Chapter 2.3: "Jews and Ukrainians: A Millennium of Co-Existence"

Jews and Ukrainians: A Millennium of Co-Existence is an award-winning book that explores the relationship between two of Ukraine’s most historically significant peoples over the centuries.

In its second edition, the book tells the story of Ukrainians and Jews in twelve thematic chapters. Among the themes discussed are geography, history, economic life, traditional culture, religion, language and publications, literature and theater, architecture and art, music, the diaspora, and contemporary Ukraine before Russia’s criminal invasion of the country in 2022.

The book addresses many of the distorted stereotypes, misperceptions, and biases that Ukrainians and Jews have had of each other and sheds new light on highly controversial moments of Ukrainian-Jewish relations. It argues that the historical experience in Ukraine not only divided ethnic Ukrainians and Jews but also brought them together.

The narrative is enhanced by 335 full-color illustrations, 29 maps, and several text inserts that explain specific phenomena or address controversial issues.

The volume is co-authored by Paul Robert Magocsi, Chair of Ukrainian Studies at the University of Toronto, and Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern, Crown Family Professor of Jewish Studies and Professor of History at Northwestern University. The Ukrainian Jewish Encounter sponsored the publication with the support of the Government of Canada.

In keeping with a long literary tradition, UJE will serialize Jews and Ukrainians: A Millennium of Co-Existence over the next several months. Each week, we will present a segment from the book, hoping that readers will learn more about the fascinating land of Ukraine and how ethnic Ukrainians co-existed with their Jewish neighbors. We believe this knowledge will help counter false narratives about Ukraine, fueled by Russian propaganda, that are still too prevalent globally today.

Chapter 2.3

The Historical Past

World War I and the revolutionary era

The first decade of the twentieth century was marked by rising international tensions in Europe, which were subsequently played out in small-scale wars in the Balkans (1912–1913) and in ongoing political rivalries and an armament race between the Great Powers: Great Britain, France, and Russia on one side; and Germany, Austria-Hungary, and Italy on the other. The tensions culminated in August 1914 with the outbreak of what came to be known as the Great War, or later World War I.

Ethnic Ukrainians now suddenly found themselves fighting against each other in armies that were on opposing sides in the conflict: Russia together with Great Britain, France, and eventually Italy and United States on the side of the Allies; and Austria-Hungary together with Germany and eventually the Ottoman Empire on the side of the Central Powers. This division also had an impact on ethnic Ukrainian immigrants in North America, who were suspected of being possible enemy agents of Austria-Hungary, with the result that several thousand in Canada were without any justification forcibly sent to internment camps for the duration of the war.

War and revolution in Ukrainian lands

Ukrainian-inhabited lands, especially in Galicia and Bukovina, were in the center of the Eastern Front and the scene of several major battles. The so-called Carpathian Winter War of 1915 alone cost over a million casualties among the enemy combatants, not to mention the enormous material destruction of the rural countryside and urban areas. Ethnic Ukrainians and other East Slavs from Galicia were considered potential fifth-columnists and interned by the Austro-Hungarian authorities in what became Europe’s first concentration camps.

The first political victim of the enormously costly and destructive Great War was the internally fragile Russian Empire. In 1917 two revolutions took place: the first in February/March toppled the tsar and brought an end to imperial rule; the second in October/November overthrew Russia’s interim Provisional Government and brought to power a regime that aimed to create on the basis of Marxist socialist doctrines the world’s first workers’ state, Soviet Russia. The radically opposed political visions espoused by Russia’s leaders — a western European-style parliamentary democracy versus a system of workers’ and peasants’ councils directed by one political party (Bolshevik and Menshevik factions of the Russian Social Democratic Labor party) — could not be reconciled. The result was armed conflict and civil war between the Bolshevik “Reds,” their opponents dubbed the “Whites,” and numerous other military and paramilitary formations. Added to that was the intervention of Austro-Hungarian, French, German, Polish, and other foreign troops. Hence, while World War I may have come to an end for the Russian Empire, brutal conflict in the form of a civil war was to last for another three years from early 1918 to late 1921. World War I may have come to an end for the Russian Empire, but Russia’s Civil War was to last from 1918 to 1921. When World War I finally concluded with an armistice signed on 11 November 1918, Austria-Hungary ceased to exist. This led to a period of political uncertainty for the many lands and peoples of the former Habsburg Empire that was not fully clarified until 1920.

