“Zionists” and “Ukrainian bourgeois nationalists”: How they were joked about in the USSR

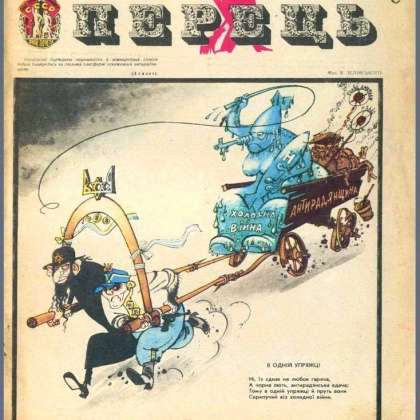

Today we are talking about the specific features of humor in the magazine Perets [Pepper], which often featured themes exploring Ukrainian-Jewish relations in cartoons depicting the interaction between “Zionists” and “Ukrainian bourgeois nationalists.”

Iryna Slavinska: One of the featured events at the Arsenal Book Festival, held from 17 to 21 May 2017, was an exhibition called Kilometr Pertsiu [A Kilometer of Pepper], which was devoted to cartoons and covers of the famous satirical magazine Perets. On this program of Encounters we discuss the specific features of this magazine and topics related to Ukrainian-Jewish relations, which were covered in Perets. At a certain point in its existence the magazine joked a lot about “Zionists,” especially about dissidents and the interaction between so-called “Zionists” and so-called “Ukrainian bourgeois nationalists.” There are several very interesting spreads, images, and even covers devoted to this subject. In our studio we are talking with the culturologist Diana Klochko, the co-curator of the exhibition A Kilometer of Pepper.

Diana Klochko: I, who was born in the early 1960s, simply lived with the idea that this magazine Perets exists. It comes out twice a month, and it is in the village library. It was sold everywhere: in the raion center, the oblast center. It was part of daily life, this magazine. Of course, one could subscribe to Krokodil, the Moscow [satirical] magazine, but for some reason everyone in Ukraine subscribed to Perets. And I never reflected on why this habit suddenly went to the dogs in the 1990s.

Iryna Slavinska: Perets was always in our house. My grandfather subscribed to it. My father bought it regularly. In the 1990s the magazine mostly published jokes about various crises, low salaries, alcoholism, and generally about domestic relationships among people living in the young newly-independent Ukraine. This video and the hand of the authors of Perets are familiar to me, even when I look at issues of Perets from the 1960s, for example.

Diana Klochko: Yes. This merely attests to the fact that certain visual standards were preserved in it. What is most interesting is that they were truly conserved even when the permanent editor left, and he had been there for several decades, since the years. That is, he set the bar high for visual images. I’m not talking about the prerevolutionary Perets, the Kharkiv Perets, the so-called Chervonyi Perets [Red Pepper], in which Dovzhenko and Petrytsky worked as cartoonists. You can imagine the level of artistic talent here.

Pavlo Hudimov, the co-author of this [exhibition] space, and I set out to examine various themes and to select individual, large images. We looked at the magazine as a visual language that had been forgotten, but which had been part of both the Ukrainian mentality and Soviet mentality, Soviet ideologemes, and at the same time a display of a very high level of graphic culture. In other words, there is a minimum of three things that must be considered when you examine this phenomenon. We placed an emphasis on the visual and not the textual, but it must be noted that practically all the Ukrainian satirists in the twentieth century got their start there.

Iryna Slavinska: There were many satiric and ironic texts. In order to continue approaching our topic and helping to acquaint those who don’t know the history very well or are generally unfamiliar with Perets, can it be said that Perets set the standard for Ukrainian humor in the twentieth century? Or can another word be used instead of “standard,” perhaps “an exemplar”?

Diana Klochko: There is a problem here. If you spent time at this exhibition—and I was there every day for several dozen minutes, observing viewers—you would see that very few people were smiling. This demonstrates that this humor, satire, and laughter are often a problem for the contemporary individual. With my smartphone I often even captured the gloomy faces of young people who are trying to grasp and understand what is so funny here.

Iryna Slavinska: Not enough context?

Diana Klochko: Not enough context. What we laugh at has also changed. That is why there is a more complex problem here. On the one hand, we deliberately singled out the topic of “hostile voices.”

Iryna Slavinska: There’s even a microphone inscribed with the words “Radio Liberty,” which embodies that “voice.”

Diana Klochko: Absolutely! There are things here that must be explained to contemporary young people right now, not only about radio jamming but also why next to these microphones there must always be the obligatory Ukrainian bourgeois nationalist wearing an embroidered shirt and sporting a trident. This is fascinating because the work of Ukrainian bourgeois nationalists was part of these “hostile voices.” This was the very voice that was being jammed. But that voice was marked precisely as that of a Ukrainian, although Radio Liberty also broadcast in Russian. But it was marked in Ukraine as Ukrainian, with marks of Ukrainianness.

