Chapter 3: "Jews and Ukrainians: A Millennium of Co-Existence"

Jews and Ukrainians: A Millennium of Co-Existence is an award-winning book that explores the relationship between two of Ukraine’s most historically significant peoples over the centuries.

In its second edition, the book tells the story of Ukrainians and Jews in twelve thematic chapters. Among the themes discussed are geography, history, economic life, traditional culture, religion, language and publications, literature and theater, architecture and art, music, the diaspora, and contemporary Ukraine before Russia’s criminal invasion of the country in 2022.

The book addresses many of the distorted stereotypes, misperceptions, and biases that Ukrainians and Jews have had of each other and sheds new light on highly controversial moments of Ukrainian-Jewish relations. It argues that the historical experience in Ukraine not only divided ethnic Ukrainians and Jews but also brought them together.

The narrative is enhanced by 335 full-color illustrations, 29 maps, and several text inserts that explain specific phenomena or address controversial issues.

The volume is co-authored by Paul Robert Magocsi, Chair of Ukrainian Studies at the University of Toronto, and Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern, Crown Family Professor of Jewish Studies and Professor of History at Northwestern University. The Ukrainian Jewish Encounter sponsored the publication with the support of the Government of Canada.

In keeping with a long literary tradition, UJE will serialize Jews and Ukrainians: A Millennium of Co-Existence over the next several months. Each week, we will present a segment from the book, hoping that readers will learn more about the fascinating land of Ukraine and how ethnic Ukrainians co-existed with their Jewish neighbors. We believe this knowledge will help counter false narratives about Ukraine, fueled by Russian propaganda, that are still too prevalent globally today.

Chapter 3

Economic Life

There is a popular assumption that ethnic Ukrainians have throughout history been primarily rural-dwelling agriculturalists. To a large extent that assumption is borne out by reality, at least until the twentieth century. It is certainly true that a favorable climate and rich soils covering most of Ukraine have made the country an ideal setting for growing a wide variety of crops, whether for human consumption, for livestock feed, or for industrial use. Not unexpectedly, the vast majority of inhabitants on the territory of present-day Ukraine have been farmers, beginning with the first sedentary peoples connected with the Trypillian culture of the Neolithic period and lasting several millennia (4500–2000) before the Common Era, then with the various Slavic tribes during the centuries before Kievan Rus' and continuing with the direct ancestors of today's ethnic Ukrainians during the era of Lithuanian, Polish, Muscovite, Russian, and Austro-Hungarian rule.

Agriculture

Ethnic Ukrainians

Aside from planting and harvesting crops, almost without exception each homestead had at least one cow from which dairy products were derived in order to sustain life. In that sense, the family cow was essential for one's existence and equally as important as the amount of arable land that one tilled. Only in far western Ukraine, in the foothills and upper slopes of the Carpathian Mountains, did some rural dwellers gain their livelihood from animal husbandry (mainly sheep) or from forest-related work (as wood-cutters and haulers).

The legal status of ethnic Ukrainian agriculturalists evolved over the centuries — and mostly for the worse. In Kievan times, most were "free persons," but during Polish-Lithuanian rule they became increasingly dependent on noble landowners to whom they paid dues (in labor and kind) until in the late sixteenth century they became proprietary serfs attached to the land.

Most ethnic Ukrainians remained agriculturalists, as proprietary serfs or state peasants, regardless of the state that succeeded Polish-Lithuanian rule in Ukraine: the Tsardom of Muscovy, the Russian Empire, or the Austrian Empire. Even after the emancipation from serfdom (1848 in the Austrian Empire and 1861 in the Russian Empire), many of Ukraine's peasant agriculturalists became what might be called "economic serfs," that is, "free" persons indebted to their former landlords or moneylenders — and often on a permanent basis. There were, however, some enterprising peasant farmers in both the Austrian and Russian empires who were able to break the cycle of debt, expand their landholdings, and turn a profit from the crops they harvested (often by employing fellow indebted peasants).

