Chapter 2.1: "Jews and Ukrainians: A Millennium of Co-Existence"

Jews and Ukrainians: A Millennium of Co-Existence is an award-winning book that explores the relationship between two of Ukraine’s most historically significant peoples over the centuries.

In its second edition, the book tells the story of Ukrainians and Jews in twelve thematic chapters. Among the themes discussed are geography, history, economic life, traditional culture, religion, language and publications, literature and theater, architecture and art, music, the diaspora, and contemporary Ukraine before Russia’s criminal invasion of the country in 2022.

The book addresses many of the distorted stereotypes, misperceptions, and biases that Ukrainians and Jews have had of each other and sheds new light on highly controversial moments of Ukrainian-Jewish relations. It argues that the historical experience in Ukraine not only divided ethnic Ukrainians and Jews but also brought them together.

The narrative is enhanced by 335 full-color illustrations, 29 maps, and several text inserts that explain specific phenomena or address controversial issues.

The volume is co-authored by Paul Robert Magocsi, Chair of Ukrainian Studies at the University of Toronto, and Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern, Crown Family Professor of Jewish Studies and Professor of History at Northwestern University. The Ukrainian Jewish Encounter sponsored the publication with the support of the Government of Canada.

In keeping with a long literary tradition, UJE will serialize Jews and Ukrainians: A Millennium of Co-Existence over the next several months. Each week, we will present a segment from the book, hoping that readers will learn more about the fascinating land of Ukraine and how ethnic Ukrainians co-existed with their Jewish neighbors. We believe this knowledge will help counter false narratives about Ukraine, fueled by Russian propaganda, that are still too prevalent globally today.

Chapter 2.1

The Historical Past

Of the 2,600 years of recorded history on the territory of Ukraine, the first two millennia witnessed the evolution of several civilizations focused southward toward the Black Sea and from there linked through the Bosporus and Dardanelles straits to the Aegean and Mediterranean worlds. This southward thrust was a reflection of the symbolic relationship between sedentary civilizations based along the shores of the Aegean and Mediterranean seas (Greek city-states, the Roman and Byzantine empires) and the nomadic-pastoral tribal peoples (Scythians, Sarmatians, Khazars, Polovtsians, Mongols, and Tatars) who set up polities on the steppe hinterland of Ukraine and southern Russia.

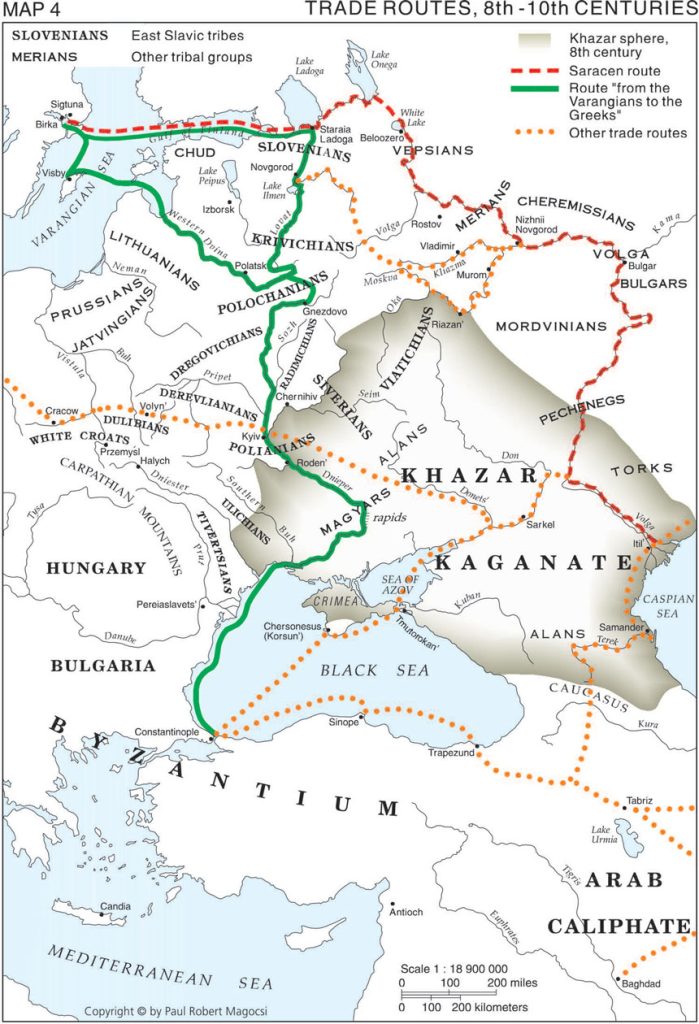

The relationship between Ukraine's sedentary and nomadic civilizations was based on trade and commerce. The nomadic-pastoral tribal polities extracted raw materials (agricultural products and human slaves) from the Ukrainian hinterland and oversaw trade from the Far East and Central Asia in exchange for manufactured goods and luxury items produced in the Aegean-Mediterranean world. Into this mix came at times other traders from the north, the most prominent of whom were Scandinavians known as the Varangian Rus'. Beginning in the ninth century CE, these Varangians mobilized the sedentary East Slavic tribes, and together they created a new polity known as Kievan Rus'. This marked the beginning of a process whereby a good portion of Ukrainian lands were gradually drawn northward and westward and integrated into the socio-economic and cultural networks of the rest of Europe north of the Alps.

Pontic and steppe civilizations

Greeks, Scythians, and Khazars

The first stage in Ukraine's historical evolution began about 650 BCE, when settlers from Greek city-states (especially Miletus and Megara) set up colonies along the northern shores of the Pontic, or Black Sea, including Tiras and Olbia at the mouths of the Dniester and Southern Buh rivers and Chersonesus and Theodosia in Crimea. About the same time, an Iranic tribal people known as Scythians arrived from the east and soon dominated the steppe hinterland. The Greek city colonies along the Black Sea served an intermediary function through which foodstuffs traded by the Scythians were sent on to the Aegean-Mediterranean world. This mutually beneficial symbiotic relationship was subsequently continued by other steppe-based tribal peoples (Sarmatians, Alans) and the Black Sea coastal cities, which took the form of an independent political entity (the Bosporan Kingdom, after 480 BCE) or of dependencies of the Roman Empire (after 63 BCE) and of the East Roman, or Byzantine, Empire (after the 520s CE).

Among the most influential of the nomadic tribal steppe polities was the Khazar Kaganate, or Khazaria, which came into being about 650 CE. Based north of the Caucasus Mountains in the lowlands between the Caspian Sea and Sea of Azov, Khazaria's sphere of influence extended northward across the open steppe encompassing what is present-day southern Russia (the lower Volga and Don river valleys) and central and southern Ukraine as far as the mouth of the Dniester River. Kyiv, for instance, was at the far northwestern edge of the Khazar sphere, while in the south Khazaria's sway ended at the Crimean Mountains, leaving the coastal cities of the Crimean peninsula under the hegemony of the Byzantine Empire.

For at least two centuries (650–850 CE), the Khazars kept peace among the various nomadic-pastoral peoples living in the steppe, which allowed them to control the commerce and trade from Central Asia and from the Arab world south of the Caucasus that passed through their territory toward the Black Sea trading cities and capital of the Byzantine Empire, Constantinople.

