Chapter 2.2: "Jews and Ukrainians: A Millennium of Co-Existence"

Jews and Ukrainians: A Millennium of Co-Existence is an award-winning book that explores the relationship between two of Ukraine’s most historically significant peoples over the centuries.

In its second edition, the book tells the story of Ukrainians and Jews in twelve thematic chapters. Among the themes discussed are geography, history, economic life, traditional culture, religion, language and publications, literature and theater, architecture and art, music, the diaspora, and contemporary Ukraine before Russia’s criminal invasion of the country in 2022.

The book addresses many of the distorted stereotypes, misperceptions, and biases that Ukrainians and Jews have had of each other and sheds new light on highly controversial moments of Ukrainian-Jewish relations. It argues that the historical experience in Ukraine not only divided ethnic Ukrainians and Jews but also brought them together.

The narrative is enhanced by 335 full-color illustrations, 29 maps, and several text inserts that explain specific phenomena or address controversial issues.

The volume is co-authored by Paul Robert Magocsi, Chair of Ukrainian Studies at the University of Toronto, and Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern, Crown Family Professor of Jewish Studies and Professor of History at Northwestern University. The Ukrainian Jewish Encounter sponsored the publication with the support of the Government of Canada.

In keeping with a long literary tradition, UJE will serialize Jews and Ukrainians: A Millennium of Co-Existence over the next several months. Each week, we will present a segment from the book, hoping that readers will learn more about the fascinating land of Ukraine and how ethnic Ukrainians co-existed with their Jewish neighbors. We believe this knowledge will help counter false narratives about Ukraine, fueled by Russian propaganda, that are still too prevalent globally today.

