Chapter 6.1: "Jews and Ukrainians: A Millennium of Co-Existence"

Jews and Ukrainians: A Millennium of Co-Existence is an award-winning book that explores the relationship between two of Ukraine’s most historically significant peoples over the centuries.

In its second edition, the book tells the story of Ukrainians and Jews in twelve thematic chapters. Among the themes discussed are geography, history, economic life, traditional culture, religion, language and publications, literature and theater, architecture and art, music, the diaspora, and contemporary Ukraine before Russia’s criminal invasion of the country in 2022.

The book addresses many of the distorted stereotypes, misperceptions, and biases that Ukrainians and Jews have had of each other and sheds new light on highly controversial moments of Ukrainian-Jewish relations. It argues that the historical experience in Ukraine not only divided ethnic Ukrainians and Jews but also brought them together.

The narrative is enhanced by 335 full-color illustrations, 29 maps, and several text inserts that explain specific phenomena or address controversial issues.

The volume is co-authored by Paul Robert Magocsi, Chair of Ukrainian Studies at the University of Toronto, and Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern, Crown Family Professor of Jewish Studies and Professor of History at Northwestern University. The Ukrainian Jewish Encounter sponsored the publication with the support of the Government of Canada.

In keeping with a long literary tradition, UJE will serialize Jews and Ukrainians: A Millennium of Co-Existence over the next several months. Each week, we will present a segment from the book, hoping that readers will learn more about the fascinating land of Ukraine and how ethnic Ukrainians co-existed with their Jewish neighbors. We believe this knowledge will help counter false narratives about Ukraine, fueled by Russian propaganda, that are still too prevalent globally today.

Chapter 6.1

Language and Publications

Ethnic Ukrainians today speak either Ukrainian, Russian, sometimes both, or a mixed Ukrainian-Russian fusion language called surzhyk. With regard to Ukrainian, the state language of independent Ukraine, it has a long history.

Spoken language

Ukrainian

The Ukrainian spoken language was formed as the result of long-lasting and complex interactions between three phenomena: (1) a number of dialects spoken by various tribal and ethnic groups inhabiting Ukraine in the past; (2) the written language of religious, secular, and legal literature — in particular Church Slavonic; and (3) the official languages of the states in which Ukrainians have lived: in the center and east of the country, Polish and Russian; in the west of the country, Polish and German in Galicia, Romanian in Bukovina, and Hungarian and Slovak in the Transcarpathian region.

Ukrainian is an Indo-European language of the Slavic-Baltic group, and within that context it is most closely related to other East Slavic languages: Belarusan and Russian. Ukrainian is spoken not only throughout much of present-day Ukraine but also beyond its current political boundaries, in particular in the immediately adjacent border areas of eastern Poland, southern Belarus, and the Voronezh and Kuban regions of southwestern Russia.

Because of the geographic homogeneity of the central and eastern parts of Ukraine, the various versions of Ukrainian spoken there have only minimal differences in vocabulary and pronunciation. Farther west, Polish influences are prominent in the Ukrainian language of Volhynia, Podolia, and Galicia, while Romanian influences are noticeable in the spoken language of Bukovina.

A real dialectal boundary separates southern Galicia and Transcarpathia from the rest of Ukraine. There, the chains of mountains, forests, and rivers created a variety of isolated linguistic enclaves. These geographic conditions, combined with the significant influence of Polish, Slovak, and Hungarian, prompted heated debates among linguists and ethnographers throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries about whether Galician is a distinct Ukrainian language and whether the Rusyn spoken in Transcarpathia is a distinct East Slavic language. The urbanization of Galicia as well as in-migration from other parts of Ukraine in the second half of the twentieth century brought Galician Ukrainian much closer to that spoken in the rest of the country. Nevertheless, the local spoken language, particularly in rural districts, has preserved its peculiarities and is generally referred to as the Western Ukrainian dialect.

Neighboring territories with inhabitants of different ethnic and linguistic backgrounds have had a crucial impact on the formation of the Ukrainian language and its dialects. For example, spoken Ukrainian came into being through interaction with non-Slavic languages, such as Turkic in the south and Romanian and Hungarian in the southwest; with West Slavic languages, such as Polish and Slovak in the west; and with East Slavic languages, such as Belarusan and Russian in the north and in the east. Although spoken Ukrainian developed in parallel with Belarusan and Russian, its formation has some distinct features.