Among the merchant traders who reached the Khazar Kaganate were the Varangian Rus' from the north. Rus’-Khazar relations were based on the exchange of furs and slaves for silver, spices, and luxury items that Khazaria acquired from its farflung trading network. Experts in building vessels for transport along rivers and the open sea, the Varangian Rus' eventually bypassed the Khazars. They established a more direct route that began in their Scandinavian homeland (present-day eastern Sweden), crossed the Baltic Sea and Gulf of Finland, and proceeded via several rivers and lakes through Russia and Belarus until reaching the Dnieper River, which allowed them access to the Black Sea and the largest known commercial emporium of the time — Constantinople.

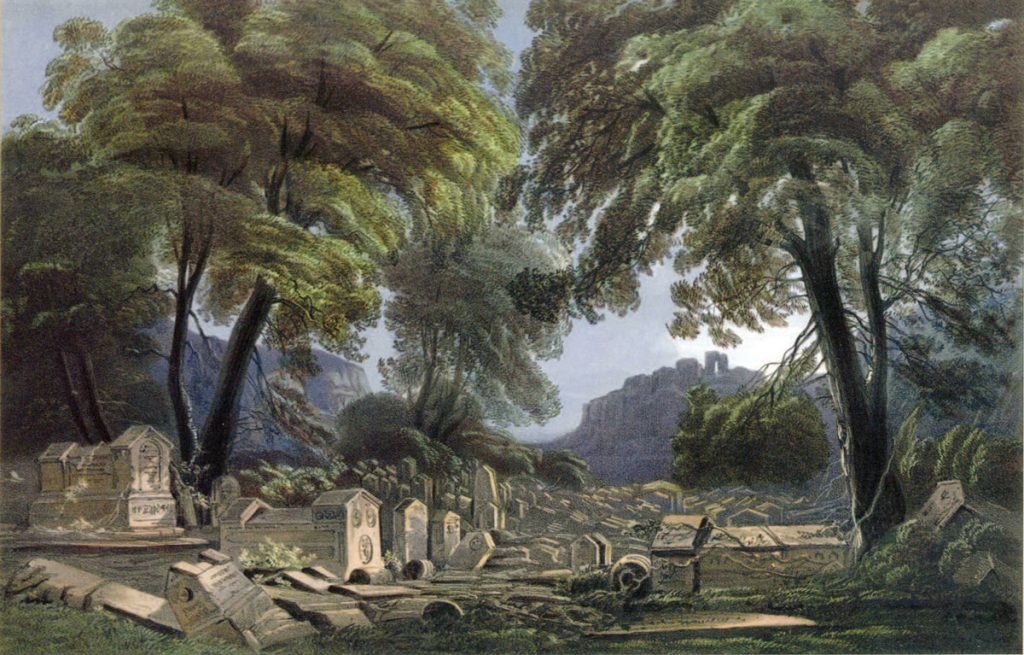

Jews and Karaites

Jews, as part of a growing diaspora in the Mediterranean basin, moved to Ukrainian lands during the first centuries of the Common Era. The first Jews in Ukraine were maritime merchants who settled in the coastal towns of the Black Sea, which they co-founded with Greek colonists. Jews traded in commodities from China, Persia, northern Africa, northern Europe, and, later, the Byzantine Empire. For several centuries, they were concentrated in Crimea and around what is today Kerch, Sevastopol (ancient Chersonesus), and the mountain-top settlement of Chufut-Kale near Bakhchysarai. Several matsevot (gravestones), ruins of synagogues, ritual baths, and other archaeological artifacts attest to their historic presence in the Crimean peninsula. These mostly Jewish tradesmen founded small yet vibrant traditional communities with a characteristic Judaic infrastructure centered in and around the synagogue, the study of the traditional (written and oral Torah — Ukr.: Pyatyknyzhzhya) texts, and Judaic religious rites based on rabbinic traditions. They later came to be known as the Krymchak, or Crimean Jews.

Crimea's Jewish communities functioned peacefully until the ninth century CE, when they were joined and at times threatened by groups of Karaite migrants. The Karaites were anti-rabbinic Jewish sectarians from Persia who passed through the Land of Israel on their way to southern Crimea. They settled in Theodosia (today Feodosiya), which was to become in subsequent centuries the most significant of all Black Sea ports. Several centuries later, after the Black Sea coastal areas of Crimea came under direct Ottoman rule (1475), the new authorities, following Islamic practice, tolerated both groups but designated them differently: the indigenous Krymchaks as "Jews with earlocks," and the Karaites who were disrespectful of rabbinic law as "Jews without earlocks."

Jews also settled in Ukrainian lands that were within the sphere of the Khazar Kaganate. As popular medieval legend has it, in the eighth century the pagan king of Khazaria, Bulan, arranged for a debate between the representatives of three major monotheistic religions. He found Judaism the most rational and convincing faith and, therefore, himself converted to Judaism. Eventually, Bulan brought rabbinic scholars to his court and Judaized the entire realm, thereby allegedly transforming the Khazar Kaganate into the only existing and prosperous medieval Jewish polity. Based on subsequent Arabic travelogues, the Bulan tale proved to be nothing but a later medieval legend known as "the choice of faith," something familiar to many peoples, including Ukrainians and Russians.

Indeed, there were groups of Jewish merchants living in Khazar lands, where they conducted missionary activity otherwise outlawed in Christian Europe. But even if some members of the ruling elite may have converted for a brief period to Judaism, the Khazar Kaganate was never a Judaic polity. This is attested by archaeological sources — from coins to pottery to graves — and by the fact that when the kaganate fell to the armies of Rus' the Khazar rulers were by religion Muslim. In short, the story of Khazaria's conversion to Judaism may be considered nothing more than a trope in a polemical discourse in medieval Hebrew literature originating in Muslim Spain.

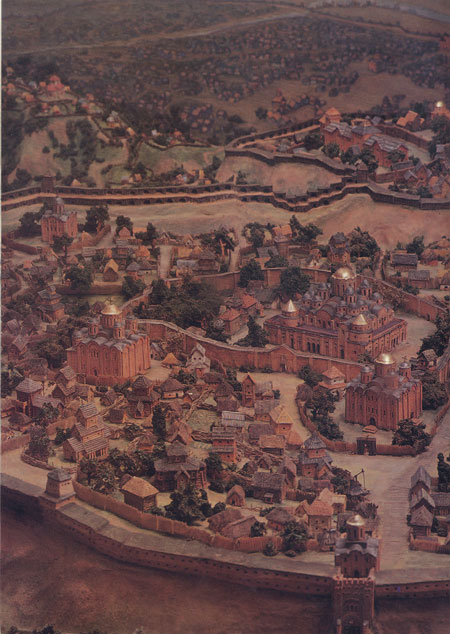

Kievan Rus'

All along the route from the Varangian (Baltic) Sea to the Byzantine Greeks, the Scandinavians set up trading posts, with Novgorod in present-day Russia and Kyiv in Ukraine eventually becoming the most prominent. The trading posts grew into towns and cities, which before the end of the ninth century evolved into a political entity known as Kievan Rus'. Initially governed by Scandinavian Varangians who were steadily being replaced by local East Slavic tribal leaders, Kievan Rus' extended its political influence over a wide expanse of territory stretching from the Gulf of Finland and the upper Volga River in the north to the point where the open steppe begins in the far south. In modern-day terms, this included western Russia, Belarus, and Ukraine as far south as the Ros River, beyond which was the open steppe.

