Chapter 10.4: "Jews and Ukrainians: A Millennium of Co-Existence"

Jews and Ukrainians: A Millennium of Co-Existence is an award-winning book that explores the relationship between two of Ukraine’s most historically significant peoples over the centuries.

In its second edition, the book tells the story of Ukrainians and Jews in twelve thematic chapters. Among the themes discussed are geography, history, economic life, traditional culture, religion, language and publications, literature and theater, architecture and art, music, the diaspora, and contemporary Ukraine before Russia’s criminal invasion of the country in 2022.

The book addresses many of the distorted stereotypes, misperceptions, and biases that Ukrainians and Jews have had of each other and sheds new light on highly controversial moments of Ukrainian-Jewish relations. It argues that the historical experience in Ukraine not only divided ethnic Ukrainians and Jews but also brought them together.

The narrative is enhanced by 335 full-color illustrations, 29 maps, and several text inserts that explain specific phenomena or address controversial issues.

The volume is co-authored by Paul Robert Magocsi, Chair of Ukrainian Studies at the University of Toronto, and Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern, Crown Family Professor of Jewish Studies and Professor of History at Northwestern University. The Ukrainian Jewish Encounter sponsored the publication with the support of the Government of Canada.

In keeping with a long literary tradition, UJE will serialize Jews and Ukrainians: A Millennium of Co-Existence over the next several months. Each week, we will present a segment from the book, hoping that readers will learn more about the fascinating land of Ukraine and how ethnic Ukrainians co-existed with their Jewish neighbors. We believe this knowledge will help counter false narratives about Ukraine, fueled by Russian propaganda, that are still too prevalent globally today.

Chapter 10.4

Jewish diasporan impact on Ukraine

Civic and economic life

During the first three decades of the twentieth century, Jewish immigrants in the United States and Canada sent a part of their small savings to relatives in Russian-and later Polish-and Soviet-ruled Ukraine. The remittances significantly helped Jewish families (and Ukraine's economy in general), especially in the 1920s after the human and material destruction of World War I, civil war, pogroms, and the famine of 1921. All these events resulted in the devastation of community life and Jewish economic well-being in former Russian-ruled Ukraine.

In response to these events, dozens of leftist organizations in the United States, Canada, and Argentina provided assistance to Jewish orphanages and schools, while religious organizations sent flour and goods as Passover gifts. Starting in 1924, the American Joint Distribution Committee (the Joint) established its Agro-Joint subdivision, which directly sponsored a program to resettle Jews on newly established collective farms in southern Ukraine and northern Crimea (see map 20). The Joint shipped hundreds of agricultural machines and tractors to these farming communities. By the early 1930s, the Joint had ceased its activities, and in the following decade the Soviet authorities designated the organization an agent of foreign espionage. To be associated with such an organization was tantamount to involvement in anti-Soviet state treason.

After 1941, however, when the United States and the Soviet Union became allies, Jewish-American organizations lobbied effectively for the establishment of the U.S. government Lend-Lease program, which allowed military equipment, food, and clothing to be shipped to the Soviet Union. This short-lived wartime period of American-Soviet rapprochement came to a halt after 1945, in large part because of Soviet expansionist ambitions in central Europe and the growing xenophobia and chauvinism that characterized the last years of Stalinist rule.

Throughout the subsequent Cold War period, direct involvement of any diasporan Jewish organization was considered by the Soviet Communist party leadership and security organs as an intrusion into the country's domestic affairs. Beginning in the 1960s, there were sporadic encounters between Jewish tourists coming to visit a local synagogue in the few open Soviet cities, although these were closely monitored by undercover security agents who were aware that some of these visitors represented diaspora Jewish organizations. The Soviet authorities went to great lengths to create a Potemkin village for its few foreign visitors from the West, often introducing them to Jewish community activists who claimed that religious-oriented Jews were "not persecuted," that Soviet Jews in general "lack nothing," and that they did not need any foreign help or support.