It is very interesting that they talked about the Soviet world as the absolute norm, and everything else was supposedly a deviation from the norm. That is why, for example, in this ideological caricature—and it was always ideological—there is always the image of [a female] Soviet Ukraine, not simply Ukraine but Soviet Ukraine, a vast, Red—she was always depicted as red—female worker with the marks of the village. She always had some sheaves or bread in her arms. Pictured against the background of this female figure were nasty little men, who supposedly could do harm to her from the broadcast range of Voice of America. In these embroidered shirts they were incomparably small, funny, unpleasant, caricaturized. The ideological subtext was always present here.

Iryna Slavinska: Along with this depiction of archetypal Soviet Ukraine in red tones, there was a category of caricatures and sketches that were more of a domestic nature. For example, there are pages devoted to the topic of corruption, as we call it today; to bribery and not very conscientious work, excessive bureaucracy. This is an interesting spectrum of self-criticism, if it is indeed self-criticism. In the pictures in Perets during the perestroika period, I also remember jokes about new fashions: cloches, long hair.

Diana Klochko: Bohemians.

Iryna Slavinska: Bohemians, and speculators as well. My mother went to the exhibition with me and in the images she could recognize herself as a young student who bought dresses and shoes from speculators as this was one of the only means of getting normal clothes. Can you comment on this? They do not look exactly like enemies of great Soviet Ukraine. These are minor personalities.

Diana Klochko: You mustn’t forget that this was the organ of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Ukraine. And these small personalities attested to this: Communism does not exist in our country yet, but why? Because in our country there are personages that are preventing the advent of the communist future. And, as a rule, all this was connected with the economic factor and collective farms, which were not managed properly, whose income was too large. They put people in prison for this too. And all those who bought foreign-manufactured goods were also regarded as people who were taking money away from the producers of our goods, you understand? In other words, behind all this was also that additional economic component. We cannot be completely happy in the economic sense because we have such wreckers in our country.

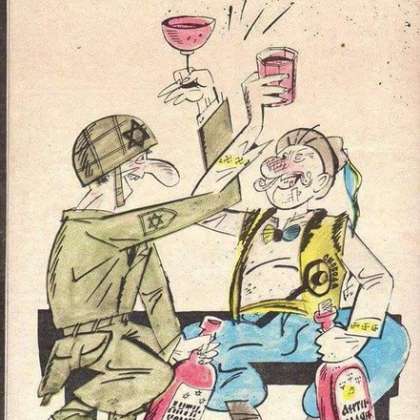

Iryna Slavinska: From this topic we will move on to the topic of how Otherness was depicted in Perets. We can talk about the portrayal of these terrible Ukrainian bourgeois nationalists with mazepynka caps on their heads, with a trident that bears a bit of Narbut’s typeface, I seem to remember. They can be recognized by the very distinctive features of their faces and poses. Alongside this hero, the figure of a “Zionist” appeared regularly in Perets. Either way, I’m talking about the enemies of Soviet Ukraine. So, we can talk about the iconography of both; how they are depicted and why. Afterwards we can reflect on why this pair appears so often in the pages of Perets.

Diana Klochko: Judging by our research—and we looked through magazine issues from the second half of the 1950s, the 1960s mainly, and the 1970s—this pair appears continuously, in fact. In other words, this is a permanent precept, according to which they must appear side by side. Very often they are running—running and panting.

Iryna Slavinska: Or hitched to the same wagon.

Diana Klochko: Or they are laughing at something, guffawing, working together. Two flags may also be depicted next to them. The Ukrainian figure was marked by the trident, and the Zionist—by the Star of David. And they had to be shown holding specific flags, flags that were banned in the USSR. They are depicted as a cozy pair of colleagues; in fact, as friends, colleagues, people who are ideologically close.

Iryna Slavinska: How do we see this? Do we see this in the fact that they are pictured together? How is this friendship interpreted?

Diana Klochko: They are pictured together, that is, they are brothers.

Iryna Slavinska: What are they like? Are they similar to each other?

Diana Klochko: Yes, this is a very interesting question because there are certain archetypal features inherent in both peoples. This is missing here, as a rule. Both one and the other are always vile. Next, there is the archetype of the well-fed Ukrainian with a potbelly, who appears a lot in Perets.

At the same time, a Ukrainian bourgeois nationalist is always dressed in an embroidered shirt. Both the Zionist and the bourgeois nationalist are always thin and dried up. They are—how shall I put it?—sick, physically sick people. They are begging, they are malnourished; they always have a number of physical shortcomings.

This is fascinating because of the other enemies of Soviet Ukraine, for example, a very big, powerful, and stout capitalist, who always has bombs or cigars in his hands, if he’s an American capitalist. He may be wearing a top hat, and a bow tie, not a tie.

And this little pair—“Zionists” and “Ukrainian bourgeois nationalists”—are ferrets or rats, so to speak…. Perets cartoonists made use of many animal metaphors. These enemies seem always to be seriously malnourished…. They look as though they’re on the verge of dying. That’s interesting too, isn’t it? The whole time, for decades, they appear shrivelled like this.

