Chapter 5.2: "Jews and Ukrainians: A Millennium of Co-Existence"

Jews and Ukrainians: A Millennium of Co-Existence is an award-winning book that explores the relationship between two of Ukraine’s most historically significant peoples over the centuries.

In its second edition, the book tells the story of Ukrainians and Jews in twelve thematic chapters. Among the themes discussed are geography, history, economic life, traditional culture, religion, language and publications, literature and theater, architecture and art, music, the diaspora, and contemporary Ukraine before Russia’s criminal invasion of the country in 2022.

The book addresses many of the distorted stereotypes, misperceptions, and biases that Ukrainians and Jews have had of each other and sheds new light on highly controversial moments of Ukrainian-Jewish relations. It argues that the historical experience in Ukraine not only divided ethnic Ukrainians and Jews but also brought them together.

The narrative is enhanced by 335 full-color illustrations, 29 maps, and several text inserts that explain specific phenomena or address controversial issues.

The volume is co-authored by Paul Robert Magocsi, Chair of Ukrainian Studies at the University of Toronto, and Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern, Crown Family Professor of Jewish Studies and Professor of History at Northwestern University. The Ukrainian Jewish Encounter sponsored the publication with the support of the Government of Canada.

In keeping with a long literary tradition, UJE will serialize Jews and Ukrainians: A Millennium of Co-Existence over the next several months. Each week, we will present a segment from the book, hoping that readers will learn more about the fascinating land of Ukraine and how ethnic Ukrainians co-existed with their Jewish neighbors. We believe this knowledge will help counter false narratives about Ukraine, fueled by Russian propaganda, that are still too prevalent globally today.

Chapter 5.2

Religious diversity among Ukrainians

As in other parts of Europe, the evolution of Christianity in Ukraine was characterized by internal dissension, which led to the formation of several different strains of belief, jurisdictional authority, and church bodies that often were antagonistically opposed to one another. Initially, there was one Christian Church that followed different rites and that had different supreme hierarchs: the Latin-language Roman-rite Catholic Church based in Rome under the pope; and the Greek-language Byzantine-rite Orthodox Church based in Constantinople under the ecumenical patriarch. Beginning in 1054 and culminating at the outset of the thirteenth century, these two branches of one Christian Church split into the Western Roman Catholic Church and the Eastern Orthodox Church. Ukrainian lands were — and remained within — the sphere of the Byzantine-rite Eastern Orthodox Church.

Orthodox and Uniate/Greek Catholics

When, in the second half of the sixteenth century, Ukrainian lands were part of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth — an officially Roman Catholic state — active consideration was given to uniting the two major components of the Christian world. As it turned out, a church union encompassing the entire Orthodox and Catholic worlds was not achieved. Instead, only some Orthodox accepted the idea of union and, after 1596, became part of what was called the Uniate Church. Uniates did not consider themselves converts to Roman Catholicism. Rather, they thought they had returned from schism to the fold of the one universal Catholic Church in which they were allowed to maintain the basic beliefs and rituals they had as Orthodox: a liturgy that used Church Slavonic (instead of Latin as among Roman-rite Catholics); the possibility of married men being ordained as priests; maintenance of the "old" Julian calendar (in which certain fixed feasts like Christmas were celebrated two weeks later than the new Western Gregorian standard); and several points of dogma and ritual that differed from the Roman-rite. In effect, Uniates were no different from the Orthodox except for one important point. The Uniates, like Roman Catholics, recognized the pope in Rome as head of the Church, while the Orthodox continued to recognize the ecumenical patriarch of Constantinople as the head of their church, albeit a symbolic one.

The split between Uniates and Orthodox among ethnic Ukrainian Christians remains in place to this day both in the homeland and in the diaspora. The Uniates, who date from the late sixteenth century, were subsequently renamed Greek Catholics (1774), then in the twentieth century Ukrainian Greek Catholics, or simply Ukrainian Catholics. Meanwhile, the Ukrainian Orthodox have experienced an even more complicated evolution. Unlike in the Roman Catholic Church, with its universalist jurisdiction regardless of the ethnic and national (state) composition of its adherents, the Orthodox world adopted the practice of forming national churches. Hence, there evolved jurisdictionally distinct bodies, such as the Russian Orthodox Church, the Serbian Orthodox Church, the Greek Orthodox Church, and so on. Having one's own jurisdictionally independent (or autocephalous) Orthodox Church and ruling hierarch (patriarch or metropolitan) became a goal that, if achieved, was a source of pride for any new nation-state.

