Chapter 10.3: "Jews and Ukrainians: A Millennium of Co-Existence"

Jews and Ukrainians: A Millennium of Co-Existence is an award-winning book that explores the relationship between two of Ukraine’s most historically significant peoples over the centuries.

In its second edition, the book tells the story of Ukrainians and Jews in twelve thematic chapters. Among the themes discussed are geography, history, economic life, traditional culture, religion, language and publications, literature and theater, architecture and art, music, the diaspora, and contemporary Ukraine before Russia’s criminal invasion of the country in 2022.

The book addresses many of the distorted stereotypes, misperceptions, and biases that Ukrainians and Jews have had of each other and sheds new light on highly controversial moments of Ukrainian-Jewish relations. It argues that the historical experience in Ukraine not only divided ethnic Ukrainians and Jews but also brought them together.

The narrative is enhanced by 335 full-color illustrations, 29 maps, and several text inserts that explain specific phenomena or address controversial issues.

The volume is co-authored by Paul Robert Magocsi, Chair of Ukrainian Studies at the University of Toronto, and Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern, Crown Family Professor of Jewish Studies and Professor of History at Northwestern University. The Ukrainian Jewish Encounter sponsored the publication with the support of the Government of Canada.

In keeping with a long literary tradition, UJE will serialize Jews and Ukrainians: A Millennium of Co-Existence over the next several months. Each week, we will present a segment from the book, hoping that readers will learn more about the fascinating land of Ukraine and how ethnic Ukrainians co-existed with their Jewish neighbors. We believe this knowledge will help counter false narratives about Ukraine, fueled by Russian propaganda, that are still too prevalent globally today.

Chapter 10.3

Ukrainian diasporan impact

Canada and the United States

The status of Ukrainians in the United States and Canada has differed substantially with regard to their respective impact on the host society. The basic reason for the difference is the group's relative size. Today the number of persons officially recorded as Ukrainian in each country is about one million; this means that in Canada one out of every 35 inhabitants is of Ukrainian background, whereas in the United States the figure is one out of every 350. Aside from their numerical disadvantage, Ukrainians in the United States have never formed a critical mass in any one area and therefore have been unable to form an effective bloc whose vote might be courted by American political parties, even at the municipal level. In Canada, on the other hand, Ukrainians have at least since the 1920s become a force to be reckoned with not only in the rural bloc communities but also at the provincial level. It was and still is common to find politicians of Ukrainian background — and who openly identify as such for political reasons — in positions as premiers, lieutenant governors, government officials, and provincial legislature deputies (MPPs) in Alberta, Manitoba, and Saskatchewan, as well as federal parliamentary members (MPs) and life-long appointed senators in Ottawa. In the 1990s the highest office in the land, the queen's representative as governor general, was held by the Ukrainian-Canadian politician Ray Hnatyshyn. In effect, for nearly the past century Ukrainians have been a factor in Canadian political life.

The contrast between Canada and the United States could not be greater. Aside from the miniscule numerical size of Ukrainians in relation to the total population of the United States and their limited presence in the political arena, American society, whether in the media or in other aspects of public discourse, has traditionally not even recognized the existence of Ukrainians. The following scenario was until very recently quite common. A fellow American might ask, "What is your background?" and receive the response "Ukrainian"; the retort of the questionnaire would likely be: "Oh, so you're Russian"! The situation has changed somewhat since 1991: independent Ukraine has its own Olympic teams, the 2004 Orange Revolution was covered widely by the American media, and mainline television programs sometimes refer to Ukrainians and even a "Ukrainian mafia." Nevertheless, the misleading assumption that Ukrainian and Russian are the same thing has not yet disappeared in the United States.

Considering such demographic and perceptual realities, it is not surprising that the Ukrainian-American community has had limited or no real influence either on the political life of the United States or on that country's foreign policy toward the Ukrainian ancestral homeland. Not that Ukrainian-American activists have not tried to exert some kind of influence. They did lobby in Washington at the close of World War I in an effort to elicit support for an independent Ukraine, or for a favorable solution to the Ukrainian-Polish war over Galicia. But their anti-Polish and anti-Soviet views were not met with sympathy among American politicians, especially during World War II, when the United States was an ally of the Soviet Union.