Scholars distinguish five basic stages in the development of the Ukrainian spoken language. These include the earliest stage (to the eleventh century), when it was used by various tribal groups inhabiting the Dnieper River basin of central Ukraine; Old Ukrainian, used by a variety of social groups in the southern principalities of Kievan Rus' (until the fourteenth century); Early Middle Ukrainian, predominantly the language of peasants under Lithuanian and Polish rule (until the sixteenth century); Middle Ukrainian, spoken by Cossacks, peasants, and some Eastern Orthodox clergy and landlords (until the late eighteenth century); and Modern Ukrainian, dating from the early nineteenth century, when standard literary Ukrainian was gradually formed mostly on the basis of the southeastern dialect of the Poltava region. During the period between the tenth and eighteenth centuries, the Ukrainian spoken language developed several features that made it different from two other East Slavic languages, Belarusan and Russian. For example, Ukrainian came to eliminate the reduction of vowels, so much characteristic of the Russian language, and therefore transforming itself, as some linguists argue, into a very "vocal" language. Spoken Ukrainian also developed various forms of softening sharp aspirate consonants; in contrast to Russian, it has the phoneme h, which replaced a hard g, and it eliminated double and triple consonants in favor of vowel-consonant combinations, making the words easier to pronounce and the speech much more melodic. All these characteristics have led some to claim that Ukrainian, together with Italian, is the best European language for singing. Most important, oral Ukrainian has retained the rich morphology and phraseology of the rural population, which became the basis of various Ukrainian literary styles.

The process of urbanization in late-nineteenth and twentieth-century Ukrainian lands stimulated the formation of a new linguistic phenomenon — the so-called surzhyk. This is a fusion Russian-Ukrainian language of urban dwellers of the first generation, that is, the language of former Ukrainian-speaking village dwellers who came to cities and began speaking Russian. On the one hand, surzhyk showed the linguistic resilience of the former peasants who had resettled in big cities, but on the other it revealed the degree to which Russian was imposed as the obligatory language of everyday usage in Ukraine. Since the majority of the population resides in urban areas, some argue that surzhyk is the most widely used "language" in present-day Ukraine. Nevertheless, it is frowned upon by users of standard Ukrainian and is the frequent butt of jokes that poke fun at linguistic assimilation and russification.

Nowadays the Ukrainian spoken language is used unevenly throughout the country, a phenomenon that reflects the country's colonial past. While most industrialized cities in central, southern, and eastern Ukraine (Dnipropetrovsk, Odessa, Donetsk, Kryvyi Rih, Zaporizhzhya, and Kyiv) remain predominantly Russian-speaking areas, Ukrainian retains a firm presence in western Ukraine (Volhynia and Galicia) and in rural areas throughout the country. According to 2001 data, while only 10 percent of the population in Crimea and 23–30 percent of the population in the southeast (Donbas) speak Ukrainian, the figure is as high as 80 percent in central Ukraine and 89–97 percent in Volhynia, Galicia, and Bukovina.