Ukrainian statehood east and west

During this era of rapid military and political change, ethnic Ukrainians and Ukrainian lands also experienced revolution and civil war. The leaders who had participated in the latter stages of the national awakening during the long nineteenth century now saw an opportunity to realize the ultimate goal of nationalism: independent statehood. In March 1917 Ukrainian activists formed a political body, the Central Rada, which proclaimed the existence of a Ukrainian National Republic, first as an autonomous part of Russia and then, in January 1918, as an independent state. In no way, however, were all the residents of Ukrainian lands in the former Russian Empire desirous of living in an independent or, for that matter, any kind of Ukrainian state.

While the war was still raging, Germany realized the advantages in having an independent Ukraine as its ally. Hence, when Germany and Austria-Hungary reached an agreement with Bolshevik Russia to end the war in the east (Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, March 1918), all signatories to the peace treaty recognized Ukraine as an independent state. Separate economic and trade agreements were signed by Ukraine with Germany and its ally Austro-Hungary. But as soon as Germany felt that Ukraine was unable to fulfill its obligations as an ally, it deposed the Central Rada of the Ukrainian National Republic and, in April 1918, helped install what became known as the Ukrainian State headed by Hetman Pavlo Skoropadskyi. The koropadskyi-led Hetmanate, as the state came to be known, depended on German and Austro-Hungarian support for its survival. When, however, those two states were defeated and World War I ended, Skoropadskyi’s Hetmanate collapsed. In late November 1918 the Ukrainian National Republic was restored and administered by a body known as the Directory, in which the leading and dominant figure soon became Symon Petlyura.

Meanwhile, ethnic Ukrainian leaders in Austria-Hungary undertook their own efforts at state-building. As soon as Austria-Hungary collapsed, on 1 November 1918, Ukrainians took control of Habsburg governmental buildings in Galicia’s provincial capital of Lviv and proclaimed the existence of a West Ukrainian National Republic that was to include what they declared were the solidly Ukrainian-inhabited lands of former Austrian Bukovina, Hungarian Transcarpathia, and most especially Galicia as far west and even beyond the San River. The West Ukrainian declaration of independence prompted an immediate reaction from Galicia’s other dominant group, the Poles. On 1 November 1918 conflict broke out in Lviv between Polish and Ukrainian armed units that within a few weeks evolved into a full-scale war.

Galicia’s Jews, who were otherwise neutral, now found themselves caught between Poles and Ukrainians and having to take sides. Bewildered by the support of some of Lviv’s Jews for the Ukrainian cause, Polish troops entering the city (22 November) orchestrated a bloody pogrom that took lives of some seventy Jews and left about three hundred wounded. The victimization of the Jews at the hands of the Poles resulted in a new level of solidarity with Ukrainians as hundreds of young Jewish men joined the armed forces of the West Ukrainian National Republic. In the Ukrainian Galician Army several Jewish units were formed, including the Jewish Shock Battalion and the Jewish Mounted Machine Gun company, where soldiers such as platoon commander Salko Rotenberg and lieutenant Solomon Lyainberg played key roles in the defense of a hoped-for independent Ukraine.

In the midst of hostilities, the West Ukrainian National Republic formally united with the Ukrainian National Republic in January 1919. The result was the creation — at least on paper — of a United Ukraine (Soborna Ukraïna), a symbolic act hailed at the time and ever since by Ukrainian patriots as the ultimate achievement of the national awakening. The act, however, was little more than symbolic, because in June 1919, after nearly half a year of conflict, Poland’s armies succeeded in driving out the West Ukrainian forces and government. All of Galicia was now under the control of Poland, which itself had only just been restored as a state at the close of World War I. As for Ukraine’s other former Austro-Hungarian lands, Bukovina was annexed to Romania in November 1918, while former Hungarian-ruled Transcarpathia became — as a result of a voluntary declaration in May 1919 — part of the new state of Czechoslovakia.

At the same time that the Polish-Ukrainian war was raging in Galicia, eastern Ukrainian lands in the former Russian Empire entered into a period of chaos and anarchy that was to last throughout all of 1919 and most of 1920. The rivals in the east who claimed Ukraine as their own and fought for its control included: the Ukrainian National Republic under Petlyura; the Ukrainian Socialist Soviet Republic in alliance with Bolshevik Russia; the anti-Bolshevik White armies of General Anton Denikin trying to restore some kind of non-Bolshevik Russian state; and in the far south the Crimean Tatar National Republic. Added to this complicated mix were foreign invaders, whether Poland from the west, French-led Allied forces from the south, or Bolshevik Russia’s Red Army troops from the north, each of which tried to prop up one of the competing governments claiming Ukraine. And if that were not enough, virtually the entire country was being ravaged by peasant-based armed bands led by charismatic and often apolitical otamany/military chieftains (Zelenyi, Hryhoriyev, among others), who represented no particular government. The most famous — or infamous — of the otamany was Nestor Makhno, who did have a political program, although one that hoped to see a future Ukraine governed by the principle of anarchism.

