Chapter 10.2: "Jews and Ukrainians: A Millennium of Co-Existence"

Jews and Ukrainians: A Millennium of Co-Existence is an award-winning book that explores the relationship between two of Ukraine’s most historically significant peoples over the centuries.

In its second edition, the book tells the story of Ukrainians and Jews in twelve thematic chapters. Among the themes discussed are geography, history, economic life, traditional culture, religion, language and publications, literature and theater, architecture and art, music, the diaspora, and contemporary Ukraine before Russia’s criminal invasion of the country in 2022.

The book addresses many of the distorted stereotypes, misperceptions, and biases that Ukrainians and Jews have had of each other and sheds new light on highly controversial moments of Ukrainian-Jewish relations. It argues that the historical experience in Ukraine not only divided ethnic Ukrainians and Jews but also brought them together.

The narrative is enhanced by 335 full-color illustrations, 29 maps, and several text inserts that explain specific phenomena or address controversial issues.

The volume is co-authored by Paul Robert Magocsi, Chair of Ukrainian Studies at the University of Toronto, and Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern, Crown Family Professor of Jewish Studies and Professor of History at Northwestern University. The Ukrainian Jewish Encounter sponsored the publication with the support of the Government of Canada.

In keeping with a long literary tradition, UJE will serialize Jews and Ukrainians: A Millennium of Co-Existence over the next several months. Each week, we will present a segment from the book, hoping that readers will learn more about the fascinating land of Ukraine and how ethnic Ukrainians co-existed with their Jewish neighbors. We believe this knowledge will help counter false narratives about Ukraine, fueled by Russian propaganda, that are still too prevalent globally today.