Chapter 2.2

The Historical Past

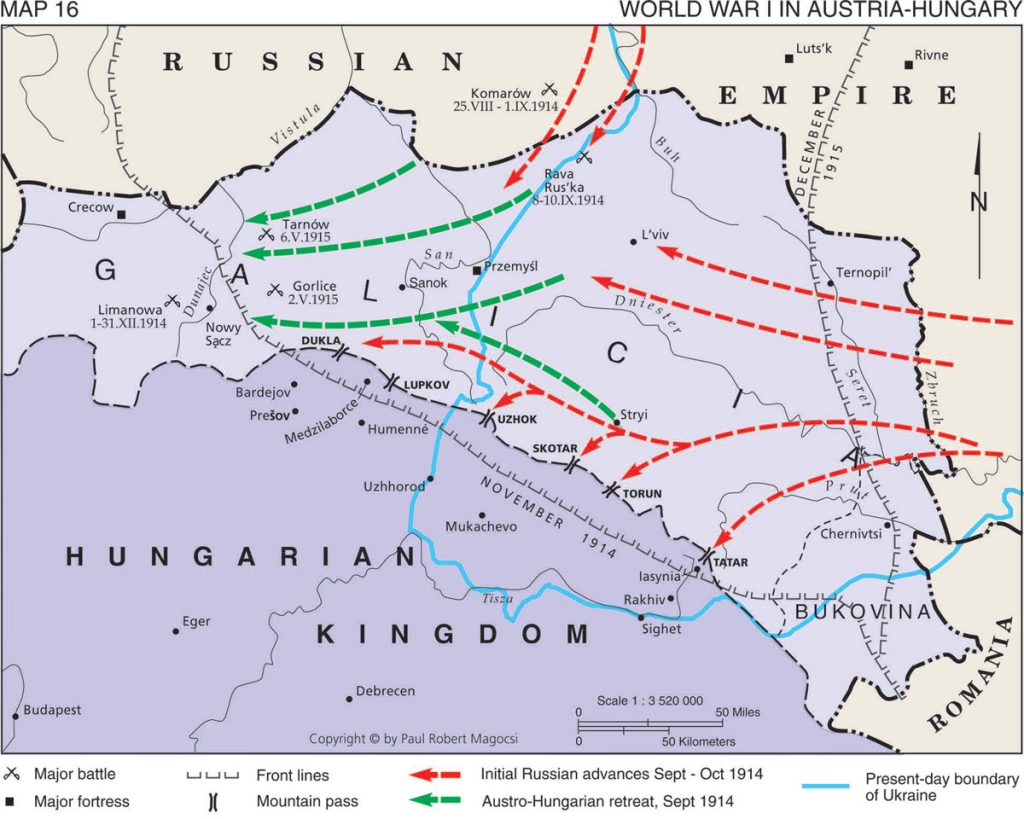

Russian- and Austro-Hungarian-ruled Ukraine

Ukrainian lands in the Russian Empire

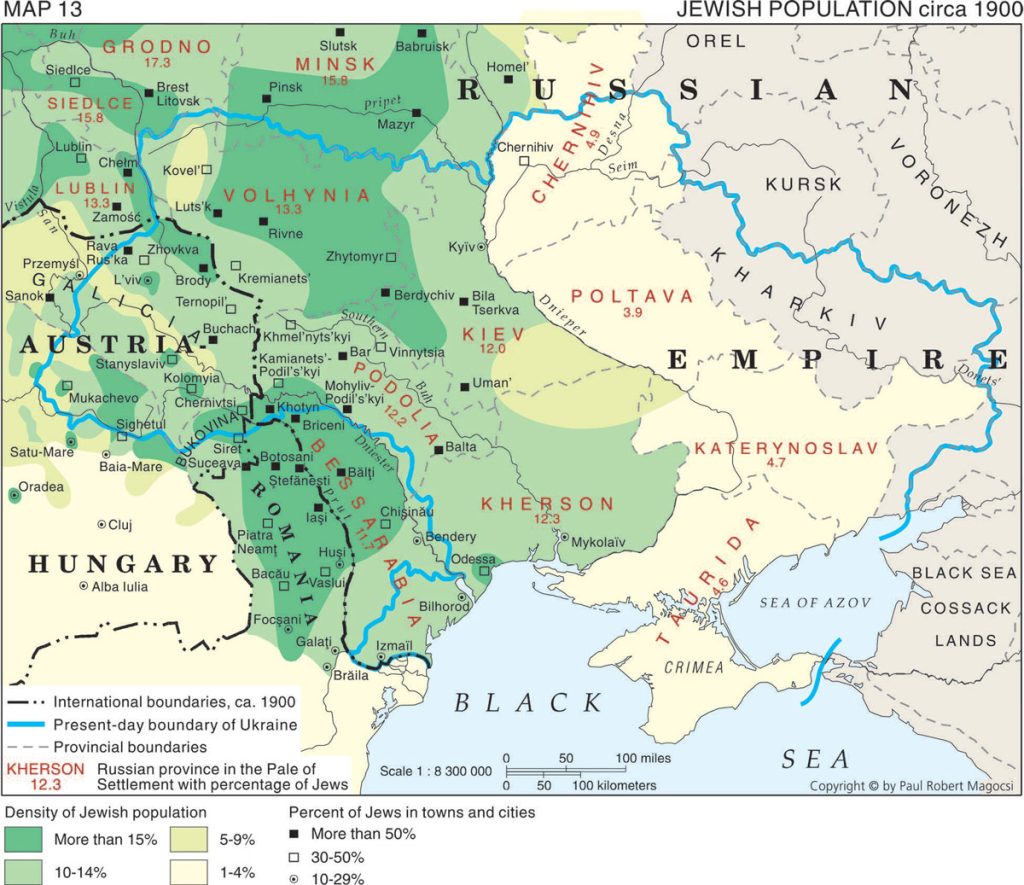

During the "long" or "historic" nineteenth century, which lasted from the 1780s to the outbreak of World War I in 1914, developments on Ukrainian lands differed significantly depending on whether they were under the rule of the Russian Empire or the Austrian Empire. The Russian Empire, which controlled about 85 percent of the territory and population within the boundaries of present-day Ukraine, was an autocratic state headed by a tsar resident in St Petersburg. Ukrainian territory, like the rest of the empire, was divided into nine provinces — Volhynia, Podolia, Kiev, Chernihiv, Poltava, Kharkiv, Katerynoslav, Kherson, Taurida, and small parts of Bessarabia — each of which was headed by a governor appointed by, and solely responsible to, the tsar.

The vast majority of the population comprised peasants, who lived and worked on lands owned by the state or as proprietary serfs on large private estates owned by landlords belonging to the noble social stratum (dvorianstvo). The nobility represented the most important social stratum in society; not only did they control socioeconomic developments, they also elected government officials in the local administration. Despite a period of reforms that took place in the 1860s and that provided for the emancipation of proprietary serfs from legal subordination to their landlords, the nobility continued its role as the dominant social stratum in Russia's imperial governmental and social system.

The long nineteenth century also witnessed three other phenomena: large-scale demographic growth; the opening up of large tracts of new agricultural lands, especially in steppe Ukraine; and the beginnings of industrialization, particularly in the Donbas region of eastern Ukraine. In Ukraine's Right Bank (the Pale), economic development was linked to agriculture, notably the export of wheat and sugar-beet refining, while in the Donbas the exploitation of local coal mines made possible metallurgical and related heavy industries. Most of the capital for these new enterprises came from western European investors, while the labor force, often subjected to very poor working conditions, was made up primarily of in-migrants from the Russian north. Together with industrialization was a three to four-fold growth in the population of cities, the largest of which (ranging in size from 100,000 to 700,000 inhabitants) were, by 1914, Odessa, Kyiv, Kharkiv, Katerynoslav (today Dnipropetrovsk), and Mykolayiv.

The demographic growth was due to a rise in natural fertility rates as well as the in-migration of settlers from other parts of the Russian Empire and immigration from abroad. Among the in-migrants were Russians, who were especially widespread in industrial eastern Ukraine and Crimea, while immigrants from abroad included Czechs, who went to Volhynia, and Germans, Bulgarians, Mennonites, and Greeks, who settled in the steppelands of south-central Ukraine and the lowlands north of the Black Sea and the Sea of Azov. Whereas ethnic Ukrainians (17 million in 1897) continued to make up the majority of the population in Russian-ruled Ukraine, nearly 30 percent of the inhabitants comprised other peoples, of which Russians (nearly 3 million), Jews (2 million), Germans (500,000), and Poles (400,000) were the most numerous.

Jews in the Pale of Settlement

The number of Jews in Ukrainian lands which came under Russian rule as a result of the Second (1793) and Third (1795) Partitions of Poland was somewhere between 400,000 and 500,000. They were part of former Polish-Lithuanian territory, which in the Russian Empire came to be known as the Pale of Jewish Settlement. Initially, the imperial Russian regime sought ways to integrate the Jews by legalizing their residence (previously forbidden in Russia), although only in the fifteen new western provinces of the empire that composed the Pale. The enlightened yet authoritarian Empress Catherine II allowed Jews to become part of imperial Russia's social estates, in particular townspeople (meshchane) and merchants (kuptsy), thereby fulfilling the spirit of eighteenth-century utilitarianism in which Jews were classified predominantly as an urban population. The imperial authorities encouraged, although with little success, Jewish agricultural colonies, and they attempted throughout the nineteenth century to outlaw the role of Jews as middlemen in rural areas. In an attempt to utilize Jews as entrepreneurial craftsmen and merchants, the tsarist government fostered Jewish resettlement to the underpopulated regions of the southern Ukraine (Kherson, Katerynoslav, and the newly founded Odessa), and it also allowed Jews to settle in the western fortress town of Kamyanets-Podilskyi, from which they had previously been banned by the Polish authorities.

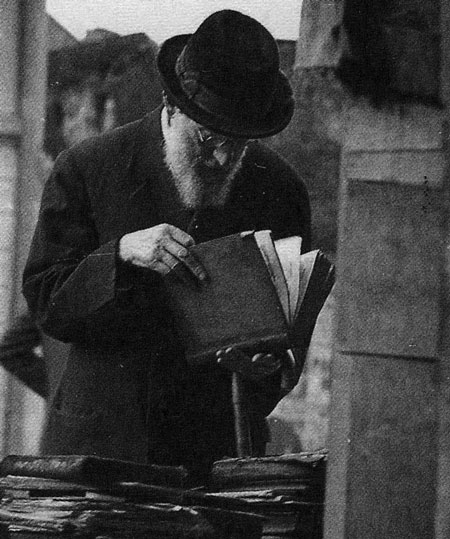

The imperial regime planned to refashion Jewish communities into a sort of corporate entity along the lines of what was known as Russia's "bar-rack enlightenment," that is, extending equal duties without offering equal rights (which nobody had), which would eliminate the barriers that separated them from other groups of the population. To this end, Tsar Nicholas I (r. 1825–1855) included Jews in the military conscription pool, seeking through the army to transform them into loyal and useful subjects. Clumsily imitating similar reforms in western Europe, especially in Prussia, Nicholas also ordered state-sponsored secular elementary Jewish schools to train students to read and write in Russian, while at the same time encouraging the newly established rabbinic seminary in Zhytomyr to create a group of Jewish crown rabbis (kazennye ravviny) who would function as docile Jewish clerks responsible for maintaining vital communal records. These new structures drew heavily from a very limited but slowly growing number of enlightened Jews, the so-called maskilim (derivative of Heb. Haskalah — Enlightenment), who championed rapprochement with the rest of imperial Russia's inhabitants through a process of assimilation. At the time, all these measures were understood to be part of a positive legal, educational, and social phenomenon that would result in the integration of Jews into the broader society.

