The tradition of mutual influence in the cultures of humankind is immense, and we do not know much about it: Leonid Finberg

A conversation about new books published by Dukh i Litera

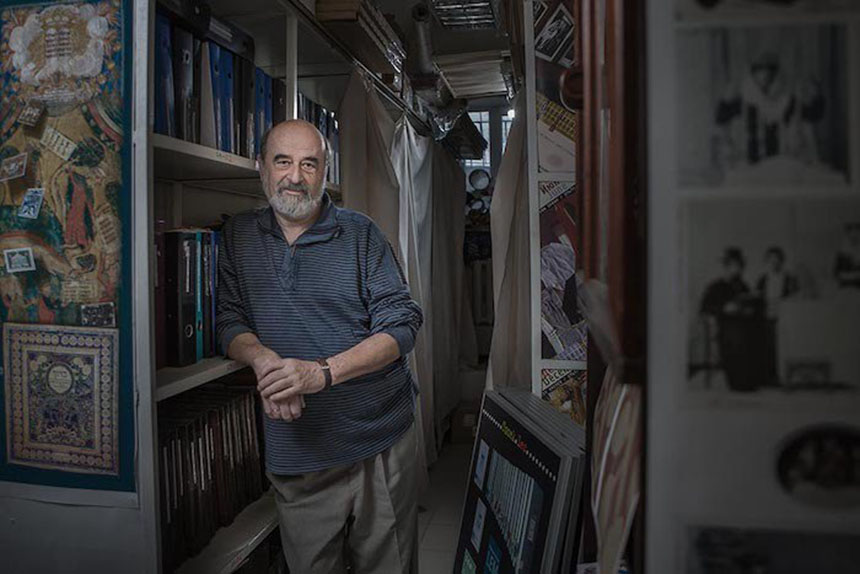

Our guest on today’s show is Leonid Finberg, director of the Center for the Studies of History and Culture of East European Jewry and editor in chief of the Dukh i Litera Publishing House.

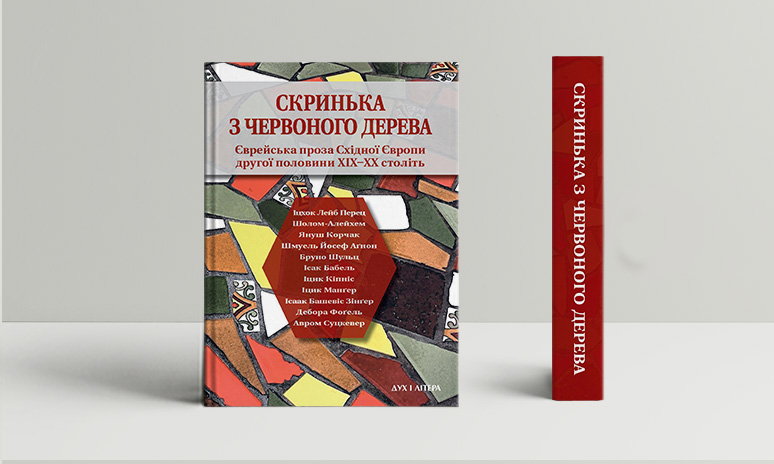

Vasyl Shandro: A recent publication is Mahogany Chest: Jewish Prose of Eastern Europe, Second Half of the Nineteenth–Twentieth Centuries. How worthwhile is it to include such different authors from various eras and countries within the covers of a single book?

Leonid Finberg: Every matter has its pluses and minuses. We began publishing books thirty years ago, but we learned how to do this twenty years ago. There is no great need to talk about Soviet traditions. Over this period of time, we had to catch up with other countries and cultures where there were no tragedies like we had: the Holodomor, revolutions, the Holocaust, and Stalinist repressions. It was necessary to start reading as quickly as possible the things that the world was reading. In this regard, we, as publishers, enjoyed certain advantages. We were positioned on such an open field, where we could choose much more than our colleagues in Poland or Germany. In those countries, almost everything has been published, and they are monitoring new things that have appeared. For us, what is new is practically the entire huge culture of the twentieth century, from the beginning to the present day. It is not so simple to carry out this task. For myself, I decided that anthologies are an excellent way to present various phenomena. We already have the experience of publishing anthologies of texts about the Ukrainian dissident movement. The book sold out and we have now published it in English; it has spread across the world.