In the first half of the twentieth century, the status of Ukraine's agriculturalists changed radically. In western Ukrainian lands ruled by Poland, Romania, and Czechoslovakia, farmers survived (some even flourished) by joining voluntarily agricultural cooperatives in which they had some say over how the fruit of their labor was marketed and sold. In eastern Ukraine under the Soviet Communist rule, collectivization — at first voluntary but after 1929 forced — brought an end to private land ownership. Consequently, farmers in many ways became similar to industrial workers, their "industrial sites" being village-based collective farms (kolhospy) or huge state-owned farms (radhospy). The socialist agricultural worker was no longer a farmer, whose generations of experience helped decide what crops to grow and how, but rather an employee working for the village collective or the state, which paid its employees a wage or more often in kind. The payment in kind, determined by labor units (number of hours worked or the amount of harvest), was hardly enough to allow a family to survive.

Despite the changing and often unenviable legal status of agriculturalists over the centuries, at the same time ethnic Ukrainians developed a profound love for the land and the crops that it could produce, if properly managed. Sheaves of wheat, for example, became — and remain to this day — a graphic symbol or branding for Ukraine as a country. And, as a corollary, many ethnic Ukrainians came to believe in a kind of moral superiority of those who worked the land, in contrast to others in society who "exploited" it for their own personal gain, whether the exploiter be a noble landlord, a "foreign" urban dweller, or a dictatorial state.

Despite the changing and often unenviable legal status of agriculturalists over the centuries, at the same time ethnic Ukrainians developed a profound love for the land and the crops that it could produce, if properly managed. Sheaves of wheat, for example, became — and remain to this day — a graphic symbol or branding for Ukraine as a country. And, as a corollary, many ethnic Ukrainians came to believe in a kind of moral superiority of those who worked the land, in contrast to others in society who "exploited" it for their own personal gain, whether the exploiter be a noble landlord, a "foreign" urban dweller, or a dictatorial state.

Jews

For centuries, Jews were the major mediators between rural and the urban areas in their role as traders in agricultural products. Until the late eighteenth century, most Jews were engaged in various kinds of trade, particularly in grain, cattle, and lumber. The Russian authorities at the time, however, deemed trade a non-productive occupation and, therefore, made several efforts to resettle Jews on the land.

Although Jews were promised tax exemptions (for long periods of time), only a few thousand took up the offer and became farmers. Their reluctance was in part due to the inefficient and corrupt administration of the state-sponsored agricultural colonies. Despite such impediments, in the 1850s and 1860s Jewish agricultural settlements gradually increased, especially in southeastern Ukraine, so that in Kherson province by the end of tsarist rule in 1917 about 42,000 Jews lived and worked as farmers in thirty-eight agricultural colonies. The last decades of the nineteenth century were also a time when groups of Kharkiv and Odessa university students known as BILU (acronym of the biblical verse "Come, sons of Jacob, let us go," Isaiah 2: 5) left the empire to establish agricultural settlements in the land of Israel. These eventually became known as kibbutzim (communal agricultural colonies similar to Russia's agricultural communes), which later attracted thousands of eastern European Jews and became the economic beacon for Israeli agriculture.

Unlike the Jews in the Russian Empire, those living under Austrian Habsburg rule were, from the 1770s, not only allowed to be farmers but also (after 1867) to own land. More than 13 percent of Galicia's Jews worked in some aspects of the agricultural sector, whether as farmers working the land, as dealers in agricultural products, or in property management. Actually, 50 percent of all Galician farm and estate leaseholders were Jews. And, of the province's forty-five large landowners who possessed more than 15,000 acres of land, six were Jews. Jews were especially successful in the cattle and poultry trade. In Austrian Bukovina, Jews were also active in agriculture, whether in trading or in transporting agricultural produce, much of which came from the province's largest estates which happened to be owned by Jews as well.

