Chapter 10.1: "Jews and Ukrainians: A Millennium of Co-Existence"

Jews and Ukrainians: A Millennium of Co-Existence is an award-winning book that explores the relationship between two of Ukraine’s most historically significant peoples over the centuries.

In its second edition, the book tells the story of Ukrainians and Jews in twelve thematic chapters. Among the themes discussed are geography, history, economic life, traditional culture, religion, language and publications, literature and theater, architecture and art, music, the diaspora, and contemporary Ukraine before Russia’s criminal invasion of the country in 2022.

The book addresses many of the distorted stereotypes, misperceptions, and biases that Ukrainians and Jews have had of each other and sheds new light on highly controversial moments of Ukrainian-Jewish relations. It argues that the historical experience in Ukraine not only divided ethnic Ukrainians and Jews but also brought them together.

The narrative is enhanced by 335 full-color illustrations, 29 maps, and several text inserts that explain specific phenomena or address controversial issues.

The volume is co-authored by Paul Robert Magocsi, Chair of Ukrainian Studies at the University of Toronto, and Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern, Crown Family Professor of Jewish Studies and Professor of History at Northwestern University. The Ukrainian Jewish Encounter sponsored the publication with the support of the Government of Canada.

In keeping with a long literary tradition, UJE will serialize Jews and Ukrainians: A Millennium of Co-Existence over the next several months. Each week, we will present a segment from the book, hoping that readers will learn more about the fascinating land of Ukraine and how ethnic Ukrainians co-existed with their Jewish neighbors. We believe this knowledge will help counter false narratives about Ukraine, fueled by Russian propaganda, that are still too prevalent globally today.

Chapter 10.1

Diaspora

Since Ukraine is, and has been, a country of many nationalities, it follows that there is not a single Ukrainian diaspora, but rather Ukrainian diasporas, or diasporas from Ukraine. Among those diasporas, some of whose ancestors left the present-day territory of Ukraine, are groups such as the Mennonites in Canada, Crimean Tatars in Turkey, Carpatho-Rusyns in the United States, Russians in Israel, and the main subjects of this book, ethnic Ukrainians and Jews.

At present, there are an estimated 6.1 million ethnic Ukrainians (hereafter: Ukrainians) living in virtually every habitable continent, except Africa. The largest numbers are in Asia, specifically in Russia and in several Central Asian republics. In North America, Ukrainians are somewhat smaller in numerical size, with the most organized diasporan/immigrant communities located in Canada (1.1 million) and the United States (893,000). It is the immigration to North America and Israel that will be the focus of attention in this chapter.

Main centers of Ukrainian immigration

Ethnic Ukrainians began immigrating in large numbers to the United States (from the 1880s) and to Canada (from the 1890s) in a relatively steady flow which lasted until the outbreak of World War I in 1914. Subsequent immigration was interrupted, either by external events (two world wars, 1914–1918 and 1939–1945) or by restrictions imposed by the countries of origin (the Russian Empire, the Soviet Union, and its Communist satellite countries) and by the receiving countries (in particular the United States after 1924). Hence, it is common to speak of various waves of Ukrainian immigration to North America.

Ethnic Ukrainians began immigrating in large numbers to the United States (from the 1880s) and to Canada (from the 1890s) in a relatively steady flow which lasted until the outbreak of World War I in 1914. Subsequent immigration was interrupted, either by external events (two world wars, 1914–1918 and 1939–1945) or by restrictions imposed by the countries of origin (the Russian Empire, the Soviet Union, and its Communist satellite countries) and by the receiving countries (in particular the United States after 1924). Hence, it is common to speak of various waves of Ukrainian immigration to North America.