Chapter 10.2

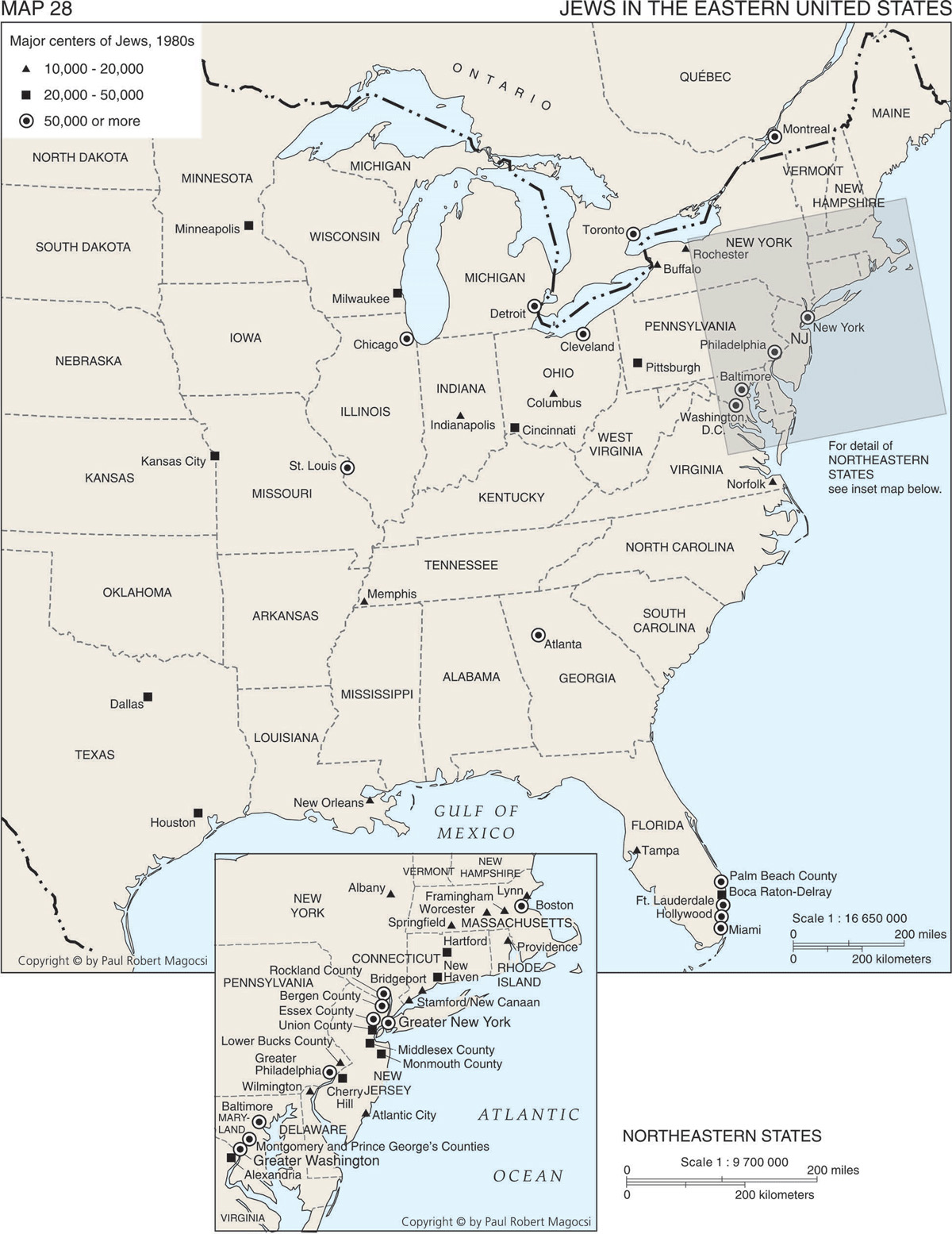

Main centers of Jewish emigration

The earliest seventeenth-and eighteenth-century Jewish emigration to pre-revolutionary America was Sephardic from Holland and the Dutch colonies, but by the nineteenth century it had become predominately Ashkenazic. Until the 1880s most Ashkenazi Jewish immigrants came from Germanic lands, but thereafter the majority originated in central and eastern European Slavic territories. Between 1882 and 1924, no less than 2.3 million Jews entered the United States. More than 75 percent of them were from the Russian Empire and about 20 percent from Austrian Galicia. In contrast to other European immigrants headed for North America, 44 percent of the Jewish newcomers were female, which implies that Jewish migrants came to settle, not to make quick money and return home. In fact, about 3 to 4 percent returned to Europe, mainly to England; some were either sent back because of illness (trachoma or tuberculosis) or unacceptable political activity, while others went back on their own accord for personal reasons.