As part of the expansion of the Tsardom of Muscovy and Russian Empire into Ukrainian lands, the local Orthodox Church in Ukraine was forced after 1686 to switch its jurisdiction from the ecumenical patriarchate in Constantinople to the patriarch of the Russian Orthodox Church in Moscow. Later, in the early twentieth century, when Ukrainians strove to create an independent state, some Orthodox adherents wanted their own church jurisdiction. The result was the creation in 1920 of a Ukrainian Autocephalous Orthodox Church.

The autocephalous movement for a jurisdictionally distinct Orthodox church in Ukraine was suppressed by the Soviet regime; however, on the eve of Ukraine's independence in 1991, the movement was revived. The Ukrainian Autocephalous Orthodox Church was legally reconstituted, and before long yet another body came into being: the Ukrainian Orthodox Church — Kyiv Patriarchate. Hence, today there are three Orthodox jurisdictions in Ukraine, each of which is trying to gain adherents at the expense of the others: the Ukrainian Orthodox Church — Moscow Patriarchate; the Ukrainian Orthodox Church — Kyiv Patriarchate; and the Ukrainian Autocephalous Orthodox Church. Each has its own full-fledged hierarchical structure headed by either a patriarch or metropolitan archbishop. The attitude of these various church jurisdictions toward the Ukrainian nationality and toward the national orientation of the state differs. The Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church has maintained its tradition of emphasizing the use of the Ukrainian language and association with patriotic events and figures from the past. Among the Orthodox, the Autocephalous Church adopts a similar position, as does to a certain degree the Kyiv Patriarchate. Each of these three churches sees itself as a patriotic alternative to the Ukrainian Orthodox Church within the jurisdiction of the Moscow Patriarchate. The latter body since Ukraine's independence in 1991 has adopted a rather mixed attitude. Whereas this church continues to include hierarchs, priests, and lay parishioners who are not sympathetic and in some cases openly opposed to Ukrainian national values (the use of Church Slavonic instead of Ukrainian in church services is symbolic of such attitudes), there are nevertheless clerics and lay adherents who consider their church a distinctly Ukrainian body deserving of greater jurisdictional autonomy (perhaps the status of an exarchate) while remaining in communion with the Moscow Patriarchate.

Protestants and sects

At the outset of the sixteenth century, the same time the Ukrainians of Poland-Lithuania first became divided into Orthodox and Uniates, Christian Europe faced another serious challenge, the breaking away from the Roman Catholic Church of reformers known as Protestants. Initially, Protestantism did not make any serious inroads into Ukrainian-inhabited lands, but in the nineteenth century a small number of ethnic Ukrainians converted to various Baptist and Evangelical churches. Those churches slowly grew in size, although it was not until the end of the twentieth century, following the collapse of the Soviet Union, that the largest number of conversions took place. Today the most numerous Protestant communities in Ukraine are the Baptists and Pentecostals, followed by an increasing number of communities classified as "sects": Seventh-Day Adventists, Jehovah Witnesses, and others.

Whether or not the adherents of the various Christian groups are, or have been, ethnic Ukrainians, the churches themselves have often been in an antagonistic relationship with each other. This applies to both past and present relations between Orthodox and Uniate/Greek Catholics, between the various Orthodox jurisdictions, and on the part of Orthodox and Greek Catholics toward Protestants, most of whom are derisively dismissed as "sects."

Religious diversity among Jews

Jewish communities in Europe traditionally followed various practices while at the same time observing one set of religious values. This changed in the early nineteenth century, when the Reform movement arose and Orthodoxy emerged to check its advance. The Reform and the less radical Conservative movement, both of German origin, made only a limited impact on the Jewish community in Ukrainian lands.