With the ascent to power of the reformer Michael Gorbachev in 1985, Soviet Cold War policies gradually came to a halt. Within a few years visitors and representatives from major Israeli, European, and North American Jewish organizations could travel freely to Soviet Ukraine. Organizations such as the Joint were allowed to establish dozens of social-welfare centers called Hesed (Kindness), which distributed food parcels to the needy, provided free canteens for elderly Jews, assisted Jewish World War II veterans, and funded local community-building initiatives throughout Soviet Ukraine. The Joint was also instrumental in co-sponsoring various social-relief initiatives of the VAAD (Association of Jewish Organizations and Communities of Ukraine), which had its own wide network of social workers.

Jewish religious organizations of North America and Israel were particularly helpful in recreating community infrastructures and using them to extend social relief, first and foremost to the elderly who were caught unprepared during the initial stages of the transition to capitalism in the early 1990s, a transition marked by steep inflation and widespread corruption. Private American and Israeli sponsors assisted rabbinic leaders in establishing in Odessa the largest Jewish orphanage in Europe. Several diasporan organizations, such as the World Jewish Congress, Claims Conference, and the Joint, lobbied to help local Jewish communities reclaim community real estate confiscated by the Soviets. As a result, the governments of Soviet and later independent Ukraine returned more than a dozen synagogues to Jewish religious organizations.

Following the collapse of the Soviet Union, remittances from Jews living in Israel and North America were again allowed to be sent to relatives in Ukraine. Many Jewish entrepreneurs from New York, Los Angeles, Toronto, Jerusalem, Tel Aviv, and London set out for Ukraine, seeking to invest in newly privatized business enterprises, real-estate ventures, and other local economic initiatives. Most of these businessmen were former Soviet citizens from Ukraine, well aware of the legal vagaries and obstacles for conducting business in a post-Communist state. By the late 1990s, however, most diasporan entrepreneurs had become disappointed with the slow turnover of their investments, or they were squeezed from ownership and co-ownership by local competitors. As a result, many withdrew from Ukraine and from further participation in the country's economic life. Among the exceptions were diasporan Jews who invested in real estate (mostly Americans) and those (mostly Israelis) who established networks of small stores throughout Ukraine.

Religion

Jews from Ukraine have traditionally been concerned with the religious status of their brethren in the homeland. Beginning in the 1930s, sending religious literature from the West to the Soviet Union was tantamount to implicating the recipients in acts of religious propaganda, something that was penalized as a major offense against the atheist Communist regime. Gradually, however, Jewish religious works did again reach Soviet Ukraine. In the 1960s, tourists from the United States and Canada smuggled books in Russian that contained religious or political messages, including such novels as Exodus. Messengers of the Habad trend of Hasidism were appointed to serve as clandestine leaders among the observant Soviet Jews, helping to celebrate Jewish holidays, provide religious advice, and make available kosher food.

Once the Gorbachev reform era brought the Cold War to an end, dozens of rabbinic leaders from North America and Israel arrived in Ukraine, first as temporary messengers (shlikhim) and then as permanent residents. Together with local Jewish religious societies, they reclaimed abandoned or confiscated synagogues, established community infrastructures, and helped Ukraine's Jews start a religious life from scratch. American-and Israeli-based organizations, such as those of the Habad, Skvira, Karlin-Stolin, Munkatsch, and Bratslav Hasidim, were particularly active in bringing the religious dimension of Jewish culture back to the Jews of Ukraine, especially to the places where the groups traced their origins: Dnipropetrovsk, Kyiv, Uman, Berdychiv, and Mukachevo. In general, the diasporan Hasidim were much more successful than the Litvaks (non-Hasidic) Jews. Hence, what some observers have called the rabbinic revolution in Ukraine was in fact a Hasidic revolution. Despite their ultra-Orthodox approach and various restrictions against the secular sphere, Hasidic groups were more open to what Judaism calls kiruv: attracting non-observant Jews to tradition. This is in sharp contrast to the non-Hasidic Litvaks, who were more interested in hizuk: strengthening knowledge and beliefs among those who are already within the tradition.