Throughout the nineteenth century, the enlighteners repeatedly called on the tsarist government to reform, radically if necessary, the Jewish community. They hoped that traditionally minded Jews would reject their obscurantist rituals and instead adopt the cultural values of the surrounding non-Jewish population, particularly in the realm of education. Some of the enlighteners joined the staff of the Zhytomyr rabbinic seminary, while others became so-called expert Jews (uchenye evrei) serving as advisers to regional tsarist governors or as censors of Jewish books.

From the ranks of enlightened Jews emerged the first eastern European Jewish journalists and writers, whose works began to appear in the 1860s during the era of Great Reforms under Tsar Alexander II (r. 1855–1881). This was also a time when the first Hebrew, Yiddish, and Russian-Jewish newspapers were published in the Russian Empire. The first generation of Jewish journalists, censors, crown rabbis, doctors, and lawyers who obtained their degrees at the rabbinic seminaries and Russian universities formed the core of what would become known as the eastern European Jewish intelligentsia. Most, although not all, of its representatives aspired for cultural empowerment and, therefore, chose integration into the state-based imperial culture. Consequently, they were usually called Russian Jews, even though many were from Ukraine and had a strong admiration for that land and its Ukrainian language and culture.

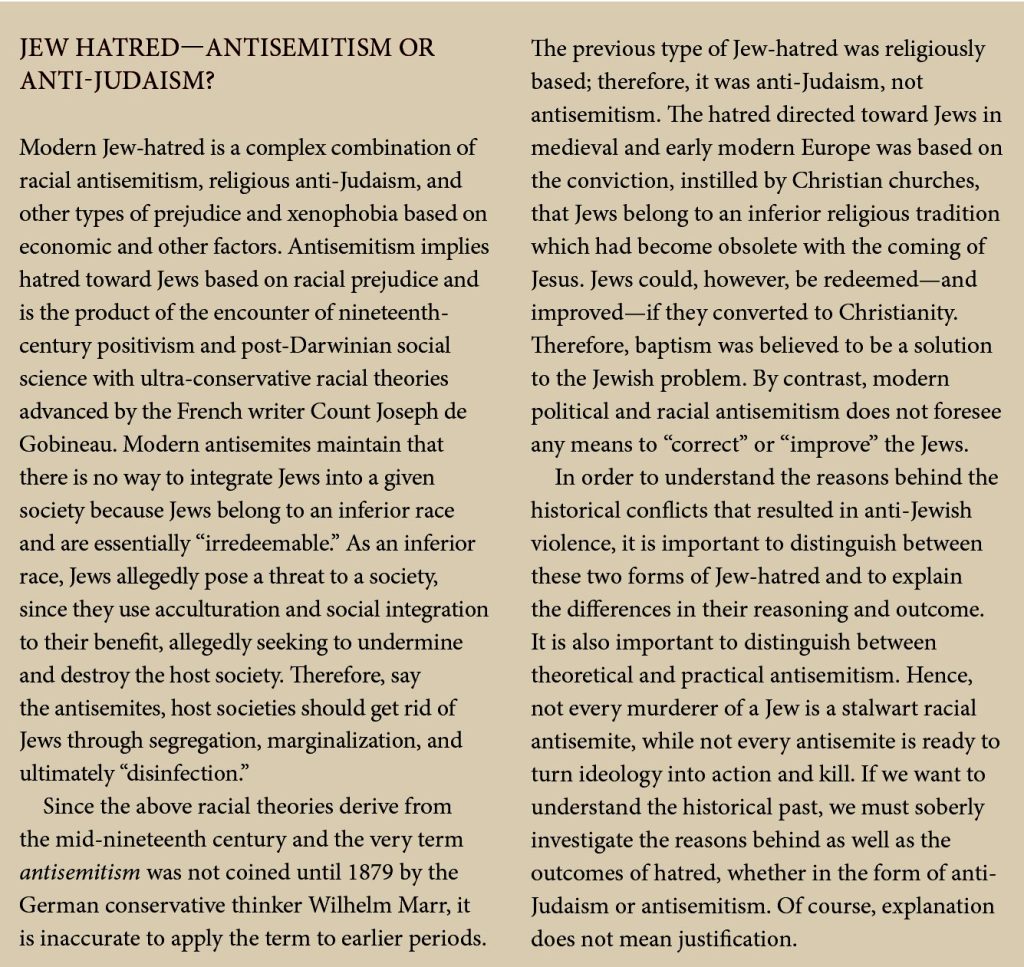

When, during the 1870s and 1880s, the Russian imperial regime embarked on a program of intensive industrialization, this soon resulted in an exacerbation of socioeconomic tensions in the new urban centers, particularly in southeastern Ukraine. The assassination in March 1881 of Alexander II, remembered as the tsar-liberator who abolished serfdom, contributed to creating an atmosphere of political uncertainty and social tension throughout much of the Russian Empire. It was in this context that village peasants and mobs of first-generation urban dwellers took out their anger in a series of pogroms against Jewish residences and stores in three dozen towns and cities and over two hundred villages. The worst instances occurred in Yelyzavethrad, Katerynoslav, Berdyansk, Kyiv, Mykolayiv, and Kherson in central and southern Ukraine. The number of deaths as a result of the 1881–1882 pogroms was small, perhaps 50, of whom half were the pogromists themselves, killed by the troops sent to quell the riots. The material damage to Jewish-owned stores and trading-stalls that were looted was enormous, however. Jewish losses amounted to hundreds of thousands of rubles, whereas the negative impact of the mob violence on the Russian economy in general was estimated to be about 15 million rubles.

Despite false assumptions at the time that the government had instigated the pogroms of 1881–1882, the imperial authorities did their best to check further outbursts of mass ethnic anti-Jewish violence. Rumors that a secret society of landlords, police, or some governmental body had prepared and carried out the pogrom activities proved to be false. Nonetheless, newly appointed Minister of Interior Nikolai Ignatiev, instead of looking into the growing unrest in the country's rural areas, chose to label the Jews as exploiters who were themselves allegedly responsible for the anti-Jewish violence. The Russian conservative press not only supported and disseminated this distorted viewpoint, it also circulated rumors of alleged anti-Christian hatred of the Jews. All of this provided a new vocabulary of racial hatred and contributed to creating a new form of antisemitic discourse in tsarist Russia.

The pogroms of the 1880s have traditionally been viewed by historians as a so-called watershed in eastern European Jewish life. They are considered to be a major contributing factor to the massive emigration of Jews from the Russian Empire abroad, most especially to the northeast United States. The pogroms have also been seen as a galvanizing force for new political movements among Jews, whether those who hoped to transform Russian society (the socialist Bund) or those who wished to leave it entirely (the Zionists). Such views are not supported, however, by the results of recent scholarship, which instead tends to emphasize the idea of continuity in eastern European Jewish life up until and even through much of World War I.