Hasidim and their opponents

A split of a different character, however, did occur within Ukraine's traditional Jewish community. Late in the eighteenth century, the followers of a new movement known as Hasidism, along with their opponents, the Litvaks, came onto the scene. In contrast to central Europe, the basic division among Jews in Ukraine was not between Orthodoxy and Reform, but rather among the Orthodox who follow different forms of traditional Judaism: the Hasidim, and their opponents, the Litvaks (mitnagdim).

Hasidism arose in the second half of the eighteenth century among isolated groups of pious Jews in west-central Ukraine (Podolia and Volhynia). It derived from a branch of Jewish mysticism known as Kabbalah, which in the late seventeenth century had galvanized rabbinic elites and the secondary intelligentsia among Jews in Ukraine. The spread of Kabbalah was in large part a result of the arrival of a small number of Sephardic (formerly Iberian) Jews from the Ottoman Empire, who had come to Ukraine after the Ottomans had captured most of Podolia in the 1670s.

The Kabbalistic ideas and practices brought to Ukraine were based on the following precepts: the immanence of the divine; the hidden spiritual meaning of everything in the world around; the possibility of each human being reaching God through mystical contemplation; and the practice of ascetic piety as a means to change the world (tikkun). The early Kabbalists in Ukraine called themselves hassidim. They practiced regular ritual ablutions; fasted from Sabbath to Sabbath, eating just a morsel of bread with water after sunset; left their homes for voluntary exile; suppressed their physical urges; and engaged in group study of major books of Jewish mysticism, such as the Sefer ha-Zohar (Book of Splendor, ca. 1290).

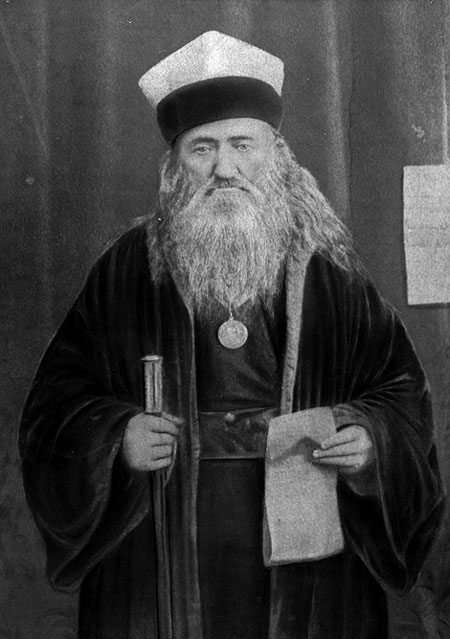

Hasidism as a full-fledged social movement traces its origins to a Kabbalist from the Podolian town of Medzhybizh (Mezhbizh). He was Israel ben Eliezer, better known as the Baal Shem Tov or the Besht, which is the acronym for "Master of the Divine Name". Although he and many of his earlier followers had studied in a Kabbalist kloyz (a kind of elitist club of mystics), they rejected the ascetic form of piety of the previous hassidim. Instead, they practiced enthusiastic religiosity, fusing eastern European piety and new forms of Kabbalah. Calling themselves Hasidim (scholars use a capital letter for them to differentiate them from the ascetically pious hassidim), they organized their own prayer groups, endorsed the study of esoteric sources among ordinary Jews, and published books explaining the secret meaning of the basic Jewish written sources. They also insisted on stricter laws of ritual slaughter and argued that everyone, even the most illiterate Jew, could speak to the Almighty through mystically inspired prayer.