Ever since the beginning of the Zionist movement in the last decades of the nineteenth century, its ideologists tried to convince Jews in both the Russian and Austro-Hungarian empires to take up "productive labor," that is, to work the land as farmers and preferably to do so after emigrating to the historic land of their forefathers — Israel. Zionist goals were never achieved before World War I. Following the collapse of the Russian Empire in 1917 and its eventual replacement by a state under Bolshevik rule, the new Soviet authorities adopted their own policy toward Jews. Like the Zionists, the Soviets also set out to engage Jews in productive labor and, therefore, launched a colonization experiment in the 1920s. It was sponsored not only by the central government-controlled Committee for the Settlement of Jewish Laborers on the Land (KOMZET) but also by the Agricultural Corporation (Agro-Joint) of the American Joint Distribution Committee (the Joint). On the plains of southern Ukraine between Zaporizhzhya and Kherson as well as in northern Crimea, about thirty highly successful Jewish agricultural cooperatives were established (see map 20). There, more than one hundred thousand Jews worked as farmers between 1924 and 1938. These collective farms, in stark contrast to the failed colonizing project in Birobidzhan Autonomous District near the far eastern Soviet-Chinese border, embodied the success of Soviet Ukraine's agricultural initiative. Ukraine's Jewish collective farms, built around the renewal of the Yiddish language and proletarian ideology, were given ideologically inspired names, such as Fraidorf, Kalinindorf, Lenindorf, and Yudendorf — literally: The Free Village, Kalinin Village, Lenin Village, and Jewish Village. The joy felt by Jews who left the traditional and moribund shtetl to work the land like a Ukrainian peasant was best depicted in plays by Peretz Markish (Nit gedaiget!/Don't Worry) and Leonid Pervomaiskyi (Mistechko Ladenyu/The Shtetl Ladeniu), which were performed in many Ukrainian theatres during the 1930s.

Urban merchants, artisans, and laborers

Medieval Kievan Rus', described in contemporary Scandinavian sources as "the land of fortified towns" (Gardariki), was known for the high proportion of urban dwellers in comparison to the rest of Europe. The Rus' ancestors of modern-day ethnic Ukrainians most likely accounted for the largest proportion of townspeople (lyudy hradski), who made their living as merchants, artisans, and unskilled laborers and servants. No less than sixty different handicrafts in the building, transport, clothing, food preparation, and arms trades were known to have existed among medieval Rus' urban artisans. In subsequent centuries, the proportion of Ukraine's urban dwellers who were ethnic Ukrainians declined, largely because of the influx of foreign immigrants (Germans, Jews, Armenians, Greeks) reputed for certain skills and because of legal restrictions and discrimination. For example, in Ukrainian lands ruled by Poland-Lithuania, non-Catholic townspeople (Orthodox Ukrainians, Jews, Armenians) were deprived of membership in professional guilds and city councils.

Despite the various forms of legal and social discrimination, Orthodox Rus’-Ukrainian townspeople managed to maintain their economic status and even organized pre-modern businessmen's associations, the so-called confraternities or brotherhoods, which funded hospices, cultural activity (especially schools and book printing), and the building and functioning of Orthodox churches — all in an effort to defend the language and religious culture of their people. The philanthropic and cultural nature of the brotherhoods confidently disguised their other purpose: trade and business pursuits, which allowed Orthodox Rus’-Ukrainians to compete with the privileged guilds reserved for Catholic urban artisans. In eastern Ukraine, during the late seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, ethnic Ukrainians remained the dominant element in towns and cities and, as such, contributed heavily to the economic well-being, cultural achievements, and military ventures of the Cossack state within the framework of the Tsardom of Muscovy and later Russian Empire.

In contrast to the restrictions on Orthodox Rus’-Ukrainian urban dwellers in Poland-Lithuania, Jews were welcomed by the authorities as the perfect agents of urbanization. In order to transform a low-income village into an economically advantageous town, the Polish landlord needed to obtain a privilegia (concession) from the king or the government. Such concessions allowed for the establishment of regular trade, annual fairs, and a monopoly on liquor production (propinacja) in a particular locality. As a result, in Poland-Lithuania trade and liquor production were economic activities that relied entirely on the Jews and required their permanent residence. Polish landlords by and large did not want to engage in what they considered a dirty business; hence, they leased these two key functions — trade and the production of alcohol — to the Jews. Thus, the evolution of small rural settlements into important early modern market towns in the Volhynia (Berdychiv, Dubno, Korets, Ostroh), Podolia (Medzhybizh, Tulchyn), and Kiev provinces (Bila Tserkva, Skvyra, Uman) depended to a great extent on the economic role played by Jews.

Not surprisingly, Jews dominated the marketplace, where they represented on average over 90 percent of all traders. Later, in the 1790s, when the Russian Empire annexed Poland's Ukrainian-inhabited lands, the tsarist regime permitted Jews membership in trade guilds and in the elitist social estate of merchants. It was not long before they came to represent from 85 to 90 percent of all third- and second-guild merchants. First-guild merchants, meanwhile, were usually Christian wholesale monopolists.