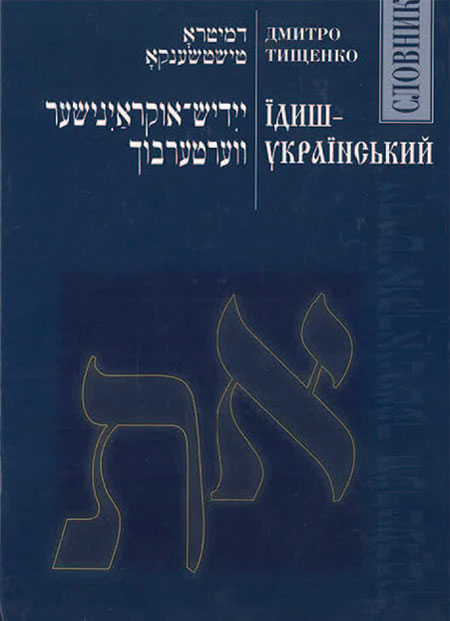

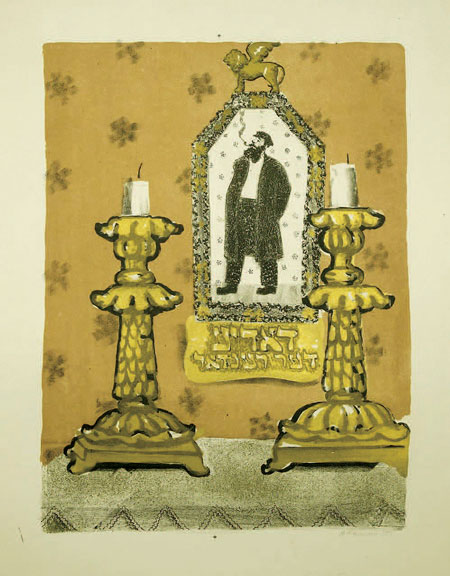

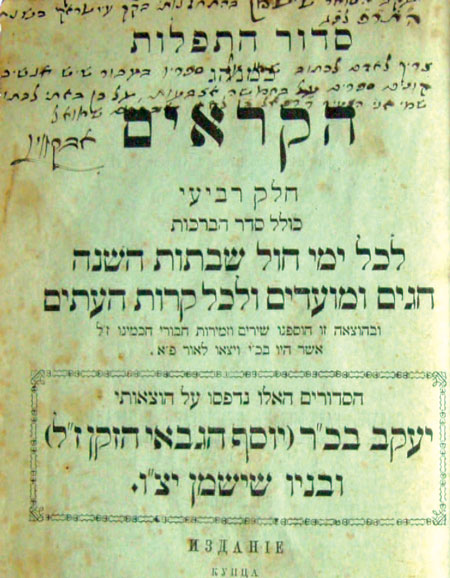

Yiddish, Hebrew, and Crimean Jewish languages

Traditionally, Jews in Ukraine had at their disposal two languages for internal usage: Yiddish, as the mameloshn (mother tongue); and Hebrew, as the loshn koydesh (holy tongue). Hebrew was predominantly a written language, although it was always used for reading prayers aloud. Moreover, the rabbinic elite sometimes used it for sporadic oral communication. Jews were also multilingual: the elite Jews who had to deal with non-Jewish authorities and the Jewish women trading in the marketplace could speak sufficient, although not necessarily correct, Polish, Russian, and Ukrainian in order to communicate with the Polish nobility, the tsarist Russian administration, and their ethnic Ukrainian peasant neighbors and customers. In Galicia and Bukovina, Jewish merchants and traders could also speak German and sometimes Romanian or Hungarian. Yet the mother tongue for most of these Jews remained Yiddish. Even at the height of modernization in tsarist Russia in the late 1890s, 97 percent of all Jews there indicated Yiddish as their first language and as much as 60 percent knew only Yiddish.

What is Yiddish exactly? Initially, it emerged from the northern Rhine dialect of medieval German. Written in Hebrew characters, Yiddish subsequently became a fusion language, a kind of trans-European traveler that absorbed, digested, adapted, and refashioned elements of various other languages. Among these elements were those from traditional Jewish languages such as Semitic Hebrew and Aramaic, as well as from the Germanic, Romance, and Slavic languages with which Ashkenazic Jews came in contact in Europe. Yiddish enriched these borrowed elements with vocabulary and phraseology from Hebrew that was used in education, business correspondence, and liturgy, and also from Aramaic used in Talmud study. One leading scholar (Benjamin Harshav) referred to Yiddish as a Germanic language based on Slavic vocabulary living in a Hebrew library. The point is that none of these variegated linguistic elements could be separated from Yiddish without undermining the very texture of the language.

There is much controversy about where and when Yiddish emerged. Most scholars agree that Yiddish sprang up as a contact language when Jewish migrants from Palestine came through the Italian peninsula and settled in the Rhineland, where they were exposed to medieval Germanic dialects. For example, the famous eleventh-century commentator on the Bible and the Talmud, Rashi (acronym of Rabbi Shlomo Itshaki), used words from medieval French as well as from German (in Hebrew transliteration) in a form very close to what we call Yiddish. When, in the thirteenth to fifteenth centuries, Jewish migrants who spoke a northern Rhine dialect of medieval German moved through central to eastern Europe, they absorbed elements from Slavic languages, especially Polish, Ukrainian, and Russian, so that their Yiddish became a fusion language par excellence. Eventually, Yiddish became the common tongue — and key cultural marker — for all Ashkenazic Jews in Europe.