We also wanted to publish and present Jewish literature since I head the Center for the Studies of History and Culture of East European Jewry. When we began to look closely at what exists, we found anthologies that were published in the United States, which has a mighty corpus of Jewish literature. I wanted to combine authors whom we had already translated within the covers of a single book. The Dutch Jewish Humanitarian Fund supported this idea and offered us an opportunity. We would like to publish a multivolume library consisting of separate volumes devoted to each of the writers whom we have presented. I hope that this will be done by our children and grandchildren after acquainting themselves with the masterpieces that we are presenting.

Vasyl Shandro: The anthology features very different authors and texts from various territories. What picture is generally formed? What does an anthology like this talk about?

Leonid Finberg: Owing to clear and well-known reasons, Jews were resettled in various countries across the world. In many of these countries, they became part of those cultures among whom they lived, and some of them continued the great tradition of Jewish spiritual thought to which they belonged. This is precisely the reason why we wanted to collect and present this within the covers of a single book. When we did this, I was glad because we had come up with this. The names of Sholem Aleichem, Korczak, Agnon, Bruno Schultz, [Isaac] Babel, [Isaac Bashevis] Singer represent high European culture mostly of the twentieth century.

Vasyl Shandro: In regard to the nineteenth century, are there enough secular texts there?

Leonid Finberg: No, I think that in our lands, this part of Europe and the world, it was just being born as Yiddish-language literature. Writers championed the idea that this language is not jargon, is not something secondary; they were struggling for their place in the sun. Two years ago, we held a conference pegged to the 110th anniversary of the conference that established Yiddish as a full-fledged language of a culture. This did not exist earlier; for the most part, there were texts written in Hebrew or the languages of the peoples among whom Jews lived. It is interesting that this conference took place in Chernivtsi, and the Jewish writers and figures did not admit those who had organized this conference. It took place at the Ukrainian Home. This literature subsequently blossomed, and, in my opinion, it is one of the most interesting literatures of the early twentieth century.

As a publisher, I have set myself the task of translating as many texts as possible into Ukrainian, just like they exist in the majority of countries and nations throughout the world—translated into German, French, Russian, and Polish. I hope that we, too, will do this and that these texts will enter Ukrainian culture, all the more so as most of them were written in our lands. One way or another, this topic is often Ukrainian–Jewish, Polish–Jewish, and Russian–Jewish.

Vasyl Shandro: Where Jewish literature on the territory of Ukraine is concerned, was this in spite of or no thanks to?

Leonid Finberg: It’s difficult to say. Often it was in spite of. I can quote Yosef Agnon (S.Y. Agnon, ed.), who wrote: “Who were my teachers in poetry and prose? That is a controversial question. In my books, some people notice the influence of writers of whom I have never heard. Above all, the Holy Scriptures—they taught me how to form letters. Then the Mishnah and the Talmud, the Midrashim and Rashi’s interpretations of the Torah. Then Judges and our holy poets, the wise men of the Middle Ages and, above all, our Rambam, blessed be his memory. After I mastered the Latin alphabet, I read in German everything that I came across and, of course, I found there what resonated in my heart.”

So, I am talking about a synthesis, the mutual influence of these cultures and literatures. At one time, we published a two-volume work entitled Jewish Civilization. This is a thousand-page Oxford textbook. I was absolutely struck by the influence of Islam on Judaism and Judaism on Islam during the Middle Ages. The tradition of mutual influence in the cultures of humankind is immense, and we do not know much about it.

Perhaps once we familiarize ourselves with these texts, we will return to them, but at the present time, I do not know of a single researcher who could write about this. With the passage of several generations that have ripped us from the roots of culture, from languages, from the possibility to engage in literature and scholarship, it is very difficult to restore this later. When we began, we did not even have teachers. They were Israeli or French academics whom we knew; ours had been killed in the Holocaust or had ended up in the GULAG. Today we can also talk about certain achievements.

Vasyl Shandro: How does one discuss Ukrainian–Jewish relations so as to avoid interethnic, intercultural conflicts?