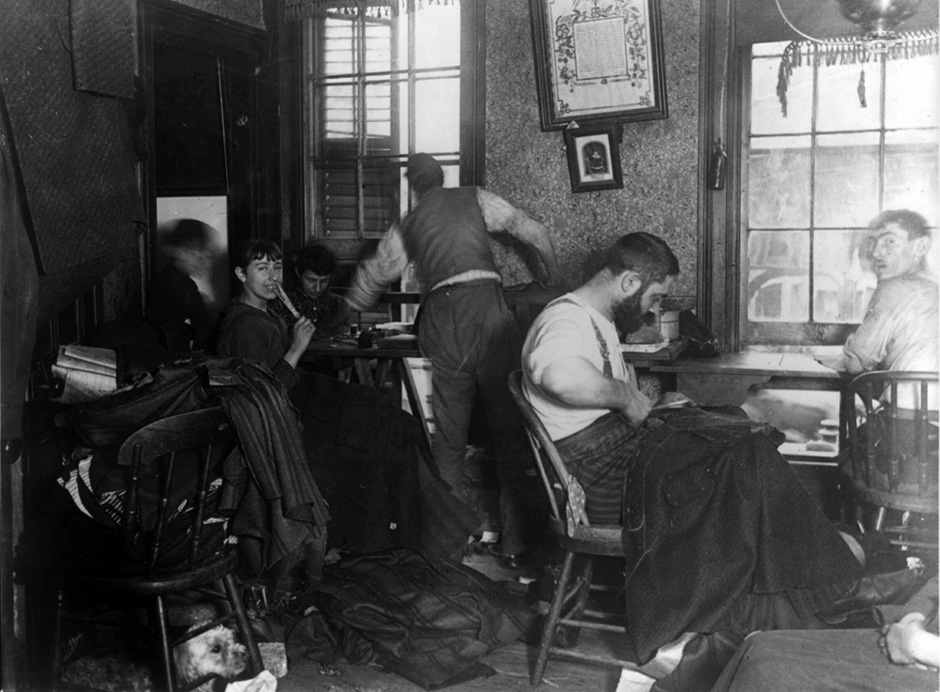

The second half of the twentieth century witnessed massive Jewish emigration from Europe, first among Holocaust survivors just after World War II, then, beginning in the 1970s, increasing numbers from the Soviet Union because of political and social discontent. Among the major destinations were Israel (over a million), the United States (500,000), and Germany (200,000), with smaller numbers to Canada (30,000) and elsewhere. The most recent wave is connected with the Revolutions of 1989 that toppled Communist regimes in central Europe and the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, prompting the departure of about 1.5 million Jews. Among these emigrants, about 60 percent went to Israel and 30 percent to the United States and Canada. Since Jews from Ukraine made up roughly one-third of the central and eastern European Jewish emigration, an estimated 330,000 Israeli Jews, 150,000 American Jews, and more than 60,000 German Jews came from Ukraine between 1989 and 2010. Jewish immigrants to the United States and Canada were from the outset religiously and culturally diverse, speaking a wide variety of languages ranging from Ladino and Yiddish to Russian and Hungarian. Most were skilled workers with transferable professions, and throughout the twentieth century in both North American countries they had similar labor patterns: working at first in the sweatshops of the garment, tobacco, and construction industry; later becoming small-scale merchants and shop owners (particularly bakers and butchers); then owning manufacturing enterprises. Many such working-class Jews were attracted to leftist political ideologies and workers' and union movements. Their struggle against exploitation and attachment to socialist views was reflected in the widely read New York City-based Yiddish daily newspaper, Forverts, which by the 1930s had a circulation of 175,000. With the lifting after World War II of the racial and antisemitic restrictions and anti-Jewish quotas at higher educational establishments in the United States and Canada, Jews became doctors, lawyers, pharmacists, dentists, engineers, administrators, and college educators. It was not long before they were disproportionately overrepresented in professions such as these from which they had previously been banned.

Settlement patterns

The destination for Jewish emigrants from Ukraine varied, depending on immigration policies of the receiving countries. For example, in the 1990s Israel put pressure on the United States in an effort to redirect the flow of emigrants. It wanted that their destination be Israel, not the United States, which in any case sought ways to curtail its intake of Jews from eastern Europe. Therefore, whereas in the 1980s, 72 percent of all Jews emigrating from the Soviet Union preferred the United States and only 26 percent Israel, after the collapse of the Soviet state in 1991 the situation radically changed. From then on, those who chose Israel as their destination significantly grew, eventually reaching 70 percent of all emigrants. As for the rest, the percentage of those headed for the United States diminished, while the percentage that chose Germany remained stable.

