Chapter 4.1: "Jews and Ukrainians: A Millennium of Co-Existence"

Jews and Ukrainians: A Millennium of Co-Existence is an award-winning book that explores the relationship between two of Ukraine’s most historically significant peoples over the centuries.

In its second edition, the book tells the story of Ukrainians and Jews in twelve thematic chapters. Among the themes discussed are geography, history, economic life, traditional culture, religion, language and publications, literature and theater, architecture and art, music, the diaspora, and contemporary Ukraine before Russia’s criminal invasion of the country in 2022.

The book addresses many of the distorted stereotypes, misperceptions, and biases that Ukrainians and Jews have had of each other and sheds new light on highly controversial moments of Ukrainian-Jewish relations. It argues that the historical experience in Ukraine not only divided ethnic Ukrainians and Jews but also brought them together.

The narrative is enhanced by 335 full-color illustrations, 29 maps, and several text inserts that explain specific phenomena or address controversial issues.

The volume is co-authored by Paul Robert Magocsi, Chair of Ukrainian Studies at the University of Toronto, and Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern, Crown Family Professor of Jewish Studies and Professor of History at Northwestern University. The Ukrainian Jewish Encounter sponsored the publication with the support of the Government of Canada.

In keeping with a long literary tradition, UJE will serialize Jews and Ukrainians: A Millennium of Co-Existence over the next several months. Each week, we will present a segment from the book, hoping that readers will learn more about the fascinating land of Ukraine and how ethnic Ukrainians co-existed with their Jewish neighbors. We believe this knowledge will help counter false narratives about Ukraine, fueled by Russian propaganda, that are still too prevalent globally today.

Chapter 4.1

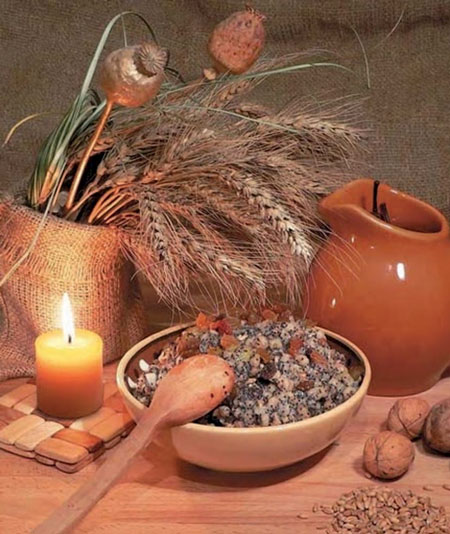

Traditional Culture

Traditional culture refers to the mode of life of a given people as determined by their occupations and economic livelihood. That mode of life may be looked at from two perspectives: material culture (work, cuisine, dwellings, clothing); and spiritual culture (folk customs, religious beliefs, rites, and celebrations). Considering the vast extent of Ukrainian territory, it is not surprising that, while the material and spiritual culture of ethnic Ukrainians may have many common features, there are also regional differences. These are especially noticeable in the geographically less accessible "wooded" areas in the northwest of the country (Polissia and parts of Volhynia) and in the Carpathian far west (Bukovina, southern Galicia, and Transcarpathia).

The following descriptions are for the most part based on the largest territorial portion of Ukraine and reflect the mode of life before the onset of widespread industrialization and urbanization in the twentieth century. Whereas many aspects of the traditional mode of life have disappeared, some are still remembered in modern-day Ukraine and practiced by patriotic intellectuals and other city folk in a kind of ritualistic fashion (especially during holidays and other family and public celebratory events).

Material culture

Dwellings

The predominant type of dwelling among ethnic Ukrainians was the khata, or cottage, found not only in villages but also in towns and even the outskirts of cities. The basic form of the khata, intended for one family, was quite uniform throughout Ukraine. It continues to be widespread, most especially in villages and some small towns, even if the interiors have been modernized with the addition of running water, indoor toilets, electricity, and cooking and heating appliances operated by external sources, usually natural gas.