Because of its complex fusion character, special linguistic skills are required to dissect the multilingual parts of a Yiddish word. For example, in the title of the famous Sholem Aleichem story, "Der farkishefter shneider" (The Bewitched Tailor), the word farkishefter has a Germanic prefix and suffix (ver- and -ter in modern German), a Hebrew root (k.sh.f., meaning magic or witchery), and a strong presence of vowels reflecting the significant impact of a Slavic-speaking environment.

The use of borrowed words reflects the particularly flexible nature of Yiddish. Hence, words with similar meaning yet of different origin co-exist but convey different nuances. Hebrew words taken directly from Hebrew books or Aramaic texts were considered high style, those of German origin conveyed a neutral style, and those of Slavic origin reflected a popular and more intimate manner of speech. For example, there are three Yiddish words for "question." Leaning over a Talmud, the Yiddish-speaking rabbi would mock his student: Iz dos take a shayle? (Is this really a question?). The emancipated Jew, as in an 1887 book by Shimon Bikerman, might, when discussing issues of feminism, be referring to der zhensker vopros (the woman's question). The Yiddish-speaking Marxist would speak of di natzionale frage (the national question). Although the three Yiddish words for "question" — reflecting Hebrew (shayle), Russian (vopros), and German (frage) origins — all mean the same thing, the word choice depends on the different contexts.

Spoken Yiddish is generally classified into two broad categories: Western, used by Jews in German lands (including Bohemia and Moravia); and Eastern, used by Jews in Slavic lands as well as in historic Hungary and Romania. The Eastern linguistic sphere is divided into three dialects: Northeastern (Lithuanian) Yiddish, Southeastern (Ukrainian) Yiddish, and Mideastern (Polish) Yiddish, each of which was found in parts of present-day Ukraine.

Northeastern (Lithuanian) Yiddish extends into Ukraine's northern and eastern regions: Polissia and the former tsarist provinces of Kharkiv and Katerynoslav. This is largely the result of the migration of Jews from Lithuania and Belarus into southeastern Ukraine from the 1860s through 1880s. Southeastern (Ukrainian) Yiddish covers the bulk of central and southern Ukraine, encompassing the historic regions of Volhynia, Kiev, Poltava, Podolia, Bukovina, Bessarabia, and Crimea. The variants of Yiddish spoken in Volhynia and Podolia are especially and heavily influenced by the local Ukrainian dialects of those regions. Finally, Mideastern (Polish) Yiddish covers western Ukraine, that is, Galicia and Transcarpathia, as well as all of present-day Slovakia, Hungary, western Romania, and much of Poland. Not surprisingly, the Mideastern Yiddish dialects have been strongly influenced by either Polish, Hungarian, or Romanian.

Following World War II and the Holocaust, Yiddish was rarely heard as a spoken language in Soviet Ukraine's cities. It was, however, still used in towns, particularly former shtetls, where, in the absence of strict governmental control, Yiddish remained the spoken language of observant Jews and the few remaining Jewish artisans (kustari). In several towns, particularly in Galicia and Bukovina, the one remaining synagogue became a place where Soviet Jews could speak Yiddish outside the home. Despite the attempts of the Soviet authorities to russify Jews, at least 7 percent of Ukraine's population declared Yiddish as a first language in 1989. This was the height of the Gorbachev era, when four times more people turned to the study of Yiddish than to Hebrew.

After the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, the trend toward Yiddish was undermined in the wake of the massive emigration to Israel. As a result of imminent departure, there was a high demand for Hebrew, leading to the establishment of dozens of Jewish Agency (Sokhnut)-sponsored intensive Hebrew-language programs (ulpans). The claims of some government-supported and anti-Zionist-minded Jewish leaders that Yiddish, not Hebrew, should serve as the language of identification for the Jews of Ukraine turned out to be mere wishful thinking.

