Chapter 11.2: "Jews and Ukrainians: A Millennium of Co-Existence"

Jews and Ukrainians: A Millennium of Co-Existence is an award-winning book that explores the relationship between two of Ukraine’s most historically significant peoples over the centuries.

In its second edition, the book tells the story of Ukrainians and Jews in twelve thematic chapters. Among the themes discussed are geography, history, economic life, traditional culture, religion, language and publications, literature and theater, architecture and art, music, the diaspora, and contemporary Ukraine before Russia’s criminal invasion of the country in 2022.

The book addresses many of the distorted stereotypes, misperceptions, and biases that Ukrainians and Jews have had of each other and sheds new light on highly controversial moments of Ukrainian-Jewish relations. It argues that the historical experience in Ukraine not only divided ethnic Ukrainians and Jews but also brought them together.

The narrative is enhanced by 335 full-color illustrations, 29 maps, and several text inserts that explain specific phenomena or address controversial issues.

The volume is co-authored by Paul Robert Magocsi, Chair of Ukrainian Studies at the University of Toronto, and Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern, Crown Family Professor of Jewish Studies and Professor of History at Northwestern University. The Ukrainian Jewish Encounter sponsored the publication with the support of the Government of Canada.

In keeping with a long literary tradition, UJE will serialize Jews and Ukrainians: A Millennium of Co-Existence over the next several months. Each week, we will present a segment from the book, hoping that readers will learn more about the fascinating land of Ukraine and how ethnic Ukrainians co-existed with their Jewish neighbors. We believe this knowledge will help counter false narratives about Ukraine, fueled by Russian propaganda, that are still too prevalent globally today.

Chapter 11.2

Israel and Ukraine — Jews and Ukrainians

The post-1991 authorities in independent Ukraine chose to rid themselves of yet another troubling aspect of the Communist past: the vicious Kremlin-orchestrated anti-Zionism campaign and public humiliation of Israel as a Cold War puppet of the United States. Already in the fall of 1991, Ukrainian government leaders held negotiations with various Jewish NGOs, including the World Zionist Organization. Then, on 25 December 1991, Israel became one of the first countries to recognize Ukraine as an independent country, with which it proceeded to establish diplomatic relations. Ukrainian government officials and high-ranking diplomats publicly and privately expressed genuine interest in establishing strong political links and economic ties with Israel, especially in the agricultural, high-tech, and military spheres. The prominent Ukrainian writer and liberal-minded journalist Yurii Shcherbak became Ukraine's first ambassador to Israel. At one of the first art shows at the Ukrainian Embassy in Tel Aviv (1993), a curious photograph on display epitomized the new atmosphere: Ukrainian Cossacks eating Passover matzo as a kind of cultural symbol of the elimination of inter-ethnic prejudice.

Less than a year after the establishment of diplomatic relations, Israel welcomed a Ukrainian parliamentary delegation, and since the state visit of President Kravchuk in January 1993, all four of his successors (Leonid Kuchma, Viktor Yushchenko, Viktor Yanukovych, and Petro Poroshenko), as well as several of the highest government leaders in Ukraine, have gone to Israel on official visits. As the result of growing cooperation in the political and business spheres, the trade between Ukraine and Israel in the period from 2006 to 2012 doubled, reaching $950 million (U.S.) annually.

Ukraine's understanding of its Jewish past

Since 1991, many cultural, artistic, and educational institutions in Ukraine have chosen to emphasize their sympathy for the Jews and respect for Jewish culture. In 1992 the Kyiv State Opera introduced Giuseppe Verdi's Nabucco into its repertoire and had the ancient Jews in Babylonian exile dressed as Ashkenazic Jews from the Pale of Settlement That same year, the Ivan Franko State Ukrainian Dramatic Theater in Kyiv staged the play Tevye-Tevel, based on the writing of Sholem Aleichem and with Ukraine's leading actor, Bohdan Stupka, as Tevye the Milkman. In 2001 the Kyiv State Opera added to its repertoire Moisei (Moses), by Myroslav Skoryk, based on Ivan Franko's pro-Zionist epic poem that is built on a direct parallel between the biblical Jews and modern-day ethnic Ukrainians.