The typical khata was a three-room structure built out of clay bricks or, in forested areas, out of wooden horizontal logs which might be covered externally with plaster. The structure was generally covered by a hip roof with sloping edges and sides that extended slightly beyond the walls. The three-room interior followed a basic ground-plan: an entrance hallway in the middle; on the left side the living quarters ("kitchen" and sleeping quarters together); and on the right side a storeroom/komora, which might be converted into a second room. In the living-quarters room, the main elements were a large stove and chimney, plank beds along the wall, and one corner reserved for devotional icons. Outside were farm buildings (grain store-houses, barns for threshing, stables, and henhouses), which with the khata comprised the entire homestead surrounded by wattled fences.

The traditional Jewish dwelling in Ukraine looked different both from the surrounding peasant houses on the outskirts of the town and from town dwellings inhabited mostly by Poles. Jewish dwellings were, like those of their ethnic Ukrainian neighbors, built on a stone foundation with walls made of wood, coated with plaster or clay, and then painted. The roof most often was covered by wooden shingles with an internal plastered ceiling and wood floor.

The traditional Jewish dwelling in Ukraine looked different both from the surrounding peasant houses on the outskirts of the town and from town dwellings inhabited mostly by Poles. Jewish dwellings were, like those of their ethnic Ukrainian neighbors, built on a stone foundation with walls made of wood, coated with plaster or clay, and then painted. The roof most often was covered by wooden shingles with an internal plastered ceiling and wood floor.

Very often Jews, like Ukrainians, had carved wooden ornaments around the windows and porch. Yet, unlike the Ukrainian hut which was built for habitation, the Jewish house served a dual function as residence and business, whether in the form of a grocery store, storage for haberdashery and agricultural goods, a tavern, or billiard hall. The residents included the house's owners or leaseholders and their assistants, and sometimes it may even have included a small prayer house. The houses of artisans had their shops and stores facing the street, while the living quarters were hidden in the back. Poor Jews lived in houses identical to those of ethnic Ukrainian peasants with one or two connected rooms and unpaved floors.

The houses of Jewish merchants were large with as many as seven to ten rooms of different sizes. The rooms might be used to accommodate families of relatives involved in the wine-brewing, grain-trade, or tavern-keeping businesses. Merchant houses had all sorts of addenda and dens built along the sides, an external gallery lining the second floor, several stone basements, and a stable for animals in the back.

Since there were no restrictions against residing in the market towns of Ukraine, Jewish merchants preferred to build their houses, which also functioned as stores, along roads that led to and around the marketplace. Each house had a massive windowsill which served as a sales counter. Huge gates opened directly into the building, and through them a wagon could be driven inside and goods unpacked without damage from rain or snow. Very often urban Jews also kept cows, goats, hens, and geese, all of which contributed to the semi-rural character of most Ukrainian towns. Therefore, Tevye the milkman, so well known from the Hollywood film Fiddler on the Roof, was hardly unique. There were hundreds of Tevyes in Ukraine's Jewish shtetls.

Clothing and handicrafts

As in many parts of Europe, clothing styles among ethnic Ukrainians were determined by the social estate to which the wearer belonged: the nobility, townspeople, or peasants. In Ukraine, yet one other social stratum with distinct dress was added to this mix: the Cossacks. By the seventeenth century, the Cossacks had developed a special style of dress: the upper-level military officers and government administrators copied the nobility and wore a caftan (zhupan), although because of military requirements it was shorter and held in with a long silken belt. The rank-and-file Cossack soldiers, otherwise more modestly dressed, were particularly characterized by wide trousers (sharovary), which were later adopted and worn until the nineteenth century by peasants.

Head coverings were an especially important feature of female dress because this element determined an individual's status. Married women (symbolically beginning with a specific act during the marriage ceremony) would, upon rising from sleep, cover their heads and remain so both indoors and outdoors. The most common headdress took the form of a kerchief tied under the neck. The kerchief itself would be decorated with various floral elements through which its wearer was consciously or unconsciously making a statement about her aesthetic values.

Ethnic and Ukrainian and Jewish girls and unmarried women did not cover their heads and could therefore show off their beauty through their hair — the longer, it was presumed, the more attractive. The coiffure might be enhanced by a headband (opaska) around the forehead tied at the back of the head, by braids, or by a garland of flowers. This kind of fancy headband was a shared cultural element among married Jewish and Ukrainian women. The classic look of a Ukrainian female is to this day presumed by some to be based on traditional models, used most recently as a kind of patriotic political branding in the form of a garlanded golden braid surrounding the visage of Ukraine's former prime 93. minister and presidential contender Yuliya Tymoshenko.