The only time Ukrainian-American political activists seemed to gain a hearing and achieve some of their goals was during the early stage of the Cold War. The lobbying efforts undertaken in Washington, D.C., by the then recently founded umbrella group, the Ukrainian Congress Committee of America (est. 1944), seemed to bear fruit in the early 1950s, when the U.S. government allowed anti-Soviet Displaced Persons (about 50,000 of whom were Ukrainians) into the United States. It was not long, however, before the Ukrainian Congress Committee and the subsequently founded World Congress of Free Ukrainians (est. 1967) became somewhat of an embarrassment for American foreign policy-makers. Government officials and their advisers (including America's new generation of Russia specialists) looked with increasing suspicion at what was considered the extreme anti-Soviet views and unnecessarily provocative public protests by Ukrainian-American activists outside Soviet diplomatic missions in Washington, D.C., and New York City, especially in the 1970s and 1980s when détente with the Soviet Union was the American foreign-policy order of the day. As late as the waning months of the Soviet Union, Ukrainian-Americans were faced with the reality of their president (George H.W. Bush) visiting Soviet Ukraine for a few hours in August 1991 and delivering his so-called Chicken-Kyiv speech, in which he called on Ukrainians to avoid extremist measures and instead to remain within the already tottering Soviet state. It is only since Ukraine's independence that Ukrainian Americans have had some real impact on their government, whether through the work of the U.S. Congress Ukraine Caucus or through the advice solicited from Ukrainian-American civic activists and scholars who have appeared before various congressional committees and governmental bodies in Washington, D.C.

By contrast, Ukrainian Canadians have had greater success in having their voice heard and their needs responded to by various levels of Canadian society. Activists in the Ukrainian Canadian Congress — an umbrella group of organizations established at the initiative of the Canadian federal government in 1945 — were successful in convincing officials in Ottawa to allow entry and permanent residence for Ukrainian war refugees. Included among them were certain groups and individuals who may have served on the side of Nazi Germany. Even more influential was the role played by Ukrainian Canadians in formulating the policy of multiculturalism. Implemented in the 1970s, that policy encouraged the federal and provincial governments to provide state funding for Ukrainian-language educational programs and cultural activity designed to preserve and enhance Ukrainian identity in Canada. Considering all these developments, it is perhaps not surprising that when Ukraine declared its independence in August 1991, Canada was the first country (after Poland) to recognize formally the new state.

Jewish diasporan impact

North America and Israel

Not long after eastern European Jews in North America established landsmanshaftn made up of former residents of a specific town or region in Europe, umbrella organizations emerged that were primarily concerned with relations between Jews and non-Jews. Among the oldest of these was the American Jewish Committee, established in 1906 to lobby on behalf of the domestic concerns of Jews in the United States, including issues such as anti-Jewish legislation, immigration restrictions, educational quotas, and antisemitism. In the wake of World War I, the newly founded American Jewish Distribution Committee provided social relief to help overseas Jewish communities re-establish themselves. Then, during World War II, the Jewish Welfare Board was created to help Holocaust refugees.

In the 1960s, several organizations ranging from the radical Jewish Defense League to the moderate American Committee for Soviet Jewry came into being with the goal of improving the status of Soviet Jews and assisting them in their struggle for the right to emigrate abroad. In Canada, too, similar organizations appeared, including the influential Canadian Jewish Congress, established in 1919. It initially focused on combatting antisemitism but later became a major lobbying organization. The Congress was later reinforced by perhaps one of the most effective pro-Israeli groups in the world, the Canadian Zionist Federation Hadassah — WIZO (est. 1967). It was responsible for extensive fund-raising campaigns, combatting anti-Israeli boycotts, and promoting a wide range of welfare projects.