Discussion of the parallels between Ukrainians and Jews, previously avoided by both sides as inappropriate, now became part of the new inter-ethnic climate. Ivan Dzyuba, the former dissident and from 1992 the country's minister of culture, defined Jews and Ukrainians in post-colonial terms as "two victims of history and of regimes which suppressed freedom." Former Jewish and ethnic Ukrainian dissidents who became influential in post-Communist Ukraine's political life (Josef Zissels, Semen Gluzman, Myroslav Marynovych, Zynovii Antonyuk, and Yevhen Sverstyuk) published their memoirs as a joint book project. The new atmosphere encouraged writers of Ukrainian and Jewish background such as Dmytro Pavlychko, Ivan Drach, Naum Tykhyi, and Abram Katsnelson to publish works they had written (but not published) in Soviet times, emphasizing mutual sympathy between Jews and Ukrainians.

Israel and independent Ukraine

Following the political "rehabilitation" of Israel at Ukraine's government level, various Ukrainian intellectuals with strong nationalist leanings looked favorably on the Israeli nation-building experience, which they saw as a model for state-building in post-1991 Ukraine. In their attempts to revive Ukrainian culture and statehood, they could not overlook the fact that in the fifty years of its existence since 1948, Israel had managed to rejuvenate the Hebrew language and culture, build an efficient agricultural sector, and achieve a per capita GDP on a par with many European countries. In the words of Larysa Skoryk, president of the government-sponsored Ukraine-Israel Society: "The modern history of re-established Israel is for the young Ukrainian state an eloquent example of how to strive for, gain, build up, and preserve state independence — a prerequisite for the greatness, freedom, and indestructibility of the nation."

Hence, it was not long before the dialogue between ethnic Ukrainians and Jews was elevated to a dialogue between two state-based nations. Parallels between Ukraine and Israel changed the meaning of a famous line by the nineteenth-century Ukrainian poet Lesya Ukrayinka: I ty borolas yak Izrayil, Ukrayino moya (And you, my Ukraine, also fought like Israel). What had been a metaphor for landless ethnic Ukrainians and stateless Jews (Izrayil) had now become a symbolic parallel between independent Ukraine and the state of Israel.

Books that explored the differences and similarities in language policies, historical experiences, public institutions, national self-identification, and forms of nation-building in Israel and Ukraine entered the mainstream scholarly discourse in Ukraine. For example, Orest Tkachenko of the Potebnya Institute of Linguistics at the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine portrayed Hebrew as an example of the "linguistic firmness" (movna stiikist) which assured the preservation of the Jewish tradition. His point was that linguistic policy in Israel should serve as a model for the revival of the Ukrainian language and culture in Ukraine.