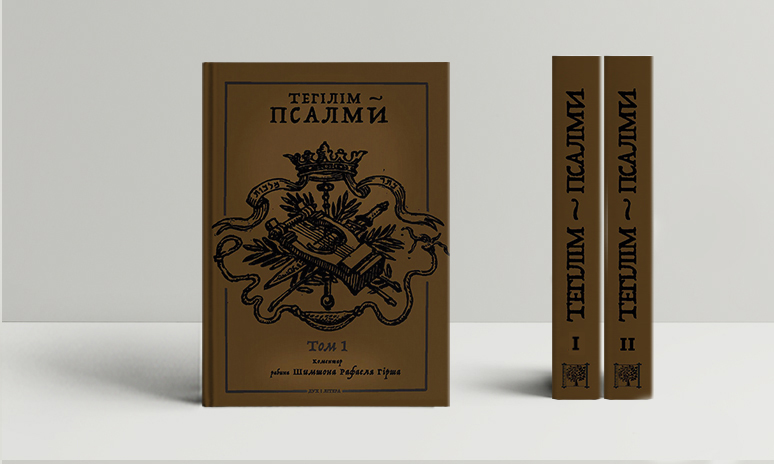

Leonid Finberg: As is the case with all other dialogues and contradictions that have existed throughout history, we must orient ourselves on the crucial need to understand not only ourselves but the other. Recently a ZOOM conference took place, during which we launched our new publication Tehilim: The Psalms of David, which includes the commentaries of Rabbi Samson Hirsch. These are a thousand pages of text and absolutely brilliant commentaries not only on each psalm but also each phrase of each psalm. The work on this book lasted seven years, and we prepared it in such a way that it is becoming the foundation of dialogue and interest among Jews, Christians, and Muslims.

It is emblematic that this book was written by a rabbi, and the foreword was written by a priest [Archbishop] Borys Gudziak. Thus, the Jewish and Christian traditions met in this book. I think that we are talking about the richness of the Judeo-Christian civilization. Christians know that the lion’s share of the texts of Christianity are Bible texts, Torah texts. Our conversation was built precisely on this, and I think it has been successful.

I understand that there are people who are fixated on contradictions and pain. They cannot be silent, but we understand not only our own pains, but we also understand the pains of our neighbors, friends, colleagues—even our enemies.

This anthology is a synthesis of Jewish and Ukrainian cultures. I enumerated the giants of Jewish culture who are featured in the book, but the Ukrainian translators are also very gifted. In my opinion, we learned how to do translations on a very high level, which was nearly impossible earlier. The exceptions are the translation geniuses Lukash and Moskalenko, who preserved Ukrainian culture during the dark Soviet period. I think that this dialogue proceeds not only through text but also contexts because this is a dialogue of two languages.

Vasyl Shandro: What are the genres of these texts?

Leonid Finberg: For the most part, this is high prose. Thank God we were able to select the finest examples of this kind of prose. For example, we selected the Bruno Schultz texts from among four translations that exist in Ukrainian culture. It was difficult to select the finest texts of Janusz Korczak. Thanks to his texts, part of international law—children’s rights—was defined. We have brilliant translations by Oleksandr Irvanets and Volodymyr Kadeniuk. The book begins with the translations of Mykola Zerov; he translated Yitskhok Leybush Peretz.

This is another topic that awaits its researcher. During the Soviet period, mendacious stereotypes of people’s hatred of each other were imposed on us; they spoke of the hostility of people from various nations, not just Jews and Ukrainians. Right now, we are trying to find and describe how translations were done from the Yiddish into Ukrainian, as well as from the Ukrainian into Yiddish. This is despite all the prohibitions. There is a wonderful study featuring articles by Ola Hnatiuk, who wrote that after the war, both Ukrainian and Jewish writers were forbidden to write about the Shoah, the Holocaust. The Soviet discourse needed false heroes. This entire history needs to be rewritten. I think that we are on the right track, and step by step, we are publishing these books.

In order to write the history of Georgia, Stalin killed off practically the entire intelligentsia of the country. The same thing happened at the beginning of the twentieth century. This definitely applies to the Second World War. Right now, the Russians are constructing their own discourse, casting themselves as victors. We have heard so many stupidities about this from Putin and his henchmen. These are all lies. Truth is not on their side, and I am certain that truth will win.

For the full program, listen to the audio file (in Ukrainian).

This program is created with the support of Ukrainian Jewish Encounter (UJE), a Canadian charitable non-profit organization.

Originally appeared in Ukrainian (Hromadske Radio podcast) here.

Translated from the Ukrainian by Marta D. Olynyk.

Edited by Peter Bejger.

NOTE: UJE does not necessarily endorse opinions expressed in articles and other materials published on its website and social media pages. Such materials are posted to promote discussion related to Ukrainian-Jewish interactions and relations. The website and social media pages will be places of information that reflect varied viewpoints.