Architect Lev Weingort, Savior of Poltava

Many Ukrainian cities are experiencing a construction boom today. New highrise buildings, residential complexes and entire microdistricts are changing their habitual appearance. And quite often — not for the better. We are already accustomed to scandals and protests associated with urban construction.

Ukrainian society is just learning to defend its interests, in this case — to create or maintain a comfortable living environment. We want to live in cities that keep their history. Where business interests find a compromise with the desire of citizens to live in an aesthetically and environmentally friendly urban environment. And all this must be provided to us by city officials and architects, who create the Ukrainian cities of the future with their own hands. Therefore, it is important for us turn to the experience of the Ukrainian architects of the past generation who, despite the ideological and bureaucratic difficulties of the Soviet era, were able to save or rebuild after the war beautiful Kyiv, Odessa, Lviv and many other cities of Ukraine.

This article, written by Vadim Goloperov, appeared in the October/November 2017 issue of The Odessa Review, which was supported by the Ukrainian Jewish Encounter.

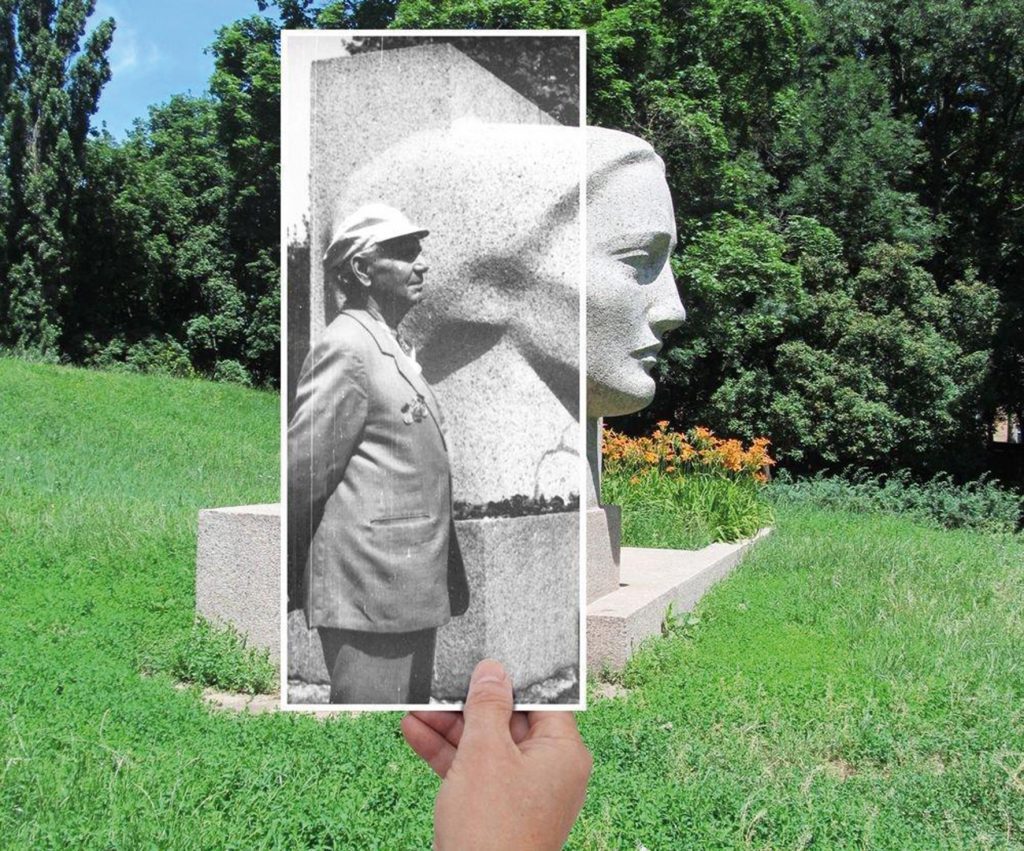

One such outstanding Ukrainian architect was Lev Semenovich Weingort. He was born in Warsaw in 1912 in a Jewish family, and at birth was named Aria Leon, but soon moved to the Ukrainian city of Poltava. In 1938, Weingort graduated from the Kharkiv Institute of Civil Engineering, worked on the construction of the Moscow Metro, then returned to Poltava. It should be noted that Poltava is a special city for Ukrainians, it played a big role in the formation of the Ukrainian ethnos, Ukrainian culture, and Ukrainian folklore. When the young Weingort, was unexpectedly appointed the chief architect of Poltava, he did not succumb to the futurist and constructivist trends in architecture, the Soviet aspiration “to destroy everything above the ground”, but instead immediately showed himself to be a supporter of preserving the history of his native city. As Weingort said, the main principle of architects and doctors is to “do no harm”. Returning to Poltava after it was abandoned in 1943 by retreating German troops, he found a terrible picture: 80% of the housing stock, 100% of cultural and administrative buildings, and 100% of industrial buildings were destroyed. Weingort managed the clearing of the ruins, and one of his first major projects was the central square of the city. The chief architect managed to persuade the city and the Ukrainian Soviet Republic authorities to restore the unique architectural complex of the Round Square in the style of classicism that had taken shape in the 19th century, rather than creating an ensemble of buildings typical for many Soviet cities. The plan for the restoration of the square was realized in the 1950-60’s, and today it is one of the main attractions of Poltava. As the chief architect, Lev Weingort also decided to take industrial enterprises out of the center, to the railway station. He planned residential microdistricts, and supervised the construction of a bridge over the Vorskla river. Weingort understood the importance of having parks and other green areas in the city, thanks to him Poltava became home to one of the best dendrological parks in Ukraine.

