Chapter 2.4: "Jews and Ukrainians: A Millennium of Co-Existence"

Jews and Ukrainians: A Millennium of Co-Existence is an award-winning book that explores the relationship between two of Ukraine’s most historically significant peoples over the centuries.

In its second edition, the book tells the story of Ukrainians and Jews in twelve thematic chapters. Among the themes discussed are geography, history, economic life, traditional culture, religion, language and publications, literature and theater, architecture and art, music, the diaspora, and contemporary Ukraine before Russia’s criminal invasion of the country in 2022.

The book addresses many of the distorted stereotypes, misperceptions, and biases that Ukrainians and Jews have had of each other and sheds new light on highly controversial moments of Ukrainian-Jewish relations. It argues that the historical experience in Ukraine not only divided ethnic Ukrainians and Jews but also brought them together.

The narrative is enhanced by 335 full-color illustrations, 29 maps, and several text inserts that explain specific phenomena or address controversial issues.

The volume is co-authored by Paul Robert Magocsi, Chair of Ukrainian Studies at the University of Toronto, and Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern, Crown Family Professor of Jewish Studies and Professor of History at Northwestern University. The Ukrainian Jewish Encounter sponsored the publication with the support of the Government of Canada.

In keeping with a long literary tradition, UJE will serialize Jews and Ukrainians: A Millennium of Co-Existence over the next several months. Each week, we will present a segment from the book, hoping that readers will learn more about the fascinating land of Ukraine and how ethnic Ukrainians co-existed with their Jewish neighbors. We believe this knowledge will help counter false narratives about Ukraine, fueled by Russian propaganda, that are still too prevalent globally today.

Chapter 2.4

The Historical Past

World War II and the Holocaust

Former Czechoslovakia, Poland, and Romania

The prelude to what some have called twentieth-century Europe's second civil war occurred in the year 1938, when Nazi Germany under the dictatorial leadership of Adolf Hitler initiated the first stage of the dismemberment of Czechoslovakia. As a result of the Munich Pact (29–30 September 1938), Germany annexed a significant portion of western Czechoslovakia (the so-called Sudetenland), while that state's eastern provinces, Slovakia and Subcarpathian Rus', gained their long-sought autonomy. Within a month of the Munich Pact, Subcarpathia's autonomous government came to be led by a local pro-Ukrainian civic and cultural activist, the Greek Catholic priest Avhustyn Voloshyn, under whose rule as premier Subcarpathian Rus' was renamed Carpatho-Ukraine.

Like Nazi Germany, Hungary had its own territorial designs on Czechoslovakia. Already in November 1938 it succeeded in annexing southern Slovakia and southwestern Carpatho-Ukraine, including the latter's largest cities, Uzhhorod and Mukachevo. What was left of Carpatho-Ukraine survived for only a few months, until in March 1939 Hitler destroyed the rest of Czechoslovakia and at the same time gave his approval for Hungary's annexation of Carpatho-Ukraine. Military units in the service of Carpatho-Ukraine (mostly Ukrainian volunteers from Polish-ruled Galicia) resisted the Hungarian invasion, with the result that the first casualties of World War II in Europe could be said to have occurred in Subcarpathian Rus'/Carpatho-Ukraine. Hungary was to rule what it renamed Subcarpathia throughout most of the war years. Whereas the new regime supported the view that Carpatho-Rusyns were a distinct East Slavic nationality traditionally loyal to Hungary, it persecuted Ukrainian-oriented local activists and banned their organizations.

After Czechoslovakia, Hitler turned to Poland but this move produced much different results. In late August 1939 the heretofore profound political antagonists, Adolf Hitler and Joseph Stalin, approved the conclusion of a non-aggression treaty known as the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact. A secret clause of the pact provided for a German-Soviet demarcation line between the two allies should, by chance, war break out with Poland. On 1 September 1939 Nazi Germany did, indeed, provoke the outbreak of what became World War II with an invasion into Poland. Two weeks later, the Soviet Union followed suit, taking much of eastern Poland up to the demarcation line which ran more or less along the present-day boundary of Poland with Ukraine.

In the midst of such enormous social disruption, those elements in western Ukraine that supported the interwar underground Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists were themselves rent by profound internal conflict. Following the assassination in exile of the OUN leader (Yevhen Konovalets) by a Soviet agent in 1938, his successor, Andrii Melnyk, was challenged by a younger leader, Stepan Bandera. Supporters of both figures were divided over political ideology, namely, to what degree Italian fascism (Melnyk) or German nazism (Bandera) should be the model in the struggle to liberate Ukrainian lands from foreign rule. The German authorities tolerated and at times even encouraged some of the activities of the OUN, which henceforth was divided into two rival and warring factions known as the Melnykites (OUN-M) and Banderites (OUN-B). While both factions continued to exist, after 1941 the Bandera faction, which initially was more German-oriented, steadily came to dominate the activities of the OUN.

On their side of the demarcation line, Soviet ideologists argued that the local inhabitants had requested what was officially termed the reunification of western Ukrainian territories (eastern Galicia and western Volhynia) — during the interwar years purportedly occupied by Poland — with the "Soviet Ukrainian motherland." The "people's request" was formally accepted on 1 November 1939 by the All-Union government in Moscow. The following summer (June 1940), the Soviet Union annexed from Romania Ukrainian-inhabited northern Bukovina and the old tsarist province of Bessarabia, which contained a compact ethnic Ukrainian population at both its southern and northern ends. It was the political alliance with Hitler that allowed the Soviet Union to expand its borders westward and, in the case of Ukraine, to annex virtually all western territories within the present-day country with the exception of Transcarpathia/Carpatho-Ukraine, which remained within Hungary throughout the war.