In a word, during 1919 and most of 1920, no government had any long-lasting control over Ukraine, but at best only short-term control over a particular area or city. Not far from the truth was the ironic quip that Petlyura’s Ukrainian National Republic existed on the short strip of railroad track on which the car carrying his government frequently moved in an effort to avoid capture by his enemies.

Out of the caldron that eastern Ukraine had become in 1919–1920, and after all the competing forces were exhausted, it was only the Bolshevik-led Communists who were able to emerge as the long-term victors. Backed by Soviet Russia’s Red Army, and after two previous failed attempts (February 1918 and February-August 1919), the Communist-led Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic was finally, in late 1920, able to establish its authority over most Ukrainian-inhabited lands that had formerly been part of the Russian Empire. Meanwhile, in western Ukraine, that is, former Austria-Hungary, East Galicia was formally granted to Poland in March 1923, whereas even earlier the Paris Peace Conference (Treaty of St Germain, September 1919) recognized Transcarpathia to be a part of Czechoslovakia and Bukovina a part of Romania.

Jews during Ukraine’s revolutionary era

The outbreak of World War I had a devastating impact on Jews in Ukrainian lands within both the Russian and Austro-Hungarian empires. Already in September 1914, the rapidly advancing tsarist troops and the Russian civil administration that was set up in Galicia accused Jews of spying in favor of he Austrians. Taking their Yiddish language for German, the new Russian rulers unleashed horrible violence against Jews, which took the form of mass expulsions from Galicia’s eastern frontier zone into Russia, expropriation of property, and executions for the most part of apolitical Jewish civilians purportedly considered enemies of Mother Russia. When tsarist troops began experiencing heavy losses, their inept commanders, on reporting to the tsar, blamed the Jews living in the Russian-Austrian frontier regions as the reason for their military failures. Thus, military incompetence combined with increasing antisemitism and chauvinism among high-ranking military commanders significantly enhanced the intensity of anti-Jewish atrocities unleashed by the retreating tsarist Russian troops.

Jews viewed without regret the collapse of the tsarist regime during the February 1917 revolution. They expected that the new Provisional Government which came into being would lift all remaining legal restrictions against them, suppress propagandistic racial hatred, establish the rule of law, and protect them from violence. Meanwhile, the nationalist government in Ukraine, with its liberal, democratic-minded, and philosemitic leaders such as Symon Petlyura, Volodymyr Vynnychenko, and Mykhailo Hrushevskyi — who had good intentions but lacked political will — managed to make these first two expectations a reality. Ukraine’s Jews were, indeed, fully emancipated and received the status of national-cultural autonomy centered in their kehillot, or traditional communal institutions. Along with ethnic Ukrainians, otherwise largely unprepared for the unexpected political challenges that faced them, the Jews elected deputies to the Ukrainian Central Rada to represent their interests as a modern nationality. Subsequently, the Ukrainian National Republic created a Ministry for Jewish Affairs and promoted Jewish deputies to leading positions in various governmental ministries. For example, Moshe Zilberfarb and Pinkhas Krasny headed at different times the Ministry of Religion and assumed responsibility for all religious communities in Ukraine, while Arnold Margolin and Solomon Goldelman, respectively as representatives of the Supreme Court and the Ministry of Labor, advanced the Ukrainianization of political life in Ukraine. It is not surprising that Goldelman and Margolin remained loyal to the Ukrainian National Republic government of Petlyura and Vynnychenko for decades after it was forced into exile.

The post-war revolutionary environment was, however, quite volatile. The government of the Ukrainian National Republic had little control over the territory it claimed, which was torn between forces loyal to Soviet Russia (the Reds), to the anti-Bolshevik Volunteer Army (the Whites), to foreign armies (German, Austro-Hungarian, French), or to military chieftains (Makhno, Hryhoriyev, and Zelenyi, among others) who at times allied with the Ukrainian National Republic but did not obey Petlyura’s orders. All these forces crossed the breadth and width of the Ukrainian countryside, where they not only fought against each other but often attacked, pillaged, raped, and murdered at will unprotected villagers and townspeople regardless of their ethno-linguistic background: Germans, Greeks, Mennonites, Poles, ethnic Ukrainians, and Jews.