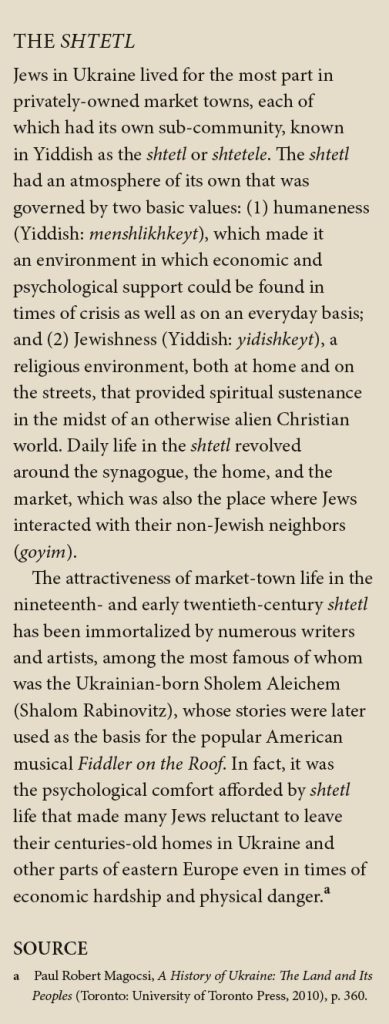

Already during Polish rule, Jews settled near the marketplace in urban quarters known as shtetls (Yid.: shtetlekh), where they built dwellings that usually included a shop and an inn as well as their personal residence. Most, if not all, trading stalls (torhovi ryady) in the marketplace of Ukrainian towns before the mid-nineteenth century belonged to Jews. As a rule, Jews competed among themselves and not with the Christian first-guild monopolists, who relied on governmental commissions and saw little competition. In practice, Jewish success in trade depended on low revenues and rapid turnover, not on their relations with the regime in power.

The Jews were multi-taskers. Male and female Jewish merchants dealt simultaneously in textiles (various fabrics as well as yarn and thread), finished haberdashery items (kerchiefs, gloves, stockings, socks), delicacies (caviar, sugar, coffee, tea, chocolate, dates, figs, etc.), leather goods (boots and belts), accessories (earrings and hairpins), luxury items (snuff boxes and smoking pipes), and — most important of all — basic food staples (salt and fish). As a result of Polish concessions (privilegia) and the possibility to travel, combined with their knowledge of the market and their all-important family connections, Jews came to dominate international trade during the period of Polish rule in Ukraine. Their trade networks brought goods from the Ottoman Empire to the south, from Muscovy/Russia to the east, and from European lands (Swabia, Prussia, Provence) to the west. After the disappearance of Poland-Lithuania in 1795, trade from Russian-ruled Volhynia and other tsarist provinces in Ukraine reached neighboring Austrian-ruled Galicia through Jewish hands. Even when tsarist authorities decided to impose rigorous customs tariffs for political and economic reasons, Jewish merchants (often with help of Polish, Muscovite, and Ukrainian Cossack officials) transformed legal trade into cross-border contraband.

The Jews were multi-taskers. Male and female Jewish merchants dealt simultaneously in textiles (various fabrics as well as yarn and thread), finished haberdashery items (kerchiefs, gloves, stockings, socks), delicacies (caviar, sugar, coffee, tea, chocolate, dates, figs, etc.), leather goods (boots and belts), accessories (earrings and hairpins), luxury items (snuff boxes and smoking pipes), and — most important of all — basic food staples (salt and fish). As a result of Polish concessions (privilegia) and the possibility to travel, combined with their knowledge of the market and their all-important family connections, Jews came to dominate international trade during the period of Polish rule in Ukraine. Their trade networks brought goods from the Ottoman Empire to the south, from Muscovy/Russia to the east, and from European lands (Swabia, Prussia, Provence) to the west. After the disappearance of Poland-Lithuania in 1795, trade from Russian-ruled Volhynia and other tsarist provinces in Ukraine reached neighboring Austrian-ruled Galicia through Jewish hands. Even when tsarist authorities decided to impose rigorous customs tariffs for political and economic reasons, Jewish merchants (often with help of Polish, Muscovite, and Ukrainian Cossack officials) transformed legal trade into cross-border contraband.