The impact of Soviet rule on western Ukraine's population was mixed. Small-scale tradespeople (largely but not exclusively Jews) lost their shops, which were nationalized by the state, while over half a million people — Poles in the service of the previous regime, Ukrainian political and civic activists (who had not already fled westward to the German zone beyond the demarcation line), and anyone suspected of real or alleged anti-Soviet attitudes — were deported to Siberia and the Soviet Far East, with many perishing en route or after arriving. The remaining Jews considered themselves lucky not to be under Nazi German rule as in the other parts of former Poland, while most ethnic Ukrainians (including influential interwar politicians and other leaders like the Greek Catholic Metropolitan Andrei Sheptytskyi), aware of the Great Famine and political repression in the Soviet Ukraine during the 1930s, were wary that their fate would worsen.

Jews in western Ukraine under Soviet rule

In practice, Soviet policy toward the Jews in its newly acquired territories varied considerably. On the one hand, the regime arrested and exiled non-Communist political activists and outlawed all traditional communal institutions; on the other, it engaged the services of many urban Jews.

The Soviets quickly realized that in the newly acquired territories, such as former Polish-ruled Galicia, Jews still resided in non-urbanized shtetls and were engaged in traditional occupations. Living in poverty and comprised of a significant percentage of traditional Orthodox Hasidim, Galicia's Jews represented one of the most economically disadvantaged national minority groups. As in Soviet Ukraine in the 1920s, the Bolsheviks now banned Galicia's Zionist and Bundist political organizations, which in the interwar years were very active in Poland. The Soviet authorities dismantled traditional religious and educational institutions; outlawed Hebrew as a bourgeois, nationalistic, and religious language of class enemies; established secular schools; and promoted local secularized Jews conversant in Polish and Ukrainian to administrative positions. The presence of new obedient and diligent local Soviet administrators in particular exacerbated inter-ethnic tensions among Poles, Jews, and Ukrainians.

By 1940, the Jews of East Galicia had once again become a marginalized ethnic group subjected to enforced assimilation: all the umbrella communal organizations such as the kehillot were dismantled, Yiddish schools were replaced by Russian ones, and the last vestiges of private trade were wiped out. Moreover, one's ethnic background once more became the key factor determining social mobility.

By 1939, there were only two Jews in the Ukraine's Supreme Soviet in Kyiv, while their number in state and local administrations was rapidly diminishing; for example, no more than 4 percent of Jews were serving in the Soviet secret police (NKVD) by the time Germany invaded the Soviet Union. Nevertheless, the myth of the Communist Jewish conspiracy, the zhydokomuna, persisted. It was used not only against the Jews of Galicia, but also against Jews in Romanian-controlled southern Bukovina, where Jews were persecuted, arrested, and segregated for allegedly supporting the Soviets and causing Romania to lose the northern half of the region and its main center, Chernivtsi, in the summer of 1940. At the same time, the Soviets segregated and marginalized the Jews of northern Bukovina on a class basis, treating them as representatives of the bourgeoisie, nationalizing their businesses and property, and exiling thousands to Siberia.

Nazi German invasion of the Soviet Union

As it turned out, Soviet rule in western Ukraine was temporary, because less than two years after the August 1939 non-aggression pact with Nazi Germany, Hitler authorized a full-scale invasion of the Soviet Union under the code name Operation Barbarossa. The invasion, which began on 22 June 1941, was so successful that by November virtually all of Soviet Ukraine was under Nazi German control. In the face of the German invasion, the Soviets desperately tried to dismantle or destroy their large-scale heavy industrial infrastructure, and they managed to evacuate 3.8 million people (ethnic Ukrainians, Russians, and an estimated 900,000 Jews among others) eastward to safety. On the other hand, entire Soviet armies capitulated, their soldiers forced into crude German prisoner-of-war camps where millions perished. Hitler did have allies (Hungary, Slovakia, Romania) whose troops — albeit relatively small in number — joined in the invasion of the Soviet Union. The military and political alliance with Nazi Germany was particularly profitable for Romania. Not only was it able to get back northern Bukovina and Bessarabia, it pushed farther beyond the Dniester River into southwestern Ukraine, so that the area known as Transnistria (including the major port city of Odessa) was placed under a Romanian administration. Hence, as the war raged in the east, Ukraine according to its present-day borders was divided between Nazi Germany and its two allies, Romania and Hungary.

The lion's share of Ukrainian territory was in the sphere of Nazi Germany. East Galicia, part of interwar Poland and most recently Soviet Ukraine, was made a district (Distrikt Galizien) of the Generalgouvernement Polen, a territorial entity that was a protectorate of Greater Germany and therefore subject to its Nazi-dominated legal and social order. On the other hand, the bulk of Soviet Ukraine, including former Polish-ruled western Volhynia and Crimea (until then part of Soviet Russia), was administered as a Nazi-German colony called the Reichskommissariat Ukraine. The difference between Greater Germany's protectorate of the Generalgouvernement and its colony, Reichskommissariat Ukraine, was evident in the way the local inhabitants were treated.

Since its establishment in 1933, Nazi Germany was governed by the principle of racial differentiation. Ethnic Ukrainians, pariahs like all Slavic peoples, were classified as inferior subjects (Untermenschen) useful to the degree that they could serve the superior races (Herrenvölker), of which "Aryan" Germans were the ultimate example. On the lowest end of the racial scale were the Jews, the Gypsies/Roma, the physically disabled, and other "social misfits," all of whom were eventually subject to extermination by various forms of murder.

When, in the last week of June 1941, German troops crossed the demarcation line and drove the Soviets out of East Galicia, they were accompanied by small units connected with the interwar underground Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (both its Melnykite and Banderite factions), who were allowed to operate in Nazi German- controlled parts of central and eastern Europe. In cooperation with established Galician-Ukrainian leaders, many of whom had until then opposed what they considered the violent extremism of the OUN, activists of the Banderite faction led by Yaroslav Stetsko proclaimed in Lviv the "restoration" of a Ukrainian state on 30 June 1941. This unauthorized AKT, as it was known, resulted in several unintended consequences: the arrest of nationalist leaders (including Stetsko and Stepan Bandera) who then spent the rest of the war in German prisons; the suppression of OUN activists of both factions; and the eventual alienation of Galician-Ukrainian moderate political leaders from what they came to realize was the brutality of Nazi rule.

