Chapter 5.1: "Jews and Ukrainians: A Millennium of Co-Existence"

Jews and Ukrainians: A Millennium of Co-Existence is an award-winning book that explores the relationship between two of Ukraine’s most historically significant peoples over the centuries.

In its second edition, the book tells the story of Ukrainians and Jews in twelve thematic chapters. Among the themes discussed are geography, history, economic life, traditional culture, religion, language and publications, literature and theater, architecture and art, music, the diaspora, and contemporary Ukraine before Russia’s criminal invasion of the country in 2022.

The book addresses many of the distorted stereotypes, misperceptions, and biases that Ukrainians and Jews have had of each other and sheds new light on highly controversial moments of Ukrainian-Jewish relations. It argues that the historical experience in Ukraine not only divided ethnic Ukrainians and Jews but also brought them together.

The narrative is enhanced by 335 full-color illustrations, 29 maps, and several text inserts that explain specific phenomena or address controversial issues.

The volume is co-authored by Paul Robert Magocsi, Chair of Ukrainian Studies at the University of Toronto, and Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern, Crown Family Professor of Jewish Studies and Professor of History at Northwestern University. The Ukrainian Jewish Encounter sponsored the publication with the support of the Government of Canada.

In keeping with a long literary tradition, UJE will serialize Jews and Ukrainians: A Millennium of Co-Existence over the next several months. Each week, we will present a segment from the book, hoping that readers will learn more about the fascinating land of Ukraine and how ethnic Ukrainians co-existed with their Jewish neighbors. We believe this knowledge will help counter false narratives about Ukraine, fueled by Russian propaganda, that are still too prevalent globally today.

Chapter 5.1

Religion

Ethnic Ukrainians, like most peoples in Europe, were originally pagans. Their early belief system was similar to that of other Slavs and reflected the concerns of people who depended on agricultural crops and domestic livestock (especially cattle) for their survival. In response to their fear before the mysteries of nature, Slavs believed in divinities found in the clouds and on earth, whether in forests and rivers or closer to home in their own fields and stables. Among the major gods were those, it was believed, who represented and controlled the forces of nature, in particular storms and thunder (Perun), the sun (Dazhboh), fire (Svarih), and cattle (Veles). There were, as well, minor gods or demonological figures, believed to guard the household and inhabit forests, fields, or bodies of water and whose potential anger needed to be assuaged.

Although a few statues and sacrificial sites to the major pagan gods were erected (especially in Kyiv), for the most part the early Slavic religion was of a more personal nature. This allowed the individual to have what was believed to be direct communication with the sacred deities and not have to depend on diviners, priest-like figures, or any other intercessors.

Christianity

All this began to change in the late tenth century, when the ruler of Kievan Rus', Grand Prince Volodymyr/Vladimir ("the Great," r. 980–1015), decided to adopt for his realm a more advanced religion. As later medieval chronicles report, Volodymyr allegedly researched the religions which were dominant at the time in neighboring states: Islam, Judaism, and Christianity according to both its Western (Roman Catholic) and Eastern (Orthodox) variants. As legend has it, Orthodox Eastern-rite Christianity, as practiced in the Byzantine Empire, won the day. Actually, Christianity had reached Ukrainian lands even earlier, with adherents and churches in Crimea dating from the sixth century and in far western Transcarpathia and Galicia from the ninth and early tenth centuries. Volodymyr's conversion, however, is the act that has been hailed ever since as the definitive Christianization of Rus', even though it took several more centuries before that religion took firm root among all the inhabitants of Kievan Rus'.

Given that Christianity was imposed from above by the secular ruling authorities, the ancestors of modern-day ethnic Ukrainians and other East Slavs were expected to forget their multifarious pagan gods and adopt the idea of one omnipotent God who created the earth and everything upon it. Christianity derived from the monotheistic world of Judaism, with its belief in one God and the expectation of a Messiah whom God would send to save humankind from its sins. Christians not only revered the Jewish prophets, who predicted the coming of the Messiah, they believed that the Messiah had actually come in the person of Jesus Christ, a Jewish prophet from Palestine born sometime around the year one of the Common Era (ca. 3758–60 according to the Jewish calendar).