Because in Muscovy and the later Russian Empire Jews were not allowed to own land, whatever economic activity they engaged in took the form of leases from private landlords or the government. They usually paid up-front, after which they were allowed to lease mills, taverns, distilleries, fish ponds, forests and the lumber trade, customs, postal services, weights and measures, marketplace trading stalls, tax collecting, and all sorts of arts and crafts. Jews as leaseholders (orendari) were responsible for the entire economic infrastructure of Ukraine's urban centers from the sixteenth to nineteenth centuries. Regardless of pre-partition Polish-Lithuanian or subsequent imperial Russian rule, the economic situation changed little, since most towns remained under private ownership at least until 1830 and even until the 1860s. Although they were privileged leaseholders, Jews had to pay a high price for this dubious privilege. Their landlords imposed exorbitant taxes and duties, so that Jewish leaseholders themselves could hardly make both ends meet. At the same time, the ethnic Ukrainian peasants and other Christian inhabitants considered all orendars to be bloodsuckers. Some of the richest Jews, the heads of the mercantile elite, were responsible for collecting duties and taxes and were often serving as the leaseholders of the towns or villages. Their economic self-interest triggered multiple social and moral conflicts within the much more frugal Christian and even Jewish communities.

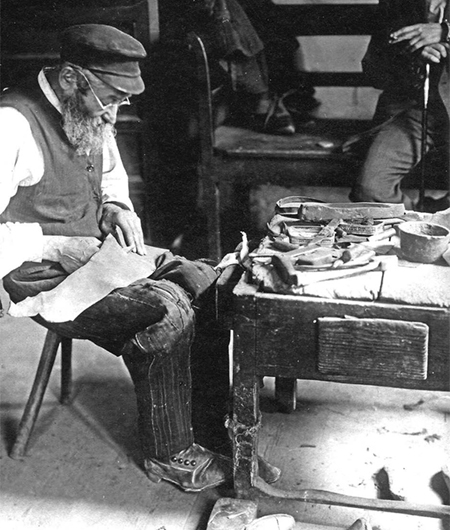

After the merchants, leaseholders, and tavern-keepers, the fourth most important group of economically active Jews were the artisans. Although disliked by merchants at all levels, including poor peddlers, Jewish artisans became a respected and very visible part of society by the end of the nineteenth century. In fact, Jews comprised in many towns the overwhelming majority of artisans — millers, blacksmiths, silversmiths, watchmakers, tailors, shoemakers, milliners, closet-makers, wagon-makers, wheel-makers, tanners, saddlers, carpenters, masons, bakers, and butchers — and accounted by the end of the nineteenth century for 60 percent of all working Jews. Jewish artisanal pride became proverbial. In a famous joke, one Jew asks another: Where did you have your lapserdak (jacket) tailored? In Paris. Is that far from Berdychiv? Yes, very far. Incredible! Such a faraway province yet so well-tailored!

Although Jews were not allowed to enroll in Christian craft guilds, they often created their own professional societies called havurot, which were disguised as voluntary religious confraternities. These professional confraternities performed functions characteristic of Orthodox Christian confraternities (brotherhoods): they brought together skillful professionals of a certain craft; restricted access to those able to pay the entry fee; established fixed prices on services and products; extended social relief to needy members; provided free start-up loans; and sent their members to visit the sick and bury the dead. Towns such as Lutsk in Volhynia had several major havurot of tailors and shoemakers by the mid-eighteenth century, while Berdychiv and Baranivka in Podolia had dozens of havurot a century later that brought together artisans of various professions, including bricklayers, carpenters, and even coffin-carriers. Some of the artisan confraternities grew to be so influential that they preferred to split off from the elitist communal oligarchy, the kahal. On their own, they raised funds, commissioned Torah scrolls, and established synagogues (Yiddish: shul).

Industrialization

In the course of the nineteenth century, eastern Ukraine experienced the beginnings of industrial development. The trend continued steadily, so that by 1900 the region accounted for one-fifth of all factory manufacturing output in the Russian Empire. It is true that the most of the workers in these new industries were not ethnic Ukrainians, who, if they wanted to improve their economic status, tended to migrate eastward to farmlands in southern Siberia.