While most Jews in Ukraine's pogrom-stricken territories remained in their places of residence, some Jews from tsarist-ruled Belarus and Lithuania who did not experience the anti-Jewish violence first-hand nonetheless found themselves in a much worse economic predicament. Hence, they decided to take to the road. In 1881 about three thousand tried to cross into Austria-Hungary at the Galician town of Brody, while the following year another twenty thousand sought to leave tsarist Russia. This was the beginning of what became a massive exodus of about two million Jews, who between the 1880s and 1914 left the Russian Empire in hopes of finding a better life whether in the United States, Canada, Argentina, South Africa, and Palestine (the land of Israel). Despite the pogroms in Ukrainian territories in the 1880s and the subsequent worsening economic situation throughout the Russian Empire, Ukrainian Jews began to leave en masse only in the late 1890s and were, therefore, among the last to join the mass migration abroad.

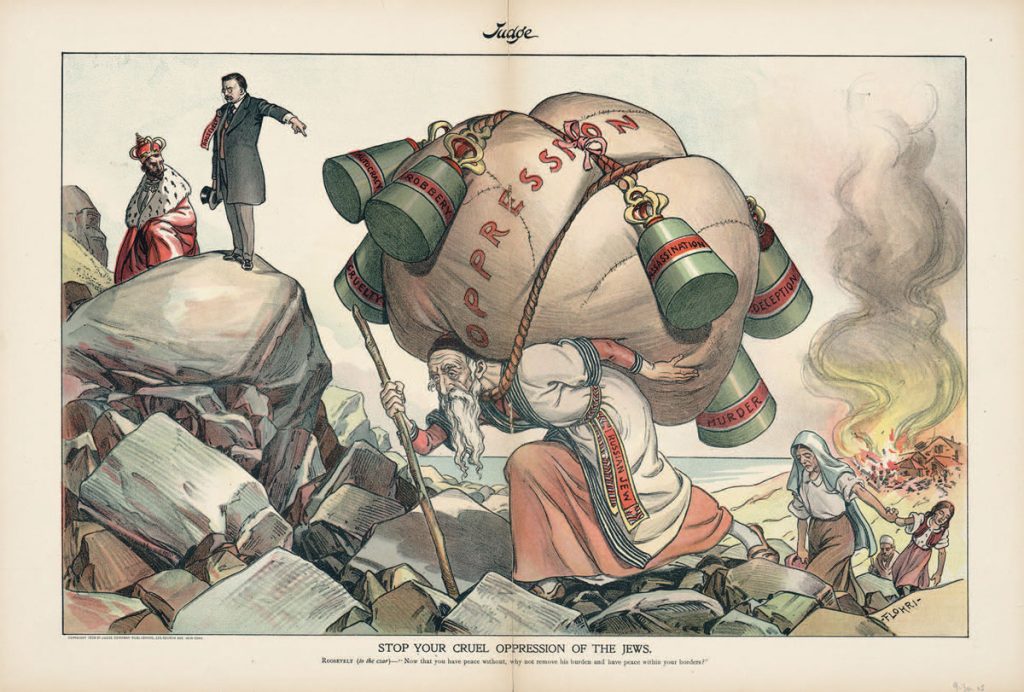

Emigration abroad intensified in the wake of the 1905 Russian Revolution, when the regime of Tsar Nicholas II (r. 1894–1917) — in stark contrast to the previous one during the relatively peaceful years of Alexander III (r. 1881–1894) — purposefully orchestrated and manipulated anti-Jewish violence as a means to check revolutionary activities in the country. Supported by the police and the army (including at times reservists), in 1905 alone pogroms against Jews broke out in more than five hundred towns throughout Russian-ruled Ukraine. They resulted in about a thousand casualties, particularly in Odessa, Katerynoslav, Kyiv, and Kishinev/Chișinău, and in more than 50 million rubles in property damage. The sinister role of the government of Nicholas II in instigating the mass violence did not go unnoticed in Europe and in the United States, where public opinion was highly critical of the Russian imperial regime and sympathetic to the plight of the oppressed Jews.

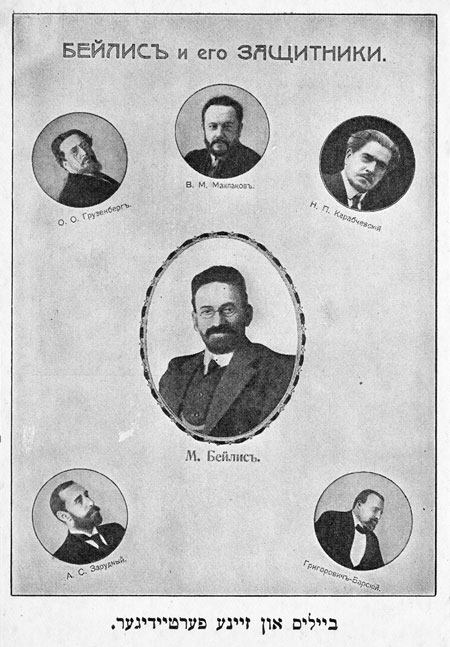

On the eve of World War I, Kyiv became a testing ground for Russia's far-rightist elements in their efforts to turn the local population and the tsarist government against the Jews and, thereby, to end once and for all further discussions of liberal reforms and projects of Jewish emancipation. The murder in 1911 of a twelve-year-old boy, Andrii Yushchynskyi, by a Kyiv criminal gang under the guidance of Vera Cheberyak, the mother of one of the child's friends, served as a call to action for xenophobic groups. The most prominent of them was the Union of the Russian People, which launched a vociferous campaign based on a false blood-libel accusation against Menahem Mendel Beilis, a clerk at a brick plant situated near the cave where the tortured body of Yushchynskyi was found.

Although Beilis was a Russian army veteran who enjoyed excellent relations with Kyiv's Christian Orthodox community and even with some stalwart xenophobes, several far-right activists (in particular the militaristic Black Hundreds) managed to convince the government to reclassify the crime as a blood libel. They proposed that Beilis be tried as a religious fanatic and criminal who allegedly murdered a Christian boy in order to extract blood that was subsequently used to bake Passover matzo. When the trial began in 1913, Russian lawyers represented the defense, while the Russian writer from Ukraine, Vladimir Korolenko, who was sympathetic to Beilis, covered the case for the democratic press. Notwithstanding the seemingly biased court and the blatant antisemitic hysteria on the pages of the conservative press, the jury, selected mostly from local Ukrainian peasants, found Beilis innocent but nevertheless upheld the view that the killing was an act of ritual murder.