The mitnagdim, those rabbinic scholars and ordinary Jews who were in opposition to Hasidism, rejected what they considered the excessive emotionalism of Hasidic prayer, the replacement by the Hasidim of the Ashkenazic liturgy with Sephardic prayer rites, and the popularization of sublime and elitist Kabbalistic wisdom. The center of the mitnagdim was not in Ukraine but in Lithuania (Vilnius), and this was one of the reasons why the enemies of the Hasidim came to be associated with the Litvaks, or Lithuanian-rite Jews. There were rabbis also in Ukraine who opposed the Hasidim, but they were unable to undermine the enormous popularity of the new movement and its mass appeal. In practice, the relations between the Hasidim and the mitnagdim in the Ukrainian lands of the Russian Empire were not strained. This was in stark contrast to Belarus and Lithuania in the northern part of the Pale of Settlement, where clashes were not uncommon. Therefore, a Jew in Ukraine might use a traditional Ashkenazi prayer-book and avoid the noisy gatherings of the Hasidim, but, urged by his wife, he might still go to a Hasidic master for a blessing or counsel. Although initially the Jewish authorities considered the Hasidim dangerous to traditional Judaism and sought to outlaw them, they could not stop the movement. On the contrary, the initially marginalized Hasidim soon moved to the forefront of Jewish communal life throughout eastern Europe. Among the Hasidim arose masters (the tsadikim), who became a new communal and spiritual authority through whose mediation the requests and prayers of ordinary Jews could reach heaven. After the partitions of Poland (1772–1795), most tsadikim mimicked the dynastic form of power of their new tsarist Russian rulers and established their own dynasties. With their loyal entourage they settled in Podolia (Bar, Bratslav, Savran), Volhynia (Berdychiv, Korets, Shepetivka, Slavuta), and Kiev province (Chornobyl, Makariv, Ruzhyn, Shpola, Skvyra, Uman), where generally they favored smaller Jewish communities (shtetls) to bigger towns for their base. This allowed for better control of the population and for a more profound impact of their ideas on everyday Jewish religious life.

Reform movement and reaction to liberal trends

Despite their differences, by the outset of the nineteenth century, Hasidic leaders had come to form a kind of a united front with their fellow opponents, the Litvak mitnagdim. As Orthodox traditionalists, both were concerned with the challenge posed by the Haskalah (Jewish Enlightenment) and the Reform movement. Originating in the Germanic lands of Westphalia and Prussia, then rapidly spreading into the Habsburg Empire, Britain, and the United States, the Reform movement rejected the rabbinic tradition as terribly outdated, almost medieval, and not befitting the era of emancipation. In a sense, the Reform leaders reimagined Judaism as a religion only, something like Protestantism, rather than as an all-encompassing way of life. Also, they changed the language of the liturgy from biblical Hebrew to secular German; they eliminated as unpatriotic all prayers addressed to Jerusalem, the coming of the Messiah, and the return to the Holy Land; and they introduced other radical innovations in an effort to adapt Judaism to liberalized, emancipated, and modernized western European society.

Also originating in Germanic lands were liberal-minded Jews who felt the need to adapt Judaism to Europe's new socio-political challenges but who rejected the radicalism of the Judaic Reform movement. They were followers of Rabbi Zecharias Frankel, the father of Conservative Judaism. Frankel was a leading historian in a scholarly movement known as Wissenschaft des Judentums (Science of Judaism), which called for the evolution of a progressive form of Judaism that would be based on innovation and continuity, and not on revolutionary ruptures as argued by the Reformists. He subsequently became a professor at the Jewish Seminary in Breslau/ Wrocław, which is considered the cradle of Conservative Judaism. The label conservative may at first glance seem confusing. When initially adopted, it was appropriate in relation to the Reform movement, although it might seem to be a misnomer in relation to Orthodoxy, which by its very nature is conservative in orientation. A century later, in the United States, something called the Reconstructionist movement emerged from within the Conservatives. It was masterminded by the disciples of Rabbi Mordecai Kaplan, who argued for the need to create an all-embracing Judaic theology and practice.