Medieval Kievan Rus' and the steppe peoples

This far-flung realm was a typical European medieval political entity — a loose conglomerate of principalities headed by rulers linked by family ties, who traced their lineage to the founding dynasty named after the mid-ninth-century Scandinavian chieftain, Hroerkr/Riuryk. The Riurykide princes throughout the Rus' realm nominally paid homage to the family's senior member, the grand prince resident in Kyiv. The realm reached its apogee during the late-tenth and eleventh-century reigns of grand princes Volodymyr/Vladimir ("the Great," r. 980–1015) and Yaroslav I ("the Wise," r. 1019–1054). Kievan Rus' was dynastically integrated with the rest of medieval Europe, since the sons and daughters of its grand princes married into the ruling houses of Norway, France, Poland, and Hungary, among other countries. In terms of culture, the Kievan realm was closely linked to the Byzantine Empire, with which it maintained active economic ties and from which it received in the late tenth century Christianity according to the Eastern Byzantine rite. Eastern Orthodoxy became the official religion of all the Rus' principalities and ever since has remained the dominant religious culture in those lands regardless of which state rules them.

Most of modern-day Ukraine's territory was outside the realm of Kievan Rus', since the steppelands were initially controlled by the Khazars and later various Turkic nomadic pastoralists, while far southern Crimea and its Black Sea coastal region were controlled by the Byzantine Empire and its allies. In the 960s a dynamic Rus' grand prince (Svyatoslav) destroyed the Khazar Kaganate. Thereafter, the steppe became an unstable zone inhabited by warring nomadic Turkic tribal groups (Pechenegs, Polovtsians, etc.), who were in almost constant military conflict with Kievan Rus' for most of the rest of its history. The most destructive of these warriors from the east were the Mongols, who, with their vast armies comprised primarily of various Turkic tribal groups from Central Asia and known by the generic term Tatar, conquered many of the leading cities of Kievan Rus' between 1237 and 1241. The city of Kyiv itself fell to the Mongols at the end of 1240, and within the next few decades Kievan Rus' as a distinct political entity came to an end.

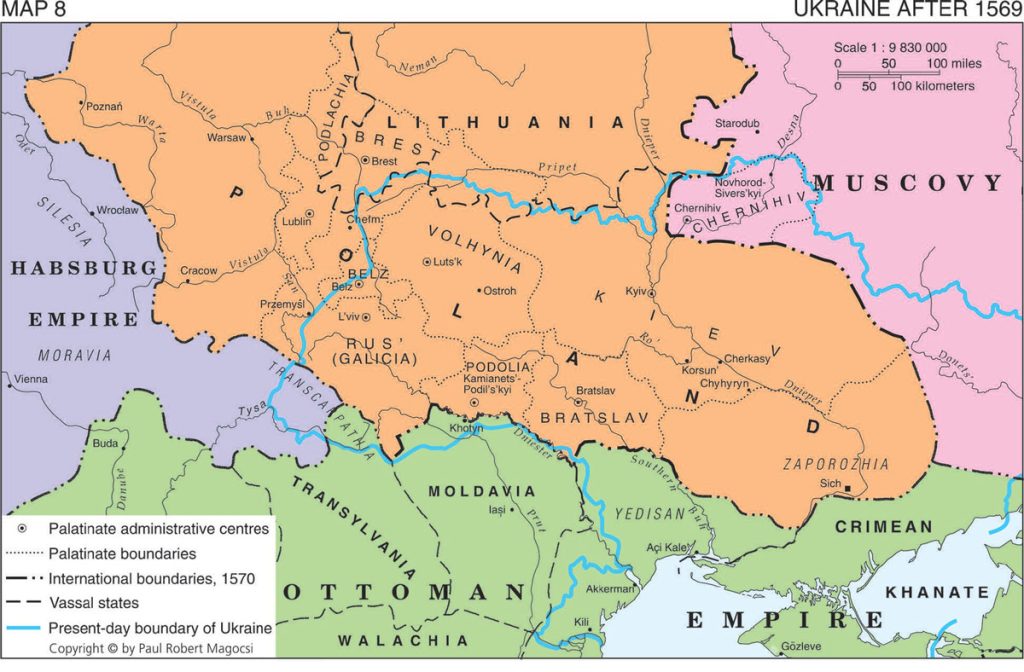

The independent principality and later kingdom of Galicia-Volhynia, with its capital of Lviv in far western Ukraine, carried on Rus' political and cultural traditions as an independent state until the mid-fourteenth century. Thereafter, the territory of modern-day Ukraine came under the control of three powers: (1) the Mongol-Tatar-ruled Golden Horde and its successor state, the Crimean Khanate; (2) the Grand Duchy of Lithuania; and (3) the Kingdom of Poland. Two other smaller areas remained under entirely different rule: Transcarpathia within Hungary; and Bukovina within Moldavia.

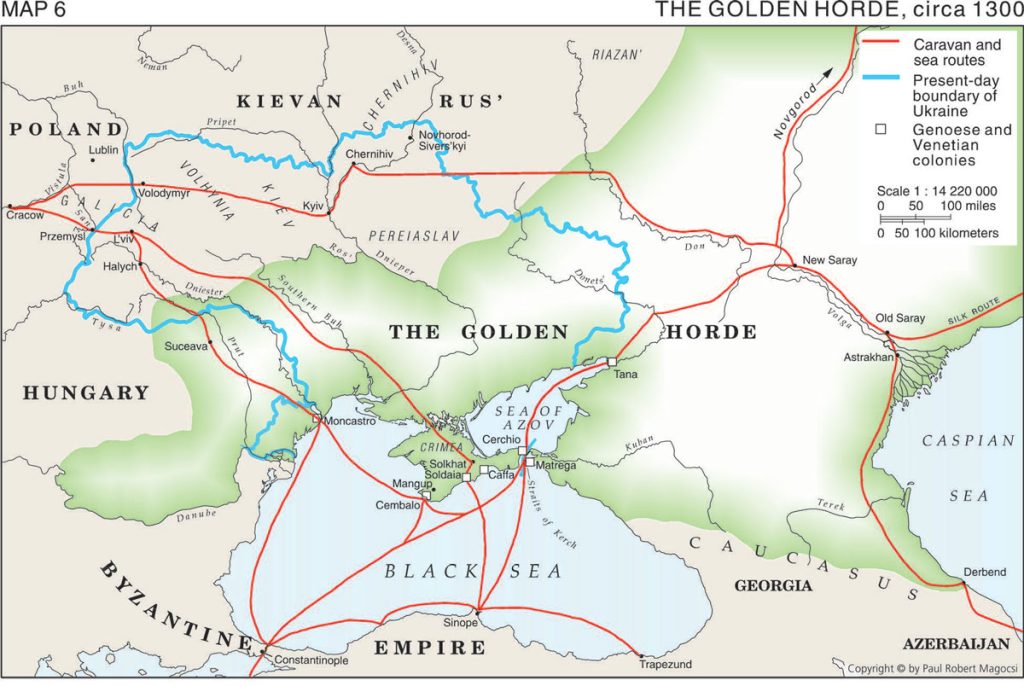

The Golden Horde was formed in the 1240s as the far western component (ulus) of the Mongol Empire. It was based, like the earlier Khazar Kaganate, on the lower Volga River, and it encompassed all of southern steppe Ukraine and Crimea as far west as the Carpathian Mountains. Also, like the Khazars before them, the Mongol-Tatar Golden Horde derived its wealth from the duties it levied on international trade along the famed Silk Route that ran from China through Central Asia and the Golden Horde before reaching the route's terminus in Crimea. The Mongols allowed trading companies from Genoa and Venice to set up bases in Crimea's Black Sea ports, in particular Italianate Caffa (modern-day Feodosiya), where they processed goods (spices, silks, slaves) that were sent on to the Mediterranean Islamic world and southern Europe.