Industrialists in Russia and Austria-Hungary

On the other hand, some ethnic Ukrainians (known at the time as malorosy/Little Russians) were among the country's leading business people. As early as 1832, 29 percent of all factory proprietors were ethnic Ukrainians/Little Russians (compared to 17 percent owned by Jews), while among townspeople who owned industrial firms, 31 percent were ethnic Ukrainians (compared to 12 percent owned by Jews). Among the most prominent ethnic Ukrainian industrialists in the Russian Empire were three family dynasties, the Tereshchenkos, Yakhnenkos, and Symyrenkos, who made their enormous fortunes in the sugar-refining industry. While most of these and other industrialists and townspeople adapted to the Russian or Austrian imperial environment in which they functioned, often taking on a Russian or Polish (in the case of Austrian-ruled Galicia) identity, there were some who contributed to the Ukrainian national movement, whether through financial support or civic work. Among such figures were Platon Symyrenko, who funded the most famous work in Ukrainian literature (Taras Shevchenko's Kobzar), and the descendant of burghers from Poltava, Symon Petlyura, who later played a leading role in the post-World War I Ukrainian revolutionary era.

On a much larger scale were the Jews, who were pivotal in the early stages of Ukraine's industrialization. Although initially most of the factories producing brick, copper, and saltpeter were owned by Polish magnates, such as the Czartoryskis, Potockis, and Sanguszkos, it was the Jews who leased, operated, and further developed these enterprises. At the very outset of the nineteenth century, these included a whole host of Jewish-operated enterprises throughout Volhynia and Podolia.

Jews were no less visible in industry and trade in nineteenth-century Austrian-ruled Galicia and Bukovina. There, too, they engaged in artisan occupations organized around confraternities and they owned breweries and tanneries and leased taverns and sawmills. They were particularly active in cement and petroleum production in Galicia, while in Bukovina they were widespread as clerks in banks and credit firms. By the late nineteenth century, however, the Austrian authorities, supported by Galician-Polish landowners and wholesale merchants, introduced a number of regulations that made Jews redundant in several of the economic sectors which they had controlled for centuries. For example, Jews were forbidden to trade in alcoholic beverages, and merchants were forbidden to trade on Sundays. Since most Jewish merchants were observant and did not do business on the Sabbath (Saturday), this regulation created an additional obligatory day off which had a seriously negative impact on profits.

Such drawbacks were nonetheless mild in comparison with the rapid deterioration and financial ruin of the lower classes of the Jewish population, for example, the working proletariat involved in Galicia's petroleum industry. Crude oil had been found in the Drohobych region of East Galicia, especially around Boryslav, in the early 1800s. Several Jewish amateur experimenters and pharmacists attempted to distill oil and use it for lighting and to produce wax (a by-product for lubrication), but only in the last third of the nineteenth century were industrial-size refineries established. Blue-collar Jews worked alongside ethnic Ukrainians and other Christian peasants. By 1900, there were more than fifty refineries producing 4 percent of the world's refined oil. The international cartels aggressively moved in to exploit these resources, with the result that the new managers laid off the Jews and hired much cheaper and less class-conscious Christian peasant laborers instead. The terrible sanitary conditions, the exploitation of workers, the general impoverishment of the local population, some of whom where of Jewish descent, were portrayed by the Ukrainian writer Ivan Franko in his famous novel, Boryslav smiyetsya (Boryslav Is Laughing, 1881).