As the war grinded on, that brutality took different forms: forced deportation of 2.3 million young ethnic Ukrainians to work in Greater Germany (Ostarbeiter); the slow starvation to death of Soviet prisoners-of-war; military reprisals against the civilian population suspected of aiding anti-German partisans; and the wholesale persecution and murder of Jews, whether they lived in territories ruled by Nazi Germany (Generalgouvernement and Reichskommissariat Ukraine), Romania (Bukovina, Bessarabia, and Transnistria), or Hungary (Subcarpathian Rus'/Transcarpathia).

The Holocaust in occupied Ukrainian lands

From the very outset, the Nazis pointed to Jews as enemies of the German regime. Manipulating the zhydokomuna myth that linked Jews and Communists, and at the same time appealing to the racial, religious, and ethnic prejudice of local population, the Nazis branded Jews as agents of the Bolsheviks and therefore as traitors. The Nazi authorities forbade the local population under penalty of death to hide or extend any help to Jews, thus creating a legal and social barrier between them and the rest of the country's inhabitants. Hence, it is not surprising that the Nazis turned a blind eye when spontaneous pogroms against Jews broke out, such as those in Lviv (June and July 1941), the second of which came to be called the "Petlyura Days."

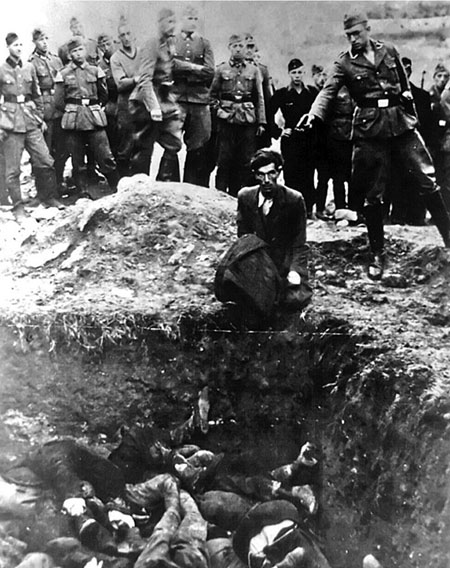

(Einsatzgruppen) executing a Jew before a mass grave near Vinnytsya in the Reichskommissariat Ukraine. Photo, 1942.

The Nazis engaged four elements in their murderous policy toward the Jewish population in Ukraine. The first of these were local police (SIPO) and secret/security police (ORPO) units, which performed a pivotal role in the extermination process. Special Operation Units (Einsatzgruppe) were the second most effective instrument of extermination, while regular German Army (Wehrmacht) troops took third place in this murderous hierarchy. Finally, there were the Ukrainian auxiliary police (Ukrainische Hilfspolizei), who were called upon to assist the German police and army units.

In dozens of localities in western and central Ukraine, the Wehrmacht selected and shot male Jews within the first days of occupation in July and August 1941. Once Jews were rounded up and physically exhausted, the Nazis — taking their cue from Stalin's dictum that the hungry neither rebel nor resist – shot them. The Nazis justified their actions as reprisals for Jewish support of the Bolsheviks or for pragmatic military reasons. The remaining Jews, predominantly the elderly, women, and children, were transferred to the newly established ghettos, usually several blocks of a town separated by barbed wire and guarded by armed police. From the very start of the German invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941, Nazi propaganda at the front was effective in convincing German soldiers and local collaborators that, regardless of age and gender, all Jewish civilians were, because of their strong association with Bolshevism, potential rebels and hence should be exterminated.

No Jew knew what was in store for him or her, since at first the Nazis introduced a sort of repressive normality in the ghettos. They ordered the establishment of Judenrats (Jewish councils), imposed taxes and contributions to extort whatever valuables from the population they could, and created the Jewish ghetto police, formally known as the Jewish Organization for the Maintenance of Public Order. Although given very little power, these Jewish bodies expedited the extortion of contributions, helped organize forced-labor battalions, supervised the liquidation of the ghettos, and guarded the remaining workers and artisans. In the end, those who staffed these bodies shared the plight of those whom they had been supervising. They were killed.

It took the Nazis more than half a year to move from killing urban Jews to the idea of the total extermination of all European Jewry. This was to include even those Jews who until then were considered crucial in providing technical support for the German Army. The police battalions moved Jews to specially allocated urban districts, from which they were soon taken to nearby woods and ravines and shot in the head one by one, or machine-gunned en masse. Among the first such cases of the Holocaust by bullets was in Kamyanets-Podilskyi, where in August 1941 German Army troops and police murdered 23,600 Jews, among whom were locals from the Podolia region as well as exiles who a few weeks before had fled to Transcarpathia but were then forcibly returned by the Hungarian authorities.

During the rest of 1941 and into January 1942, the Germans, often with the help of local police units, concentrated their murderous mission on the Jews of western and central Ukraine. Jewish residents of the largest cities in Volhynia and Podolia, together with those from the immediately surrounding rural villages, were rounded up and shot, as in Vinnytsya (15,000), Ostroh (5,500), Rivne (17,000), Proskuriv/Khmelnytskyi (7,000), and Khmilnyk (8,000). The experience in Berdychiv provided a new variant in Nazi killing procedures. Some 15,000 Jews were first moved to the Yatki ghetto. There they were left to starve, in order to suppress any thoughts of resistance. Then, during a Nazi-sponsored musical festival in the city, they were moved to a nearby airfield, machine-gunned, and thrown into a freshly dug pit. Farther to the east, despite the large-scale Soviet evacuation from major cities, the remaining Jews were left to the fate that the German occupying regime had in store for them. The most infamous case of extermination took place in Ukraine’s capital, Kyiv. The Nazi authorities issued unequivocal orders for Jews of any age or sex to gather near the old Jewish cemetery on the outskirts of the city. Cut off from any source of information and absolutely unaware of their predicament, the Jews obeyed. On the last two days of September 1941, they moved with their documents and suitcases to the assembly posts in the Lukyanivka district, expecting to be deported to Germany. Instead, they were stripped of their belongings, undressed, placed at the edge of the Babyn Yar ravine, and machine-gunned point blank. Sources record that nearly 34,000 Jews were killed in what became the first phase at the Babyn Yar killing site. Perhaps twice that number was murdered during the subsequent duration of the German occupation. The remaining Jews in other cities were also eliminated, including those in Stalino/Donetsk (20,000) and Kharkiv (12,000 at yet another infamous ravine, Drobytskyi Yar).