Among the main concerns of Jewish umbrella organizations were education opportunities. Until well into the twentieth century, Jews were banned from holding professorial posts in many American colleges and universities. This situation began to change in the late 1930s, when a leading literary critic of Jewish descent, Lionel Trilling, was appointed professor in the English Department at Columbia University in New York City. During the same decade, the establishment of the Chair in Jewish Studies, also at Columbia University, first held by the distinguished historian Salo Baron (a native of Galicia), opened up further possibilities for the academic development of Jewish studies in America. Baron's seventeen-volume Jewish social history and three-volume history of the Jewish community became landmarks in Jewish historical studies.

By the late 1960s, Jewish studies professors became the norm at American and Canadian universities, and their subject matter an integral part of many institutions of higher learning. Other institutions associated specifically with major religious trends in Judaism appeared in various places: the Reform Judaism university, Hebrew Union College (1875); the Conservative Jewish Theological Seminary of America (1886); Yeshiva University (1886), associated with modern Orthodoxy; and the youngest among them, the Reconstructionist Rabbinical College (1968). Aside from programs leading to rabbinic ordination, some award degrees in the liberal arts and in the social, applied, and natural sciences.

With regard to political preferences, the arrival of Soviet Jews in the last decades of the twentieth century has profoundly altered voting patterns in the eastern European Jewish diaspora. In Canada, 40 percent of middle-aged Jews vote for the Conservatives and 30 percent for the Liberals, while among younger Jews the percentages are reversed: 20 percent for the Conservatives and 40 percent for the Liberals. In the United States, most Jews had traditionally voted Democratic, particularly because of the favorable stance of that party toward Medicare and other social-welfare issues. But, by the outset of the twenty-first century, many more Soviet Jewish immigrants drifted to the Republican side, predominantly because of the sympathetic Republican position on Israel and because of Jewish dissatisfaction with the increasingly suspicious socialist and anti-Israel rhetoric of the American democratic left.

In Israel, Jewish and non-Jewish immigrants from the former Soviet Union constitute about 17 percent of the country's Jewish population. As such, they have become a crucial electoral constituency taken seriously in the often fractious world of Israeli politics. Initially, Jews from Ukraine and the former Soviet Union as a whole entered Israeli politics by forming parties with local community agendas. By the beginning of the twentieth century, however, they had adopted a broader political vision concerned with issues that face Israeli citizens at large. Although some Soviet Jews have supported the Israeli democratic and socialist left, more tend to support the center-right parties such as Likud and Israel Beiteinu (Our Home Israel). It is therefore not surprising that leading politicians like Benjamin Netanyahu and Avigdor Lieberman have relied heavily on the political support of the recent immigrants (olim) from Ukraine, Moldova, Belarus, Russia, and the central Asian republics of the former Soviet Union.

Since the foundation of Israel in 1948, many Jews from Ukraine have become highly visible on the Israeli political stage. Three of them — Moshe Sharett, Levi Eshkol, and Golda Meir — became prime ministers and two — Yitshak Ben-Zvi and Ephraim Katzir (Katchalski) — held the office of president. In more recent times several others have held important positions in the Israeli government. Among the more charismatic of these is Natan (Anatolii) Sharansky from the Donetsk region, a dissident who served a full eight-year term in the Soviet gulag for human-rights activities. After moving to Israel, he founded in 1990s the Israel ba-Aliyah (Israel on the Rise) party, served as its parliamentary deputy, was appointed a cabinet minister, and headed the Jewish Agency for Israel (Sokhnut) organization. Others from Ukraine include Yuli Edelstein, a leading Zionist and Soviet refusenik from Chernivtsi who served as a parliamentary deputy and cabinet minister in several Israeli governments; Faina Kirshenbaum from Lviv, a leading Israel Beiteinu party activist and parliamentary deputy; and Zeev Elkin from Kharkiv, a historian who switched to politics, serving in more than one Israeli party before becoming chairman of a broad political coalition in the Israeli parliament (the Knesset).