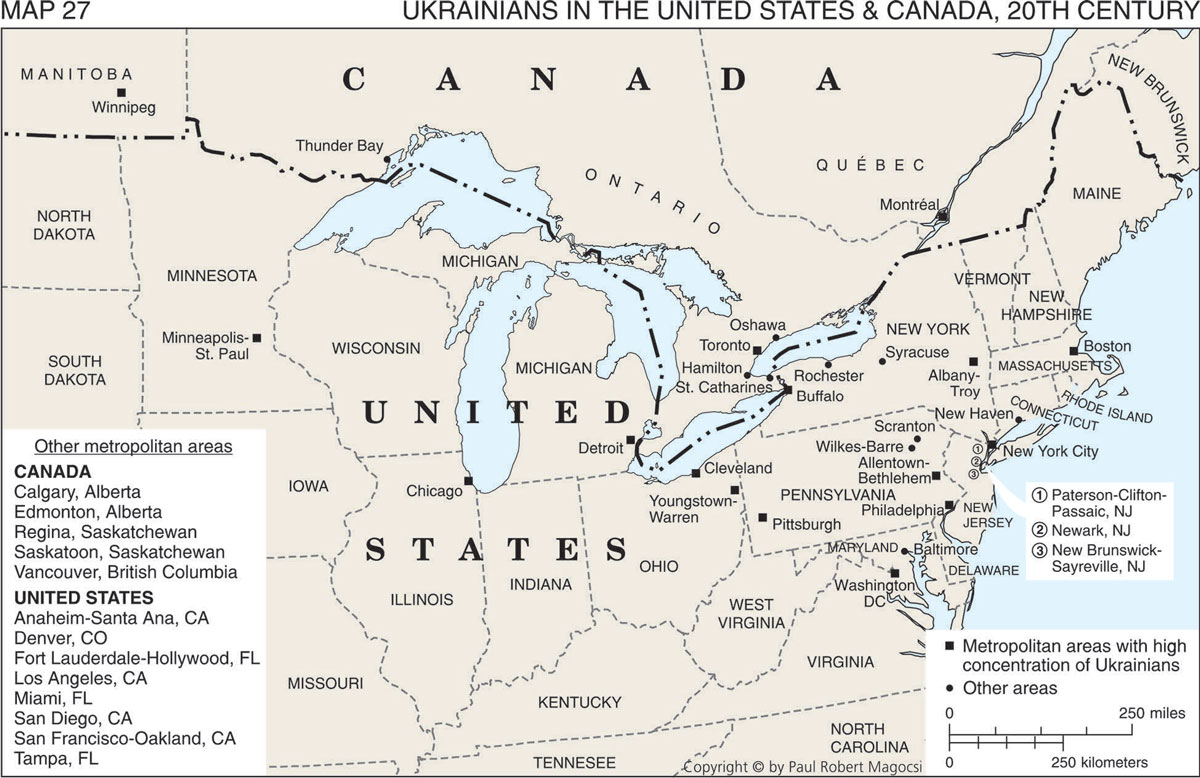

Settlement patterns

The first wave, lasting from the 1880s to the outbreak of World War I in 1914, was numerically the largest, bringing 250,000 people to the United States and 170,000 to Canada. This wave also set the pattern of settlement, which to this day includes areas with the highest concentration of Ukrainian Americans and Ukrainian Canadians: the former industrial belt of the northeast and north-central United States (New York, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Michigan, Ohio, Illinois) and the prairie provinces of Canada (Manitoba, Alberta, Saskatchewan). Because of restrictions imposed by the Russian Empire against emigration, the vast majority of immigrants during the first wave from Ukraine came from what was then the Austro-Hungarian Empire, in particular the Austrian provinces of Galicia and Bukovina, where they were known as Ruthenians. The Hungarian part of the empire, especially several counties in the northeastern part of the kingdom, were also a source of large-scale Ruthenian immigration, most especially to the United States. These people, however, quickly evolved into a Carpatho-Rusyn immigrant community that was quite distinct from the Ruthenians of Galicia and Bukovina who formed the core of what became known as Ukrainians.

The first wave of Ruthenian/Ukrainian immigrants who went to the United States settled primarily in urban areas, where most found employment in coal mines, factories, and various service industries. By contrast, those who went to Canada were encouraged by that country's authorities to settle on the land, in the hope (which was realized) that they would help transform the prairies into arable farmland. Well-defined colonies, or so-called bloc settlements, were established in rural areas of Manitoba and Saskatchewan. There Ukrainians gradually became the numerically dominant population, so that in rural villages it was not uncommon for their language to serve as the medium of public discourse (lingua franca) even for the non-Ukrainians living in their midst.

After the interruption of World War I, Ukrainian immigration resumed in the 1920s, but because of U.S. restrictive quotas (1921 and 1924) most newcomers (68,000) went to Canada. As before the war, the vast majority of immigrants during the interwar years were from western Ukrainian lands, in particular from what was by then Polish-ruled Galicia, and most headed for the bloc settlements that already existed in the prairie provinces.

The outbreak of World War II in 1939 brought Ukrainian immigration to a virtual halt. When it finally resumed toward the end of the war, the characteristics of what constituted the third wave as well as the attitudes of the receiving countries differed substantially from the two earlier periods. The immigrants themselves were refugees either from the war or from the advance of Soviet rule, which, after 1945, extended directly into Soviet-ruled east Galicia, northern Bukovina, and Transcarpathia, as well as indirectly through pro-Soviet Communist regimes into neighboring post-war Poland, Czechoslovakia, and Romania, each of which still included Ukrainian minority populations within its borders.