Jews

Jews came to Kievan Rus' from central Europe, most likely from the lands of Bohemia and Moravia (present-day Czech Republic). These were the Yiddish-speaking Ashkenazim, whose ethnic denominator comes from the biblical word Ashkenaz, the name by which medieval Jews called the German lands. While we do not know when exactly these Jews arrived in Kievan Rus', it is certain that by the thirteenth century there were already small organized communities of Ashkenazim in what is today the central and northern Ukrainian towns of Ostroh, Volodymyr, and Chernihiv. The earliest Ashkenazic settlements are poorly documented and known only through oblique references found in rabbinic responsa (legal correspondence). There are references to Jews in the chronicles of Kievan Rus': for example, the story of monks in Kyiv's Monastery of the Caves (Pecherska Lavra) going at night to debate theological issues with local Jews. It turns out that such alleged encounters between Slavs and Jews were imaginary and simply reflected the polemical interests of later Orthodox religious writers.

Some Slavic written sources refer to groups of vagrant Jews who, already in the early tenth century, were living in the lower part of Kyiv, the Podil district. There they founded a community, although its exact location is unknown. The community's leaders included Jews from central Europe and Khazaria, as well as local Jews so well integrated into Kievan Rus' society that they adopted Slavic names. The complex origin of Kyiv's tenth-century Jewish community derives from a document found in the Cairo genizah (repository of discarded manuscripts) known as "the Kievan Letter." This is a document that communal leaders prepared for a Jew in Kyiv, who at the time had borrowed money but then was robbed and was looking for ways to repay his debt.

The Jews of Kievan Rus' were intellectually and religiously closely related to European (Ashkenazic) Jews. For example, a thirteenth-century Jew from Chernihiv went as far as London, where he taught a local Christian scholar how to write the Slavonic alphabet, read Slavonic letters, and even pronounce Slavic obscenities that are to this day recognizable. Another Jew from Volhynia went to study traditional Jewish texts with rabbinic scholars in Toledo, Spain; while a third went to a yeshivah (Talmudic academy) in the Germanic lands. Whenever Jews from eastern Europe needed to solve difficult religious and communal issues that they could not settle locally, they sent their legal inquiries to the disciples of the Hasidei Ashkenaz, pious and elitist Jews residing in the borderlands between Poland and Germany whom they considered their spiritual masters.

While Jews in Kievan Rus' knew the Slavic vernacular, Ashkenazic Jews brought with them the Yiddish language, pietistic customs, and magical beliefs popular in Germanic central Europe. Whatever the mixed origins of the early Jewish settlers in Kievan Rus', by the fifteenth century Yiddish-speaking newcomers had assimilated local Slavic-speaking Jews, so that Yiddish became the predominant language among Ukraine's and other eastern European Jews. It was the Yiddish-speaking Ashkenazic Jews who were to lead the religious, institutional, communal, educational, and cultural developments of the Jewish community in Ukraine for centuries to come.

Lithuanian-Polish-Crimean era

Not long after the Golden Horde came into being, a new power in the north arose, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. In the course of the fourteenth century, Lithuania expanded steadily and took under its rule most of the southern principalities of former Kievan Rus', which in Ukrainian lands included Volhynia, Chernihiv, Kiev, Pereyaslav, and Podolia. The other Rus' principality in this area, Galicia, after nearly half a century of military conflict with neighboring states (Hungary and Lithuania), was annexed to Poland in 1387.

The next important political change came during the second half of the fifteenth century. Discontented elements among the ruling strata of the Golden Horde broke away to create a new state structure called the Crimean Khanate. Although based in the Crimean peninsula, the new khanate also included steppelands in southern Ukraine between the Dnieper River and the Sea of Azov. This part of the steppe was eventually controlled by Tatar tribes known as the Nogay, who were only nominally under the authority of the Crimean Khanate. In 1475 the powerful and expanding Ottoman Empire invaded Crimea, took the coastal cities under its direct control, and effectively incorporated the Crimean Khanate into its political sphere as a semi-independent vassal state. It was not long before Crimea's economy came to be based to a significant degree on the slave trade. Expeditions of Crimean and Nogay Tatars set out several times a year to Lithuanian- and Polish-ruled Ukraine and Muscovite-ruled Russia, where they captured East Slavs who were sold to buyers in the Ottoman-controlled Crimea port of Kefe (former Caffa/Feodosiya). Between 1500 and 1664, an estimated one million people from Ukraine and southern Russia were captured and sold into Crimean and Ottoman slavery. One result of this massive demographic change was to transform much of Ukraine — especially the open steppe region south of the Ros River — into what came to be known as the uninhabited Wild Fields. In effect, Ukraine was what its very name means: a borderland (ukraina) or no-man's land between Poland and Lithuania to the north and the Crimean Khanate to the south.

Cossack phenomenon

The sixteenth century proved to be an important turning point during which three developments took place that were to have a lasting impact on Ukraine and all its inhabitants. By the very outset of the century, it had already become common practice for peasant farmers and others of a more adventurous bent to go on short expeditions into the no-man's land in order to exploit the seemingly boundless natural wealth in plant life and animals. Temporary visits eventually turned into permanent habitation, and to protect themselves from Nogay Tatar slave-raiders, the settlers quickly learned military skills. This phenomenon came to be known as the Cossack way of life. By the mid-1550s, the Cossacks set up their first permanent fortified camps, called the sich, on islands within the broad Dnieper River, just south of several impassable rapids (near the present-day city of Zaporizhzhya) in south-central Ukraine. Because their center was "beyond the rapids" (za porohamy), they came to be known as the Zaporozhian Cossacks.

The sich and surrounding steppe land on both banks of the Dnieper River attracted an ever increasing number of peasants and other elements not wanting to live under what they considered oppressive rule. The arriving refugees were mostly males of various ethnic and religious backgrounds — Poles, Lithuanians, Romanians, Tatars, Jews, among others — although the vast majority were East Slavic Rus' people, the ancestors of modern-day Ukrainians.

The second sixteenth-century development, although political in nature, had very significant socio-economic implications. Ever since the late fourteenth century, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania was moving gradually but ever so steadily closer to its neighbor to the west, Poland. The culmination of this process was reached at the Union of Lublin in 1569, when both parties formed a state called the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. Although Lithuania remained a distinct component of the joint commonwealth, in the very same year the entire southern part of the grand duchy was annexed to Poland. In effect, Ukrainian lands that had been in Lithuania — and this included, at least nominally, Cossack-inhabited Zaporozhia — were now administratively part of the Kingdom of Poland.

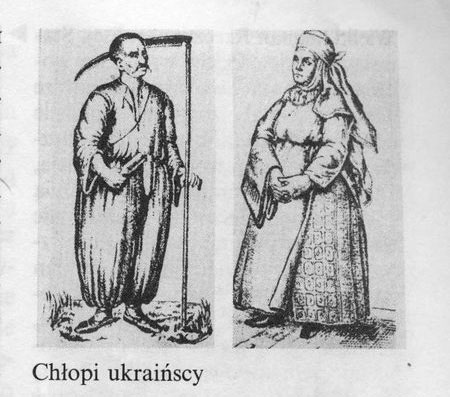

Socioeconomic and religious developments

Among the Polish laws introduced into Ukrainian-inhabited lands was a decree of 1573 attaching peasants to the manorial estates of their landlords. This meant that the vast majority of Ukraine's rural population became proprietary serfs owned by Polish landlords. Poland itself had by the sixteenth century become a major exporter of raw materials to western Europe, in particular lumber, hides, and valuable cash crops like wheat, shipped down the Buh and Vistula rivers to Poland's port of Danzig/Gdańsk on the Baltic Sea. As the demand for wheat in particular grew, Polish landlords developed estates farther and farther eastward into Ukraine on both sides of the Dnieper River. Proprietary serfs were brought in to work the land, and middlemen — mostly Jews but also German, Armenian, and Tatar migrants — were hired by the Polish landlords to manage their ever-growing manorial estates and subsidiary interests (mills, distilleries).