Several wealthy American and Canadian Jews as well as the Israeli-based Mizrachi (national-religious) movement sponsored the arrival in Ukraine of non-Hasidic emissaries, who established themselves as rabbinic leaders in several large cities such as Kyiv and Odessa. In a real sense, their presence reflected the "diasporization" of Ukraine's Jewish cultural, religious, and political life. The impact of these new rabbinic leaders on the survival of the post-1991 Ukrainian-Jewish community cannot be overestimated.

Education and scholarship

The Jewish diaspora has also had an impact on education and scholarly activity in the homeland. In the wake of the Bolshevik Revolution and the implementation of Communist-inspired and atheistic ideology, after 1920 Jewish studies almost entirely disappeared from Soviet research and higher educational curricula. Hence, diasporan organizations could not contribute to the development of Jewish educational institutions or scholarship in Soviet Ukraine.

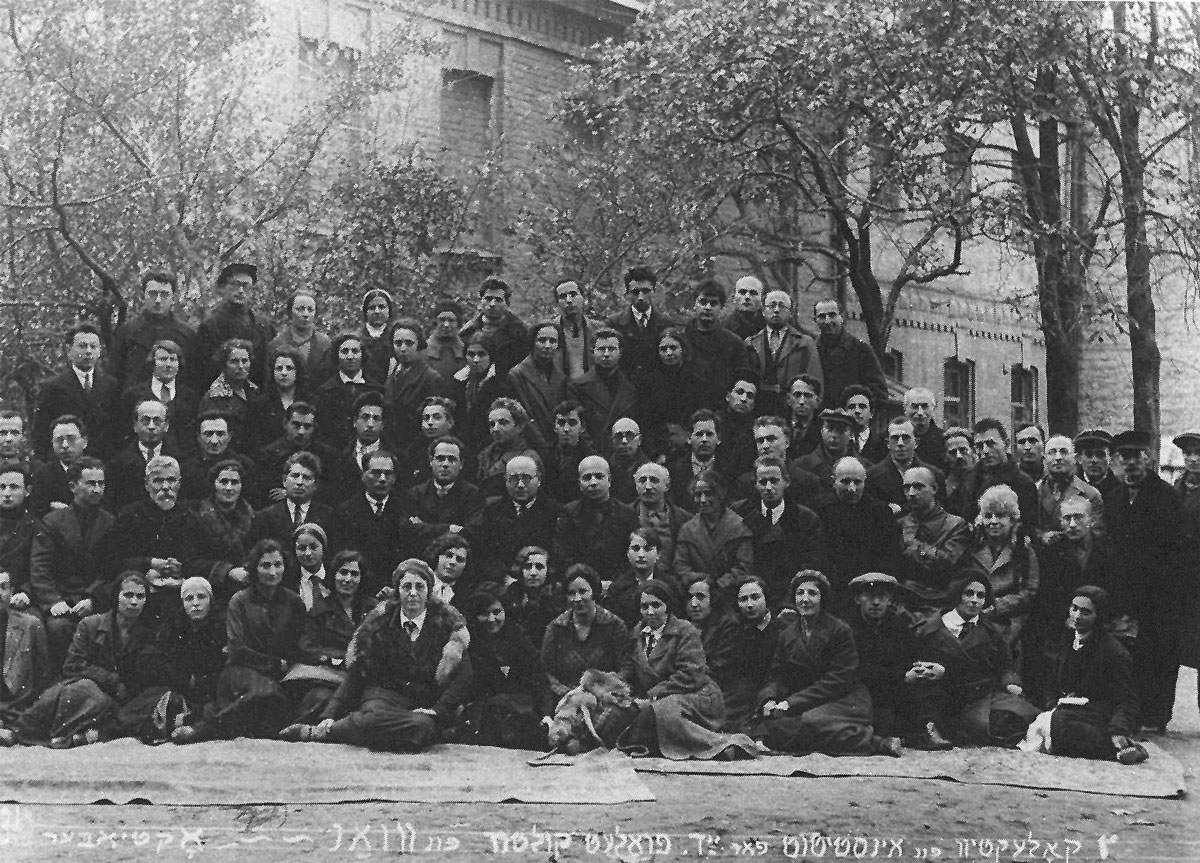

This situation changed for a while during the period of national communism that took place in earnest after 1925. In particular, leftist Jewish organizations in Buenos Aires, Paris, Johannesburg, New York, and Montreal sent publications and newspapers to the newly established Institute of Jewish Proletarian Culture in Kyiv. With the change in Soviet policy after 1928, foreign cultural exchanges were soon forced to cease. Subsequently, Jewish organizations abroad still tried to help Soviet scholars and cultural activists, although this entailed great risks for the recipients. For example, it was suspected ties with the West that led to the arrest in 1948–1950 of several Yiddish poets and scholars, who were accused of spying against the Soviet Union through contacts with organizations such as the American Joint Distribution Committee. In effect, during the Cold War contacts between Ukrainian scholars in Soviet Ukraine of Jewish descent with diaspora organizations were practically impossible.

The situation changed again in the late 1980s during the Gorbachev era. At that time, the Israeli-based Liaison Bureau (Lishkat ha-Kesher), which promoted emigration, acted as a foil for a diplomatic mission, while the Jewish Agency for Israel (Sokhnut) sent emissaries even before the Israeli ambassador was accredited to Ukraine. Lishkat ha-kesher helped establish the so-called ulpans, which provided intensive Hebrew-language courses for adults interested in emigrating (making aliyah) to Israel. In effect, the ulpans and their instructors became a window into Israel, providing a basic introduction to Israeli culture, politics, and society.