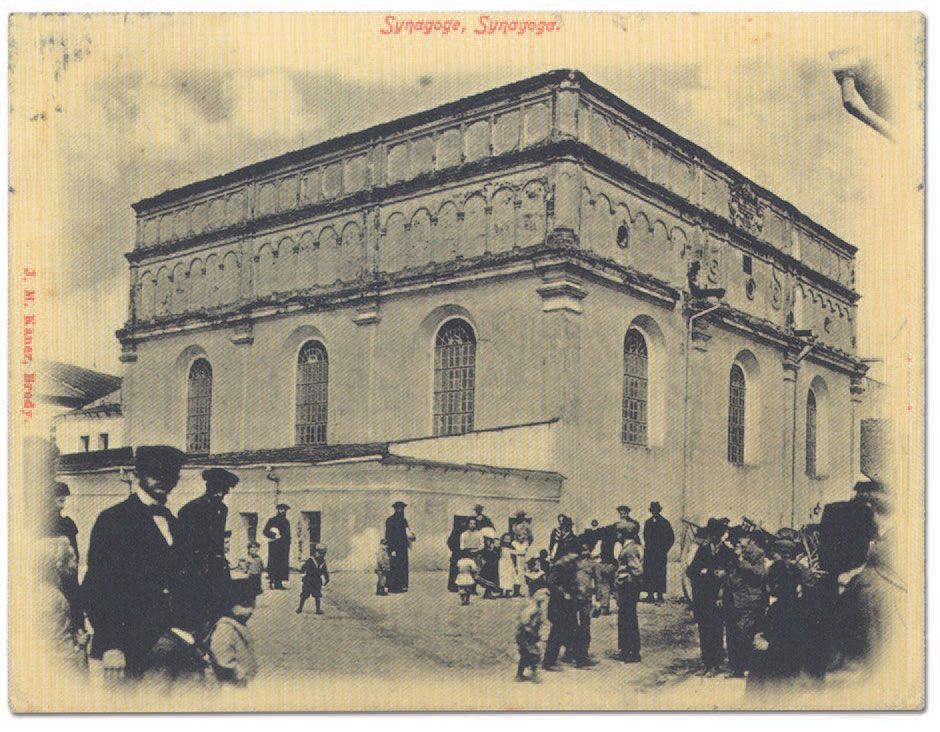

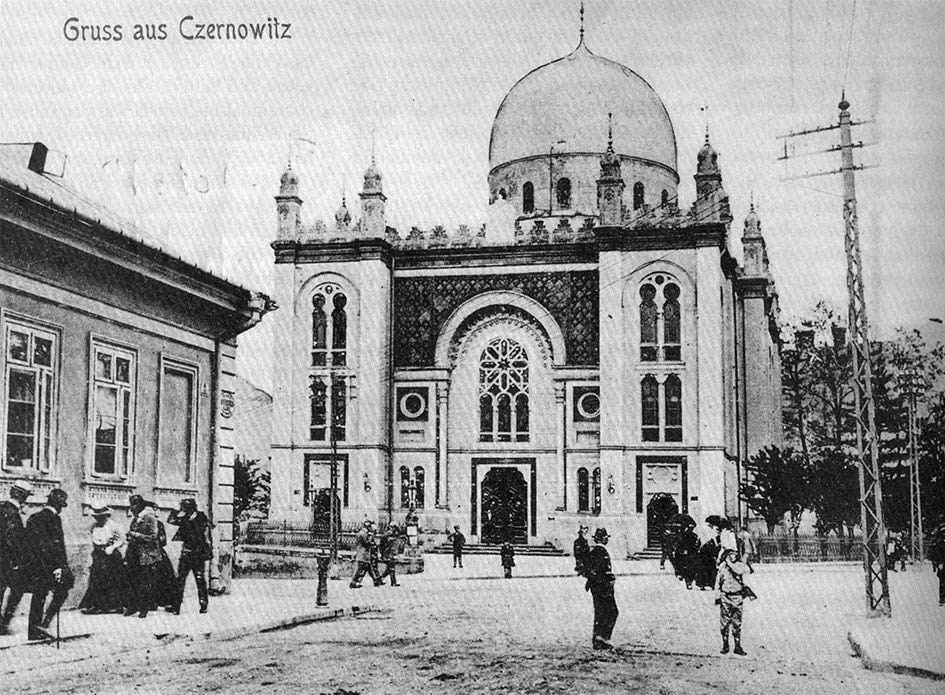

While thousands of descendants of Jewish immigrants from Ukraine living in Canada, Great Britain, and the United States have embraced one or another liberal trend in Judaism — Reform, Conservative, or Reconstructionist — back in the home country these movements have had very limited impact. New-style temples, sometimes called Progressive synagogues, with various elements of a Reform liturgy were established in Ternopil (1820s), Lviv (1846), Chernivtsi (1863), and Odessa (1863). Some of these synagogues imitated contemporary reconstructions of the Jerusalem Temple, while others were in the neo-Moorish style similar to that used for German Reform temples.