What took place between July 1941 and January 1942 on Soviet territory was absolutely crucial for the subsequent discussions undertaken by the Nazi leadership at the Wannsee Conference concerning the Final Solution of the Jewish Question in Europe. During the first six months after the 1941 invasion of the Soviet Union, the Nazis came to realize that they could not create the Judenfrei (free-of-Jews) territory that they had dreamed of until then. The new territories they captured had simply too many Jews to deport. Consequently, the Wehrmacht command and the Nazi authorities in Berlin decided it was preferable to exterminate the Jews on the spot. The local population was intimidated into neutrality, if not complicity, with the expectation no one would report the atrocities afterward.

Indeed, there was certain tension between the German Army and various German police battalions, although by and large the Nazis encountered few if any obstacles in implementing the executions. They quickly intimidated any local Ukrainians who tried to feed or to provide Jews with shelter. They managed to secure the complicity of the population by instigating hatred against the Jews as their immediate enemies. That the Nazis allowed local Ukrainians to plunder the liquidated ghettos made the latter personally interested in having the Jews removed. The cleansing continued throughout 1942, with 2,200 Jews murdered in Zlatopil, 6,000 in Olyka, and 14,700 in Lutsk. The last to be eliminated were Jewish forced laborers working on a strategic road connecting Germany with Ukraine: 4,000 were shot in November near Kamyanets-Podilskyi and the same number near Vinnytsya in December.

As a result, an estimated 350,000 Jews from central and eastern Ukraine alone were murdered in 1942. The accompanying Map 23 shows only a few of the estimated 1,500 murder sites in Nazi-ruled Ukraine.

Once the Nazis realized that they could exterminate eastern Europe's Jews with only a minimum number of troops and the simplest of logistical arrangements, their murderous machine was put into full gear. The proximity of the Polish-based concentration and extermination camps to western Ukraine allowed deportation from various regions of Galicia of some 530,000 Jews, who were murdered at Auschwitz, Bełżec, and Treblinka.

The fate of the Jews under the Romanian occupation was much more complex and varied depending on the territory in which they lived — Bukovina, Bessarabia, or Transnistria. Wartime Romania, under the dictatorial leadership of General Ion Antonescu, was ideologically committed to "ethnic purification." The Jews of Bukovina and Bessarabia were, in particular, slated for elimination. The Romanian government initially accepted, but then refused, Nazi Germany's plan to send the country's Jews to the death camps in Poland. Instead, Romania opted to deport its Bukovinian and Bessarabian Jews eastward to Ukraine proper. There, in Romania's newly acquired territory of Transnistria (between the Dniester and Southern Buh rivers), they would be left to die through disease and starvation. This tactic, combined with mass executions, proved to be quite successful.

Anti-Jewish persecution began in full force after Nazi Germany, in cooperation with Romanian troops, invaded the Soviet Union. During the first few weeks after the June 1941 invasion, Jews in territories taken by Romania were massacred outright (15,000 in northern Bukovina and perhaps the same number in Bessarabia). The remainder were forced into ghettos, the most prominent of which was set up in Chernivtsi in October 1941 as a transit point for Bukovina's Jews. For the next six months, they were deported, whether on foot or in railway cattle cars, to the east. By the summer of 1942, over 90,000 from Bukovina (and another 75,000 from Bessarabia) had reached Romania's newest territory, Transnistria. Ironically, perhaps as many as 20,000 Jews, mostly from Chernivtsi, were not deported, because the city's Romanian mayor (Traian Popovici) declared them "indispensable" to the urban area under his jurisdiction. This status was not, however, granted to Jews in the Bukovinian countryside, where at least 4,000 were murdered by German and Romanian troops or by Melnykite units of the OUN, which in early July 1941 provoked pogroms in an attempt to persuade the Nazi invaders to support their national cause.

As for the local Jews in Transnistria itself, an estimated 130,000 to 170,000 were killed by the new Romanian rulers, or left to die after being interned in makeshift camps. There seemed no limit to the manner of brutality, as in the case of 19,000 Jews who were burned to death in a square in Odessa within a few weeks of the city being taken by Romanian and German troops in October 1941. General Antonescu's ultimate goal was to purify Transnistria, since it was now part of "Greater Romania," by driving out all Jews, including the recently arrived deportees from Bukovina and Bessarabia who were forced northward across the Dniester River into what was then the German-controlled Reichskommissariat Ukraine. But the Germans sent them back, forcing the Romanians to set up transit camps at various places throughout Transnistria.

In effect, all of Transnistria became a zone of death for Jews. Either they were massacred (43,000–48,000 in the Bohdanivka district alone), or died from exhaustion during frequent deportations to camps, or succumbed to disease (usually typhus) and starvation in the camps. In the end, an estimated 220,000 to 260,000 Jews perished in Transnistria between 1941 and 1944. Nevertheless, about 51,000 of the deportees from Bukovina and Bessarabia managed to survive until March 1944, when the Soviet Army arrived and drove out the Romanian authorities.