The growing economic tensions, curtailed reforms, and new anti-Jewish legislation dating from the 1880s prompted another kind of response. Many Jews joined various socialist circles and parties, ranging in political orientation from socialist-revolutionary and social-democratic to Zionist, Poalei Tsion (Marxist Zionist), Folkspartai (national autonomist), and Bundist (Jewish social-democratic). In Ukrainian lands, political radicalization had a much lesser impact than it did in the more industrialized regions of tsarist-ruled Lithuania and Poland. Nonetheless, Jews in Ukraine did participate in public life across the political spectrum, often supporting both Bundists and their staunch enemies, the Zionists. In actual practice, concrete political allegiances were less important than activism in and of itself, a sign of the coming of age of Jews as a political nation. In the end, however, the vast majority of the Jewish population in Russian-ruled Ukraine and elsewhere throughout the tsarist empire remained apolitical and much more concerned with daily economic needs. Hence, the Jews of the Russian Empire were caught by surprise when World War I and the revolutions of 1917 left them faced with multiple accusations of disloyalty originating from the country's radically differing political leaders and military commanders, each pursuing his own agenda.

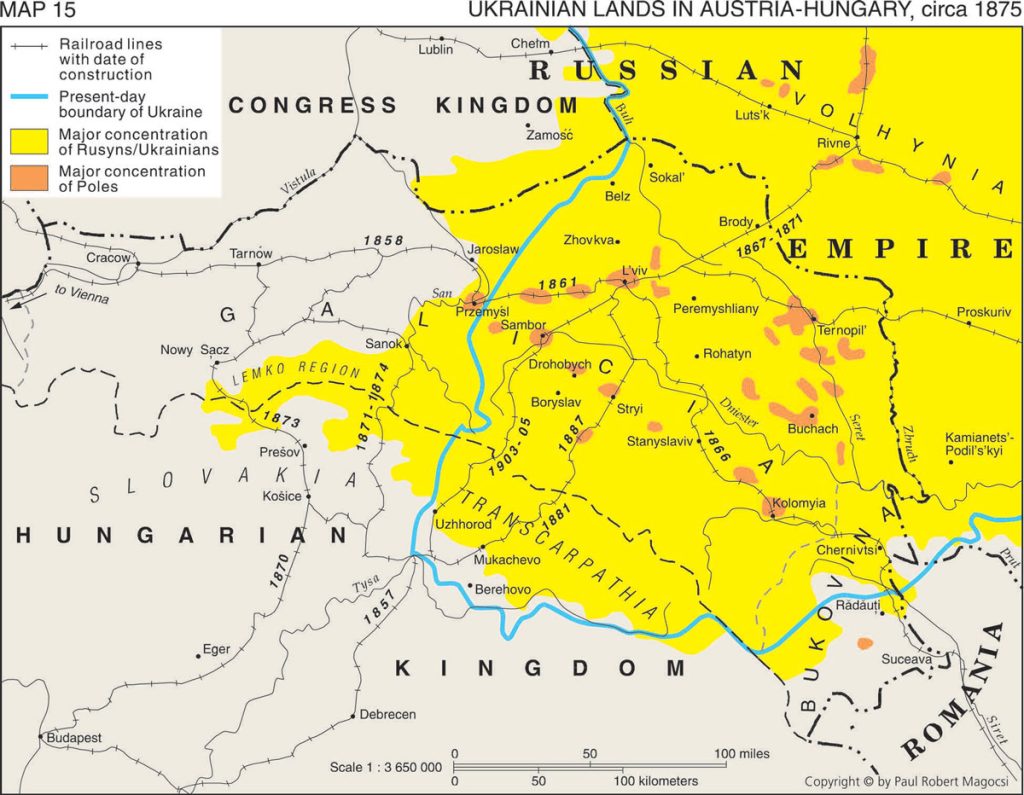

Ukrainian lands in the Austro-Hungarian Empire

In the neighboring nineteenth-century Austrian Empire, which accounted for only about 15 percent of present-day Ukraine's territory, the administrative structure was quite different. The empire, which after 1868 was renamed the Austro-Hungarian Dual Monarchy, was divided into two territorially uneven "halves": the provinces of Austria (which eventually numbered seventeen) and the Kingdom of Hungary. The state was headed by a ruler of the House of Habsburg, who was simultaneously emperor of Austria and king of Hungary. Habsburg lands that are currently in Ukraine consisted of the eastern part of the province of Galicia and the northern part of the province of Bukovina, both of which were in the empire's Austrian half; and several counties in the northeastern corner of the Hungarian Kingdom, which today comprise the Transcarpathian oblast of Ukraine.

tolerant Austro-Hungarian Empire from 1848 to 1916. Photo,

1865.

The demographic composition of Galicia, Bukovina, and Transcarpathia was mixed. Even in those areas where ethnic Ukrainians (officially known as Ruthenians) formed the majority population, there were as well other peoples who lived among them, whether in the cities or in the rural countryside. These included Poles and Austro-Germans in eastern Galicia; Romanians and Austro-Germans in Bukovina; Magyars/Hungarians in Transcarpathia; and Jews, who formed a significant portion of the population — especially in towns and cities — in all three regions (see map 13). All these peoples experienced a significant demographic growth in the course of the "long" nineteenth century; in the case of Ruthenians/Ukrainians, from about 1.3 million in the 1780s to 4.3 million in the 1910.

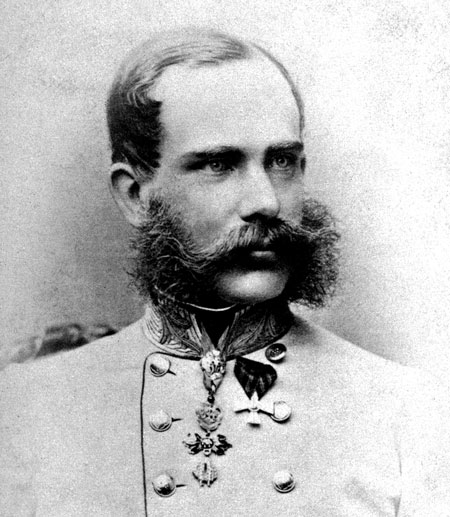

Initially, Austria-Hungary, like Russia, was an empire in which ultimate authority rested in the hands of a hereditary monarch. Habsburg rule gradually came to differ, however, most especially during the long reign of Emperor Franz Joseph (r. 1848–1916). In 1848, on the eve of his coming to the throne, Austria-Hungary was rocked by revolution, during which the largest proportion of Austria-Hungary's inhabitants, proprietary serfs, were legally emancipated. Thereafter, many were able to become economically independent of their former landlords and were even able — and did — participate in government. This is because, from the 1860s, the empire's Austrian "half" functioned as a constitutional monarchy with a national parliament and provincial diets whose members were elected by property owners (including former proprietary serfs). Therefore, the provincial diets and county administrations in both Galicia and Bukovina had ethnic Ukrainian and Jewish deputies, as did the imperial parliament which came into being in Vienna after 1867.