Christians parted company with the Jews. Or, put another way, some Jews who believed that Jesus was the Messiah became followers of Christ (Christians) after his death by crucifixion about 30 CE. These early Judeo-Christians, who initially retained their Jewish identity and maintained Judaic rituals, formulated the basic precepts of Christian belief: that Christ was raised from the dead and that he resides for eternity with God in heaven until the Day of Judgment, when he will return to resurrect from the dead all those who truly believed in Him during their earthly lives. While pagan gods might protect a person from the dangers of daily existence on earth, the Christian message promised salvation and everlasting life after one's death. By the fifth century, the established Christian church forbade its adherents from following Judaic rites such as circumcision and observance of the Sabbath (moving the holy day to Sunday), and it proclaimed that only a belief in Jesus as the Christ (Savior) secured one's final salvation.

Volodymyr's act of personal conversion and proclamation of Eastern Christianity as the official religion of his realm sometime around 988 has been celebrated in subsequent centuries by all peoples who claim cultural descent from Kievan Rus', namely, modern-day Russians and Belarusans as well as Ukrainians. Already during medieval Kievan Rus', there developed a gradual fusion of identities, whereby an inhabitant of the Rus' land and Orthodox Christianity came to mean the same thing. In more modern times, a popular assumption arose that one could not be of Ukrainian, or Belarusan, or Russian nationality unless one were an Eastern-rite Christian. Because of his seminal role in bringing Christianity to the East Slavs and initiating the merger of religious and national identities, Kiev's late tenth-century grand prince was canonized (raised tenth to sainthood) by the Orthodox Church and is venerated to this day by Ukrainians, Belarusans, and Russians as "their own" St Volodymyr/Vladimir.

Judaism

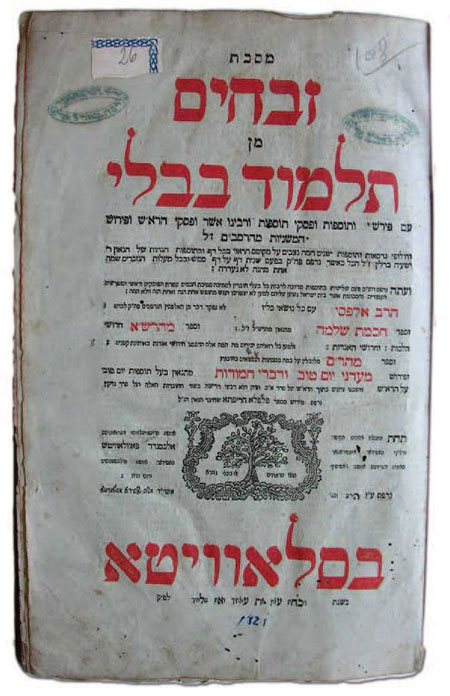

The Jews emerged as a monotheistic people whose religion, Judaism, was based on the belief in a one, absolutely sovereign God — an invisible and incorporeal divine being that created the world, revealed Himself through Abraham to the Jews, redeemed them from Egyptian bondage, and singled them out among other nations as His chosen people. The mutual agreement and dependence of the Jews on their God was reflected in the first five books (Pentateuch) of the Bible, known as the Torah. These, together with two other books, the Prophets (Neviim) and Writings (Ktuvim), formed the Hebrew Bible. The Torah lies at the center of the Jewish tradition, a complex system of prescribed beliefs and established practices derived as much from texts (the "written" Torah) as from customs and rites (the "oral" Torah). In a word, the "oral" Torah can be seen as an extended commentary on the written Torah, in which the commentator is either an individual Jew or a Jewish community whose way of life is itself a form of a commentary. Subsequently, the "oral" Torah, that is, the ways of doing things in a Jewish manner, was also written down. It took the form of the Mishnah (2nd –3rd century CE) and a commentary on it known as the Gemarah (3rd–7th century CE). The Mishnah and Gemarah together form the Talmud, which by the eighth century CE became a canonical (sealed and classical) book.