During the Holocaust, the Jews of what is today Ukraine's Transcarpathian region were subjected to their new rulers, Hungary, whom many initially welcomed when the region, Subcarpathian Rus'/Carpatho-Ukraine, was annexed to Hungary in late 1938 and early 1939. They were shocked, therefore, when the Hungarian government under Regent Miklós Horthy followed the lead of his Nazi German ally and implemented anti-Jewish laws. After 1942, this meant the confiscation of lands, forests, and shops owned by Jews. As early as August 1941, an estimated 20,000 "alien" Jews who had recently fled from war-torn Poland were deported back to what was by then German-ruled territory, where most were killed at Kamyanets-Podilskyi. As for Subcarpathia's indigenous Jews, they were left in place until German forces occupied Hungary in the spring of 1944. Then, over a period of three weeks (15 May–17 June), the Hungarian authorities carried out Nazi Germany's demand and organized the deportation of virtually the entire Jewish population of Subcarpathia (116,000 as of 1944). The vast majority were killed in the gas chambers in Auschwitz-Birkenau.

Despite Nazi-inspired racist views toward ethnic Ukrainians and the suppression of Ukrainian underground forces who dared to act independently, the German authorities nevertheless engaged the collaboration of certain elements among the local population. Beginning in late 1941, ethnic Ukrainians served in the lowest levels of the local administration. They also made up a significant proportion of members in the Ukrainian auxiliary police (Ukrainische Hilfspolizei), a body which despite its name also included persons of other ethnic origin (Poles, Russians, Romanians, and Hungarians, among others).

The auxiliary police did indeed assist the Nazi German authorities in carrying out the Final Solution: rounding up Jews, bringing them to ghettos and to mass-execution sites, and providing logistical services to the Special Operations Units (Einsatzgruppe) that were assigned by the Nazi authorities to carry out the murders. From the perspective of the Jewish victims and the few survivors, such activity was inevitably associated with the Ukrainian auxiliary police and ethnic Ukrainians, regardless of the actual composition of the units and perpetrators.

As the war raged on and German forces were in retreat from eastern Ukraine, the Nazi authorities allowed for the formation of a volunteer military unit, the SS Galicia Division. Created in April 1943, the Dyviziya, as it was popularly known, was under the command of German officers and made up primarily of ethnic Ukrainians, whose primary motivation for joining was to fight alongside the German military against the Soviets on the eastern front. Victory in the east, they hoped, would result in the establishment of an independent Ukraine. While some former members of the Ukrainian auxiliary police did make their way into the ranks of the Dyviziya, for most of the unit's troops anti-Jewish feelings played a minor role, especially since they were driven more by anti-Soviet and anti-Polish attitudes that were central to the Ukrainian nationalist agenda they espoused.

With regard to the populace as a whole, there is also no question that many inhabitants in occupied lands, caught up in the wartime devastation, assisted the Ukrainian auxiliary police and benefited from the acquisition of Jewish property. On the other hand, there were numerous recorded and unrecorded cases of individuals from Ukraine of different ethnic backgrounds who tried in various ways to help save their Jewish neighbors and friends, providing them with food and shelter, warning them about the date of a ghetto liquidation, or bringing them to Soviet partisans. Aiding Jews in any way was an extremely risky enterprise, and anyone caught faced immediate arrest and deportation to a death camp.

Of the many examples that could be cited was that of the Ukrainian-American historian Taras Hunczak, who, as a young boy residing in a Galician village, served as a liaison between the Jews in the local ghetto and those who were in hiding. Then there was the Polish Broczek family in Volhynia that hid about twenty-five Jews; or Traian Popovici, the Romanian mayor of Chernivtsi, who saved upward of twenty thousand Jews from deportation; or the Ukrainian Greek Catholic priest Omelyan Kovch, who sheltered and ultimately saved six hundred Jews in Galicia. The most prominent figure engaged in such rescue efforts was the head of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church, Metropolitan Andrei Sheptytskyi, who was responsible for saving one hundred and fifty Jewish children, including the future Israeli armed forces rabbi, David Kahane. A number of Greek Catholic priests under Sheptytskyi's jurisdiction tried to save Jews by baptizing them in secret — and paid for the effort with their lives. Even some Ukrainian policemen rescued individual Jews whom they were assigned to find and execute.

With regard to the question of collaboration — massive or otherwise — on the part of the inhabitants of Ukraine with the Nazi German occupiers, it might be useful to note some comparative data. Specialists writing about the Holocaust suggest that between 1 and 2 percent of the ethnic Ukrainian population (about 28.5 million in the Soviet Ukraine and Poland on the eve of World War II) collaborated in some way with the Nazi authorities during the war. Those percentages are not much different from the situation regarding collaboration in the Netherlands, France, and other European countries, some of which were not subject to the same level of wartime destruction and brutality as Ukraine. At the same time, about 4.5 million Ukrainians fought within the ranks of the Soviet military against Nazi Germany, that is, eight to nine times more than had collaborated. Thus, one needs to use the term collaboration with great care when speaking of World War II Ukraine and ethnic Ukrainians.

The Soviet military advance into Ukraine

Most of Ukraine's inhabitants considered the Germans, Romanians, and Hungarians as foreign occupiers who should be driven out of the homeland. By 1942, partisan units were being formed in the forests of northwestern Ukraine (Polissia and Volhynia) that fought first against the retreating Soviet troops and then against the Germans. The most prominent of these groups was the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA). By the end of the war, it was dominated by the Banderite faction of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN) and it supported the political goalsâ€" a non-Soviet independent Ukraineâ€" adopted by the Ukrainian Supreme Liberation Council formed in July 1944. Also active on Ukrainian lands were Soviet partisan units which attracted to their ranks peoples of all nationalities who supported the restoration of Soviet Ukraine within the Soviet Union.