The post-World War II newcomers to the United States (85,000) and Canada (34,000) differed from their predecessors in two ways. Unlike the previous waves of immigrants, who for the most part came because of the economic hardships they faced at home, the third wave consisted largely of educated professionals from urban areas of all parts of Ukraine — Soviet Ukraine as well as former Polish-ruled Galicia — who either had been brought to Nazi Germany (and Austria) as forced laborers from the east (Ostarbeiter) during the war or who had fled before the advance of the Soviet Army. Many were former political and civic activists of anti-Soviet persuasion, religious figures, or police personnel, soldiers, and partisans who were engaged by the wartime Nazi German regime or who had fought against it. Stranded in refugee camps in the western zones of post-war Germany, they were declared Displaced Persons (DPs), on the basis of which they were allowed entry into the United States and Canada in the late 1940s and early 1950s. This third wave of refugee immigrants settled mostly in the already existing Ukrainian communities in the northeastern United States. Those who went to Canada did not, as before, settle in the western prairies, but rather in urban centers in southern Ontario, most especially Toronto.

Stringent restrictions against emigration to the "capitalist West" put in place by the Soviet Union and its central European satellites virtually cut off all Ukrainian immigration for the next nearly four decades. Finally, a fourth wave began to make its way to North America, initially in small numbers from Poland during the 1980s, then in greater numbers from independent Ukraine from the 1990s to the present.

Fourth-wave Ukrainian immigrants have gravitated primarily to urban areas in the northeastern United States and to the province of Ontario in Canada. They are for the most part highly educated professionals, although before coming to North America they had almost all lived and been acculturated in authoritarian states, where until 1989–91 a person's socio-economic status was determined less by individual initiative than by the dictates of Communist-ruled governments. The Soviet experience and cultural values have not only made it difficult for the fourth wave to integrate into existing Ukrainian diaspora organizations, they have also made adjustment to individualistic-oriented American and Canadian societies quite challenging.

A little known phenomenon is the presence of ethnic Ukrainians in Israel. They are part of the large wave of citizens of Ukraine — over 350,000 — who since the early 1990s have emigrated to Israel. The vast majority are of Jewish ancestry, although about 35,000 are ethnic Ukrainians married to (or the children of) a Jewish partner who decided to emigrate and to live permanently in Israel. There are as well perhaps as many 50,000 of mixed Jewish and non-Jewish Slavic parentage.

Those who are of mixed background are likely to define the Slavic component of their identity as Russian rather than Ukrainian. As for the ethnic Ukrainian immigrants, most have found jobs in factories and in the service industry, and they tend to reside in Israel's smaller cities and towns: Rishon LeZion, Ashdod, Haifa, and Beer Sheva, among others.

Civic and cultural life

The Ukrainian diaspora in North America may be viewed from the perspective of an evolutionary process consisting of two basic stages. The initial stage, which coincided with the first wave of immigration (1880s–1914), was characterized by a struggle to define one's national identity. In a sense, Ukrainians were "made in America" and Canada. This is because when the immigrants first arrived from western Ukrainian lands, then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, they called themselves Rusyns, or in English, Ruthenians, with little or no sense of being Ukrainian. They had to learn this from some of their more nationally conscious secular and religious leaders through participation in secular and religious community functions.

During this identity-formation process, Ruthenian immigrants from the same homeland region, from the same village, and at times even from the same family may have adopted a Ukrainian identity, while others did not. It is for this reason that still today in the United States and to a lesser degree in Canada one may encounter descendants of pre-World War I Ruthenian immigrants from western Ukraine who consider themselves either Russians or Carpatho-Rusyns, but not Ukrainians.

Just how did a portion of Ruthenian immigrants become nationally conscious Ukrainians? This was largely the result of the educational and cultural work carried out by a wide range of organizations founded — and funded — by the immigrants themselves. Initially, the most important of these were mutual-benefit fraternal societies, such as the Ruthenian, later Ukrainian, National Association in the United States (est. 1894) and hundreds of reading halls (chytalni) and enlightenment (Prosvita) circles scattered throughout the bloc settlements in western Canada. These and other organizations founded before and after World War I — including the numerous leftist-oriented workers' halls in Canada — sponsored a wide range of cultural events, set up language classes, and published newspapers, magazines, and books, all with the purpose of raising awareness of Ukrainian national identity and knowledge of the Ukrainian language. In Canada's prairie provinces these tasks were enhanced among young people through the educational system, which provided bilingual Ukrainian and English classes in some provincially run schools before the 1920s and in Catholic parochial schools (during the week or on Saturdays) both before and after that date.