Interaction with ethnic Ukrainians

In the immediate post-World War II decade, individual Jews in North America and Europe undertook multiple attempts to bridge the gap between ethnic Ukrainians and Jews in the diaspora and to oppose efforts to pit one people against the other. In 1953, a Jewish-American lawyer, Raphael Lemkin (a Polish Jew who studied in Lviv), gave a speech at New York City's Manhattan Center to commemorate the twentieth anniversary of Ukraine's Holodomor. A decade earlier, in 1943, Lemkin had coined the word genocide to convey the destruction of a people simply because of its specific ethnic origins. Now he classified Ukraine's Holodomor as an act of genocide.

By the 1960s, Ukrainian and Jewish intellectuals, mostly in Canada, Israel, and the United States, began to realize the extent to which the two peoples had become a crucial factor in the struggle for a future independent Ukraine. There were Ukrainian emigrés who still followed Dmytro Dontsov, the interwar integral nationalist thinker who, when living in Canada after World War II, continued to promote the idea of Ukraine as a country belonging exclusively to ethnic Ukrainians. By contrast, a newer generation of Ukrainian intellectuals adopted the ideas of another interwar diaspora political theorist, the liberal nationalist Vyacheslav Lypynskyi, who envisioned a future independent Ukraine as a multi-ethnic state.

Following Lypynskyi's vision, some Ukrainian activists in the American zone of Germany, starting in the 1960s, attempted to build bridges between ethnic Ukrainians and Jews. Particularly active in this regard were individuals associated with the Munich-based Ukrainian Free University, the Ukrainian Division of Radio Liberty/Free Europe, and the monthly journal Suchasnist. For example, Suchasnist — perhaps the most intellectually influential Ukrainian diaspora publication during the second half of the twentieth century — regularly published articles by Jews about the experience of former prisoners of conscience (Yosif Mendelevich, Israel Kleiner, Avraam Shifrin, Yakiv Suslenskyi); about Jewish literature (Joseph Roth, Isaac Babel), art, theater (Solomon Mikhoels), and scholarship (Moisei Beregovskii); and about Jewish-Ukrainian relations in general, including the most important past and present figures engaged in the dialogue between the two peoples (Solomon Goldelman, Arnold Margolin, Zynovii Antonyuk, and Yevhen Sverstyuk).

In Israel, this new trend was evident in the activities of a group of civic activists who in 1981 established the Society of Jewish-Ukrainian Relations and contributed to the journal Diyalohy (Dialogues), edited by the Ukrainophile Jew, Yakiv Suslenskyi. The group included former Soviet dissidents, underground Zionists, and prisoners who while incarcerated in the gulag "discovered" Ukraine and the Ukrainian language and culture through their friendship with fellow Ukrainian nationalist inmates. These activists sought to convince other members of the Soviet intelligentsia now living in Israel that there existed significant philosemitic trends in Ukrainian literature, politics, and culture, that the antisemitic excesses in Ukraine were not always and not necessarily perpetrated or orchestrated by ethnic Ukrainians, and that Ukrainians and Jews, who both were victims of imperial policies, shared a common cultural and historical experience.

From the mid-1980s to mid-1990s, this informal and unaffiliated group struggled with the Israeli authorities to gain recognition of the unique role of those Ukrainian nationalists who during World War II opposed both the Bolsheviks and the Nazis and who did not commit crimes against Jews in western Ukraine. Suslenskyi and his supporters also launched an international campaign to persuade Israel's Yad Vashem Holocaust remembrance authority to acknowledge the Greek Catholic Metropolitan Andrei Sheptytskyi as a Righteous Gentile. Although they did not succeed, their efforts nonetheless attracted international attention and encouraged scholars and thinkers in the diaspora and in post-Soviet Ukraine to re-evaluate the role of Ukrainian national leaders during World War II, whom Soviet historians continued to depict as assassins, Nazi-puppets, and Jew-haters. The journal Diyalohy even took the courageous step to publish an entire gamut of contradicting views on Ivan Demyanyuk's trial in Israel (see Chapter 12).