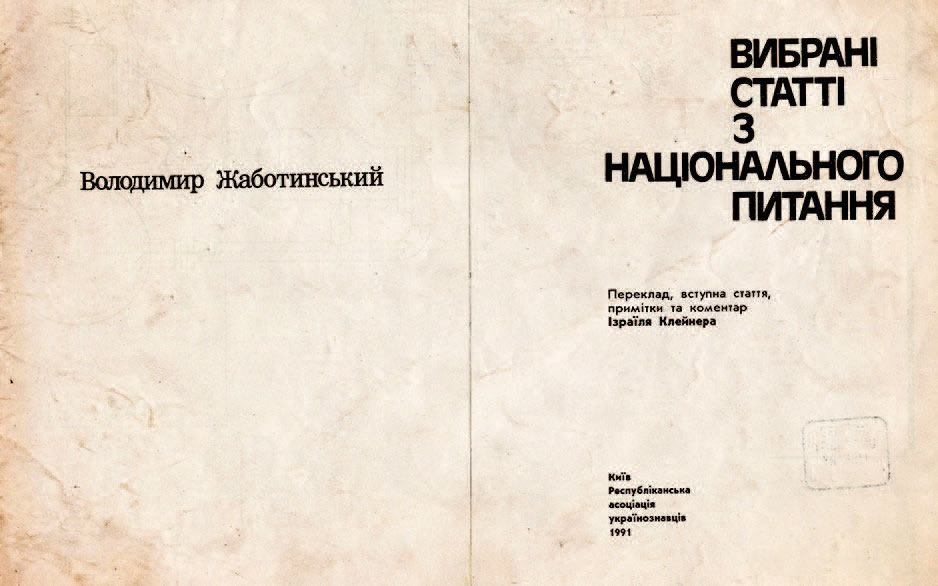

The figure of Zeev/Vladimir Jabotinsky, the Odessa-born Zionist, was at the epicenter of this new discourse. Both before and after his death in 1940, Jabotinsky had been a persona non-grata in the Soviet Union, where his very name was unmentionable. Through the efforts of his Ukrainian admirers, by the late 1990s Jabotinsky was appropriated by many Ukrainian politicians and intellectuals who admired his long-standing vociferous criticism of russification, his opposition to Jewish assimilation, his defense of the uniqueness of the Ukrainian language and culture, and his staunch support of Ukrainian national strivings. He was now hailed as a great friend of the Ukrainian people, some calling him an "Apostle of the Nation" comparable to Vyacheslav Lypynskyi.

Ukraine-Israeli interaction

Ukraine-Israeli relations underwent further transformation. Following an official visit to Jerusalem in mid-2000 by the mayor of Kyiv, other Israeli cities, including Haifa, Rishon Le-Zion, and Beer Sheva, signed agreements on cultural exchange and cooperation with Kharkiv, Dnipropetrovsk, Chernivtsi, and a number of other Ukrainian cities.

Because of the exceptionally rich Jewish past in Ukraine, tourism has become one of the key points of political and socio-cultural rapprochement between the two countries. In the period from 2007 to 2010, on average more than 60,000 Israelis visited Ukraine, while at the same time the figures for Ukrainians visiting Israel was between 130,000 and 150,000 annually. Since then the tourist flow to Israel has been given a further boost thanks to Israel's decision to introduce in 2010 visa-free entry for citizens of Ukraine. For Ukrainian Christians, the most important sites in Israel are Bethlehem and Jerusalem. Ukraine, meanwhile, became one of the major places of pilgrimage for observant (above all Hasidic and other Orthodox) Jews worldwide. This is particularly the case since the founding fathers of several branches of Hasidism preached, established their courts, and were buried in what is today independent Ukraine.

Among the most important pilgrimage destinations are the burial sites of legendary Hasidic leaders, which include Hadyach (for Shneur Zalman of Lyady, the founder of the Habad Hasidim); Medzhybizh (for the legendary founder of Hasidism, Yisrael ben Eliezer [the Baal Shem Tov]); the Sadhora suburb of Chernivtsi (for Rabbi Friedman, known as Yisrael of Ruzhin); Berdychiv (for Levi Yitshak); Kyiv (for the Twersky dynasty of Hasidic masters); Shepetivka (for Rabbi Pinhas of Korets, the predecessor and father of the founders of the Shapira Hasidic dynasty of printers); Vyzhnytsya (for Menahem Mendel Hager, founder of the Vizhnitz dynasty of Hasidim); Bratslav (for the scribe of Rabbi Nachman of Bratslav); Zhydachiv (for Rabbi Tsvi Hirsch); and Mukachevo (for Rabbi Hayim Elazar Shapira).