The next phase in Ukrainian community life began in the 1920s, and in many ways it continues to the present. Aware of their Ukrainian identity, community organizations and leaders set out to make their ancestral homeland known to the larger host society, whether the United States or Canada. The events of the Ukrainian revolutionary era (1917–20) and efforts to create an independent Ukraine had a twofold impact on the North American immigration. On the one hand, the political struggle in the homeland helped to cement awareness of and galvanize pride in one's identity as a Ukrainian. On the other hand, the North American communities became divided between different political orientations derived from the homeland, with nationalists, socialists, communists, and monarchists competing for the loyalty and support of Ukrainian immigrants and their descendants.

With the arrival of highly nationally conscious scholars and other professionals after World War II, North American community life was given a new infusion of intellectual energy. A whole host of scholarly institutions that were ideologically transformed or banned outright by the Soviets in the homeland were revived in North America, such as the Ukrainian Free Academy of Sciences in Canada (est. 1949), the Ukrainian Academy of Arts and Sciences in the United States (est. 1950), and the Shevchenko Scientific Society in both countries (est. 1947). The recently arrived scholars formed a pool of qualified specialists, some of whom were engaged by North American universities to teach courses in Ukrainian language and literature, most especially in Canada (universities of Manitoba, Alberta, Saskatchewan, Toronto), or to staff the many university and public libraries that were increasing their holdings on subjects dealing with the West's Cold War rival, the Soviet Union. Then, in the 1970s, research institutes and professorships in Ukrainian subjects were established at Harvard University in the United States and at the University of Alberta and University of Toronto in Canada.

All these institutions helped to raise awareness in the larger American and Canadian societies that Ukrainians were a distinct people with a culture worthy of study. Among the best-known achievements was making the larger public aware of the Great Famine/Holodomor of 1933. On the occasion of the fiftieth anniversary of that tragic event (at the time not recognized by the Soviet authorities even to have happened), the Ukrainian program at Harvard University launched a series of publications and scholarly conferences that were repeated, in part, at other North American universities with Ukrainian programs. As a result, the Holodomor was eventually accepted as a fact by most scholars, and by the outset of the twenty-first century it was being commemorated annually by many cities, states, provinces, and even the federal government as a historic act of genocide against the Ukrainian people.

Religious life

Despite the role of secular institutions, it is religion and the church that have played the major role in sustaining a sense of Ukrainian community cohesiveness in North America. This was certainly the case during the first wave of Ukrainian immigration before World War I. At that time the church was the only institution where, in an otherwise alien North American environment, an individual could find spiritual comfort as well as a sense of familiarity and psychological solace through interaction with other people who spoke the same language and had similar cultural values. Church buildings, therefore, not only had sanctuaries for worship, they also provided access to "basement halls" for social and cultural activities, which might include banquets, theatrical performances, elementary school classes, and meeting rooms for a wide variety of adult and youth activity.

As the immigrant communities grew in size and as their members improved their overall social and economic status, so too did larger church buildings appear. Sometimes former Protestant churches were acquired and restored fully on the inside and partially on the outside; more often new churches were constructed based on models from Europe. The "Ukrainian" church in any North American town or city (which may have been described by outsiders as "Russian") was clearly visible because of its distinct domes and cupolas topped by three-barred crosses and sometimes glittering gilded mosaics on parts of the façade. Consequently, going to church was for the immigrants and their descendants like "going to Ukraine," since the church building, if only vicariously, recreated their ancestral home in North America.

Even for the passive believer or non-believer, the church has been — and remains to this day — the place where most individuals are able to feel that their Ukrainianness is expressed and reinforced. And, while it is certainly true that for many Ukrainians going to church on a weekly basis is rare, Christmas and Easter are quite another matter. Attendance at services on those holidays is considered an important means to assert publicly one's Ukrainian identity in North America.

