be places of information that reflect varied viewpoints.