Rooted in Abrahamic rituals and beliefs, the Oral Torah has changed with the evolution of the Jewish people, manifesting itself in rabbinic writings, commentaries on the sacred texts, Midrash liturgical compositions (rabbinic narratives or tales), legal sources, rabbinic responsa, and many other written forms. While the written Torah is a reflection of only one part of the vast Oral Torah tradition, the latter is a way of life and thinking for which the written Torah serves a blueprint. Jews can be seen as the People of the Book in the sense that they view and interpret their holy writ through the prism of customs and beliefs of the Oral Torah, a fluid and heterogeneous commentary on the key written text of the Judaic tradition.

Jewish beliefs may have been drawn from various heterogeneous customs, but they had one aspect in common: the conviction that redemption could be achieved communally if the Jews follow the 613 divine commandments of the Oral Torah. In other words, redemption is achieved through practice, through what the Jews do. Belief, therefore, is rather secondary. Since the commandments protected everyday Jewish life, the entire spectrum of Jewish beliefs focused primarily on this world, not on the afterlife. While Jews did make references to the world to come, to utopian messianic times, and to the sufferings of sinners and joyous life of the righteous in the other world, these beliefs were neither canonized nor obligatory.

The Talmud invoked a famous verse from the Psalms, "the dead ones will not praise You," in order to underscore that it was up to the living to perform acts of loving kindness and elevate the glory of the Divine Name. Thus, Jews had no elaborate vision of the afterlife, no sophisticated tripartite conceptualization of paradise, purgatory, and hell like the Catholics, and no dual netherworld of paradise and hell like the Eastern Orthodox. The Jews knew that gehinnom (a place where the wicked are punished after death) existed, and some also believed that they had to wait about twenty years to get there after they died, but what it was and how rewards and punishments were distributed remained unclear. For centuries, rabbinic scholars reiterated the view that knowledge of what happened in gehinnom was unnecessary. In short, Jews should be concerned about what they did in this life. The rest was commentary.

The European version of traditional Judaism, called Ashkenazic Judaism, reflected the above principles based on practice rather than on an all-encompassing theological system. The beliefs of eastern and central European Jews were rooted in everyday life, with religious practices stemming from the 613 commandments of the Oral Torah tradition. Some of these commandments became obsolete following the destruction of the Jerusalem Temple in 70 CE, while others made sense only in the land of Israel or during the messianic era. As for the rest, about two hundred, they remained a requirement for every Jew.

These obligatory two hundred or so commandments regulate the theological relationship of the individual with God, as well as the social relations between humans. They include the Decalogue (Ten Commandments); the laws of the Sabbath and festivals; ritual observance and worship at home and in the synagogue; family law (including regulations of marriage and divorce); the dietary regulations concerning the preparation and consumption of food (including the requirement to use only ritually slaughtered kosher animals); ritual purity in sexual relations (including a prohibition against intimacy during a female's menstruation); civil law (property and transactions, including Jewish-Christian relations in business and the responsibility of a keeper of someone else's property); criminal law; and the general requirement not only to live according to the laws of Judaism but also to study them to prepare oneself for the coming of the Messiah (who, for Jews, has not yet come).

Organizational structures

Following the Byzantine model, the Orthodox Church was closely associated with, and in many ways subordinate to, the state. Hence, Volodymyr/ Vladimir and his successors, especially Grand Prince Yaroslav ("the Wise," r. 1036–54), took the lead in creating a highly structured church organization. Eventually, all of Kievan Rus' was divided into eparchies (the Eastern equivalent of dioceses), administrative units each headed by a bishop.

The entire eparchial structure was headed by a metropolitan (the Eastern equivalent of archbishop), who was considered the highest religious authority in Kievan Rus'. The seat of the metropolitan carried great symbolic value, which initially was the city of Kyiv, the political, economic, and cultural center of Kievan Rus'. Within each eparchy, religious communities (parishes) were served by priests (males only), who were responsible to the bishop of the eparchy in which the community was located. The Eastern Church also developed religious communities comprised of either males (monks) or females (nuns), who resided in monasteries or convents. In contrast to priests who served individual communities, members of monastic orders lived in closed communities whose main goal was a life of prayer (contemplation) and service on behalf of the church (production of church garments and other ritual items, copying and later printing religious texts, etc.).