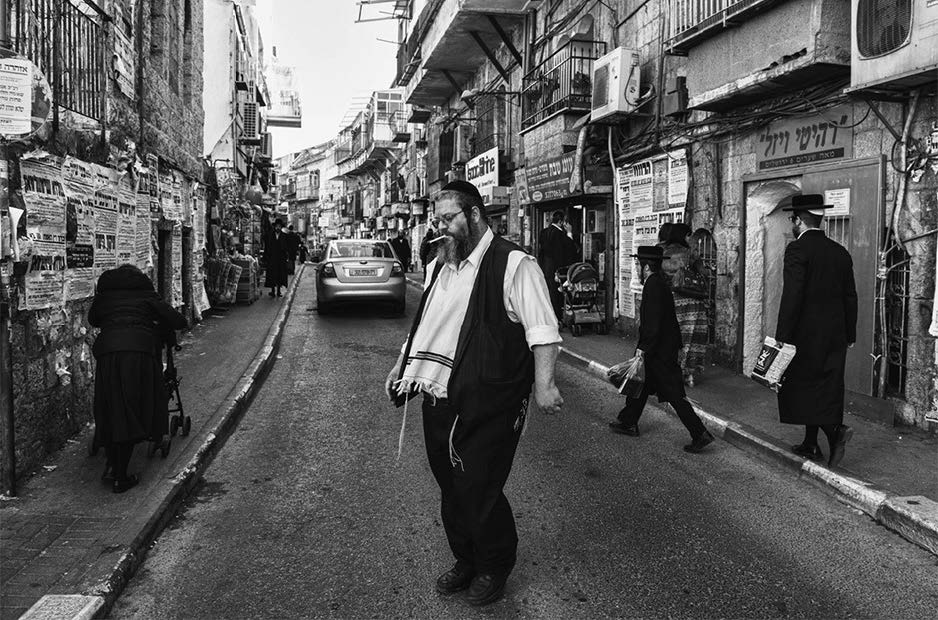

Traditionally Jews went to Israel for ideological reasons, but the post-1989 emigrants were driven predominantly by economic concerns and the search for countries with better and more stable socio-economic conditions. Therefore, if they had an option, Jews with higher education and in a younger age bracket preferred the United States, whereas older migrants chose Israel and even Germany, particularly if they could not expect to find a relatively similar job or if they planned to rely on social welfare. Take Israel, for example. Between 2000 and 2012, one-third of the 27,000 new Jewish immigrants (olim) from Ukraine were thirty years or older, and 70 percent of them were of mixed origin (one parent being non-Jewish). Only one-third came from major cities (Kyiv, Odessa, Kharkiv, and Dnipropetrovsk), whereas two-thirds came from small towns and were therefore much less urbanized than their predecessors who had left for Israel in the 1990s. At the same time, the ratio of Israel's new Jewish immigrants from Ukraine with higher education has dropped from 75 to 30 percent. This lessened the chances for newcomers to obtain high-paying jobs in the Israeli economic or state sector. It is for such economic reasons that Jews from Ukraine preferred less expensive places to live (Ashdod, Ashkelon, Bat Yam, Haifa, Netanya, Rehovot, Rishon LeZion), which they have transformed into an Israeli diaspora version of multilingual and secular Odessa, very much as they had done earlier in the Brighton Beach section of Brooklyn, New York.

Starting with the first great wave of Jewish emigration in the 1880s, Jews preferred to settle in ghetto-like urban enclaves of large cities in the United States and Canada. By the 1920s, for example, one-quarter of all American Jews lived in New York City, with an average 10 percent each in six other cities (Cleveland, Newark, Philadelphia, Boston, Pittsburgh, and Chicago). At the same time in Canada, most Jews settled in urban Montreal, Toronto, and Winnipeg, although some settled already before World War I in organized farm colonies in the Canadian Praires, or later in rural areas of Quebec and Ontario where they turned to farming.

These early settlement patterns were in large measure dictated by the desire to stay close to urban-based Jewish communal and religious centers. At the end of the twentieth century, however, Soviet Jewish immigrants, who were much more secularized than their brethren a hundred years before, were driven by economic rather than religious interests. Hence, the recent wave of Jewish immigrants to the United States is geographically distributed more evenly: about 40 percent in the northeast United States (New York, New Jersey, Massachusetts, Pennsylvania), 10 percent in the mid-west (Ohio, Illinois), 26 percent in the south (Florida, Texas), and 24 percent in the far west (California). With the exception of Brooklyn, New York, where at least 100,000 Jews from Ukraine have settled, most Jewish newcomers prefer the suburbs of large cities.

Civic, cultural life, and economic life

In North America, Jews organized so-called landsmanshaftn. These were voluntary self-governing societies whose members came from the same town or same region in Europe. In the decades before World War I, dozens of such societies emerged, bringing together former residents from places in Russian-ruled Ukraine and Austrian-ruled Galicia. The landsmanshaftn were registered as non-profit organizations responsible for philanthropic activity and social relief, which included sponsorship of nursing homes and the establishment of elementary religious schools (hadarim), hospitals, orphanages, and cemeteries. Eventually, these bodies turned into influential institutions in their own right, serving Jews not only from central and eastern Europe but from the North-American Jewish community as a whole.