Despite overall improvements in the political and legal status of Austria-Hungary's inhabitants, Galicia, Bukovina, and Transcarpathia remained regions comprised primarily of rural farms and forests, in which the vast majority of the inhabitants gained their livelihood from small-scale agriculture, dairy farming, animal husbandry, and forest-related work, especially in the Carpathian Mountains. With the exception of a small but vibrant oil industry in Galicia, industrial development was very limited. Such an underdeveloped agrarian-based economy was unable to provide an adequate livelihood for the rapidly growing numbers among Austria-Hungary's many peoples, including ethnic Ruthenians/Ukrainians. The result was large-scale emigration abroad during the decades between 1880 and 1914, especially to the industrial regions of the northeast United States and the prairie provinces of western Canada. Rural poverty in Ukrainian lands of the Russian Empire also prompted migration, although very few of Russia's ethnic Ukrainians went to North America. Instead, they resettled in the far eastern regions of the Russian Empire.

Jews of Galicia, Bukovina, and Transcarpathia

As in Russian Empire, Jews in the Habsburg Empire — specifically in the Austrian provinces of Galicia and Bukovina and in Hungarian Transcarpathia — experienced a dramatic demographic increase during the course of the long nineteenth century. If, for instance, in 1790 they numbered about 180,000 in Habsburg territories that are now part of Ukraine, in 1910 their numbers had increased nearly fivefold to 849,000. In Austrian Galicia east of the San River, that is, in the otherwise heavily inhabited Ukrainian part of the province, there were in 1910 over 660,000 Jews, which represented 13 percent of all the inhabitants and more than 30 percent of the urban population. Whereas half a dozen Galician towns had populations with a Jewish majority, about 40 percent of Galicia's Jews resided in the country-side where they were active as mediators in trade.

In contrast to Russia's imperial authorities, who dealt with the Jewish enlightened reformers (maskilim) and appointed them to various state-paid positions related to the community, the Habsburg rulers did not trust the maskilim and cooperated instead with the more conservative Hasidic leaders. The region's Jewish population was quite diverse, particularly in such East Galician cities as Lviv and Ternopil, where they constituted more than two-thirds of all those in the liberal professions (doctors, lawyers, teachers). In rural areas, where Jews from the late 1860s were allowed to own land, they constituted about 20 percent of all landowners. The majority, however, lived in relative poverty and in the traditional Hasidic fashion. They were particularly devoted to their leaders, so that the masters of Hasidic communities (tsadikim) in Sadhora (Sadagora) in Bukovina, Mukachevo (Munkatsh) in Transcarpathia, and Belz, Rymanów (Rimenev), and Nowy Sącz (Sandz/Tsanz) in Galicia had a towering presence and performed a significant role in communal life.

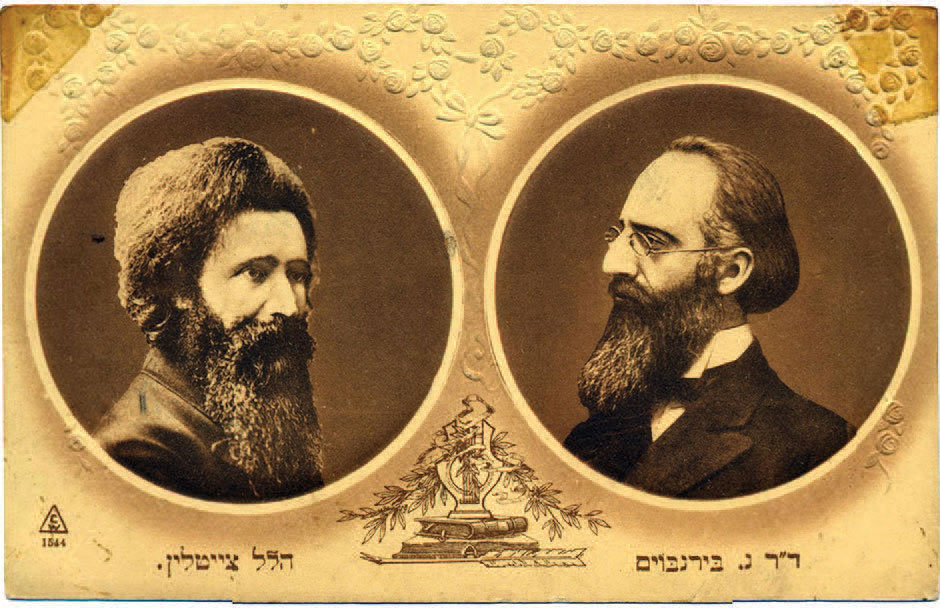

Galician Jews saw themselves caught in the growing rivalry between, on the one hand, Ruthenian/Ukrainian and Polish peasants and urban workers; and, on the other, Poles, who held the province's leading position as landowners and heads of administration. The Poles were ever concerned with the rise of local Ukrainian nationalism and sought to contain its leaders' demands for political and cultural autonomy. These issues became particularly significant once Jews and ethnic Ukrainians gained emancipation from serfdom in 1848 and once universal male suffrage was introduced in 1906. Subsequently, the Jewish electorate often was a decisive factor in the struggle between Ruthenians/Ukrainians and Poles for seats in the Austrian imperial parliament. Resorting to intimidation and sometimes violence, the local Polish administration attempted, sometimes successfully, to convince Jews to vote for Polish candidates or to support those Jewish candidates who favored an assimilationist Polish agenda. There were, however, times when Jews and Ukrainians came together in support of candidates with specific national minority claims and programs. For example, in 1906–1907, Galicia's Ukrainian National Democrats and the Jewish National Party agreed to vote for one another's candidates in those electoral districts with either a majority Ukrainian or Jewish population. Although Jews and Ukrainians often found it difficult to support unanimously the decisions of their respective political leaders, and even more so to implement consistently whatever decision might be adopted, the result was the appearance — for the first time in history — of Jewish and Ukrainian political clubs in the Austrian imperial parliament. The presence of Benno Straucher, a pro-Ukrainian Jewish parliamentary deputy from Bukovina, reinforced the success of the Jewish-Ukrainian political coalition, which worked productively during the full parliamentary session of 1907–1911.