Finally, the forces of the Red Army (renamed the Soviet Army in 1944) were able to turn the tide of war following the three-month-long Battle of Stalingrad, which ended in February 1943. Thereafter, the Red Army pushed steadily across Ukraine, enabling the restoration of Soviet rule. By the end of December 1943, Ukraine east of the Dnieper River was in Soviet hands, and so was the rest of the country (including Transcarpathia) by October 1944. During those two years, whatever was left of Ukraine's industrial and agricultural infrastructure after the Soviet retreat of 1941 was largely destroyed. At the same time, millions of civilians were killed, whether the indirect result of battles between Soviet and retreating German armies, or the direct result of attacks by partisans loyal to one or another combatant: the Soviets, the Ukrainian Insurgent Army, or the nationalist Polish underground. The struggle between the UPA and Polish underground forces (the Home Army) was particularly brutal in western Ukraine, where in 1943 and 1944 both sides carried out ethnic-cleansing campaigns in the expectation that at the close of the war the historic lands of Volhynia and Galicia would be part of either a non-Soviet Ukrainian or a restored Polish state. The role that the OUN is assumed to have played in the persecution of Poles, Russians, and Jews, and the manner in which its leaders sought to balance political goals and activities on the ground in time of war, remains a source of controversy and at times friction among scholars and social commentators in Poland, Ukraine, Germany, and North America.

The post-war Soviet era, 1945–1991

By the time World War II ended in Europe on 9 May 1945 with the formal surrender of Nazi Germany, all of Ukraine was within the Soviet sphere. Territories like western Volhynia, eastern Galicia, and northern Bukovina, which were annexed by the Soviet Union in 1939–1940, were "returned" to Soviet Ukraine. Historic Subcarpathian Rus', which the victorious allies — including Stalin — promised to return to a restored pre-1938 Czechoslovakia, was instead annexed to the Soviet Union in June 1945 and allowed to be "reunified" with the Soviet Ukrainian motherland (of which it was never a part). Finally, although in entirely different circumstances, Crimea, which before and after World War II was part of Soviet Russia, was in 1954 given by Moscow allegedly as a gift to Soviet Ukraine.

Soviet Ukraine and its ethnic Ukrainians

With the return of Soviet rule and the expansion of Soviet Ukraine to the territorial extent that it has today, the centralized command economy under the direction of Communist functionaries was established throughout the country. The economic recovery was quite impressive, so that by 1955 Soviet Ukraine's industrial sector was producing 2.2 times more than it had produced in 1940, that is, before the destruction caused by World War II. The country's agricultural sector did not fare as well. The inherent inefficiency of collectivized and state-owned farms in which agricultural workers had low motivation, combined with erratic weather conditions, resulted in harvests that were below the 1940 pre-war level. At times, conditions were so bad that widespread food shortages and even famine occurred, as in 1946.

Post-war Soviet Ukraine also underwent a considerable demographic change. Aside from an overall increase in population, from 31.7 million in 1939 to 41.8 million in 1959, the settlement patterns and the relative size of the country's various nationalities changed considerably. Nearly two million mostly ethnic Ukrainians were repatriated (often forcibly) from various parts of German-controlled central Europe, while the 200,000 who were spared the return to Stalinist rule in their homeland became Displaced Persons. Most eventually emigrated to North America, while others remained in western Europe. Also, 3.8 million or so evacuees (including over 900,000 Jews), who in the face of the 1941 rapid German military advance were resettled in the east, returned home where many took up leading posts in the government and economic sector. On the other hand, certain peoples (Poles, Czechs), who in some cases had lived for centuries on Ukrainian lands, were removed as part of population exchanges with neighboring countries; others (Crimean Tatars living in what was still Russian-administered Crimea) were forcibly resettled in Soviet Central Asia; while still others had already been killed (the Jews of western and central Ukraine) or deported (Germans in steppe Ukraine) during the World War II years.

The restored Soviet regime was especially concerned with regions like Galicia, known for the deeply felt Ukrainian national sentiment of its inhabitants that dated back to pre-World War I Austrian Habsburg rule. In an effort to integrate the recently acquired western regions (Galicia, Bukovina, and Transcarpathia) with the rest of the Soviet sphere, the authorities initially concentrated their efforts in three areas. First, all businesses were nationalized and private landholdings replaced by collective farms. Second, a concerted effort was undertaken to eliminate, whether through political amnesty or armed force, the underground Ukrainian Insurgent Army, which until the early 1950s remained active in far western Ukraine. And third, the regime organized the abolition of the traditional stronghold of Ukrainian national sentiment (especially in Galicia), the Greek Catholic Church: its entire hierarchy and several hundred priests were arrested, while all remaining adherents were forced to become part of the Russian Orthodox Church. All these developments were accompanied by the resettlement of tens of thousands of Galician Ukrainians — suspected of excessive nationalist feelings — to various parts of eastern Ukraine. Finally, there was a general trend encouraged by government planners to increase the number of industrial workers. The result was a phenomenal growth of cities in Soviet Ukraine, so that by the 1970s there were five in that region, each with over a million inhabitants. About the same time another milestone was reached: Ukraine was no longer a primarily agriculturally based society, since more than half of the republic's entire population now lived in urban areas.

The most important result of these massive and relatively rapid demographic changes was a social environment in which a large portion of the country's inhabitants lost — or never really had — a first-hand sense of ancestral place. Displaced urban dwellers gave birth to a new generation of rootless offspring born and acculturated in often faceless Soviet-style modern regimented apartment blocks. Traditional cultural values, if they continued to exist at all in a Soviet system which did its best to destroy religious practices and other allegedly old-fashioned customs, survived at best in the less developed — some would say backward — rural countryside. Such developments were welcomed by the authorities, who in any case hoped to eliminate any remaining cultural remnants from the feudal and bourgeois past, riddled as they were with antiquated and superfluous religious beliefs. It certainly seemed that the time was ripe to create what came to be called the new Soviet man and woman. State ideologists even predicted — somewhat similar to Western thinkers enamoured at the very same time with theories of modernization — that nationalism was passé, and that eventually the country's various nationalities and national cultures would merge into a single new progressive and revolutionary Soviet national identity and culture.