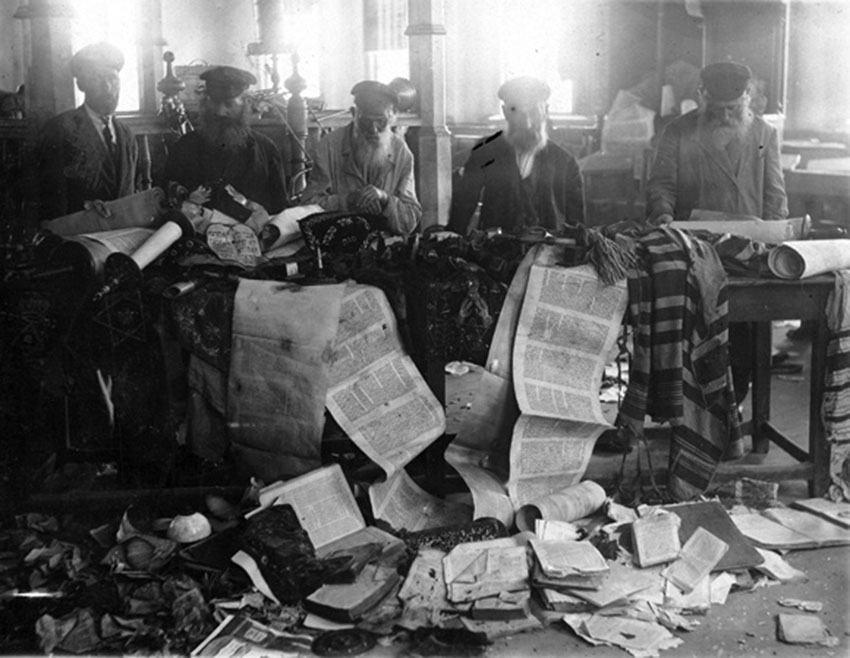

In the case of the Jews, the nadir was reached in 1919. In that year alone — according to estimates calculated by an official in the Ministry of Jewish Affairs in the Ukrainian government — some 1,300 anti-Jewish pogroms took place, resulting in from 50,000 to 60,000 Jews murdered, more than 100,000 orphaned, and about one million displaced. The bloodiest pogroms were orchestrated by Ukrainian National Republic troops in Berdychiv and Zhytomyr, by the White Army under General Denikin in Cherkasy, Fastiv, and Katerynoslav, and by the warlords Ivan Semosenko in Proskuriv (today Khmelnytskyi) and Overko Kuravskyi in Tetiyiv. More than half of all pogroms were attributed to troops loosely connected to various Ukrainian governments, 17 percent to the White Army, 2 percent to the Red Army, and 11 percent to the warlord Hryhoriyev’s troops.

Although Petlyura issued unequivocally strong anti-pogromist proclamations, he could control neither his own troops nor the units led by warlords loosely affiliated with the armies of the Ukrainian National Republic. Although the subsequent acquittal in a French court of Shmuel Schwartzbard (who assassinated Symon Petlyura in Paris in 1926) was widely regarded as an acknowledgment of justified political vengeance, it cannot serve as proof of Petlyura’s personal responsibility for the mass violence against Jews perpetrated by undisciplined and uncontrolled troops under his nominal command. Consequently, as a commander-in-chief of the Ukrainian National Republic’s armed forces, Petlyura may be held accountable for the pogroms of 1919. But as the reputable historian of the period Henry Abramson has maintained, Petlyura was hardly responsible for the pogroms, regardless what subsequent Soviet propaganda and post-Soviet chauvinistic-minded historians have claimed.

The interwar years

Upon the ruins of the Russian Empire, the Bolshevik regime, led initially by Vladimir Lenin, created a one-party Communist state which ostensibly represented the interests of industrial and agricultural workers. In the ideal Soviet world, there were to be no private-owned businesses of any size, no market economy, and agricultural lands were to be transformed into collectivized and state farms. These goals were achieved at various times during the 1920s and 1930s. As for the state’s administrative structure, in December 1922 the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics was formed. It initially consisted of four republics whose number rose to nine before the end of the decade. The republics, each with its own Communist party, were based on the national principle and were intended to serve the cultural needs of the titular nationality whose name each carried. Many of the republics also include within their borders autonomous nationality regions, districts, and villages in which a nationality other than the titular one of a given republic had the right to courts, schools, and cultural institutions which used and promoted their respective languages.

Soviet Ukraine included several levels of nationality subdivisions serving eleven different nationalities, including Russians, Germans, Jews, Poles, and even a small community of Swedes. Despite the existence of national republics, political power was increasingly concentrated in the All-Union Communist-led governmental apparatus based in Moscow, which in effect determined the political, socio-economic, and cultural evolution of the entire country.