Among the most distinctive elements in the traditional dress of ethnic Ukrainians was the home-spun linen shirt (sorochka) worn by both males and females. As a decorative touch to the hemstitching of her handmade shirt, a woman would add ornamentation in bright colors, which gradually developed into elaborate patterns based on geometric design. The sleeves were partially or fully ornamented, as was the collar and bosom. Gradually, male shirts were also decorated with ornamental embroidery (especially those intended as a gift from one's betrothed), although only at the collar, sleeve ends, and the bosom.

Whereas rural villagers, with the exception of a few isolated regions, no longer wear such decorative dress in their daily lives, the embroidered shirt (vyshyvana sorochka) has become in the twentieth century a visual symbol of Ukrainianness and, as such, is often donned by males and females from all walks of life to express pride in their ancestral culture. This includes, as well, politicians and civic leaders who wish to demonstrate their commitment to ethnic Ukrainian cultural values, in particular language, and to the ongoing defense of Ukraine's status as an independent state.

Embroidery, which has become best known through its appearance in shirts and blouses, is only one of the many handicrafts that developed in Ukraine's rural countryside. Among other widespread products were homemade wood carvings, woven rugs (kylyms), and porcelain and faience in the form of pottery, dishes, and painted tiles often intended as decorative coverings for stoves.

Aside from domestic consumption of such practical items, some enterprising individuals developed cottage industries, the sales of whose products brought in needed supplemental income to peasant farmers. Consequently, wood carvers produced candle holders, iconostases, and other implements for churches; weavers sold their kylyms (rugs) at local markets, as did potters and tilemakers their wares. Other village-based handicraft activity that from the outset was geared to production for sale included carpentry for various tools and household implements, cooperage for barrels, and furriery and tanning for clothing and shoes.

While ordinary Jews, both male and female, dressed more modestly, this did not mean the absence of style or fashion. Women wore long skirts of cotton or satin, long-sleeved blouses of calico or demi-cotton covering the chest and collarbone, and velvet aprons. In winter, they donned a short half-length fur coat (zhupan) just like their ethnic Ukrainian neighbors. According to Judaic tradition, women covered their hair with headbands and often added sophisticated brocaded ornaments. Usually made of semi-precious stones and pearls, the ornaments were a distinct feature of the Jewish female dress code that fascinated western European and Russian travelers. The preferred colors were red and blue. In larger cities like Lviv, local Jewish communal authorities (kahal) often issued laws to prevent Jewish women from displaying their jewelry and finery on the Sabbath and holidays so as to instill communal modesty at least on those days.

Men wore ornamented leather boots, long white stockings, trousers to the knee, a silk or cotton shirt with four tsitsis (Heb.: tsitsit — traditional corner fringes symbolizing the 613 commandments) left hanging out, a dark green or blue brocaded vest, and a velvet yarmulke. Their preferred colors were blue and green. Wealthier Jews often imitated the fashion of Polish landlords and ordered their brocaded garments from the same artisans who served the aristocracy. In winter, male Jews wore long fur coats and fur hats, the latter serving as the ritual Sabbath headgear among the Hasidim. The more pious Hasidim also retained the fashion of a traditional Jewish black-silk Sabbath kaftan, which they wore on a daily basis to emphasize the sanctity, purity, and modesty of everyday life.

Economic livelihood and diet

Of all the branches of economic activity, agriculture was historically the most significant for ethnic Ukrainians. Animal husbandry was an important source of livelihood in the Carpathians (sheep and goats) and until the 1860s in southern Ukraine (cattle), while throughout the country agriculturalists depended on the family cow for milk and derivative dairy products, on oxen for transport, and on both for manure. Cattle and oxen were both highly prized, and as such they became an integral part of many folk customs and rituals: the cattle were believed "to talk" at sacred times, as on Christmas Eve; while oxen were given the honor of drawing hearses at funerals. Another special animal species was the bee — the source of honey for human consumption and wax for church candles. Bee-keeping, widespread in Ukrainian lands since pre-historic times, remains a respected and popular "art" among ethnic Ukrainians to this day, the third president of Ukraine Viktor Yushchenko being among the most well-known active bee-keepers.