Jews from the former Russian Empire and Soviet Union transformed the cultural space in which they settled as immigrants. This first happened in New York City on the Lower East Side, the Bronx, and, by the last decades of the twentieth century, in Brooklyn, where Yiddish and then Russian came to dominate the public sphere. Most recently this pattern has been repeated along Israel's Mediterranean coast. Russian seems to be everywhere: in the streets, on the boardwalks, in cafeterias, in supermarkets, bookshops, and in hair salons. Israel's new immigrants (olim) from Ukraine read Russian newspapers, watch Russian and Ukrainian TV channels, and purchase food in stores that have only Russian-language labels.

Jewish immigrants from the former Soviet Union represent about 45 percent of Israel's secular population. At the height of community activity in the late 1990s, they had at their disposal more than a hundred Russian-language newspapers, including the daily Vesti (with a circulation of over 50,000), and several Russian-language radio and television stations, including Israel Plus with an audience of one million. The result has been the formation in Israel of a Russian-Jewish fusion culture that is different both from Israeli culture and from that which the immigrants brought from Ukraine. This new reality was perhaps best summed up during the winter of 2014, when Israel experienced an exceptionally heavy snowfall. The government was forced to bring in military vehicles in order to clear the streets, to which an Israeli of non-Soviet background waiting at Jerusalem's Central Bus Station exclaimed: "Tanks. Snow. Russians. Where am I?"

While first-generation Jewish immigrant parents have held on to the secular values of Soviet high culture and identified their Jewishness only through memories of antisemitism and victimization in the old country, their North American-born or acculturated children have swiftly assimilated into globalized American pop culture. Young Jews are simply reluctant to identify with the sufferings of their parents. Sociologists use a special "index of dissimilarity" to mark the level of difference of an immigrant group within a given society. Among former Soviet Jews the dissimilarity is lower than that of other immigrant groups, despite the constant influx of new immigrants. For example, in the United States the index of dissimilarity among Jews dropped at the end of the twentieth century from level 40 to 30.

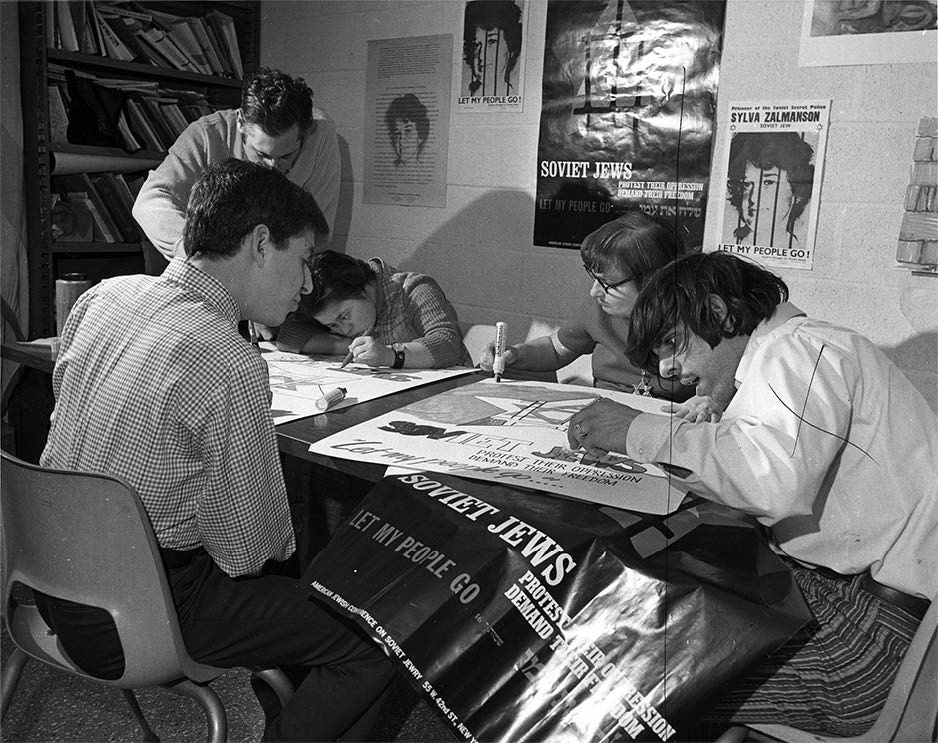

Considering the modest level of integration of Soviet Jews into diasporan Jewish community life, it becomes clear that immigrants have replaced the enforced assimilation that had shaped their lives in the Soviet Union with assimilation by choice. In 1990 many U.S.-based Jewish organizations celebrated victory in their twenty-five-year-long struggle to allow Jewish emigration from the Soviet Union, characterized at the time by the abridged biblical verse "Let my people go!" And yet, by the outset of the twenty-first century, these same organizations realized that they had almost completely lost the struggle to incorporate former Soviet Jews into North American diasporan community life.