Ethnic Ukrainians and Jews in Soviet Ukraine

In an effort to attract more members into the Communist party, Soviet policy makers adopted during the early 1920s a policy called indigenization (korenizatsiya, or rooting), which in the case of non-Russian nationalities was to be carried out through the medium of their own native language. In Soviet Ukraine, one aspect of indigenization, known as Ukrainianization, was implemented fully after 1923 within the framework of what came to known as national communism. Spearheaded by nationally conscious Bolsheviks (Mykola Skrypnyk) and their political allies (Oleksandr Shumskyi), as well as by leftist intellectuals (Mykola Khvylovyi) and the patriotic exiles who returned from central and western Europe, the Ukrainianization program called for all forms of Ukrainian culture — language, history, the performing arts, education — to be promoted with the help of extensive state funding. Other peoples living in Soviet Ukraine also benefited from state funding for analogous “rooting” processes known as Yiddishization, Moldovanization, Hellenization, etc.

The experimental and dynamically productive phase of Soviet rule, which in the 1920s also included a revival of small-scale market trade under a program known as the New Economic Policy (NEP), came to an abrupt end in 1928. In that year, the Soviet Union under Joseph Stalin launched the first stage of a centrally planned command economy. Henceforth, decisions about the economy and all other aspects of society were to be made by the All-Union authorities in Moscow, which, if necessary, would overrule or bypass the governments in the national republics. The main goal of the command economy was rapid industrialization as well as full collectivization — by force if necessary — of all land in the agricultural sector. As a result, Ukraine substantially increased its manufacturing output and raw-material processing from the ever-expanding industrial and mineral extraction sites based in the lower Dnieper valley (the Dnipropetrovsk-Kryvyi Rih-Zaporizhzhya triangle) and the Donbas-Donets basin farther east (Stalino/Donetsk, Luhansk, Shakhty).

State-directed industrialization, carried out in so-called Five-Year Plans, changed the face of Soviet Ukraine’s landscape. Hundreds of thousands of rural farmers were drawn to work in cities, so that between 1920 and 1939 the size of the Soviet Ukraine’s urban population more than doubled and came to represent 36 percent of all the republic’s inhabitants. The agricultural sector proved to be more problematic. The policy of forced collectivization begun in early 1929 resulted in the following: the central planners in Moscow increased production quotas to unrealistic levels; grain and seed was confiscated by soldiers and other security services; well-to-do farmers (kurkuli/kulaks) and anyone who protested were deported to Siberia; and no assistance was forthcoming when a drought in 1932 exacerbated conditions and led to widespread famine. In what became a government-inspired “war” against the rural countryside, an estimated four to five million people starved to death during the Great Famine (Holodomor) of 1932–1933. In response to this human tragedy, not only did the Soviet government refuse to supply or allow from outside any assistance, it simply denied that a famine even happened. Peoples of all nationalities in Soviet Ukraine and neighboring areas to the east were victims of the famine, although by far the largest number was among ethnic Ukrainians who resided in highest concentration in the central, most fertile areas of the country.

Aside from the devastation of the Great Famine, Soviet Ukraine during the remainder of the 1930s was, like the rest of the Soviet Union, transformed into a police state, in which tens of thousands of often innocent individuals, including those who supported or participated in the construction of national communism, were subjected to arrest and persecution. At the same time, cultural developments were hampered by Communist party ideological restrictions, while everyday life for virtually all individuals was characterized by the imposition of government rules and regulations, fear of arrest, and periodic hunger due to food shortages. In these new circumstances, it is perhaps not surprising that all state programs supporting Soviet Ukraine’s various peoples — Ukrainianization, Yiddishization, Polonization, etc. — were abolished in the course of the 1930s.

Initially, the new Bolshevik rulers in Ukraine treated the Jews as a previously victimized minority that under tsarist rule was forced to engage in peddling, trading, and artisan work. In short, Jews were viewed as primarily a petty bourgeoisie in need of social engineering and transformation into productive classes of a socialist society that was promised by the Bolshevik Revolution. Toward that end, the Soviet policy of korenizatsiya (indigenization) sought to create among Jews manageable elites who would be loyal to Communist ideology and then channel that ideology to the Jewish masses in their native language, Yiddish. Socialist-minded Jewish writers, scholars, and journalists arrived in Ukraine from Europe, the United States, and Palestine to participate in this fascinatingly optimistic process of constructing a utopian society which they thought would be free of any ethnic antagonism.