In actual practice, Soviet became a code word for Russian, which in turn became the dominant means of communication, most especially in the Soviet Union's Slavic republics, including Ukraine. Building on tsarist russocentric traditions, the Soviet Union was quite successful in diminishing national distinctions. This was certainly the perception in the outside world, whether in Europe (Communist or non-Communist), North America, or elsewhere, where the popular assumption — reinforced by the media — was that everyone in the Soviet Union was "Russian." Many ethnic Ukrainians, especially in the east and south of the country, as well as most of the country's Jews bought into the Soviet/Russian identity and adopted Russian as their own — and in some cases their only — language.

Soviet policy toward Jews

The predicament of the Jews who survived the Holocaust and those who returned from the eastern evacuation to Ukraine during the initial post-war years was grim. Much of the reason for this was the increased Russian chauvinism and rampant antisemitism that had already begun during the last year of the war. The Moscow-based Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee, which had done a formidable job mobilizing the U.S.-sponsored Lend-Lease program during World War II and winning world support for the Soviet Union, now proposed that the Soviet government acknowledge the exceptional suffering and losses of the Jewish people during the war, that it recognize that Jews had lost their homes, and that it establish an autonomous district for them in Crimea.

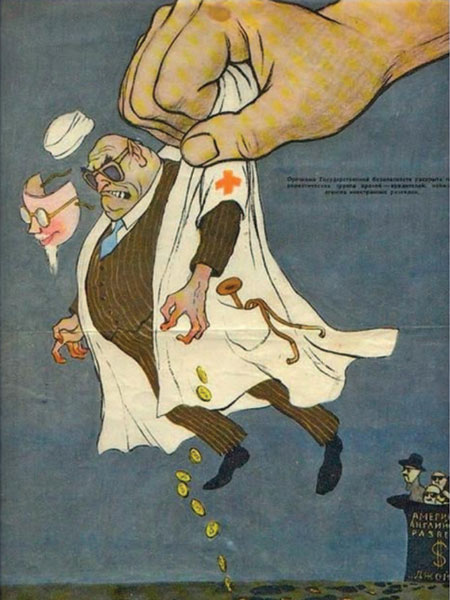

The Kremlin leadership and the security organs considered these requests as nothing less than an affront. It responded that the Soviet people had all suffered as one entity, so that acknowledging a unique Jewish plight would be tantamount to a claim based on national specificity. Consequently, Jews returning from the eastern evacuation or from the Nazi German camps were left to deal one-on-one with the Soviet bureaucracy and with peoples who had taken over their homes. In an atmosphere characterized by mounting Cold War tensions, members of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee were suspected by state security organs as being spies for the new enemy — the capitalist West. It is in such a context that the regime forbade the publication of The Black Book, the first collection of documents about the Nazi atrocities that was prepared for publication by the Berdychiv-born Vasilii Grossman and the Kyiv-born Ilya Ehrenburg. Any mention of the exceptional status of the Jews as the foremost targets of the Nazis had to be obliterated.

The Soviet censors moved to cross out any mention of Jews in their reports of Nazi atrocities. Instead, they were referred to by a vague formulation — "peaceful Soviet citizens." In response to the rising pride of the Jews, who were third in number of awardees among wartime Heroes of the Soviet Union in the defeat of the Nazis, the Kremlin unleashed vicious antisemitic campaigns against Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee members (many of whom were Yiddish-speaking writers and poets from Ukraine), against Jewish cultural elites, and finally against Jewish doctors. In 1948–1953 dozens of Jewish authors, scholars, and public figures found themselves behind bars. The Yiddish-language literati Nosn Zabara, Moyshe Pinchevskyi, and Gershl Poliakner, all members of the Union of Writers of Ukraine, were imprisoned. The Research Center of Jewish Culture at the Ukrainian Academy of Sciences was closed and its director, the renowned literary critic and linguist Elye Spivak, tortured to death by the state security.

In the wake of the creation of the state of Israel and the enthusiastic popular support it garnered among ordinary Jews throughout the Soviet Union, the Jews could no longer be considered a loyal minority. They now became in the eyes of the regime a diaspora nationality of bourgeois nationalist traitors, a kind of Cold War fifth column. On 12 August 1952, after a four-year unsuccessful trial during which members of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee refused to incriminate themselves, several Yiddish celebrities, including some from Ukraine — Itsik Fefer, Dovid Bergelson, Perets Markish, and Leyb Kvitko — were secretly executed. This was a tragedy of such significance that Workmen's Circle Unions throughout the United States continue to commemorate it annually to this day. In effect, between 1948 and 1953, the Soviet regime used all means of propaganda possible to vilify Jews as bourgeois nationalists. Stalin's death in March 1953 put an end to a five-year-long campaign of state-orchestrated antisemitism, even though its ramifications were still palpable decades later.

During the immediate post-war years and through the 1950s, observant Jews made several attempts to revive religious life and reestablish traditional communities. Following Soviet guidelines, they organized so-called dvatsyadky, groups of minimally twenty people each that allegedly would be allowed to establish prayer groups. In fact, Soviet security organs allowed such groups only if they included one or more informants (moles) who could supervise membership, attendance, and the spirit and tenor of the conversations. The authorities did allow a maximum of one synagogue or prayer group per town, while at the same time doggedly persecuting any attempts to organize non-sanctioned prayer groups (minyonim). Despite the close surveillance and regular denunciations by secret police informants, the synagogues, beginning in the 1950s and continuing until the early 1980s, went from being the semi-legal foci of traditional Jewish life to information centers on Jewish genealogy and emigration. Nevertheless, the regime prohibited members of the older generation from engaging youth, penalized those who disobeyed, and arrested anyone trying to take prayer books out of the synagogue for teaching purposes. In particular, clandestine teachers of Hebrew were incarcerated, since they were considered to be guilty of promoting a bourgeois, nationalist language couched in religious propaganda.