For example, the new immigrants, who were accustomed to free education in the Soviet Union, were not prepared to send their children to (quite expensive) Jewish day schools in North America. They were also unable or unwilling to pay (quite high) synagogue membership fees. Hence, they remained a community, or rather an assortment of individuals, whose values and traditions had very little in common with North American Jews who were committed to their Judaic national, ethnic, and religious traditions, whatever the financial costs. While some former Soviet Jews have joined one or another religious congregation (Reform, Conservative, Reconstructionist, Orthodox, and Hasidic — especially Habad), the overwhelming majority of Jews from Ukraine (and Russia) have remained outside North American community and synagogue life. It turns out that the second half of the biblical verse "Let my people go," which reads: "so that they would serve Me, says God the Lord," has effectively not come about. In short, a religious, in contrast to an ethnocultural, Jewish identity was reclaimed only by a very few of former Soviet Jews in the present-day North America diaspora and Israel.

This lack of Judaism among new immigrants is especially evident in New York City, with its 250,000 former Soviet Jews. They have formed a new identity, a kind of Jewish-American version of homo sovieticus. In Brooklyn, where they live in highest concentration, the recent immigrants go to stores, cafeterias, and restaurants with Slavic names, eat delicatessen food (precisely that which was practically unavailable in the Soviet Union), read Russian-language newspapers and books, listen to Russian CDs, watch Russian-language television, flock to concerts of former Soviet sphere pop-singers, and, aside from speaking Russian mixed with English, dress in clothing styles that were considered fashionable in the Soviet Union in the 1970s and 1980s. The cultural distinctiveness of these Jewish immigrants from the Soviet Union is at once charming and alarming to those who arrived before. Able to live their lives without any contact with multicultural American life and not speaking English, they like to joke: "Why do I need English? I don't go out in America (v Ameriku ne khozhu)." This self-contained culture is the focus of many tragicomic texts by Vladimir Matlin, Serguei Dovlatov, and Dina Rubina.

The situation among former Soviet immigrants in Israel is significantly different. Israel's efficient secondary and high school education system, the country's relatively efficient bureaucracy, and in particular the Israeli army with its compulsory system of service has helped to absorb swiftly and successfully the younger generation. Required from an early age to learn Hebrew, young people easily join various civic and social groups in Israeli society, take up residence in various parts of the country, and become active in the military, the business world, university life, and the hi-tech industry.

Religious life

Following the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 Jewish immigrants in their new countries discovered things that were unavailable or restricted to them when they lived in Soviet Ukraine. Among such things were various forms of organized and institutionalized religion — in a word, Judaism. Some younger-generation Jews in diaspora countries explored their Jewish roots, becoming involved in Jewish Sunday schools, synagogues, youth movements, Orthodox yeshiva and study groups, and communal life in general. The Orthodox Hasidic Habad-Lubavitch movement was particularly successful in engaging many younger Jews. Hasidic Orthodoxy, with its internal rigidity and personal obligations that many considered burdensome, did not have broad appeal, however.

Many more Soviet Jewish youth, especially in North America, were unaware of the age-old struggle of the Orthodox against the Reform in their European countries of origin. Oblivious to the past, they chose to become associated with a variety of liberal movements ranging from Conservative to Reform to Egalitarian. But even these less rigid forms of Judaism turned out to be burdensome. Unable to pay communal/synagogal dues and unfamiliar with the concept of tuition for a secondary education, most recent immigrant Jewish families have opted not to send their children to religious Jewish schools, whether in Israel or North America.