The Soviet Ukrainian government sponsored the establishment of local councils (soviets) and courts with documentation in Yiddish; publishing houses that issued thousands of books in Yiddish; Yiddish theaters; and finally the Jewish Archaeographic Commission at the Ukrainian Academy of Sciences and the Institute of Jewish Proletarian Culture, both in Kyiv. Wooed by influential Ukrainian writers such as Mykola Khvylovyi and politicians such as Mykola Skrypnyk, Jewish elites became active supporters and promoters of the Soviet state and national communism as practiced in Ukraine.

Beginning already during the last years of tsarist rule, many Jews moved from small towns (shtetls) to big cities where they became part of the industrial working proletariat. Many others, however, were still engaged in shopkeeping, artisan crafts, and petty trade, which they were allowed to continue during the New Economic Policy (NEP) era of the 1920s. Bolshevik ideologists saw these Jews in a particularly negative light, as part of the petty bourgeoisie which had no place in the new Soviet society. Therefore, they were classified as lishentsy (disenfranchised), who if necessary should be forced by authorities into the productive labor sector. Ideally, this might be newly organized collective farms, twenty-seven of which were established in southern Ukraine and Crimea. The success of the Jewish colonization project proved to the Soviets — who otherwise ignored the differences between destitute Jews and economically robust Ukrainian peasants unwilling to part with their land — that massive rapid collectivization was feasible.

The Soviets also encouraged upward mobility for the Jews to a degree that was previously unseen in state and government positions in tsarist Russia. More urbanized and therefore better educated than the ethnic Ukrainians, Jews came to occupy leading positions in the industrial, state, and local administration by the end of the 1920s, as well as in the ruling Bolshevik party, the military, and state security services (secret police). Since at the very same time neighboring Poland did not offer its Jews (including those in Galicia) Soviet-style social mobility and government-supported institutional and cultural initiatives, Galician Ukrainians and Poles came to associate the Jews of Soviet Ukraine with Communist power and referred to them derogatorily as the zhydokomuna — understood as the Communist-Jewish conspiracy.

The Great Famine, or Holodomor, that swept Ukraine in 1932–1933 was a severe blow for the hundreds of Jews holding administrative positions in the country’s agricultural sector. Recently declassified secret police documents demonstrate that dozens of local administrators of Jewish descent had been sending alarming reports to the central administration about the horrible situation, but with no result. Many of these regional directors and local party committee secretaries who raised their voice were purged later in the 1930s as enemies of the people.

As part of Stalin’s centralist and dictatorial policies of the 1930s, Soviet authorities launched an offensive against leftist Marxists and supporters of national communism among Jews, ethnic Ukrainians, and other national minorities. Thus, the director of the Institute of the Jewish Proletarian Culture, Yoysef Liberberg, was dismissed and sent to Birobidzhan (then later executed), while the institute itself was shut down and replaced by a much more modest Research Center (Kabinet) of Jewish Culture at the Ukrainian Academy of Sciences. Hundreds of Jews occupying leading positions in the Communist party, in socialist industrial enterprises, and in the state administration, in particular those suspected of leftist ideology or who had non-Bolshevik party affiliations before 1917, were also purged. Consequently, the number of Jews in leading party, state, and administrative positions rapidly diminished by the end of the 1930s.

Ukrainians and Jews in Polish-ruled Galicia

Western Ukrainian lands followed an entirely different evolutionary path during the interwar decades. The Ukrainians in Poland, especially those in Galicia, fared worse than when they had lived in the pre-war Austro-Hungarian Habsburg Empire. In the wake of the defeat of the West Ukrainian National Republic in 1919, Galicia’s Ukrainians adopted three differing approaches to the reality they faced of living in Poland.

The first approach was representative of the majority of Galicia’s Ukrainians. These were the rural dwellers, whose leaders emphasized building a strong economic base in Ukrainian communities through the expansion of agricultural cooperatives and credit unions that dated from the pre-war Habsburg days. Certain agricultural sectors were able to thrive, even during the world economic depression of the 1930s.

The second approach was adopted by civic leaders who participated in Poland’s political system and, through legal parliamentary means, tried to improve the status of their people. The most influential body in Galician-Ukrainian society at the time, the Greek Catholic Church still led by Metropolitan Andrei Sheptytskyi, was a strong supporter of the cooperative movement of civic and cultural improvements for Ukrainians through legal participation in Poland’s political institutions.

Greek Catholic Church and revered “patriarch” of Ukrainians

in interwar Polish-ruled Galicia.