The large wave of ethnic Ukrainians who settled in Israel from the early 1990s have in recent years established a variety of diaspora organizations. These include the Union of Ukrainians in Israel, the Ukrainian Info Center, and most recently the Israeli Friends of Ukraine. Through various kinds of activity (concerts, lectures, festivals, Internet sites) these organizations strive to promote awareness of Ukraine and Ukrainian culture among the larger Israeli society.

Ashkenazic Israelis treat these relatively new Israeli Ukrainians with sympathy, recognizing in them the commonality of their European origin. On the other hand, Sefardi Israelis often refer to the ethnic Ukrainian newcomers as aliens, whom they consider (as they do Ashkenazic Jews) not a genuine component of the Land of Israel. Nevertheless, both the Ukrainian Embassy and the Israeli government support the country's ethnic Ukrainians through co-sponsorship of institutions such as the Association of Ukrainian Immigrants in Israel.

Ukrainian literary culture in Israel is expressed through the work of translators, who contribute to Ukrainian-Jewish reconciliation by publishing the works of leading Ukrainian and Jewish writers in Hebrew or in Ukrainian translations. There are also two Ukrainian-language journals — Sobornist (Unity) and Vidlunnya (Echo) — whose contributors form a small island of Ukrainian language and culture in Israel. For the most part, however, they are isolated from Israel's larger formerly Soviet Jewish community and continually must struggle to prove the validity of their Ukrainian-oriented cultural strivings in the face of the Israeli establishment, whose support is usually allocated to Russian literary and cultural institutions. Somewhat more engaged with Israeli society, although in the limited realm of academic life, are the various projects at universities that deal with Ukraine and Jews from that country. Israeli academics at Hebrew University in Jerusalem and at Tel Aviv University, among others, have in the last two decades published scholarly works that deal in particular with medieval and early modern (Slavonic) aspects of history and culture in Ukrainian lands, and in 1993 the Israeli Association of Ukrainian Studies was established for scholars interested in Ukrainian matters.

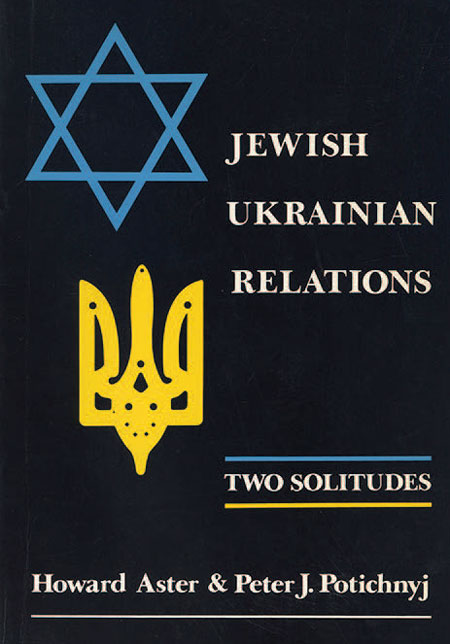

The tendency toward a sense of Jewish-Ukrainian awareness and cultural rapprochement has a longer tradition in North America. In the late 1960s, a spirited debate between Ukrainian and Jewish historians (Taras Hunczak and Zosa Szajkowski) about the fate of Jews in Ukraine at the close of World War I — the Petlyura problem — was launched on the pages of the American journal Jewish Social Studies. Then, in 1983, a landmark scholarly conference dealing with the whole gamut of historic relations between Jews and Ukrainians took place at McMaster University in Canada. Organized by the Ukrainian-Canadian and Jewish-Canadian historians Peter Potichnyj and Howard Aster, and with the participation of scholars and literary figures from Canada, the United States, and Israel, the discussions (later published) laid bare several irreconcilable issues on which the representatives of the two peoples of different generations could not agree. Despite the obstacles to reconciliation, the organizers Potichnyj and Aster remained convinced of similarities between the Ukrainian and Jewish historical experiences. It was that conviction tempered by reality that prompted Potichnyj and Aster to characterize the historical experience of Jews and Ukrainians as "two solitudes."