Interaction with ethnic Ukrainians

Why have most Jews from Ukraine become part of Russian-speaking Jewish communities in the new countries to which they immigrated? Why have so few chosen to identify with the Ukrainian language and culture? Of those who arrived in Israel or North America in the last decades of the twentieth century, most came from highly urbanized and culturally russified territories of Ukraine. It was, therefore, logical for these immigrants to continue using the language they had used in Soviet or independent Ukraine. Moreover, Russian was also the language widely used by immigrant organizations and cultural institutions that had come into being in the 1970s and 1980s. Because of an often simplistic bureaucratic mindset, officials in the receiving countries identified all Jewish newcomers from the Soviet Union — whether from Ukraine or any other Soviet republic — as "Russian Jews." This should not come as a surprise, since, for most Americans, Canadians, and Israelis, the entire former Soviet Union was "Russia."

On the other hand, the established ethnic Ukrainian communities already existing in the United States, Canada, or Germany were, in general, not particularly welcoming nor willing to consider Jewish immigrants from Soviet Ukraine as "their own." As typical of many diasporas, the Ukrainian community was not only introverted but filled with all sorts of misconceptions regarding Jews and for a long time even a degree of latent antisemitism. Despite years of persecution of Jews in the Soviet Union, many in the Ukrainian diaspora still entertained the conviction that Jews had always been staunch supporters of communism and therefore an integral part of the Soviet system which, in turn, persecuted ethnic Ukrainians. One must also take into consideration that diaspora Ukrainian communities were relatively more religiously cohesive than the predominantly secular Jews who emigrated from Soviet Ukraine in the decades after World War II. Neither Jews from Ukraine nor ethnic Ukrainians were ready to embrace one another, to recognize their common pasts, or to view the other as a people whose culture had been suppressed and persecuted throughout the Soviet empire. This situation has only begun to change — albeit very slowly — since the 1990s.

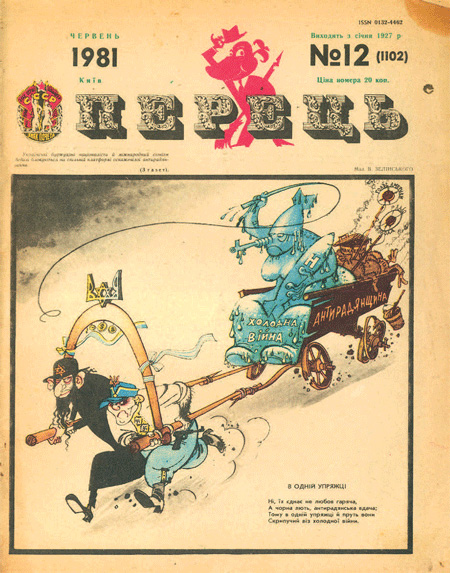

The barrier between ethnic Ukrainians and Jews from Ukraine in the diaspora is the result not only of internal factors but also of important external ones. Policy-makers in present-day Russia have manipulated the pro-Russian linguistic and cultural attachment of Jewish immigrants from the former Soviet Union. The goal of these policy-makers is to advance the concept of a cohesive Russian-centered imperial entity and, in the process, to denigrate the former Soviet but now independent republics, first and foremost Ukraine, which is often considered little more than a bogus state. Soviet and now Russian policy-makers have long sought to keep apart ethnic Ukrainians and Jews in the diaspora and in Ukraine, to denigrate Ukraine and ethnic Ukrainians in Jewish eyes, and to make the spurious claim that every time Ukraine strove to be independent it became viciously antisemitic.

Documents from recently declassified KGB archives in Ukraine reveal that Soviet state security services had at least since the Cold War initiated campaigns aimed at provoking animosity between diasporan Jews and Ukrainians, particularly in the United States. Present-day language policies seem to be a logical continuation of trends from the previous half-century. Consequently, the Russian-language media in the diaspora quite often reprints Russian publications which simply toe Moscow's standard anti-Ukraine line when reporting on events in independent Ukraine. This kind of aggressive, anti-Ukrainian propaganda is still very much part of the Russian Federation's international media campaigns, particularly when it comes to sensitive issues related to the Jewish-Ukrainian historical past.

Click here for a pdf of the entire book.