The third approach, which at the time represented a minority of Galicia’s Ukrainians (demobilized World War I soldiers and later unemployed university students and other discontented youth), took the form of underground paramilitary groups. The two most important were the Ukrainian Military Organization in the 1920s and the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN) in the 1930s. Both groups carried out sporadic campaigns of sabotage against Polish state property and the assassination of political leaders (both Poles and Ukrainians who worked within the Polish state system). The Polish authorities responded with pacification campaigns against Ukrainian villagers suspected of helping the underground organizations and even set up an internment camp in the 1930s to imprison arrested Ukrainian paramilitary rebels whom they deemed terrorists. Whereas the activity of the Ukrainian underground (actively denounced by most Galician-Ukrainian leaders, especially Metropolitan Sheptytskyi) provoked Polish repressive measures and loss of life, the situation of Ukrainians in Poland was not even remotely as bad as it was for ethnic Ukrainians in the Soviet Union.

The number of Jews living in Ukrainian lands of interwar Poland (eastern Galicia, western Volhynia, and western Polissia) decreased in comparison with the pre-World War I figure. Nevertheless, there were still by 1930 about 705,000 living in Ukrainian-inhabited regions of eastern Poland. Over two-thirds resided in eastern Galicia, the vast majority in cities and towns, with Lviv having the largest number (102,000).

street in Lviv, 1930s.

The fate of Jews living in interwar Poland differed from that of their brethren on the other side of the border in Soviet Ukraine. In contrast to Soviet practice, the Polish authorities left the Jewish communal institutions intact and did not infringe on Jewish religious life. On the other hand, they deeply mistrusted the Jews (as they did Ukrainians) as a hindrance to their goal of reconstituting Poland along the lines of a nation-state with only one titular nationality at its center, the Poles. Therefore, the very presence of numerically large and politically active minority groups, particularly Jews and Ukrainians, was perceived as jeopardizing such nation-state-building goals. Moreover, the Polish authorities knew that the Jews as a previously segregated minority were, at least during the 1920s, the objects of affirmative action in the neighboring Soviet Union. This reality only sharpened Poland’s mistrust of its Jews. Mistrust did not, however, lead to open forms of animosity, since for the time being the local administration included many socialist-oriented officials who were relatively tolerant of peoples other than ethnic Poles.

Some Ukrainians, especially youth, in the 1930s were attracted to the underground Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN) and came under the sway of that group’s most influential ideologist, Dmytro Dontsov. Dontsov’s numerous xenophobic propagandistic tracts, while directed primarily against Poles and Russians, also caught Jews in his rhetorical web. The OUN may not have targeted Jews as the primary enemy. Nevertheless, its anti-Jewish statements fell on receptive ears among Galicia’s Ukrainian youth at a time when they were marginalized and subject to the assimilationist policies of the Polish state.

Ukrainians and Jews in Romanian-ruled Bukovina

Somewhat similar to the situation in Poland was that of Ukrainians living in Romania. Those residing in the former Russian province of Bessarabia, annexed by Romania in 1918, continued their agriculturally based rural existence and were allowed Ukrainian-language schools and cultural organizations. Much different was the state of affairs in Bukovina, which was taken by Romanian troops in late 1918 and then formally recognized as part of Romania by the Treaty of St Germain-en-Laye concluded in September 1919. The status of Ukrainians in Bukovina was significantly worse, especially in comparison to the favorable political, educational, and cultural status they enjoyed when the region was part of the Habsburg-ruled Austro-Hungarian Empire. Under post-war Romania, the region for most of the 1920s was placed under martial law, Ukrainian university programs and cultural institutions were closed, and elementary school education in Ukrainian severely curtailed. All this was justified by a state that after 1924 classified Ukrainians as “Romanians who had lost the native tongue of their ancestors.”

The situation of Jews in interwar Bukovina under Romanian rule was somewhat different, since relations between the region’s two major ethnic groups — Romanians and Ukrainians — were difficult but by no means as strained as those between Poles and Ukrainians in Polish-ruled Galicia. At the time Bukovina was incorporated into Romania, it included more than 92,000 Jews, over 80 percent of whom lived in the northern part of the region which is now part of Ukraine. Initially, the Romanian authorities granted Jews full citizenship and recognized them as a national minority. They were allowed to establish national minority educational institutions, such as the secular Hebrew Tarbut schools, and to engage in political activity. Several parties represented Bukovina’s Jews: the National party, with its claims for national-cultural autonomy attracting a middle-class constituency; the Bund, with its socialist slogans and working-class constituency; and the Agudas Yisroel, representing the interests of religious Jews (Orthodox and ultra-Orthodox).