In the 1990s, after half a century, the American Joint Distribution Committee (the Joint) re-established itself in Ukraine. Since then it has invested heavily in the development of local educational and scholarly institutions. For example, it has generously supported the efforts of the Ukrainian Center for Jewish Education to promote Sunday schools and day schools, the short-lived Jewish Studies program at the private International Solomon University in Kyiv, several Holocaust Studies centers, and dozens of libraries that make available diaspora-published books (mostly in Russian) to public and Jewish libraries. Finally, the Joint has funded travel of Ukraine's Jewish leaders to seminars in Israel, Europe, and the United States. For some time, there existed rivalry over goals between the Joint, which supports the rebirth of local community life, and Sokhnut, which is opposed to the idea of helping the diaspora at the expense of emigration to Israel. Eventually, however, Sokhnut modified its views when the importance of the new educational and cultural programs for preserving Jewish life in Ukraine became clear.

After Ukraine became independent, Israeli and North American foundations and educational institutions became major sponsors of new educational and research projects, including funding for North American Jewish professors to teach or give lectures at various Ukrainian educational establishments. Analogously, Israeli-based teacher-training institutions invite Jewish teachers and university lecturers from Ukraine to spend up to two years in Israel for specialized training on the premise that they will return home and work in Jewish educational establishments. Among other diaspora organizations that have recently established centers in Ukraine are the Conservative Movement teaching institution Midreshet Yerushalaim, with its own school in Chernivtsi (one of Ukraine's best Jewish day schools in the 1990s), and the Hasidic Habad organization, with its Jewish schools operating in many cities throughout Ukraine, the largest of which (with nearly 900 students) is in Dnipropetrovsk.

Of particular importance to Jewish scholarship is the Oriental Studies Institute at the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine, re-established in 1991 at the initiative of a Ukrainian-American professor from Harvard, Omeljan Pritsak. This body has had several scholars and graduate students whose main focus is Hebrew manuscripts. By the beginning of the twenty-first century, a whole host of diasporan-and Israeli-based bodies (the Rothschild Foundation in Europe and Israel, the Nevzlin Center at Hebrew University, Project Judaica sponsored by Conservative Jewish organizations in the United States, and the Ukrainian Jewish Encounter in Canada) have assisted newly emerging programs at leading Ukrainian universities, such as Mohyla Academy in Kyiv and the Ukrainian Catholic University in Lviv. Still other diaspora institutions have lent support to specific programs, whether archival research (sponsored by Project Judaica and the Holocaust Museum in Washington, D.C.) or the Claims Conference, which finances the preparation of inventories to help in the restitution of former Jewish community property confiscated by the Soviets.

Click here for a pdf of the entire book.