Priests as spiritual and civic figures

The clergy, whether priests, monks, or nuns, were generally held in high esteem by both believing and nominal Eastern Christians. The reason for this was twofold: not only were they doing "God's work," they were the only instrument through which an individual could commune with God through His Son and humankind's savior, Jesus Christ. Access to that divine world was through a religious rite known as the holy liturgy, whose supreme moment was communion — the partaking of bread and wine which not only symbolized but that was believed to be miraculously transformed into the body and blood of the crucified savior. Only a sanctified Orthodox Eastern-rite clergyman had the authority to grant a believer communion during the holy liturgy, as well as to conduct other sacred rituals connected with the human life cycle: baptism after the birth of a child; marriage; and the last rites at a funeral after death. Aside from their monopoly in sacred matters, Ukraine's Eastern Christian clergy often influenced their flock's relationship to the secular world in which they lived. At times that influence had negative repercussions, especially with regard to non-Christian neighbors such as Jews. For example, the widespread view throughout Christian Europe that Jews were responsible for the murder of Christ was a message that often entered the homilies and sermons of Ukraine's clergy. Such allusions may have encouraged spontaneous acts of violence against Jews, especially during the Easter season.

Somewhat more positive was the Eastern Christian clergy's position regarding the national language and identity of their flock. Here, however, the role of the Church was mixed, even contradictory. Some clergy, especially among the Orthodox in the Russian Empire, were very prominent in promoting the idea that Ukrainians (in their terminology "Little Russians") were part of the Russian nationality and should be educated in the Russian language. In fact, some of the leading proponents of the view that a Ukrainian language and nationality did not even exist came from the ranks of the Orthodox clergy, in particular several bishops who, while natives of Ukraine, were among the Russian Empire's leading Ukrainophobes.

On the other hand, in Habsburg-ruled Austria-Hungary, the Greek Catholic clergy in Galicia and to a lesser degree in Transcarpathia were known for their work in defense of a Ruthenian/Ukrainian identity. Some priests were among the group's leading national poets, writers, and scholars, while at the grass-roots level village priests and their wives often functioned as elementary school teachers who imbued in their students at an early age a lasting sense of Ukrainian patriotism. Perhaps the ultimate symbol of the intimate relationship between nationality and religion was Metropolitan Andrei Sheptytskyi, who, as head of the Greek Catholic Church in Galicia during virtually the entire first half of the twentieth century, came to be considered a Moses-like patriarch of his Ukrainian flock. The dichotomy between pro-Ukrainian Greek Catholic and pro-Russian Orthodox (especially under the Moscow Patriarchate) clergy has continued at least until the first decade of the twenty-first century.

Rabbis as spiritual and social figures

Jewish tradition manifested itself in and was impossible beyond the Jewish community. That community took various forms depending on time, place, and other factors (economic, political, and demographic). From the fourteenth to early twentieth centuries in Ukrainian lands as well as throughout central and eastern Europe, the standard Jewish community called itself the kehillah kedoshah, or holy community.

Rabbis were among the most important communal figures. They acted as legal (halakhic) authorities, helping Jews decide everyday issues related to rites and rituals. Twice a year, on the eve of Passover and before the Day of Atonement (Yom Kippur), the rabbi in a traditional pre-modern community gave a long sermon in the synagogue. The rabbi also officiated at wedding and funeral ceremonies, issued divorce documents, and acted as the local judge, who together with two assistants for civil and criminal law formed the rabbinic court (Heb.: bet din; Yid.: bezdn). In many cases, the rabbi also acted as a teaching authority for several students in his ye-shivah, or Talmudic academy. Many famous rabbis studied in Ukraine's small Talmudic academies — before the 1800s with at most a half-dozen students each — in Ostroh, Brody, and Volodymyr-Volynskyi, among other places.