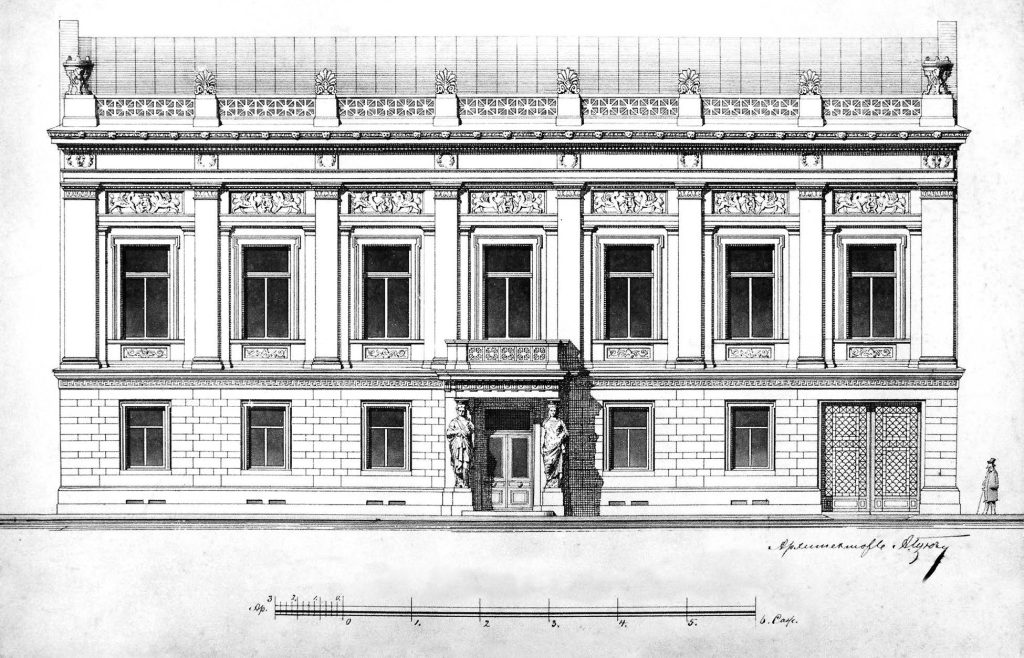

While most Jews on the both sides of the Austrian-Russian border lived in relative poverty, there were also some very rich individuals, particularly in the Russian Empire. By the second half of the nineteenth century, a new generation of Jewish entrepreneurs (liquor-trade monopolists, bankers, factory owners) played a major role in the development of the Russian Empire's industrial sector in Ukraine. Lazar and Lev Brodsky continued the work of their father and invested in the creation of Ukrainian beet-sugar refineries, which produced more than 25 percent of all sugar in pre-1917 Russia. The Brodskys also sponsored major philanthropic projects in Kyiv, including the Bessarabian Market and the Polytechnic Institute, as well as the choral synagogues in Kyiv and Odessa. Another millionaire and contractor in Kyiv, Lev Gintsburg, built famous city edifices which today function as the Philharmonic Society, the Teachers' Club, the National Central Bank, the National Ukrainian Museum, and the first twelve-storey skyscraper in the Russian Empire on Khreshchatyk Street (the Gintsburg House destroyed in 1941). The Karaite Solomon Kogan invested in the development of successful tobacco businesses throughout Ukraine, while the Poliakov brothers established the Industrial Bank in Kyiv and the Society of South-Russian Coal Mining Industry.

The rapid industrialization of imperial Russia in the late nineteenth century also had a downside for Jews. Many traditional Jewish craftsmen became unemployed, since they could not compete with the production of the modern textile or footwear industries, let alone the agricultural tools produced by newly established machine-building factories. Increasingly impoverished, Jewish craftsmen became part of Ukraine's proletariat in big cities such as Kharkiv, Katerynoslav, Zhytomyr, Odessa, and Kyiv, where many eventually sought social justice by joining various revolutionary cells.

Entrepreneurs in Soviet and independent Ukraine

The establishment of Soviet rule in the twentieth century, first in eastern Ukraine (ca. 1920) and then in western Ukraine (after 1945), profoundly changed the status of all peoples living in the country. As for ethnic Ukrainians, they increasingly moved to urban areas, so that, whereas in 1920 they comprised 32 percent of the inhabitants in towns and cities, by 1989 that figure had increased to 60 percent. There they were employed as factory workers, miners, and managerial staff in the Soviet state-directed command economy. Concentrated in regions around cities like Dnipropetrovsk, Zaporizhzhya, Donetsk, and Kyiv, many of the large state-owned industrial complexes were directed by local ethnic Ukrainians, who had risen through the managerial ranks. For example, independent Ukraine's second president, Leonid Kuchma, was already a figure of enormous power and influence as director of one of the world's largest industrial complexes based in Dnipropetrovsk for the manufacture of rockets, satellites, and conventional arms.