The traditional diet among ethnic Ukrainians was based on products grown from the land; consumption of meat was limited, and if so mostly pork and its products. In a land dubbed "the breadbasket" of whichever state controlled Ukraine, it is not surprising that the most staple component of the ethnic Ukrainian diet was bread, most frequently dark rye. The wide range of grains (wheat, rye, barley, buckwheat) and vegetables became the basis for the most widespread dishes: kasha (a gruel made of buckwheat or barley); borshch (soup made from red beets and perhaps meat and/or vegetable additives); holubtsi (cabbage rolls stuffed with buckwheat gruel and ground meat); and varenyky (ravioli-like boiled dough triangles filled with potatoes, cheese, or cabbage).

Ethnic Ukrainian homesteads ideally had orchards, whose fruit trees were a source of great pride and the mark of a successful agricultural family. The various fruits were eaten fresh or preserved for the winter months, and certain ones (plums in particular) were used to distill brandies of generally high alcohol content (50 to 70 percent). Such homemade brandies (samohon/horilka) not only became a staple at meals of a festive and celebratory nature but also were offered as a greeting of hospitality whenever anyone would enter the house. Like many of the traditional dishes, alcohol consumption (today usually in the form of store-bought vodka) remains an important component of present-day life among ethnic Ukrainians.

Daily Jewish cuisine followed the strict and highly sophisticated dietary laws of kashrus (Yiddish for "befitting"), which forbade the mixing of dairy and meat products as well as the consumption of non-Jewish wines and bread, and required that meat and fowl be specially slaughtered and salted so that all the blood is drained. While daily meals were modest, Sabbath was a real feast. For that day (Friday night/Saturday), Jews traditionally baked fresh challah-bread and cooked gefilte fish (stuffed carp or pike), cholent (hot stew with barley and potatoes), kishke (stuffed derma), and tsimes (stewed carrots with honey and cinnamon). Perhaps the best-known dish, used as food and medicine, was chicken soup, known even today as the "Jewish penicillin." Each holiday had its special dishes: for example, a boiled fish head for the New Year, latkes (potato pancakes) for Hanukah, and hamantashen (triangular "ears of Haman") cookies filled with poppy seeds or jam for Purim. The Passover dietary laws were particularly strict, since any leavened bread or products thereof were forbidden for eight days. Jews had to make do with unleavened bread (matzo), indulge in vegetables, eggs, and meat, and warm themselves with vodka made not from grain but from potatoes (peisakhuvka).

Jewish women who worked as bartenders or salespersons often hired ethnic Ukrainian female peasants to help them with cooking. This in large part explains the abundance of Ukrainian dishes in Jewish cuisine and of Yiddish forms of Ukrainian words in Jewish kitchen vocabulary: borscht (Ukr.: borshch), kashe (kasha), ogirkes (ohirky), blintses (mlyntsi), varenikes (varenyky), pireg (pyrih), and rogalekh (rohalyky). Jews call their dinner véchere (in Yiddish) from vecherya (in Ukrainian). In reverse, the Jewish word challah entered Ukrainian to the extent that any white braided bread came to be called khala, even in Soviet times. The very warmth of mother's kitchen is remembered by both Jews and ethnic Ukrainians through the same phrase, "mother's apron," whether in Yiddish (mamen fartek) or in Ukrainian (mamyn fartukh).

Spiritual culture

Folk customs among ethnic Ukrainians

Folk rites and customs among ethnic Ukrainians evolved over several centuries, and during that long process they were influenced by the various peoples (Slavic and non-Slavic) and religious traditions that existed in Ukrainian lands: paganism, ancient Greek and Roman rites, and Christianity. In many ways, the success of the "new" religion, Christianity, depended on its ability to accommodate — or re-interpret — the customs and rites of previous belief systems, in order that they would be tolerated by the church. At times, certain pre-Christian practices were suppressed, such as what priests and elders considered to be the erotic excesses accompanying the summer solstice agricultural festival known as the Rite of Kupalo. More often, however, pagan practices were retained after being transformed, that is, Christianized.