Most of the Progressive congregants were upper-middle-class Jews who had successfully integrated into the higher social strata of Austro-Hungarian, Polish (within the Russian Empire), and Russian society. The changes in liturgy were celebrated as a manifestation of their imperial loyalty. Nevertheless, the innovations, lavish style, and increasing non-observance of the Progressives went against the worldview of the majority of Jews in Ukrainian lands of the Russian Empire and Austria-Hungary. They remained traditionally Orthodox. Not only did they eschew contact with Jews of various liberal orientations, they actually considered them spiritually "unkosher" (treyf in Yiddish). Eventually, the reality of diversification created several large groups of practicing Jews who might attend services at either an Orthodox or a Liberal (Reform, or Conservative, or Reconstructionist) synagogue. Should, however, an individual switch from an Orthodox synagogue to a Liberal one, or vice versa, that would be considered a betrayal.

The representatives of the Haskalah in eastern Europe, known as maskilim, did not go quite so far as the Reform Jews. Instead, they remained traditional Jews although with broader secular interests. First and foremost, the maskilim sought to eliminate educational and social barriers between Jews and the surrounding Christian society by reforming Jewish education. They neither proposed a new theology nor formed a separate movement. Nevertheless, their desire to enlist the secular authorities as a major supporter and the help they offered the government in its attempt to control Jewish publications, education, dress, leadership posts, and other traditional communal pursuits made them quite dangerous in the eyes of the Orthodox.

Consequently, the Orthodox Hasidim and mitnagdim came together in an effort to convince the Russian and Austrian imperial governments that they, and not the reformist maskilim, represented the community as a whole. In the face of the reformist challenge, the Hasidim and mitnagdim came to embody an Orthodox Jewish community that opposed all changes, whether in the religious, educational, or communal sphere, seeing in novelty of any kind a potential breach through which the Reform movement could infiltrate its secular ways. Before long, Orthodoxy developed not only as a religious trend within Judaism but also as a political force, so that leaders of Jewish Orthodoxy in Austrian Galicia and Bukovina joined the Agudas Yisroel political party, which in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries defended its Jewish constituencies in the secular world. By the outbreak of World War I in 1914, most observant Jews in Ukrainian lands were Orthodox, either Litvak mitnagdim or Hasidim, although the very term Orthodox was avoided by them, since even it sounded too modern. Liberal trends in Judaism, such as the nineteenth-century Reform and Conservative movements and the twentieth-century Reconstructionist, Egalitarian, Progressive, and Trans-denominational movements, ultimately played a negligible role among the Jews of Ukraine. This was not the case, however, in the diaspora. Many of the descendants of Jews from Ukrainian lands who emigrated abroad integrated successfully in the United States, Canada, and Britain, where they joined liberal, modern, and post-modern trends of Judaism. Some of these liberal trends, as well as the more Orthodox versions of Judaism, have taken root in post-Communist Ukraine as a result of enlightenment work carried out by diasporan Jewish religious leaders and organizations. These various trends are often at odds with one another, since each competes in Ukraine as well as in the diaspora for funding and new members.

Karaites

Living for a thousand years alongside Jews in some parts of eastern Europe is a religious group linked to Judaism. This group, which came to be known as the Karaites (Karaim), declared itself the real chosen people, the Bnei Mikra (Sons of the Bible), while at the same time claiming that other Jews were not. The Karaites rejected rabbinic Judaism based on the authority of the Talmud and claimed that only the written text of the Hebrew Bible, and not the oral traditions attached to it, should be the basis for their new religiosity. Their religious practice was expressed through a particular liturgy and ritual laws established around a specific calendar. Although Karaites themselves denied their Jewishness, their rites and customs relied on and represented a close parallel to Judaism. By the eighteenth century, Karaites had established communities in Crimea (Chufut-Kale, Mangup, Gözleve/Yevpatoriya, Caffa/Feodosiya), in Volhynia (Lutsk), in Galicia (Lviv), and in Podolia (Derazhnya).