The tradition of ethnic Ukrainians as large-scale industrialists has continued in post-Soviet independent Ukraine, where changing economic and political conditions have allowed some businesspersons to amass enormous wealth, such as Dmytro Firtash (gas and electricity distribution), Oleh Bakhmatyuk (agricultural commodities), Serhii Taruta (metallurgy and coal extraction), Yuliya Tymoshenko (gas and oil distribution), and Petro Poroshenko (confectionary production). Meanwhile, by the outset of the twenty-first century, employment patterns were radically different from what they had been a century before. The country's overall work force (52 percent) now earned its livelihood in jobs related to the urban-based industrial sector (manufacturing, mining, construction, transport, various commercial and retail services), while only 17 percent were engaged in agriculture and forestry work. Ukraine as a whole — and its ethnic Ukrainian inhabitants in particular — no longer fits the stereotype of a country of rural peasant farmers. That is an image from the far distant past.

In the wake of the Bolshevik Revolution in late 1917, the new Soviet authorities frowned on traditional Jewish occupations such as trade, and they were in particular opposed to independent artisan work. Such work was conducive, so they thought, to the religious and bourgeois ideological worldview, something that the Soviets wanted at all costs to eradicate. Nonetheless, during the New Economic Policy (NEP) which characterized much of the 1920s, the regime allowed a degree of private ownership. As a result, Jews managed to re-establish a network of restaurants and cafeterias, bars and taverns, confectionaries and bakeries, and a wide range of artisan shops throughout the larger cities of Soviet Ukraine. Many Jews even organized groups of kustari, manufacturers who had their own independent small-scale factories producing everything from hats and coats to furniture. After 1928, however, the introduction of the state-directed command economy led to a ban on private businesses, with the result that many Jewish NEP-men became lishentsy, socially redundant petty bourgeois who were declared enemies of socialism and the future Communist order.

Nevertheless, many enterprising Jews were able to adapt to the ideological demands of Stalin's command economy and, by 1930s, to take up positions as directors and managers in state-owned industrial factories both large and small. Following World War II, and with the rise of antisemitic tendencies in Soviet society, many Jews were removed from leading positions in Soviet Ukraine's industry and commerce, a trend that continued through the 1950s and 1960s. Some responded by "moving underground"; they engaged in clandestine production and traded in goods otherwise absent from stores owing to the cumbersome, inefficient, and customer-unfriendly socialist economy. Since the regime deemed private economic initiative a threat to the state-directed command economy and to socialist ideology in general, many of these economically underground Jewish business people were arrested, tried, and sentenced to extremely harsh punishments, in some cases the death penalty. While in other Soviet republics (Estonia, Lithuania, Georgia, Armenia) clandestine light-industry manufacturing blossomed and its products were available on the black market and even in state-owned stores, in Soviet Ukraine and the Russian Federation such economic initiative was severely penalized. For example, in the early 1960s, the number of Jews sentenced to the death penalty for so-called economic crimes grew fivefold (from 35 to 145), representing 90 percent of all those sentenced to death for economic crimes in Soviet Ukraine.

Only with the ascent to leadership of Mikhail Gorbachev in 1985 and, in particular, the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, did a new generation of business entrepreneurs of Jewish background emerge on Ukraine's economic scene. Among the leading figures are Efim Zvegilsky (mining industry), Ihor Kolomoisky (ferroalloys and banking), Vadym Rabinovych (imported furniture, oil, and the media), Viktor Pinchuk (oil and the metallurgical business), and Mykhailo Brodsky (light industry and hard-currency exchange). Although most Ukrainian oligarchs of Jewish descent support Ukraine's closer integration with Europe, some depend on previous economic ties and, therefore, acknowledge the importance of maintaining strong economic links with the Russian Federation and other former Soviet republics.

Those enterpreneurs who since Ukraine's independence continued economic relations with the post-Soviet east have most recently been forced to reassess their situation. In the wake of the events on Kyiv's Maidan that brought about Ukraine's 2014 Revolution of Dignity, and in response to Russia's aggression and territorial designs on eastern and southern Ukraine, several business oligarchs, whether of Jewish or non-Jewish background, have had to forego potential financial benefits from the east and accommodate themselves to the decidedly pro-European orientation of post-Maidan Ukraine.

Click here for a pdf of the entire book.