The third sixteenth-century development was cultural or, more precisely, religious in nature. In pre-modern times, most people identified themselves according to their religion, not their language or ethnicity. Many states, moreover, adopted an "official" religion, so that one could not be a full-fledged subject if one were not of the state religion. Of the states ruling Ukrainian territory in the sixteenth century, Poland and Lithuania were Roman Catholic, and the Crimean Khanate Muslim. Meanwhile, the majority of the population in the eastern lands of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth (Ukraine and Belarus) comprised Slavic Eastern-rite Orthodox Christians. They were the inheritors of a religious tradition that began with the official adoption of Christianity from the Byzantine Empire by Grand Prince Volodymyr/Vladimir of Kievan Rus' back in 988. But Kievan Rus' no longer existed, and in sixteenth-century Roman Catholic Poland-Lithuania the Orthodox Rus' (Ukrainians and Belarusans) were more often than not treated as second-class subjects.

In an effort to improve their status and at the same time to heal the theological rift between the Roman Catholic West and Orthodox East, clerical and secular Orthodox leaders in Poland-Lithuania considered the desirability of church union between the Orthodox and Roman Catholics in all countries. That ideal goal was never achieved, however. Instead, only a portion of the Orthodox in one country, Poland-Lithuania, accepted what came to be known as the Union of Brest (1596). The Uniates, as they came to be known, retained the Eastern rite but recognized the pope in Rome as the head of their church. The Orthodox who refused to accept the Union of Brest were branded as "schismatics", that is, those who were in schism, or separated from the universal Catholic Church. Instead, they remained under the ultimate authority of the ecumenical patriarch of Constantinople, who by then was an unwilling subject of the Ottoman Empire. To make matters worse, the Polish authorities outlawed the Orthodox and recognized the Uniates as the only acceptable form of what was henceforth the Eastern-rite Catholic Church.

The socio-economic disparity and the religious tensions between the Rus' population of Ukraine and Poland-Lithuania's ruling elite (not all of whom were necessarily Roman Catholic ethnic Poles) resulted in periodic revolts and uprisings during the first half of the seventeenth century. This was a time when the Cossacks (some in the service in Poland, others living beyond direct governmental control in Zaporozhia) came to see themselves and were considered by church leaders as defenders of the Orthodox faith of the Rus' people of Poland-Lithuania. Several Cossack leaders (hetmans) from the period like Petro Sahaidachnyi are remembered to this day as heroes for their exploits against the Ottoman Turks and Crimean Tatars and as defenders of liberty against Polish oppression. This image of the freedom-loving patriotic Cossack was later immortalized through the medium of literature in the short story Taras Bulba, by the nineteenth-century Russian-language Ukrainian author, Nikolai Gogol.

Jewish communities

Jews, like the ethnic Rus' inhabitants in Ukrainian lands, found themselves after the dissolution of Kievan Rus' living under the rule of three states: Lithuania, Poland, and the Crimean Khanate. The Jews of Crimea, as everywhere else in the medieval Muslim world, enjoyed the status of dhimmis. This meant that they were a tolerated monotheistic minority whose members were allowed to practice freely their religion, to engage in commerce, and to serve as doctors and translators at the courts of the Muslim rulers in exchange for their acknowledgment of the primordial, triumphant, and higher status of Islam. They could not, however, ride horses, bear arms, or emphasize their visibility, importance, and prestige, but rather had to keep a low profile. Jewish and Karaite communities in Crimea prospered in high medieval and early modern times in towns such as Caffa (Feodosiya), Gözleve (Yevpatoriya), and Chufut-Kale (near Bakhchysarai).

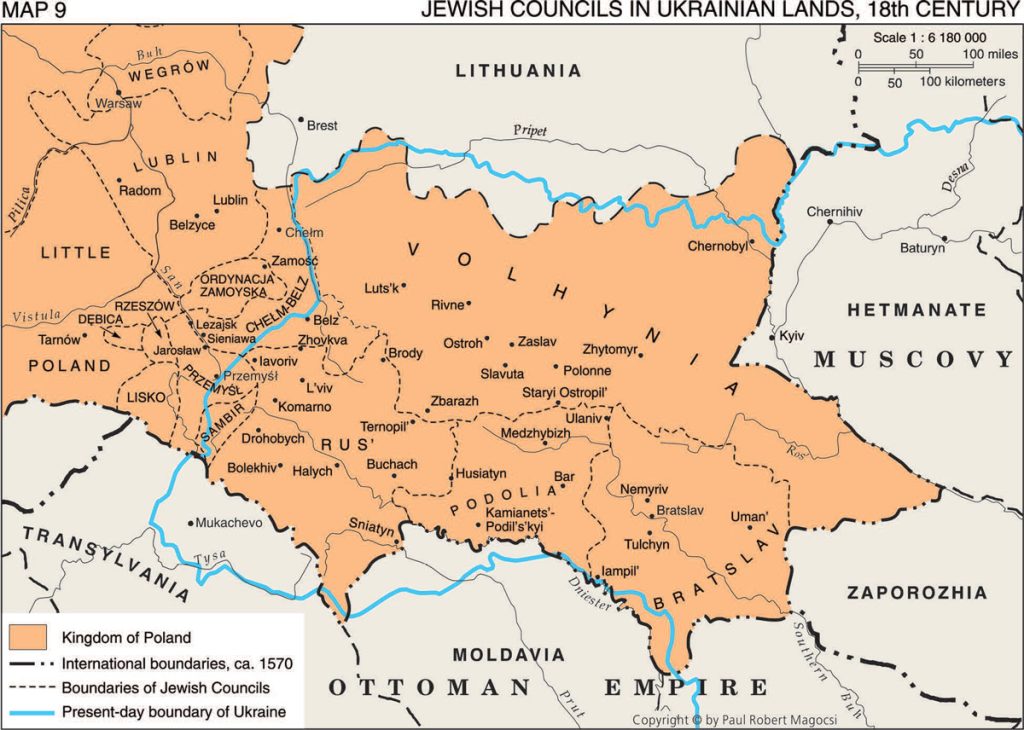

Jews living in the Lithuanian and Polish-ruled lands of Ukraine (Volhynia, Galicia, and Podolia) enjoyed the legal status of servi camerae, servants of the royal chamber. As such, they were considered free subjects, although legally they were the property of the monarch. While they entirely depended upon the whim of the monarch, they also could rely on his power, since any attack against a Jew or Jewish property was considered an attack against the king or his property. Jewish life and settlement under Polish rule were governed by a complex system of privilegias (concessions) which defined the group's communal, religious, and economic activities. The first privileges granted to eastern Europe's Jews bear the signatures of Poland's rulers, including Bolesław ("the Pious," r. 1239–1279) and Kazimierz/Casimir III ("the Great," r. 1333–1370). Reconfirmed or reinforced by subsequent rulers, the Polish privilegia replicated similar documents granted to Jews in Bohemia and elsewhere in central Europe. The existence of these documents and the fact that the group's dominant language was Yiddish attests to the Ashkenazic origin of Poland's and Lithuania's Jews. They were allowed to engage in moneylending, currency exchange, and tax collecting, and they were given full religious freedom. The Polish model for Jewish communal life spread eastward into Ukrainian lands, which at the time were in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. Therefore, by the fifteenth century, there were communities with Jewish educational, legal, and religious institutions in Lviv, Lutsk, Ostroh, Volodymyr, and Kyiv.