Despite the popularity of all these sites, none rivals Uman, with its burial place of the Rabbi Nachman of Bratslav (d. 1807). A person of great psychological insight with an aphoristic mind and a formidable imagination, Rabbi Nachman preached to his followers that it would be a special merit (zkhus) to pray during the High Holidays in his presence, and that it would be even more significant for them to pray at his grave once he was no more in this world. Not without a dint of messianic sensibility, he maintained that his own grave would possess the power of a magical charm (segulah) — so much so that, when those who prayed at his grave went to the other world, he would emerge to pull them out from Gehenna. In this rather witty manner, Rabbi Nachman assured his posthumous fame: pilgrimages to his grave have been going on for two hundred years.

Whether or not religious Jews believe Rabbi Nachman's prediction, many (even from far beyond the circle of the Bratslav Hasidim, today based in Tzfat, Israel) visit his grave during the High Holidays of the Jewish New Year each autumn. The numbers are quite astounding: whereas in 1994 about three thousand pilgrims visited Uman, since 2012 on average between twenty to thirty thousand arrive from North America, Australia, Israel, several western European countries, and Russia. Although their main purpose is to pray at the gravesite, the pilgrims at the same time have contributed significantly to Uman's local insfrastructure. In order to accommodate their needs, a new synagogue for four thousand people was built, the gravesite was renovated, and canteens for kosher food and stores to sell Judaica artifacts and prayer books were set up. The pilgrims who arrive in Uman represent the entire spectrum of Judaism — from Bratslav and other Hasidim of European origin to Eastern-rite Jews from Morocco, Yemen, and central Asia, and Sephardic Jews from throughout the diaspora. Among them are modern and ultra-Orthodox Jews, observant and semi-observant Jewish hippies, and unaffiliated, curious younger Jews mostly from the other republics of the former Soviet Union. Accommodating such numbers is a major feat for an otherwise out-of-the-way, provincial town like Uman. Ukrainian militia and at times policemen from Israel have provided security, while Hebrew-language signs are displayed in the center of town indicating major urban services and directions. Not surprisingly, Uman's economy revives significantly during the autumn days, reminding one of the bustling trading town that it was in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Now, however, ethnic Ukrainians are the sales persons and Jews the buyers. From time to time, there have been minor criminal offenses, including brawls between ethnic Ukrainians and some of the pilgrims. There have even been calls by a small local racist group to banish the Hasidim from Uman. But such problems have not deterred the pilgrims, most of whom rent apartments from local residents. In effect, none of the inevitable problems between tourists and locals anywhere in Europe are sufficient to disrupt the prolonged Jewish New Year festivities which each September reconfirm the mutually beneficial economic interests of Uman's Ukrainians and visiting Jews.

Visions of the past

Despite the sympathy for rapprochement with Jews on the part of Ukraine's political and intellectual elites, the integration of Jewish history and culture into Ukraine's educational system has been sorely wanting. For example, most college texts continue, as in Soviet times, to present a historical discourse in which Jews are completely absent. Therefore, random references to the 1919 pogroms or the Holocaust that do appear are puzzling to students who wonder: Why did so many Jews live on Ukrainian lands? Where did they come from and what did they do for centuries? Why is Ukraine historically and culturally still considered so important for Jews?

There are a few reputable intellectuals in Ukraine (Yaroslav Hrytsak, Taras Voznyak, Yurii Shapoval, and Nataliya Yakovenko) who do touch upon Jewish issues in their specialized monographs. Not so, however, for the authors of university textbooks. In the best-case scenario, the textbooks reflect an ethnocentric vision of Ukraine that allows little, if any, place for non-ethnic Ukrainians, whether Crimean Tatars, Poles, Jews, or others. In the worst-case scenario, they simply continue the tradition of Soviet textbooks, which sought to downplay ethnicity and to emphasize instead the role of the working classes while presenting Ukraine as a land inhabited by a homogeneous Slavic people friendly to their Russian "Elder Brother."