The concept of "two solitudes" defined the next quarter-century of Jewish-Ukrainian dialogue. Nevertheless, the published McMaster conference proceedings opened up a range of themes and topics that had been previously overlooked because of the generally russocentric approach of most North American and Israeli scholars who deal with the history of Russia and the Soviet Union. The dialogue initiated at the McMaster conference showed that diaspora thinkers could help reconcile the historical narratives of the two peoples by going beyond the existing ethnocentric stereotypes of the Jewish or Ukrainian Other. Particularly important in this regard was the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, which afforded access to long-closed archival material housed in Ukraine and Russia. That practical reality, combined with the depoliticization of historical studies and the acceptance of new research methodologies (post-colonial theory), has provided a positive intellectual atmosphere for the current Ukrainian-Jewish dialogue.

Ukrainian diasporan impact on Ukraine

The impact of the Ukrainian diaspora on Ukraine and the Jewish diaspora on Israel has played itself out in various spheres, whether in civic life, economic relations, religion, culture, or education. The intensity and effectiveness of the impact in any one of these spheres has depended on the political situation in the ancestral homelands and the degree to which they have been receptive to outside influences.

Civic and economic life

The first wave of pre-World War I immigrants in North America remained in close contact with their families and villages in western Ukrainian lands. That relationship was primarily economic in nature. Some immigrants returned home (in some cases more than once) in the years before World War I, bringing with them their savings in order to buy land; most, while remaining abroad, sent home a portion of their earnings to their parents or wives. These remittances increased the availability of capital in rural villages, helping to improve local economic conditions, although at the same time driving up the price of land.

While financial assistance to individual families in Ukraine continued during the interwar years, fraternal and civic organizations carried out community fund-raising campaigns to assist political and economic causes in the homeland. Examples of financial support included emergency funds sent in 1920 to maintain the offices of the West Ukrainian National Republic's Vienna-based government-in-exile; and aid sent in the 1930s by the American-based United Ukrainian Organizations to support Ukrainian charitable, educational, and political institutions in Polish-ruled Galicia. When, at the close of World War II, the Soviet regime closed off Ukrainian lands to outside assistance, diasporan organizations directed their attention elsewhere, whether assisting refugees from Displaced Persons camps in Europe to immigrate to the United States and Canada, or, as in the case of political émigrés based mainly in post-war Germany and Great Britain, cooperating with Western counter-intelligence services to revive the anti-Soviet insurgency movement in Ukraine.

Until the late 1980s, the only concrete relations with the ancestral homeland were limited to cultural ties implemented by leftist-oriented Ukrainian diasporan groups (most especially in Canada), which since the 1930s had been actively courted by the Soviet Union. Beginning in the 1960s, a select number of anti-nationalist Canadian and American leftists were allowed to visit Soviet Ukraine, and some were even critical of Soviet policies, whether toward the Ukrainian language or the decision to launch the Soviet-led invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968.

In many ways, the Ukrainian diaspora's ability to have any significant impact on the ancestral homeland began only on the eve of and after Ukraine gained its independence. In the late 1980s diasporan Ukrainians began to visit in increasing numbers Soviet Ukraine, where they gave moral and financial support to democratic movements like Rukh, which at the time were in the forefront of the drive for independent statehood. After independence was achieved, several diasporan Ukrainians "returned home" to lend their professional expertise as advisers to the new government and as founders or as leading participants in a wide range of non-governmental organizations trying to assist Ukraine in its transition to a market economy and a civic society based on democratic principles. A certain number of economically successful American and Canadian Ukrainians felt that they, too, might be able to help — combining their Ukrainian patriotic feelings with their business interests. Sooner or later, however, most diasporan investors pulled out of a country that was unable to provide a secure environment for Western-style business practices.