Ukrainian dissidents and Jewish intellectuals

The so-called Thaw of the late 1950s and early 1960s, a period when the Soviet leadership reduced to a degree the strict government controls and censorship that characterized Stalinist rule, also witnessed an unprecedented rapprochement between the country's leading Ukrainian and Jewish intellectuals. They were united in their rejection of state-orchestrated policies of enforced assimilation, de-Ukrainianzation, and antisemitism. For example, Vasilii Grossman finished an epic novel, Life and Fate, and a historical short novel, Forever Flowing, works in which he not only equated Stalinism and Nazism but also traced parallels between Ukraine's Great Famine (Holodomor) and the Holocaust and the victimization of Ukrainians and Jews. In 1966 Ukrainian writers and civic activists Ivan Dzyuba, Viktor Nekrasov, and Borys Antonenko-Davydovych joined Kyiv's Jews in commemorating the twenty-fifth anniversary of the massacre at Babyn Yar. It was Dzyuba's speech at this event that marked a turning point in Ukrainian-Jewish relations.

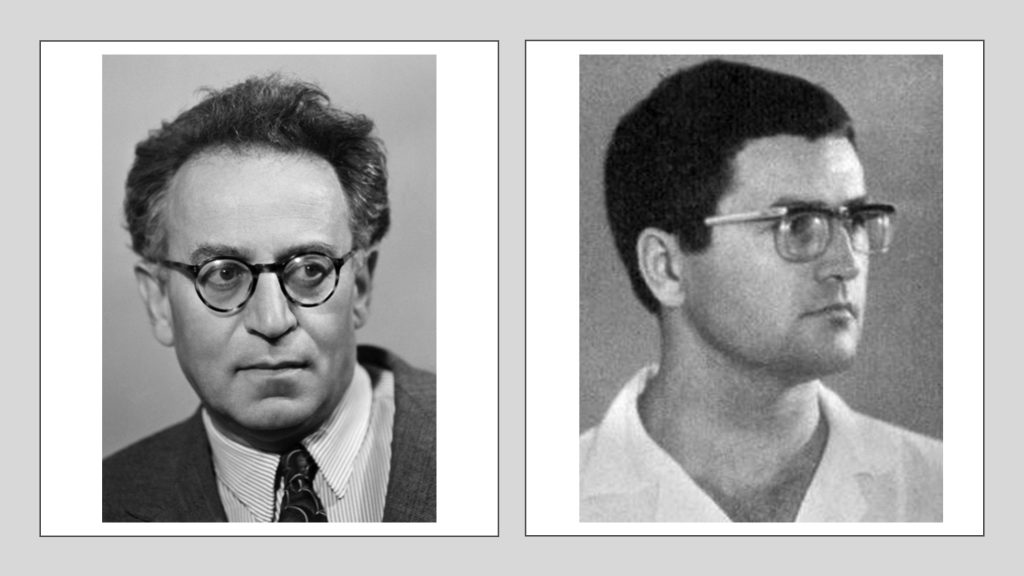

Close relations between Jewish and Ukrainian intellectuals continued even after the Soviet regime under Leonid Brezhnev ended the short-lived liberal atmosphere of the Thaw and, beginning in the mid-1960s, reinstituted repressive measures against critics of the regime who came to be known as dissidents. It was on behalf of one of the Soviet Union's leading dissidents at the time, the ethnic Ukrainian and decorated World War II veteran Petro Hryhorenko (Petr Grigorenko), that a Jewish psychiatrist from Ukraine, Semen Gluzman, submitted an expert report attesting to the mental health of the former Soviet army general whom the regime was trying to portray as insane. Many of the encounters between ethnic Ukrainian and Jewish liberal and national-minded individuals actually took place in Soviet correction colonies during the Brezhnev eraâ€" an environment that ironically fostered a new and positive understanding of Ukrainian-Jewish relations. It was precisely these intellectuals who in the late 1980s united in the Popular Movement of Ukraine for Restructuring. Best known by its Ukrainian name, Rukh (the Movement), it was instrumental in creating a new atmosphere of tolerance and mutual respect among ethnic Ukrainians and Jews on the eve of and after the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Gorbachev era and the road to Ukraine's independence

The stagnant economic and repressive political policies of the Soviet system prompted the need for changeâ€" and such change finally began in 1985. In that year, a relatively young party functionary, Mikhail Gorbachev, became head of the All-Union Communist party and, eventually, the most influential figure behind a program of reform known as perestroika (restructuring of society) and glasnost (openness to change dependent upon civic participation). Reform came much more slowly to many peripheral regions of the Soviet Union, including Soviet Ukraine. When, however, it did finally begin there in 1989, national patriots who had remained silent before (or who had been part of the Communist system) joined a series of organizations that were determined to raise the prestige of Ukrainian culture and language and to transform the Soviet Union into a true federation of equal republics.

The leading force for national and democratic change was Rukh. Because of a change in the electoral law, which allowed parties other than the Communists to field electoral candidates, Rukh managed in early 1990 to enter Soviet Ukraine's parliament (Verkhovna Rada) as part of a Democratic Bloc. The Rukh activists were joined by a number of Communist deputies who hoped to remain in power by adapting to the current nationalist fervor. Together they were able to push through parliament the declaration of Ukraine as a sovereign state in July 1990.

After almost a year of debate and negotiations regarding the future relationship of the now sovereign Soviet Ukraine to the rest of the Soviet Union, the situation came to a head in the late summer of 1991. In August, Communist political conservatives attempted to carry out a coup in Moscow; their failure after just three days prompted the parliament in Kyiv to declare, on 24 August 1991, Ukraine an independent democratic state. To gauge and, it was hoped, gain the support of the population at large, a state-wide referendum was held on 1 December 1991. A remarkable 92 percent of Ukraine's population — people of all ethno-national backgrounds — voted for independence. Almost as an afterthought, at the end of month, on 31 December 1991, the Soviet Union ceased to exist. Ukraine had now entered the community of Europe's independent states.

Click here for a pdf of the entire book.