Important exceptions to the above scenario are local histories. Since these are not subject to bureaucratic pressure from the central authorities in Kyiv, historians in places that traditionally had large and influential Jewish communities (Drohobych, Hulyaipole, Medzhybizh, Volodymyr-Volynskyi, Zaporizhzhya, among others) have successfully incorporated into their narratives rich and reliable descriptions of Jewish economic, religious, and literary achievements as well as accounts of atrocities during the World War II period. Chernivtsi and Lviv both set a new standard for high-quality local history writing; several new histories adopt the multicultural approach, interweaving the Jewish, German, Romanian, and Ukrainian experiences into a single narrative about these main centers of historic Bukovina and Galicia.

New forms of antisemitism

The rapprochement between Jews and Ukrainians and between Ukraine and Israel since 1991 has occurred in a mostly benign atmosphere. Nevertheless, there remain challenges, and it was not long before new forms of antisemitism and anti-Zionism took shape. For example, the Interregional Academy of Personnel Management (MAUP), a privately funded non-government college established in Kyiv in 1989, became the leading (perhaps the only) center of institutionalized antisemitism. Through its conferences and serial publications (Personal and Personal plyus), the MAUP leadership launched a series of vociferous and often vicious attacks on Jews and against Israel.

The new antisemites revived the entire arsenal of ignominious stereotypes. They continue to see Jews as supporters of Menahem Mendel Beilis in the alleged 1911 ritual murder of a Christian boy; Jews as organizers of the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution; Jews as opponents of Ukrainian culture who helped orchestrate the Great Famine of 1933; and Jews as the main instruments of independent Ukraine's transformation into a puppet of international Zionist capital after 1991. The newspaper Silski visti, largely supported by MAUP and with a circulation of over half a million regularly published hate-mongering antisemitic diatribes. MAUP even awarded an honorary academic degree to a renowned antisemite and neo-Nazi sympathizer, the American Ku-Klux-Klan Knight David Duke. Despite these and other provocative activities, including the republication of classic antisemitic works (among others, the slanderous Book of the Kahal, 1869), MAUP's reputation was undermined following criticism by former students and a well-publicized denunciation in 2005 by the then president of Ukraine, Viktor Yushchenko.

Subsequently, antisemitic statements made their way, albeit slowly, into mainstream Ukrainian politics with the rise of the Svoboda (Freedom) and later Pravyi sektor (Right Sector) parties. Capitalizing on the dissatisfaction of many people with Ukraine's economic crisis, its unrealized reforms, and the ongoing corruption among the political elites, Svoboda's leader, Oleh Tyahnybok, responded by presenting a populist solution, that is, to create internal enemies, Russians and Jews, who could then be blamed for ruining the country. Among the targets to criticize were corrupt oligarchs of Jewish origin and pro-Russian-oriented politicians like as Dmytro Tabachnyk (of mixed Jewish-Russian descent), the controversial minister of education under ousted President Yanukovych.

The antisemitic political rhetoric of Tyahnybok and his supporters attracted the attention of the international media both in Russia and the West, most especially when the Svoboda party gained 7 percent of the vote (41 seats) in the 2012 parliamentary elections. Those elements, especially Putin's Russia, that were intent on undermining the protests on the Maidan in 2013–2014 hoped to achieve their goals by depicting the Svoboda and the Right Sector parties as the face of a post-Yanukovych "fascist" and "antisemitic" Ukraine. Regardless of the veracity of such claims, when new elections took place in October 2014 to Ukraine's 450-seat national parliament, the Svoboda party gained only six seats and the Right Sector a mere two — ironically one of which is held by a Jew.

While Ukraine's authorities have since independence made unprecedented efforts to create a positive atmosphere and foster inter-ethnic relations, the future of such rapprochement is not clear. Success will depend much more on internal political and socio-economic stability than on the continuing efforts of the parties involved to bring Ukrainians and Jews together, in order to help them understand one another beyond the distorted stereotypes that have traditionally viewed Jewish-Ukrainian relations only through the prism of mass violence and mutual animosity.

Click here for a pdf of the entire book.