Among the pre-Christian beliefs that were proscribed by the church, but that nonetheless survived among ethnic Ukrainians especially (but not only) in rural areas, are those connected with demonological figures. These include goblins (domovyky) — in the form of a cat, dog, dove, sometimes grass snake — who guard the household, help in work, and bring good luck or, if offended, bad luck. There are also a whole host of more dangerous goblins who inhabit the forests (lisovyky), fields (polovyky), and water bodies (vodianyky). The latter control the water-nymphs (rusalky). Water-nymphs are the "unclean" dead, that is, unbaptized children as well as girls and women who died prematurely and/or violently. They often appear in the form of beautiful girls who entice unsuspecting prey (commonly young males) into the water and drown them. Among other ritualistically unclean dead are persons who died in an unnatural manner and who became vampires (upyri), and witches and sorcerers (vidmy-charivnytsi), who can bring about bad weather and cast evil spells that do harm to humans and their domestic animals. Humans are able to protect themselves, or be alleviated of harm already done to them, by consulting mediators, whether charmers (charivnyky), sorcerers (znakhari), or seers (vorozhbyty). Belief in the power of such mediators is present to this very day among ethnic Ukrainians — both rural and urban — especially among young barren women who seek magical help in an effort to have children.

Belief in demons does not imply that pre-modern rural agriculturalists were helpless before the forces of nature. Ethnic Ukrainian peasant farmers acquired over centuries of practical experience a remarkable knowledge of the stars, the sun, and meteorological phenomena, all of which allowed them to predict weather patterns and adjust their agricultural and animal-husbandry work accordingly. Similar extensive experience with plants resulted in the development of remedies for a variety of ailments, some of which are still used because they have proven to be more effective than solutions proposed by modern medical practices.

Aside from popular — some would say superstitious — ethnic beliefs, Ukrainian society is characterized by a wide range of traditional folk rites and customs. Those associated with the family are connected with the three basic phases of the life cycle: birth, marriage, and death. Of the three, marriage customs are perhaps the most elaborate; certain aspects of the traditional three- to four-day, even week-long, wedding celebration are still practiced today, although in a much-abbreviated form.

The other kind of folk rites and customs are those that are celebrated in the public as well as private sphere, often as holidays that are officially recognized by the state as a day (or days) of rest. While these rites were originally connected with the four seasons — winter, spring, summer, autumn — and with the agricultural activity that went with each of them, in many cases they have been Christianized and made an integral part of the church calendar.

The most elaborate of these are within the winter cycle and are specifically connected with Christmas. The Christmas season begins with a feast day that nicely encapsulates pre-Christian and Christian belief systems. Celebrated on 21 November/4 December, it formally closes the autumn season of agricultural work, after which it is not proper for the next nine weeks to till the earth or to disturb it in any way. The tradition of stopping outdoor work was transformed by the church into the beginning, or advent, of the Christmas season marked by the Feast of the Presentation of the Mother of God (Vvedennya), who was chosen to give birth to the Messiah four weeks later.