The Jewish migration eastward intensified in the sixteenth century following the long-lasting rapprochement of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, which after 1569 became one polity, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. This was also a time when the Counter-Reformation reached Poland-Lithuania and when the heretofore relatively tolerant policies of Poland's Jagiellonian dynasty began to change. Under the pressure of competitive urban merchants and artisans, in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, several major Polish cities under royal control received what for them was a privilege, namely a decree, De non tolerand Judaeis, which forbade Jews to settle or own real estate in urban areas. This restriction, which was religious in its language and economic in its underpinnings, eventually pushed Jews beyond the city walls and gave them good reason to move elsewhere should conditions be more attractive. More attractive conditions were indeed made available by Poland's nobility (szlachta), in particular its most wealthy upper stratum, the magnates.

As payment for their services to the rapidly expanding commonwealth, Poland's magnates were granted vast, largely underpopulated territories especially in Ukraine, which as a result of the 1569 Union of Lublin was annexed from Lithuania to Poland. Since the magnates were more concerned with economic prosperity than with religious conformity, they invited Jews to take up managerial posts in their ever-expanding manorial landed estates (latifundia) and to reside in the dozens of noble-owned surrounding towns, among them Tulchyn, Polonne, Korets, and Sharhorod.

The magnates also obtained from the Polish crown the right to establish trade and annual fairs in their towns. There they granted Jews exclusive economic privileges as merchants and as leaseholders of various economic activities, including mills and customs, tax farming, liquor production, and tavern keeping. By the mid-seventeenth century, more than forty magnate-owned towns became walled fortresses. Uman in Bratslav province, for example, had a magnate's palace, a small but permanent Polish garrison, and a complex urban infrastructure including trade, crafts, and guilds staffed predominantly by Jews. Uman and numerous other Ukrainian towns in Volhynia, Podolia, Bratslav, and Kiev provinces came into being as a result of the latifundia system established by the Polish magnates and mostly operated by Jews.

As in other parts of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, the Jews in Ukrainian lands enjoyed a high level of legal and communal autonomy. The Council of Four Lands (Heb.: Vaad arba aratsot), which functioned from the early sixteenth century to 1764, was an umbrella organization uniting all Jewish communities. Acting somewhat like the commonwealth's national parliament (Sejm), the Council assumed responsibility (including collection of taxes) for Jewish interests before the Polish crown, and it issued regulations of a religious and socio-cultural character that were binding for all Jewish congregations throughout Poland-Lithuania. Each Jewish community had its own kahal, a communal institution run by the local financial and commercial oligarchy. The kahal controlled the tax burden and distribution of charitable funds, supervised religious observance, reinforced cultural boundaries, hired and dismissed rabbinic leaders, and supported traditional philanthropic and educational confraternities.

As a result of the close economic association of the Jews with Poland's magnates — not to mention traditional attitudes among Christians throughout Europe at the time — the majority and predominantly rural Orthodox Rus' population of Ukraine viewed Jews as people of a different creed (Judaism), different economic status (functionaries of the magnates), different social entity (urban), and different language (Yiddish). They were, therefore, considered alien. Such a perception and other social tensions were the cause of frequent rebellions during which Jews were at times singled out and killed. Nevertheless, the Rus’-Ukrainian population and the Jews of Ukraine lived in a symbiotic relationship for over four hundred years of Polish-Lithuanian rule that was based on mutually beneficial economic if not social co-existence of the two subjugated groups.

Cossack- and Crimean-ruled Ukraine

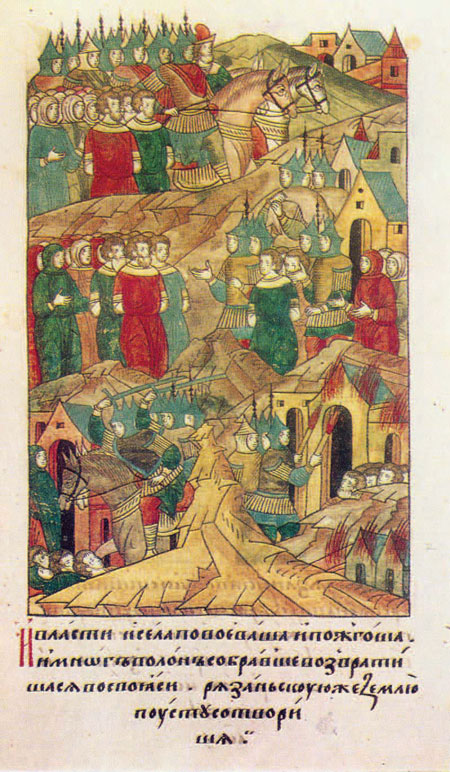

Khmelnytskyi uprising

The ongoing tensions and social discontent in the eastern borderlands of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth culminated in 1648 with the outbreak of a major uprising led by the Cossack hetman Bohdan Khmelnytskyi. In contrast to previous relatively short-lived revolts, Khmelnytskyi managed to unite the interests of the Cossacks of Zaporozhia, the Cossacks in the service of the Polish Kingdom, and the socially elite nobles of Orthodox Rus' origin, all of whom joined in what became a wide-ranging military conflict with Poland. The Cossack leader also reached an agreement with Crimea's khan, promising him a share of the campaign booty (including captives to become slaves) in return for military support against Poland.

The Cossack-Tatar alliance was indeed successful, and in the wake of several military victories by Khmelnytskyi's forces against the commonwealth's armies, widespread peasant uprisings broke out throughout Ukraine. Some occurred spontaneously, others were led by Cossack chieftains (otamany) nominally linked to Khmelnytskyi. What united these diverse elements was deep discontent with the inequalities of Polish rule and a particular hatred for the main representatives of that rule: the Polish nobility (szlachta), the Roman Catholic and Uniate clergy, and the administrators (mostly Jews) of the noble-owned manorial estates on which the enser-fed peasantry toiled.

Cossack state between Poland and Muscovy

In August 1649 Hetman Khmelnytskyi managed to reach an agreement whereby Poland recognized Cossack rule in three of the commonwealth's eastern provinces (the palatinates of Kiev, Bratslav, and Chernihiv). This became the core of a semi-independent Cossack state later known as the Hetmanate. In an effort to enhance the status of the Cossack Hetmanate, Khmelnytskyi sought alliances with neighboring Moldavia, Transylvania, Muscovy, the Crimean Khanate, and the Ottoman Empire. Eventually, he and the Zaporozhian Cossacks pledged an oath of allegiance to the tsar of Muscovy at what became known as the Agreement of Pereyaslav of 1654. From that moment the Muscovite tsar added to his royal title the land of Malaia Rus' (Ukraine).

Not unexpectedly, the 1654 alliance — some would say subordination — of the Polish subject Khmelnytskyi to the tsar resulted in war between Muscovy and Poland-Lithuania. For the next several decades, Ukraine was ravaged by invasions of foreign troops and clashes among Cossacks allied with one or more of the competing invaders. This period of ruin (Ruina) gradually ended after the agreements reached between Poland and Muscovy in 1667 and 1686. Thereafter, the northern half of Ukraine was divided more or less along the Dnieper River. Lands to the west of the Dnieper, on the so-called Right Bank, remained within Poland-Lithuania; lands to the east, the so-called Left Bank — Cossack Hetmanate (including the city of Kyiv on the Dnieper's Right Bank) and Zaporozhia on both banks — were recognized as part of Muscovy. Meanwhile, all of southern Ukraine remained within the Crimean Khanate and its ultimate sovereign, the Ottoman Empire. The Ottomans, at the height of their expansionist phase, also annexed a large portion of Right Bank Ukraine from Poland, which they held on to until 1699.