These various cultural and political groups were still debating the merits of Romanian cultural integration when, in the second half of the 1930s, the situation for Jews rapidly deteriorated. In 1937 the Romanian authorities co-opted and empowered far-right ideologists who began the legal process of segregating Jews, including the revocation of citizenship of those who acquired it only after 1924. Then, in 1939, thousands of Jews faced the possibility of losing their businesses unless they hired ethnic Romanians, representatives of the country’s titular nation, as co-managers. The practical result was the removal of hundreds of Jews from management positions in industry and banking enterprises, policies that paralleled the introduction of racial laws in Nazi Germany. In short, the increasingly racist Romanian authorities began treating the Jews as agents of an alleged international Communist conspiracy and eventually blaming them for the Soviet annexation of northern Bukovina (including Chernivtsi) during the initial stages of World War II.

Carpatho-Rusyns and Jews in Czechoslovakia

In stark contrast to the situation among Ukrainians in Romania and Poland, the fate of the Rusyn/Ruthenian population annexed in 1919 to the new state of Czechoslovakia was decidedly much more favorable. The democratic and generally liberal environment created by the Czechoslovak regime allowed the local Carpatho-Rusyn populace to foster its own cultural and religious interests in the absence of state-inspired assimilationist policies that were characteristic of the pre-war Hungarian regime. For example, the historically dominant Greek Catholic Church was challenged by a wide-spread return-to-Orthodoxy movement, with the result that by the end of 1920s it had attracted to its ranks nearly one-quarter (100,000) Carpatho-Rusyns. Another challenge that faced civic and cultural leaders was to define the national identity of the region’s East Slavic inhabitants: Were they part of the Russian nationality, the Ukrainian nationality, or a distinct Carpatho-Rusyn/Ruthenian nationality? This question was never definitively resolved during the two decades of interwar Czechoslovak rule.

Czechoslovakia was obliged by international treaty to create an autonomous province called Subcarpathian Rus’/Ruthenia (the present-day Transcarpathian oblast of Ukraine), in which Carpatho-Rusyns functioned alongside Czechs and Slovaks as one of the country’s founding nationalities. Therefore, they enjoyed parliamentary representation determined by democratic elections, education in their native language, and a wide range of civic, cultural, and religious organizations basically unhampered by interference and in many cases financially supported by the Czechoslovak authorities. The numerically dominant Carpatho-Rusyns continued to live in harmony with local Magyars, Jews, and other peoples who comprised 35 percent of the province’s inhabitants.

Czechoslovak rule also proved to be advantageous for the Jews of Subcarpathian Rus’/ Transcarpathia. The new state’s liberal secular-oriented ideals posed certain challenges, however, most especially to the traditionally minded Orthodox Hasidim in rural villages, where more than two-thirds of the region’s 102,000 Jews lived. As for the other third, they inhabited several small towns and cities, where in many cases they made up a plurality of the inhabitants: Solotvyno (44 percent), Bushtyno (36 percent), and Irshava (36 percent). The largest single community, however, was in the city of Mukachevo/Munkatsch (43 percent Jewish) with its suburb Rosvygovo (38 percent) which functioned as the premier cultural and spiritual center of the region’s Jewry.

With regard to that portion of Transcarpathia’s urban Jews who spoke Hungarian and who before the war had adopted a Hungarian identity, they were initially skeptical of the Czechoslovak regime. Nevertheless, within a few years they, like their rural brethren, adapted to the new political environment and actively enrolled their children in Czech-language and, to a lesser degree, Rusyn-language schools. Although the state formally recognized Jews as a nationality with a wide range of minority rights, no more than 10 percent sent their children to the Hebrew-language elementary and senior high (gymnasia) schools made available to them. One reason for their reluctance on this matter was the conservative attitude of the region’s all-powerful Hasidic rebbes, who were different from ordinary rabbis in that they were also spiritual leaders (tsadikim). The most influential of interwar Transcarpathia’s rebbes was Hayim Elazar Shapira of Mukachevo/Munkatsh. He and some his rabbinic colleagues were opposed to the Hebrew-language schools, because they were usually established and run by secular Zionists. In fact, Jewish life in inter-war Czechoslovak-ruled Transcarpathia was characterized, on the one hand, by favorable relations with their Carpatho-Rusyn neighbors, and, on the other, by fierce internal struggles among various Hasidic dynastic leaders as well as between all the Hasidim and what from their perspective were the irreligious Zionists.

Click here for a pdf of the entire book.