The rabbi was usually surrounded by other Jews, well educated but lacking rabbinic ordination, who belonged to the so-called secondary intelligentsia. While a community could function without a rabbi, it could not do so without this group of people. Within this group were: the shoykhet (butcher, responsible for the ritual slaughter of fowl and cattle); the mohel (in charge of circumcision); the maggid (preacher who gave weekly sermons in a synagogue); the mokhiakh (the so-called rebuker, a type of a preacher especially popular in eastern Europe, who chastised the community about its transgressions); the soyfer (scribe, responsible for the Torah and other sacred texts, and also for marriage [ketubah] and divorce [get] documents); and, finally, the least educated among them, the melamed (elementary school teacher). Because of their ongoing daily interaction with ordinary Jews, these representatives of the communal infrastructure had a much greater impact on the hearts and minds of the local Jews than did the rabbi.

Although the rabbi was an authority in Judaic law, he was not the head of the community. That role was played by the kahal, an umbrella organization comprised of the local mercantile elite comparable to a modern board of synagogue trustees, which hired a rabbi either for a certain term or permanently. The rabbi served on the board of the kahal and approved its decisions. Because the kahal was a secular institution modeled along the lines of a town council, the authoritative signature of a rabbi on a kahal document made it a binding communal regulation. Local kahals reported to the Council of Four Lands, the central organ of Jewish communal autonomy in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. Many rabbis served as members, and because of their presence the Council attained the right to issue regulations that were binding for eastern European Jews at large. The abolition of the Council of Four Lands in 1764 created a power vacuum in Jewish life, which in Ukraine came to be filled by the religious revival movement — Hasidism.

The organizational structure of the Jewish community was permeated by the communal understanding of Judaic law. In their everyday behavior, Jews were not governed directly by the Torah or the Talmud. Rather, the laws in those texts were interpreted, explained, canonized, and brought together in the halakhic codices (from the word halakhah — "walking" according to the precepts of the law) by rabbinic scholars, who made them known to the community through sermons, communal practices, and published codices. Among the best-known of the halakhic codices, which first appeared under the influence of Muslim rationalism among Sephardic Jews, are the Mishne Torah authored by Maimonedes (Rabbi Moshe ben Maimon, or the Rambam) and the sixteenth-century Shulkhan Arukh (A Set Table) compiled by Yosef Karo.

Interpreting the law and adapting it to specific cases was the rabbi's task. For example, what should a village tavern-keeper do to attend to his customers, when on the Sabbath he and his family were not allowed to work according to the precepts of Judaism? What were Jews to do when living in villages where there was no ritual bath? What should be done to a transgressor whose immoral behavior jeopardized the reputation of the entire Jewish community? Could a married Jewess (agunah), whose husband had gone to a distant marketplace and disappeared, remarry?

Rabbis in Ukraine treated these and other questions in the so-called responsa literature, or SHU" T (acronym of the Hebrew: sheelot u-teshuvot, questions and answers). Responding to questions from individuals and entire communities, the rabbis sent back answers that people would consider as binding as the laws of the Torah. Among rabbis who came to enjoy renown and influence both during and after their service to Jewish communities in Ukraine were Joel Syrkes of Medzhybizh (Mezhbizh), Yehezkel Landau of Yampol, and Josef Shaul Natanson of Lviv. Jewish communities also had multiple havurot, grass-roots volunteer institutions responsible for the communal performance and reinforcement of certain commandments. The wealthiest and most influential among them was the Burial Society (Hevrah kadishah), responsible not only for proper burial according to Judaic ritual but also for the establishment of other voluntary societies in the community. Many societies, such as that of the Lutsk Tailors (Hevrat hayatim), brought together representatives of a certain professional group, who would then care for their own needy, supervise a balanced distribution of commissions, and oust unwelcome competitors. In addition to professional societies, there were also philanthropic ones concerned with specific needs (Bread for Travelers, Dowries for Poor Girls, and Clothes for the Needy), economic development (Free Loan Society), education (Mishnah and Talmud Study Society), or liturgical functions (Psalms Readers). There were also groups of Jews who helped other communal organizations function properly: for example, book restorers (Tikun sfarim) and coffin-carriers (Nosei ha-mitah). Each society had its own statutes and a record book (pinkas) containing the proceedings minutes of the organization, the names of members, and other details. The pinkas was not only an important record of the internal structure of the society; its very existence as a book was believed to have a protective magic power.

Click here for a pdf of the entire book.