The church as an institution has not always fared well in North America. In many ways, it has been an institution under siege. This was the result of conditions in both North America and the homeland. In effect, the denominational distinctions that exist in North America today reflect the situation in the homeland, where the vast majority of ethnic Ukrainians are Eastern-rite Christians (either Orthodox or Greek Catholic), with smaller numbers belonging to various Protestant groups. When the first wave of Ruthenian immigrants arrived before World War I from western Ukrainian lands within the Austro-Hungarian Empire, by far the largest number were Greek Catholics from that empire's regions of Galicia and Transcarpathia; the smaller numbers who came from Austrian Bukovina were Orthodox. Ruthenian Greek Catholics were not welcomed, however, by the larger Catholic Church structure of which they were a part. Bishops and priests who comprised the Roman Catholic hierarchy in North America almost without exception knew nothing about the Eastern-rite faithful within their "own" universal church. Therefore, when Roman Catholics encountered in their midst these ostensibly strange people, who followed a different Catholic rite and used an unfamiliar language (Church Slavonic, not Latin) written in an unreadable alphabet and whose priests were married with wives and children, they were aghast. Catholic Church rules not only required priests to be celibate, they also required that every priest in a given diocese be subordinate to the ruling bishop of the given diocese. Initially, Roman Catholic bishops in both the United States and Canada refused to recognize Ruthenian Greek Catholic priests, who were banned from administering the sacraments (baptism, communion) and even from burying their community's dead in Catholic cemeteries. In short, Ruthenian Greek Catholics in North America were outcasts in their own Catholic Church.

Priests and lay parishioners who refused to abide by the demands of the Roman Catholic authorities expressed their displeasure by joining the only other Eastern-rite church in their midst — the Orthodox. In North America, this meant the Russian Orthodox Church, which soon grew rapidly because of an influx of Ruthenian Greek Catholics from the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Some Greek Catholics simply remained in local Roman Catholic parishes that they may have been attending (in particular those with large numbers of Poles and Slovaks). Yet others, as in the case of those living in the Canadian prairie bloc settlements, were convinced by missionaries to join Protestant churches, or even a unique Protestant form of Eastern-rite Christianity "made-in-Canada" — the Independent Greek Church.

Although the status of Greek Catholics gradually improved (they received their own bishop in 1908 in the United States and in 1912 in Canada), the siege mentality was to continue. This time the reason was the political upheavals in the homeland, where, following the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917, churches that were specifically Ukrainian in orientation were discriminated against and eventually outlawed in Soviet Ukraine. These included the Ukrainian Autocephalous Orthodox Church in 1930 in eastern Ukraine and the Greek Catholic Church in 1946/1949 in western Ukraine.

As a result of Soviet repression, Ukrainian-oriented churches could survive only in the diaspora. The largest parishes among diaspora Ukrainian Catholics (the new post-World War II name for Greek Catholics) and Orthodox were in North America, with the seat of the Ukrainian Autocephalous Orthodox Church and its hierarchy actually located in the United States (Bound Brook, New Jersey). Both churches received an influx of members as a result of the post-World War II third-wave immigrants and their descendants. In former Austrian and Polish-ruled Galicia, the Greek Catholic Church had become a bulwark of Ukrainian national sentiment; now, in post-World War II North America, both the Ukrainian (Greek) Catholic and Ukrainian Autocephalous Orthodox churches became institutions through which Ukrainian Americans and Ukrainian Canadians could feel that they were defending ancestral religious traditions which were imperilled in the Soviet-ruled homeland. In essence, one's Catholic or Orthodox faith or one's nominal association with the church became — and remains — a central component of Ukrainian ethnic identity in North America.

Economic life and interaction with Jews

Since Jews and Ukrainians in the diaspora tended to live in the same geographical locations, in particular with regard to the northeast United States, it is not surprising that both peoples interacted in the economic sphere. This was especially the case during the first two periods of immigrant life (from the 1880s to the outbreak of World War II), when in downtown areas of many northeastern American towns and cities it was not uncommon to find Jewish-owned small retail shops and later department stores patronized by Ukrainian customers, if for no other reason than because this had been normal practice in the old country.

The highly articulate and nationally conscious third wave of DP (Displaced Persons) Ukrainian immigrants who arrived after World War II brought with them the organizational skills they had learned in Austrian-and Polish-ruled Galicia. This meant that, instead of having to depend on financial institutions owned by Jews or by any other American or Canadian body, Galician-Ukrainian immigrants, in particular, set up an extensive network of credit associations and mutual-benefit societies (some of which had already existed in North America) to help provide loans to start up or expand urban-based businesses, to purchase farm equipment, or to assure a mortgage on a family home. Many of these cooperative-like organizations still exist in North American towns and cities, where they are easily visible by their Cyrillic-alphabet signs (alongside English) and in some cases a blue and yellow Ukrainian flag fluttering above the storefront.

Click here for a pdf of the entire book.