Religion

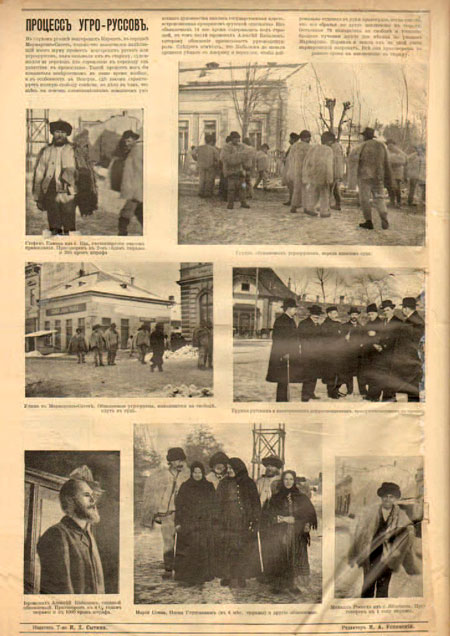

Religion and church life have always been an important component of diasporan life, but their impact on the homeland has been limited. During the pre-World War I first wave of immigration, a "return-to-Orthodoxy" movement became widespread among North America's Ruthenian Greek Catholics. That development soon had an impact on the Ukrainian homeland. Some immigrant "converts" to Orthodoxy who returned home brought funds and publications to propagate their convictions among Greek Catholic relatives and friends. The result was another "return-to-Orthodoxy" movement, this time in the European homeland, and often precisely in those villages in southern Galicia and Transcarpathia to where the "Americans" had returned. Greek Catholic leaders and priests in these western Ukrainian lands were so alarmed that they called on the Austro-Hungarian authorities to intervene. The government's response was to hold several so-called treason trials (1905, 1913, 1917) of Orthodox believers, many of whom were found guilty and imprisoned for their faith. Yet the Orthodox movement was not destroyed and even grew after World War I, when these lands became part of Poland and Czechoslovakia.

Because of war, political changes, and in particular repressive Soviet rule, any diasporan religious impact on the homeland was not really possible until the waning years of the Soviet Union. Finally, the outlawed Ukrainian/Greek Catholic and Ukrainian Autocephalous Orthodox churches were legally restored in the late 1980s, and within a few years the hierarchies of those churches (until then in Rome and in New Jersey) returned permanently to Ukraine. Since the 1990s, both the Ukrainian Catholic and Autocephalous Orthodox diasporan communities have been particularly generous in raising funds to build new seminaries and churches in Ukraine, while many young priests — born and educated in the diaspora — have gone to Ukraine on a temporary or permanent basis to help train a new generation of priests and religious leaders. The most outstanding example of diasporan influence has been the reopening in western Ukraine of the pre-war Lviv Theological Academy, which in 2006 was transformed into the Ukrainian Catholic University. Headed and largely staffed by Ukrainians and non-Ukrainians from the West, Lviv's Ukrainian Catholic University has successfully implemented standards similar to those in North American universities, including English as well as Ukrainian as the language of instruction, and programs in Jewish studies made possible by support from the Canadian philanthropist James Temerty.

Education and scholarship

Independent Ukraine has allowed and, at times, encouraged diasporan assistance and involvement in its educational and scholarly institutions. Since the 1990s, the administrators of two revived historic schools of higher learning, the Kyiv-Mohyla Academy and the Ostroh Academy, solicited and received substantial funding from Ukrainian philanthropists in North America, which helped to make possible their transformation into universities. Both employ professors from North America and use English, alongside Ukrainian, as a language of instruction.

North American centers of Ukrainian studies, especially those at the University of Alberta, the University of Toronto, and Harvard University, have since the 1990s established a variety of exchange fellowships, publication projects, and joint institutions together with Ukrainian universities and several institutes at the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine in Kyiv. In an effort to raise the overall intellectual climate in Ukraine, one enterprising diasporan scholar from Harvard (George G. Grabowicz) established a publishing house in Kyiv, which, among other things, produces a Ukrainian-language journal (Krytyka) modelled on the New York Review of Books. Although not associated with a university, other diaspora activists have created with assistance from the Canadian government the Canadian-Ukrainian Parliamentary Program whose goal is to expose annually about thirty to forty young Ukrainians to democratic governing practices in the West.

Click here for a pdf of the entire book.