Since they considered Judaism irredeemably corrupted by the Talmud and rabbinic interpretations, the Karaites sought to create a purely biblical religion. To that end, they believe in a literal reading and often rigid interpretation of the Bible, one that allegedly is not mediated by any oral tradition. For example, they argue that, if the Torah forbids having a fire on Shabbat, this implies that they should dine in darkness and not have any lights prepared beforehand.

The Karaites reject the rabbinic prayer book and use the Book of Psalms instead. The Karaite's own legal regulations (ha-atakah) are in effect an alternative version, or reading, of the rabbinic laws that were also based on a distinct commentary or interpretation, albeit a different one. Once they needed to transfer their teachings to a new generation, they did so according to the laws of the Oral Torah, which they otherwise deny. Although small in number (about 13,000 in the entire Russian Empire and about 9,000 in Ukraine in the early twentieth century), the Karaites managed to convince the tsarist administration that they were not socially corrupt like traditional Jews and that therefore they were worthy of special privileges and exemptions. The success of their cause was in large measure due to the writings of the Karaite adventurer and scholar Avraam Firkovich, a native of Ukraine who spent many years working in Crimea until his death there in 1875 in the remote mountain-top cave town of Chufut-Kale.

The Karaites reject the rabbinic prayer book and use the Book of Psalms instead. The Karaite's own legal regulations (ha-atakah) are in effect an alternative version, or reading, of the rabbinic laws that were also based on a distinct commentary or interpretation, albeit a different one. Once they needed to transfer their teachings to a new generation, they did so according to the laws of the Oral Torah, which they otherwise deny. Although small in number (about 13,000 in the entire Russian Empire and about 9,000 in Ukraine in the early twentieth century), the Karaites managed to convince the tsarist administration that they were not socially corrupt like traditional Jews and that therefore they were worthy of special privileges and exemptions. The success of their cause was in large measure due to the writings of the Karaite adventurer and scholar Avraam Firkovich, a native of Ukraine who spent many years working in Crimea until his death there in 1875 in the remote mountain-top cave town of Chufut-Kale.

Judaism in present-day Ukraine

In the early 1990s, Orthodox (Litvak or mitnagdim) rabbis and Hasidic rabbis of different trends (Bratslav, Habad, Karlin-Stolin, Skvira) from the United States, Canada, and Israel started rebuilding Jewish religious life in dozens of Ukrainian cities and towns. Because of the extraordinary efforts of these leaders, not to mention the deep roots of Judaic Orthodoxy in Ukraine, most observant Ukrainian Jews belong today to Orthodox religious communities. The Reform movement also arrived from abroad, although it managed to form only a few congregations (sometimes called Progressive Judaism) of modest size in larger cities in Ukraine. There is only one synagogue of Conservative Judaism, and it came into being only in the first decade of the twenty-first century. The rebirth of Judaic religious life under the auspices of new rabbinic leaders does not imply that Jews in Ukraine have become strictly Orthodox, whether Hasidic or Litvak mitnagdim. While some young Jews do strongly identify with a specific trend, most of the others who are part of the revived religious life in Ukraine (at most 4 percent of the 90,000-strong Jewish population) see the mere association with a synagogue of any kind as a sufficient marker of their religiosity. This is also true for the approximately 1,200 Karaites, among whom less than 3 percent are observant. In other words, despite the revival and normalization of religious life in present-day Ukraine, the vast majority of Jews may have a cultural interest in Judaism, but they remain secular.

The above observation is perhaps true regarding Jews from Ukraine who have recently settled in diasporan countries abroad, since they, too, have largely remained secular. For those with religious tendencies, the first-generation immigrants usually join one of the various Orthodox congregations, whereas the second and third generation born and acculturated in the diaspora lean toward various liberal-oriented Reform or Conservative congregations. Only in Israel do immigrants from Ukraine, if not secular, join in albeit small numbers the plethora of traditional Orthodox communities in that country.

Click here for a pdf of the entire book.