Iryna Slavinska: Yes, and in this context, how can one not recall [the words from Shevchenko’s poem “To Osnovianenko”—Trans.] “It will not die, will not perish” and [the national hymn] “Ukraine has not perished yet.” Of course, this is a kind of retrospective joke, from the perspective of 2017. If all these patterns governing depiction are decoded from the language of images into the language of political and ideological messages that are sent to us, what can be read there?

Diana Klochko: They communicate that in Ukraine, in Soviet Ukraine, there is no money as such because there are practically no instances of financial transactions involving money. It seems not to exist. In the world of [filthy] lucre, as it is called, money exists, which is why dollars are constantly present, specifically the dollar sign; it is constantly present, practically like in Andy Warhol, who turned the dollar sign into a painting. But this is frequently encountered precisely in Ukrainian cartoons.

Iryna Slavinska: And exclusively in a negative sense, yes?

Diana Klochko: Yes, this currency was always present as the chief currency of the capitalist world, although the Euro did not exist at the time; there were very many currencies. That’s the first thing; and the fact that this panting, haggard duo, this little pair needs money. They work for money—big capital, roughly speaking. There was a negative context to this. In my opinion, roughly speaking, this is connected with the rhetoric about “grant-eaters” [People who live off grants but produce nothing—Trans.] because today a lot of hostile things in this visualization have been transformed in our country into words. That which existed at one time in visual images has been seemingly thrown into our subconscious. Just like “Zhydo-Banderites”—that is also a word taken from this picture.

Iryna Slavinska: Yes, in fact it’s a kind of very loaded meme that contains a broad array of ideas, but no longer in the form of depictions but words. Do people in Ukraine today joke the way that Perets jokes or joked? What has changed? What codes and currents have changed?

Diana Klochko: This is precisely what is most fascinating. On the one hand, we did this project in order to show that there is a certain rupture, in which the visual could be transformed into memes, in which the visual culture of the cartoon is destroyed, because right now in our country no one draws like that, not a single publication has such a stable of cartoonists. It must not be forgotten how many of them there were, and they kept appearing and appearing. Furthermore, cartoonists were able to work for other publications.

Iryna Slavinska: At the same time I will comment that in Ukraine the school of caricature has been preserved, and from time to time I see news popping up about international competitions and prizes, where Ukrainian cartoonists traditionally win first place, or place in the top three. In fact, however, this is not at all similar to Perets.

Diana Klochko: Yes. In other words, no periodical with working cartoonists has appeared in our country. A Charlie Hebdo has not emerged in our country, in which new humor would utilize completely different images. To some degree, humor today has become very situational, very fast, because what we were laughing at yesterday on social media sites is no longer relevant today. We laughed one day; now we’re moving on. A publication schedule of twice of month is now too late. Understand? The sense of humor, the speed of humor, and what we find humorous has changed. Don’t forget that in Perets there was absolutely no humor about powerful political figures. Yes, in a few issues we found some references to Truman, or Eisenhower, or somebody like that. But today the majority of caricatures is tied to political discourse.

Iryna Slavinska: Well, now when you bring up names you provoke a lot of associations. If you draw Trump, you immediately have a lot of things in mind. When you draw Putin, you immediately have an entire orbit of meanings. What has changed in contemporary Ukrainian humor in comparison with the humor in Perets? And with the view toward “others”? We can refer our listeners to the program we did about the vertep, and the creation of the comic profile of Jews. Today Ukrainians are also joking about other people, not just about Jews, but other things.

Diana Klochko: Other things. We tried to look for this, but we did not discover how Perets depicted Russians.

Iryna Slavinska: And?

Diana Klochko: There’s a big blank; not a minus sign, just a blank. Because very very few depictions of Russians were found there, and they were not even entirely cartoon images, you understand? Instead, to create an enemy… there are tons of Germans, and this was the very connotation that pertains to fascism. There were hardly any Italians—who were fascists. What was selected and what was not is also interesting. So, for example, to depict a Russian as an enemy now—this cartooning tradition does not exist in our country. It simply does not exist.

Iryna Slavinska: And that’s precisely why the image of fascism, Nazism, which is used as an understandable code, appears time and again.

Diana Klochko: If someone got around to researching this image of the Nazi, the fascist, the German (all three images must be indicated here) in the cartoons published in Perets and how they continue to exist to this day, this would be most interesting. How are they used—granted, somewhat differently—but absolutely used, and deliberately?

Iryna Slavinska: We were speaking today on the program Encounters with the culturologist Diana Klochko, the co-curator of an exhibition devoted to the magazine Perets, on how Soviet Ukraine joked around, the targets of these jokes, and consequently how associative images and profiles were created.

This program was made possible by the Canadian non-profit organization Ukrainian Jewish Encounter.

Originally appeared in Ukrainian (Hromadske Radio podcast) here.

Translated from the Ukrainian by Marta D. Olynyk.

Edited by Peter Bejger.

NOTE: The UJE does not necessarily endorse opinions expressed in articles and other materials published on its website and social media pages. Such materials are posted to promote discussion related to Ukrainian-Jewish interactions and relations. The website and social media pages will be places of information that reflect varied viewpoints.