We can get a glimpse of the chief architect’s daily work by reading his memoirs, “Notes of the Provincial Architect”, in which there are many comical episodes. Once, he had no choice but to put a monument of Stalin on top of concrete sewer rings: there simply was no other material available. The chief architect was greatly relieved when, following the condemnation of the Stalin cult in 1956, this monument was condemned and urgently removed in the night. There was another funny episode, connected with the Soviet “leader of the nations”. In 1939, on the eve of the anniversary of the October Revolution, the architect prepared a festive decoration of the city. It’s main element was a huge panel with a portrait and a well-known saying of comrade Stalin’s: “We do not want war, but if we have to fight, then in a foreign territory”. And suddenly the authorities, found a strange inscription at the bottom — “NepyiPivo” (“Do not drink beer” in Ukrainian). After the scandal and proceedings it became clear that this was the surname of the artist, the author of the panel. In 1939, it could have ended badly, but luckily everything turned out fine.

Weingort often had to settle disputes between Poltava’s citizens. The residents of one building complained that their upstairs neighbors kept a pig on their balcony, and dirt/mud from this makeshift sty kept dripping down into their apartment. The fact was that after the war there was a shortage of food in the city, so people would keep animals at home. The chief architect solved this problem with an abundance of tact. That the pig belonged to a famous actress of the Poltava Theater and her husband, the theater’s chief director, probably encouraged a diplomatic approach. It was decided to equip the balcony with a solid metal box in the form of a huge bath, and arrange a mobile pallet on the bottom to remove waste, thus containing the pig. In autumn, the artists invited the chief architect and the mayor to visit them for a ham from a balcony-raised pig.

In this treasury of curiosities we also find a complaint about a cart in which carbonated water was sold on one of the main streets of the city. Dirty and drunken people would often gather around it. For some reason no one could get it removed. It turned out that alcohol was mixed in the water, and city officials working in the neighboring building were regular customers. These are the sorts of problems the chief architect of Poltava had to face over the years.

At the same time, based on his experience, he outlined the perennial conflict between architects and governments. “The conflict of architects with authority is objective. With, I want to emphasize, any authority. Such a specific art … The trouble is, if the authority is ambitious, opportunistic, conjectural or, God forbid, corrupt or overly ideologized”. Many of Weingort’s designs were rejected, for his desire to preserve the ancient churches he was called “archimandrite” instead of architect.

Besides the revival of the ruined Poltava, Lev Weingort managed to complete another important project in his life: the recreation of the home of the great Ukrainian writer Nikolai Gogol in the Poltava region, which was destroyed by the Nazis in 1943. It is known that Weingort with love related to the work of Gogol. He liked to quote the words of the writer: “Architecture is also a chronicle of the world, it speaks when both songs and traditions are silent”. The work was started in 1968, the estate was restored according to old photographs and drawings, memories of friends who were in this house. And most of all helped by Gogol himself. He loved his ancestral estate, and often in letters to his mother gave detailed instructions on what to do with it and how. After the family house of the Ukrainian writer was restored, for about ten years Lev Weingort was the director of the Gogol museum in the village of Vasilievka in the Dikanka district of the Poltava region.

Before his death in 1994, Lev Semyonovich developed an interest researching Jewish cultural buildings in Poltava. He looked for places where there had been a soldiers’ synagogue, or a merchants’ synagogue. He began collecting information for an article on the traces of Jewish culture within Ukrainian culture. Of course, in Soviet times he could not have done this. In his memoir “Notes of a Provincial Architect” he recalls how in 1953 an attempt was made to dismiss him for being a “cosmopolitan Jew”. And in 1970 the management unexpectedly accused Weingort of giving the grieving woman on the monument to the victims of fascism, which he supervised, a Jewish face in a deliberate attempt to make the monument exclusively Jewish. This was a ridiculous accusation against a man who grew up in Ukraine, was married to a Ukrainian, and honored the memory of all people, regardless of nationality, who suffered from fascism.

This is the mark left on history and architecture by Lev Semenovich Weingort. He liked tell his students that it is difficult for an architect to hide his mistakes, because they are visible to everyone and will be visible for a very long time after his death. And this should be remembered by the architects of future generations.

NOTE: The UJE does not necessarily endorse opinions expressed in articles and other materials published on its website and social media pages. Such materials are posted to promote discussion related to Ukrainian-Jewish interactions and relations. The website and social media pages will be places of information that reflect varied viewpoints.