Parliamentary deputies of the Jewish National Party were, in fact, refurbished Zionists. In other words, they opposed local Jewish assimilationists who argued for Jewish integration into Polish culture, and they ridiculed the political efforts of the Jewish Austro-Germanophiles. Instead, they developed a distinct type of Zionism. It was Jewish diaspora nationalism, which worked toward attaining Jewish minority rights and improvement of the social conditions of the Jews in Austria-Hungary rather than emigration to the land of Israel. Taking their cue from Ukrainian nationalists, Galician Zionists attempted to transform the Jews in the diaspora from a religious-ethnic group into a modern nation by rallying them around national democratic slogans.

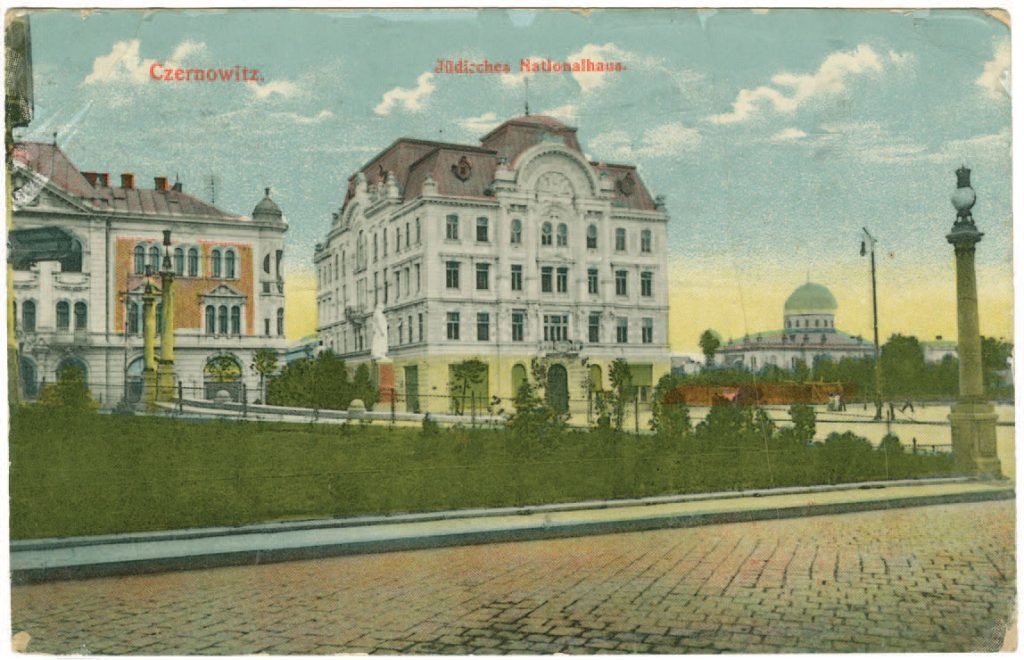

The situation of the Jews in neighboring Bukovina was similar to that in Galicia (of which it was a part until 1861). Bukovinian Jews increased in number during the nineteenth century even more dramatically than in Galicia: from about 3,000 people in 1776 to 102,000 in 1910. These figures represented not only a natural demographic increase but also an influx of Jewish migrants from the Russian Empire and from neighboring Galicia, which the Habsburg authorities tried but ultimately failed to control. Comprising nearly 13 percent of Bukovina's population in 1910, the Jews found themselves between two other competing minority groups — the Romanians (34 percent) and the Ukrainians (38 percent).

Jews lived in Bukovina's few urban areas, where they were particularly active in artisan manufacturing, trade, tavern-keeping, construction, and small-scale banking, all of which reflected their pivotal role in the development of capitalism in this otherwise predominantly agricultural and underdeveloped province of Habsburg Austria. Jews from smaller towns who belonged to lower social estates were less active in capitalist pursuits and, instead, were part of the traditional agricultural-based economy, serving as middlemen between urban and rural areas. Bukovina's lower-estate Jews, less numerous than the lower-estate Jews of Galicia, lived in relative poverty while being devoted to the courts of their Hasidic masters in Boyany (Boyan), Sadhora (Sadagora), and Vyzhnytsya (Vizhnits).

Beginning in the 1770s, the Habsburg administration launched a campaign to integrate the various ethnic groups of the empire. This included a systematic process of germanization and adaptation to the rules and regulations of the growing Austrian imperial bureaucracy. Habsburg integration seemed to work well among the Jews of Bukovina, so that by the 1830s German had become their language of communication, serving as a lingua franca with the authorities and with the empire's other peoples. Urban Jews, in particular, enthusiastically enrolled their children in German-language public schools, thus furthering Jewish integration. Nevertheless, by the end of the nineteenth century, Yiddish was still the everyday language for 85 percent of Bukovina's Jews.

The Habsburgs empowered germanized Jews with higher-education degrees by giving them positions as state clerks, lawyers, and doctors, and by encouraging their election to town councils, provincial diets, and even the imperial parliament. With the rise of various forms of Jewish political involvement, two parties on opposite sides of the political spectrum competed for the support of Bukovina's Jewish voters: the Zionists and the socialist-Bundists. Acknowledging the important role of the Jewish community in Bukovina, the Habsburg administration endorsed the establishment of the Jewish National Center, erected in 1908 alongside the Romanian and German national centers in the very heart of the provincial capital of Chernivtsi.

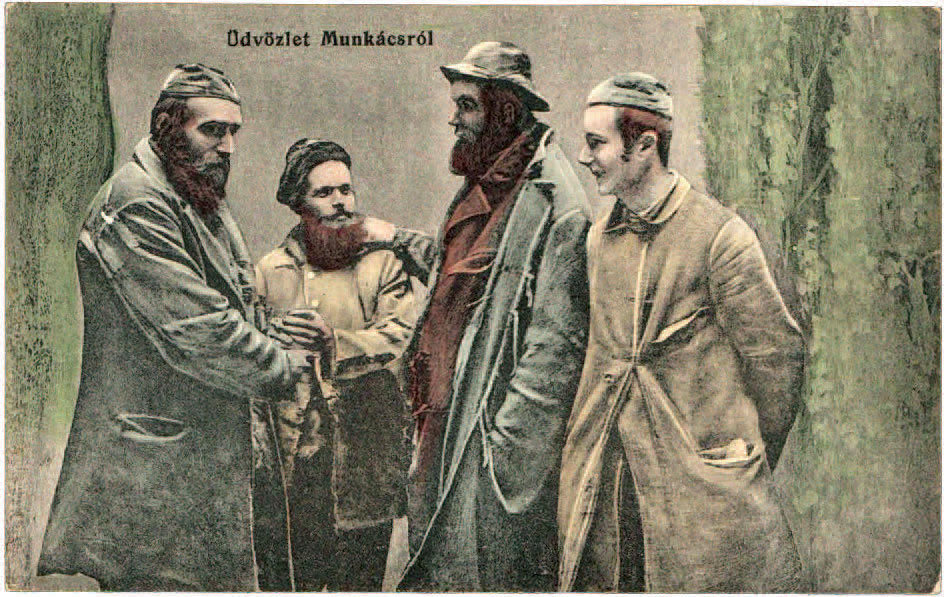

In Habsburg-ruled Hungarian Transcarpathia, the demographic growth of the Jewish population was even more dramatic than in Austrian Galicia and Bukovina. Whereas in 1785 there were a mere 2,000 Jews in Transcarpathia, by 1910 their number had risen to over 87,000. Most were concentrated in Hungary's counties of Maramorosh (51 percent) and Bereg (26 percent). Originating from Galicia to the north as well as from Slovakia in the west, the Jewish settlers quickly adapted to the rural environment dominated by the Carpathian Mountains and foothills.