In this divisive atmosphere, Cossack leaders, whether those in Zaporozhia, in the Polish-controlled Right Bank, or the Muscovite Left Bank, tried to maintain some form of political autonomy for their given region. The most successful in this regard was Ivan Mazepa, from 1687 the hetman in the Muscovite Left Bank. With the backing of Tsar Peter I ("the Great," r. 1682–1725), Mazepa was able to transform the Cossack Hetmanate into a viable self-governing entity within the framework of the Tsardom of Muscovy. After the outbreak of the Great Northern War in 1700, however, Cossack Ukraine was drawn into Muscovy's monumental and exhaustive military struggle with Sweden for domination of the Baltic region, including Poland-Lithuania. Unexpectedly, in late 1708, Mazepa and a small number of Cossacks defected to the Swedes. They did so, most likely, seeking to enhance the independence of Cossack Ukraine from the Muscovite tsar. But this act, and Peter's resounding Muscovite victory over Sweden at the Battle of Poltava in July 1709, were to have disastrous consequences for the Cossack state in Left Bank Ukraine.

Jewish-Cossack relations

Developments in Jewish communal life during the seventeenth century occurred in response to the ongoing social and ethno-religious clashes between the Orthodox Rus' population and the commonwealth's ruling Polish nobility. Undoubtedly, the most important of these clashes was the Cossack uprising led by Bohdan Khmelnytskyi, which ever since has been recorded in Jewish cultural memory as the gzeyres takh vetat — the Catastrophe of 1648–1649. More than any other event, this war between the Zaporozhian Cossacks and the Polish szlachta cast a heavy blow on eastern Europe's Jewish communities, although its impact was not the total destruction of Jewish life that the contemporary Jewish chronicler Natan Note Hannover portrayed in his widely read book, Abyss of Despair (Yeven metsulah, 1653).

Claiming to defend their own privileges and Eastern Orthodoxy, the Cossacks sought the destruction of their oppressors, in particular the Polish nobility and the Roman and Uniate Catholic churches. At the same time, urban Jews suffered enormously whenever major towns were attacked and ruined by the rebellious troops. Most (but not all) Jews saw the Cossacks as villains, in contrast to the Poles, who were regarded as representatives of civilized society and legitimate power. Hence, they armed themselves to defend the towns alongside Polish forces ranged against the Cossacks.

Some Jews had a more ambivalent attitude toward the Cossacks and perhaps even sympathy for the oppressed rebels. This seems to be confirmed by Jewish scholars such as Abram Harkavy, who has uncovered cases of Jews joining the Cossacks, and it explains why some Ukrainian writers such as Yurii Kosach make references in their works to brave Jews. According to chronicles from that time, the Poles besieged in walled towns traded their Jews for an armistice with the Cossacks, even though often the Cossacks disposed of the szlachta the moment there were no more Jews around to help the Polish defense of urban areas. Such was the rather complex environment in which several dozen Jewish communities, including those of Tulchyn, Nemyriv, and Polonne, were decimated. Of some 80,000 Jews residing at the time in the Ukrainian lands of eastern Poland, an estimated 14,000 to 18,000 perished and about 1,000 converted to Orthodoxy under duress. Several thousand more became refugees, including about a thousand taken prisoner by Crimean Tatar troops (as recompense for their military support of the Cossacks) to be sold in the slave markets of Crimea and Istanbul.

The impact of these upheavals on the cultural and religious imagination of eastern Europe's Jews was long lasting. It is understandable that the Jewish chroniclers, evoking the biblical Lamentation of Jeremiah, exaggerated the devastation. Ever since, Jews have marked the Catastrophe of 1648–1649 with a public fast on the 20 of Sivan (May or June), during which they recite liturgical dirges commemorating the victims of the massacres. Popular memory portrayed the destroyed communities as those of pious martyrs who perished committing acts of kiddush ha-shem, the sanctification of the divine name. Individual victims of the 1648 Catastrophe, such as the top expert in Kabbalah Jewish mysticism, Shimshon ben Pesah of Ostropolye (Ostropil in Volhynia), acquired fame comparable to that of the great rabbinic scholars massacred by the Romans in the aftermath of the Bar Kochba revolt in the second century CE. Jewish popular memory subsequently associated the Cossacks with merciless barbarians and perpetrators of anti-Jewish violence, while Ukrainian heroic songs (dumy) from the eighteenth century portrayed the Jews as bloodsucking Polish lackeys ingratiating themselves with the oppressive landlords.

Despite the subsequent rhetoric on both sides, the devastating impact of the 1648–1649 Catastrophe proved to be temporary. As early as the mid-1650s, many Jewish refugees had returned and rebuilt their homesteads and businesses, reclaimed their looted property (if they could identify it), restored the synagogues, and even paid the ransoms demanded for family members held in Crimean bondage. So successful were the reconstruction efforts that by 1655 the Council of Four Lands stopped extending social relief to the damaged communities, claiming that they had managed to revive and re-establish themselves. As the result of several agreements between the Cossacks and Poles, the Jews were allowed to reside in Right-Bank Ukraine (west of the Dnieper River). They were not allowed to reside in Left-Bank Ukraine (east of the Dnieper River), which included the Cossack Hetmanate state and other lands under Muscovite rule.

Muscovite-, Polish-, and Crimean-ruled Ukraine

The eighteenth century witnessed a major realignment between the states that ruled Ukrainian territory as well as a change in the political status of the Cossack state. Heralding this development was the formal transformation in 1721 of the Tsardom of Muscovy into the Russian Empire. Thereafter, the power and territorial extent of tsarist Russia grew at the expense of Poland-Lithuania, the Crimean Khanate, and the Ottoman Empire.

Cossack autonomy and division of Ukraine

In the Russian-ruled Left Bank Ukraine, its three regions — the Hetmanate, Zaporozhia, and Sloboda Ukraine — each lost its self-governing status until all were integrated fully into the administrative structure of the rest of the empire. The process was gradual, beginning first with Sloboda Ukraine in the 1760s, continuing with Zaporozhia in the 1770s, and culminating with the abolition of the Hetmanate in the 1780s. These developments took place during the long reign of Empress Catherine II ("the Great," r. 1762–1796), whose policies also had a profound impact on Ukraine's social structure. Persons of noble status from the era of Polish rule as well as a portion of the Cossack elite were recognized as members of the Russian nobility; the remaining Cossacks were basically removed from Ukraine and resettled to peripheral areas of the empire; and the peasants on manorial estates lost their freedom of movement and became proprietary serfs owned by their aristocratic landlords.

In Polish-ruled Right Bank Ukraine, the eighteenth century began with Poland-Lithuania's reacquisition of lands in south-central Ukraine that it had lost to the Ottoman Empire: the provinces (palatinates) of Bratslav, Podolia, and southern Kiev. There the Polish socio-economic system was restored with the return of nobles, whose extensive manorial estates worked by proprietary peasant serfs (mostly Ukrainians) were again managed by Jewish middlemen. The returning Polish nobles not only built on their lands monumental-sized manorial palaces, they also owned several towns and had their own military units (made up of Cossack-like formations) to protect their property from foreign invasion and internal revolts.