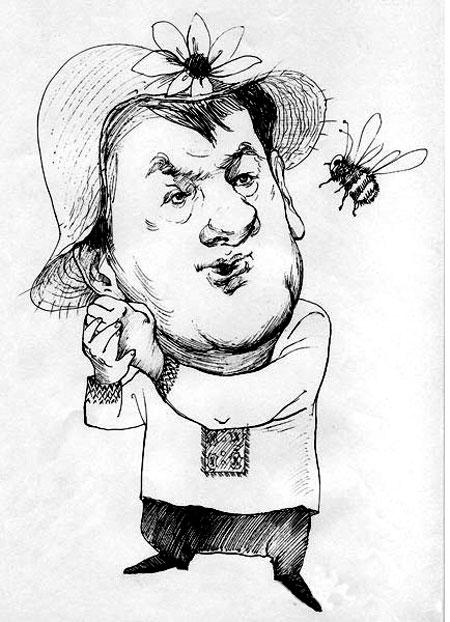

The focal point of the winter cycle is Christmas itself, beginning on Christmas Eve (Svyat-Vechir), 6 January, and ending on Epiphany (Vodokhryshchi or Yordan), 19 January. Christmas Eve begins with an elaborate meal (usually twelve dishes) with members of the immediate family, a custom that combines respect for the earth's agricultural bounty and commemoration of ancestors. The homestead's animals are accorded particular respect (they are given food from the table and sometimes are fed first), while sheaves of grain are placed on the table and hay and straw strewn underneath. Such symbolic acts accord respect to the sources of sustenance for humans and animals, as well as recalling the biblical story of the Christ child having been born in a stable among the animals, specifically in a manger (a feeding trough for livestock) filled with straw. The family meal is followed by going to church at compline, the last liturgical prayer of the day, said after nightfall or before retiring. The following Christmas Day, 7 January, is one of visitation by members of the extended family, friends, and neighbors from household to household. Among the visitors may be carollers who are hosted with food and drink in gratitude for the Christmas ritual songs (kolyadky) they sing or the Christmas-story skits (vifleyimtsi: Bethlehem plays) they perform.

Of all the traditional rites and customs handed down from the past, those connected with Christmas Eve and Christmas Day are still preserved by many ethnic Ukrainians whether they are faithful or only nominal Christians. Diaspora communities, in particular, are committed to observing Christmas ceremonial rites and customs as an expression of their Ukrainianness. The larger societies in which Ukrainians live sometimes reinforce the ethnic-identity aspect of the Christmas holiday. Since Ukrainian churches of the Eastern rite follow the old, or Julian, calendar (two weeks later than the Gregorian, or Western "norm"), Christmas falls on 6–7 January, not 24–25 December. In countries like Canada, the mainline media often speak of the 6–7 January holiday as "Ukrainian" Christmas, even though technically it is the holiday of Eastern-rite Christians of other ethnic backgrounds as well.

The other major holiday among ethnic Ukrainians, Easter, comes during the spring cycle. It, too, combines ancient rites related to the rebirth of nature and plant life with the ultimate Christian message — the death by crucifixion of the Messiah and presumed son of God, Jesus Christ, on Good or Passion Friday (Velyka/Strasna pyatnytsya) and his resurrection from the dead three days later on the early morn of Easter Sunday (Paska/Velykden — The Great Day).

The spring cycle of customs and rites actually begins on 25 March/7 April, when cattle are first brought outdoors for pasturing. This "coming-out" has become the Christian holiday called Annunciation, the day on which the angel Gabriel announced to Mary, the mother of the Messiah, that she was with child. Other Easter customs that reflect the celebration of the gifts of nature include: (1) rites around the early spring plant whose name is given to the first day of Easter week, known as Flower, or Willow Sunday (Kvitna/Verbna nedilya, and in the West as Palm Sunday), the day Jesus rode triumphantly into Jerusalem; (2) the exchange of elaborately painted eggs (krashanky, pysanky) as a symbol or nature's rebirth coincident with Christ's resurrection; and (3) further celebrations on Easter Monday and Easter Tuesday, which are accompanied by spring songs (vesnyanky) addressed to the birds who have returned and by "water-fights" (sprinkling or even dousing) initiated in turn by males and females in recognition of the life-giving properties of water for plant life and, if blessed by the church, for one's soul.

Despite the pagan and secular origins of many customs and rites, Easter, like Christmas, remains a Christian holiday. Attendance at church, therefore, is considered essential. In ethnic-Ukrainian communities whether in the homeland or in the diaspora, the holy liturgy on Easter, which traditionally begins at midnight, is not only a profound religious experience for believers but also a major public spectacle in which Eastern-Christian Ukrainians, whether or not they are believers, like to take part. It is not uncommon today to see thousands of attendees at the Easter (holy liturgy) packed into a church or, more likely, standing in the streets and squares outside listening on loudspeakers to the religious service and eagerly awaiting the moment when the priest emerges to bless with holy water their baskets filled with homemade foods surrounding the paska (Easter bread) that will be consumed at the festive Easter-day family meal.

Click here for a pdf of the entire book.