In contrast to most other parts of central and eastern Europe, most Transcarpathian Jews lived in the rural countryside, where they owned and worked the land alongside their Rusyn/Ruthenian neighbors. They also shared socio-cultural characteristics with their Christian neighbors: most Jews were subsistence-level peasant agriculturalists or lumberjacks, an estimated 30 percent were illiterate, and they were fervently religious Hasidic traditionalists devoted to their so-called wonder-working rabbis (tsadikim), the most influential of which had their dynastic seats in Mukachevo (Munkatsh) and Sighet. Virtually all Transcarpathian Jews were Yiddish-speaking, although rural Jews also spoke Rusyn and urban Jews Hungarian.

It was the Jews' socioeconomic status, so similar to that of their Rusyn/Ruthenian neighbors, that encouraged tolerance and even mutual respect between the two peoples. The Hungarian authorities, however, became increasingly critical of Jews, especially in the 1890s, when a new wave of Jewish migrants fleeing pogroms in the Russian Empire — and joined by economically discontent Jews from Galicia (known in Yiddish as Galitsiyaner) — settled in Transcarpathia's small towns and villages, where they established taverns, inns, and small shops while also lending money to local peasants (Jews as well as Christians) at exorbitant rates. Hungarian commentators were quick to draw distinctions between the older and socially reliable Jewish communities and the newcomers from Galicia, who were blamed in the press for the region's generally poverty-stricken economic status. In an effort to counteract such criticism, many of Transcarpathia's urban Jews welcomed the country's current policy of national assimilation (magyarization) and adopted the Hungarian language and even a Hungarian identity as their own.

In stark contrast to the Russian Empire, where on the eve of the World War I Jews were seen as aliens and increasingly marginalized elements of tsarist society, the Jews of Austria-Hungary were fully emancipated and largely integrated members of Habsburg society. As proud Habsburg subjects, the Jews of Galicia, Bukovina, and Transcarpathia certainly had much better feelings toward "their" emperor, Franz Joseph, than did the Jews of Russian-ruled Ukraine toward Tsar Nicholas II.

(4th from left); second row: Volodymyr Hnatyuk (2nd from left), Mykhailo Hrushevskyi (4th from left), Ivan Franko (5th from left); and

third row: Filaret Kolessa (2nd from left), Ivan Trush (4th from left), and Mykola Ivasyuk (6th from left). Photograph, 1898.

National awakening among Ukrainians

The long nineteenth century was also known as the era of nationalism in Europe, during which several peoples who did not have their own state embarked on what subsequently came to be described as national awakenings. The goal of these multifaceted awakenings was for a given people to acquire an awareness of a national identity expressed often through a distinct language, literary culture, and consciousness of a historic past that was associated with a specific territory and that was deserving of autonomy or, better still, independent statehood.

At various times in this period, the ideology of nationalism reached Ukrainian lands where, interestingly, national awakenings occurred simultaneously among several different peoples, such as the Poles of Galicia, the Romanians of Bukovina, the Jews in those areas and in the Russian-ruled Right Bank, and the Tatars of Crimea. Ukraine, therefore, witnessed simultaneously more than one national awakening, including one that involved the area's numerically dominant population, ethnic Ukrainians.

National awakenings among stateless peoples depended for the most part on each group's self-designated leaders known as the national intelligentsia. These individuals generally included teachers, clergymen, lawyers, doctors, writers, and scholars, in particular historians, linguists, and ethnographers. In the case of ethnic Ukrainians, the most prominent propagators of the national idea were the national bard Taras Shevchenko, the historian Mykola Kostomarov, and the novelist Panteleimon Kulish in the Russian Empire, and the belletrist and scholar Ivan Franko and the historian Mykhailo Hrushevskyi in the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

The success of any national movement depended not only on the effectiveness of the nationalist intelligentsia, but also on the policies of the state. In this regard, the differences between the situation faced by ethnic Ukrainians in the two empires could not have been greater. Whereas until the 1840s the Russian imperial government gave encouragement to what they called Little Russian scholarly and cultural endeavors, subsequently it placed restrictions and tried to suppress the very idea of a distinct Ukrainian nationality. As a result, there were no Ukrainian-language schools and only a few cultural organizations, while publications in Ukrainian were banned by tsarist decrees issued in 1863 and 1871. This situation, with the exception of a brief period after 1905, basically did not change until the very end of tsarist rule in 1917.

In the Austrian Empire, by contrast, the Habsburg rulers gave encouragement to Ruthenian cultural, educational, and religious life in the 1770s and 1780s. But it was the Revolution of 1848 that brought about monumental changes. Not only were Ruthenians/Ukrainians recognized as a distinct nationality, after 1848 they were allowed to form their own civic, cultural, and political organizations, and their children could attend state-supported schools from the elementary through university level in which Ruthenian/Ukrainian was the language of instruction. There were numerous Ukrainian-language newspapers, journals, theaters, economic cooperatives, credit unions, and political parties which helped elect deputies representing Ukrainian national interests to legislative bodies at the county, provincial, and national levels. Finally, in contrast to the Russian Empire, where the Orthodox Church was an instrument of the state and was opposed to any aspect of Ukrainian ideology, Habsburg Austria-Hungary gave its full support to the Uniate (renamed in the 1770s Greek Catholic) Church, which eventually developed into a stronghold of Ukrainian spirituality, language, and culture, in particular after 1900 when the primate of the church was Metropolitan Andrei Sheptytskyi. Whereas the situation in Hungarian Transcarpathia was not favorable to a national awakening, Habsburg-ruled Austrian Galicia (and to a lesser extent Bukovina) provided a positive environment for developments which, by the second half of the long nineteenth century, made possible the very survival of the Ukrainian nationality.

Kyiv, November 1917.

Click here for a pdf of the entire book.