Haidamak revolts and partitions of Poland

Social instability, not uncommon among peasants, Cossacks, and townspeople who were discontent with the inequalities of Polish rule, did indeed result in armed revolt. This might take the form of small-scale brigandage carried out by opryshky (Robin Hood-like bandits) in the mountainous areas of far western Galicia, or large-scale uprisings against the manorial estates in Right Bank Ukraine. The latter were often led by Cossacks who, together with their peasant followers, were known as haidamaks. The greatest — and last — of the haidamak revolts occurred in 1768. Motivated by both Orthodox religious as well as social discontent, it spread throughout the southern Kiev and Bratslav palatinates and brought in its wake widespread destruction of several Polish manorial estates before being crushed by outside intervention, specifically Russian armies sent by Empress Catherine II. It was the 1768 massacre of 2,000 Jews (and at least as many Poles) by Cossack-led haidamaks in the town of Uman that has ever since remained embedded in the collective memory of Hasidic Jews. This was largely because the influential Rabbi Nachman of Bratslav later chose to reside and be buried in Uman in order to attract his followers to pray for the souls of the victims.

The presence of Russian troops in Poland-Lithuania was indicative of how, by the second half of the eighteenth century, the commonwealth had become so weak that it was easy prey to the expansionist desires of its more powerful neighbors. Between 1772 and 1795, Russia, in cooperation with Prussia and Austria, carried out three territorial partitions as a result of which Poland-Lithuania was wiped off the map of Europe. The Russian Empire acquired the lion's share of territory, the equivalent of what today are the countries of Latvia, Lithuania, and Belarus along with central Ukraine west of the Dnieper River. In cooperation with Russia and Prussia, the other power that acquired Ukrainian-inhabited territory from Poland was the Habsburg-ruled Austrian Empire. At the First Partition in 1772 it acquired the old Polish palatinate of Galicia/Red Rus'. Since the Habsburgs were kings of Hungary, Transcarpathia was already part of their realm; two years later, in 1774, Austria annexed from the Ottoman Empire the Carpathian mountainous region known as Bukovina.

While Poland-Lithuania was in decline, the Russian Empire could turn its full attention to its longtime rival to the south, the Ottoman Empire. Under Catherine II, the Ottoman vassal state, the Crimean Khanate, was annexed to the Russian Empire in 1783, as were about the same time other Ottoman territories along the northern shores of the Black Sea. Hence, by the last decade of the eighteenth century, virtually all territory within the present-day boundaries of Ukraine was under the rule of only two states: the Russian Empire and the Austrian Empire.

Jewish community and socio-cultural life

During the eighteenth century, Jews continued to play an increasingly important role in the economic life of Polish-Lithuanian-ruled Ukrainian lands. They assumed responsibility for the revitalization of the noble-owned private towns, principally in the Bratslav, Podolia, and Volhynia palatinates as well as farther west in Galicia. In all these towns, later known in Yiddish as the shtetlakh, Jews developed and dominated marketplace commerce, local arts and crafts, alcohol production, the sale and transport of wood, and international trade including grain. Although the Jews and Polish magnates formed a kind of "marriage of convenience," the nobles nonetheless exploited their Jews through an exorbitant taxation system that became particularly burdensome by the end of the eighteenth century. The magnates taxed or leased whatever they could to the Jews in exchange for cash, including customs offices, marketplace weights and measures, fishponds, certain crafts, and even rabbinic posts (more on that in Chapter 3).

The revitalization of the economy also intensified contacts between Jews and non-Jews, and this led to the blurring of cultural and even religious boundaries between people of different religious beliefs. It was not long before groups of religious enthusiasts emerged among the Jews in Ukraine parallel to the rise of religious reformers in other parts of Europe, such as the Moravian Brethren, Puritans, and Quakers.

During the last decades of the seventeenth century, a Jewish sectarian movement known as Sabbatianism made its appearance in eastern Europe. The Sabbatians believed that the long-awaited messiah had arrived in the person of Shabetai Tsevi, a Jewish native of the Ottoman Empire and eventual convert (1666) to Islam. Despite his apostasy and the consequent end of Sabbatianism as a mass movement, some followers (excommunicated elsewhere in Europe) persisted in their belief in him as the messiah. Among them were several hundred living in and around the Galician town of Zhovkva, where they remained until emigrating to the Land of Israel in 1704.

Although Sabbatianism disappeared from Ukraine's Jewish religious scene, the very presence of believers in pseudo- or false messiahs frightened the Jewish elites and helped to trigger the rapid spread of Kabbalah, a form of Judaic mysticism. Elitist Kabbalists gathered in a sort of a club/study group called a kloyz, a prayer house usually separate from the rest of the community where they studied mystical sources and indulged in certain mystically inspired prayers. Such elitist prayer houses dotted the territory of Ukraine, the most important among them in Kuty (Bukovina) and Brody (Galicia).

Toward the middle of the eighteenth century, yet another sect of religious enthusiasts led by Jacob Frank emerged in Podolia. Although small in number, the Frankists, as they were known, deviated radically from traditional Judaism and were viewed as a threat to Jewish religious authorities. Members of the group drew their ideas not only from the earlier sectarian Sabbatians but also from the ideology of the Moravian Brethren, one of the contemporary trends among Christian religious reformers. Frank, who saw himself as a reincarnation of the seventeenth-century pseudo-messiah Shabetai Tsevi, preached a fusion form of Judeo-Christianity and even encouraged his followers to seek salvation through orgiastic promiscuity. The Frankists boldly challenged the authority of the community's rabbis and denied the Talmud. In an effort to justify their beliefs and attract new followers, they arranged in 1757 for a public debate in Kamyanets-Podilskyi between themselves and Jewish rabbinic leaders. Soon after, however, the few remaining Frankists converted to Catholicism.

Alarmed by fusion forms of Judaism such as Frankism, which threatened to split Jewish communities, rabbinic leaders became highly cautious of any religious innovations. Therefore, it is not surprising that they did everything possible to nip in the bud any emerging heretical movements. The newest of these movements — innovative and therefore suspected of heresy — arose in Podolia during the 1760s and 1770s among informal groups of religious enthusiasts and followers of Yisrael ben Eliezer, better known as the Baal Shem Tov. Calling themselves Hasidim ("the pious ones"), they began popularizing the otherwise esoteric knowledge of Kabbalah among the masses. Despite the concerns of rabbinic leaders, the Hasidim made it clear that they were more concerned with emphasizing the spiritual life of the Jewish community, the revitalization of Jewish communal institutions, and the infusion of a sense of healing into traditional rituals than with introducing any radical change in Judaic tradition.

Nevertheless, until the end of eighteenth century, bans of excommunication were continually issued against the Hasidim by the mitnagdim (Yid.: misnagdim; literally, opponents of the Hasidic movement), who were predominantly Lithuanian Jews or Litvaks. Such opposition proved to be in vain, because Hasidism managed to capture the hearts and minds of Ukraine's Jews, moving from the periphery to a central position in the Jewish communities of Podolia, Volhynia, Kiev province, and Galicia. It was not long before Hasidism came to dominate the Jewish communities in what are today Belarus, Poland, and Romania.

In a word, Jewish communal life in the eighteenth century was entirely reconstituted. During the last partition period in the 1790s, the Polish authorities undertook several steps toward reforming the Jewish communities along the lines of the European Enlightenment, even discussing measures for Jewish reform in the commonwealth's parliament. But as Poland-Lithuania increasingly weakened and then disappeared entirely in 1795 as a distinct state, any reform proposals had to await the new governing administrations of Austria and Russia.

Click here for a pdf of the entire book.