Very little is known about the way the rabbinic elites and members of proto-Zionist circles (who called themselves Palestinophiles) used Hebrew as a spoken language. Most likely, the spoken Hebrew of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries in Ukrainian lands was based on formulaic statements from rabbinic literature, Talmudic phraseology, and flowery phrases from secular, mostly maskilic (Jewish Enlightenment) writings. Pronunciation was typically Ashkenazic, evident from the manner in which the Hebrew-language Torah texts were read during synagogue services. This is in contrast to the Sephardic pronunciation adopted later in the modern State of Israel.

In contrast to most Ukrainian territories, the Jews/Krymchaks and the Karaites of Crimea did not use Yiddish. The Jews of Crimea initially spoke a local Byzantine dialect of Greek, but after the Ottoman conquest of the coastal regions in 1475, they began to use a Turkic-Kipchak language, specifically a variant of Crimean Tatar which was called Krymchak. As for the Karaites, they too spoke a form of Turkic Kipchak that was close to Crimean Tatar. The language was called Karaite and evolved into three dialectal forms determined by the geographical location of the speakers: Crimea, Galicia (Halych-Lutsk), and Lithuania (Trakai). In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, Karaite functioned as a Turkic-Kipchak literary language written first in the Hebrew alphabet, then in the Cyrillic alphabet for the Karaites in the Russian Empire (Crimea and Lithuania) and the Latin alphabet in its Polish form for those living in Galicia. The language of the Jews/Krymchaks and Karaites of Crimea also acquired many Italian words (from the Genoese in Caffa and other Black Sea ports) as well as Yiddish words brought by Ashkenazic Jews who began to settle in the peninsula, albeit in small numbers, in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

Written language

The written language (or languages) used by any given people have often differed from spoken language. For example, the French, Germans, Italians, and other peoples in western Europe had for centuries used Latin as their written language. Analogously, many peoples in southeastern and eastern Europe, most particularly those within the religious and cultural sphere of Eastern Orthodoxy (Serbs, Bulgarians, Ukrainians, Russians, among others), used a liturgical language called Church Slavonic for written texts.

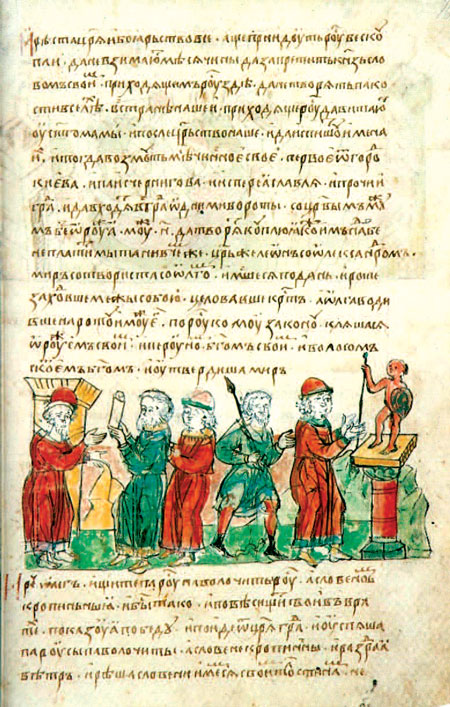

Church Slavonic

The origins of Church Slavonic are commonly associated with the imperial Byzantine envoys, later declared saints, Constantine/Cyril and Methodius, who in the second half of the ninth century brought Christianity to the Slavs and created for them an alphabet. Their mission was actually directed toward the West Slavs (modern-day Slovaks and Moravian Czechs), although neither the Eastern-rite Christianity they introduced nor the alphabet they devised (Glagolitic) survived for very long in those regions. Rather, it was among some of the South Slavs and in particular East Slavs that the work of Cyril and Methodius not only survived but flourished. Their Christian disciples in the Bulgarian Empire devised a new alphabet based on Greek, which they named — in honor of St Cyril — the Cyrillic alphabet. It is this writing system that was used for Church Slavonic texts, and in a modernized form it continues to be used by Ukrainians, other East Slavs, and some South Slavic peoples.

Church Slavonic was a language that no one spoke as a "natural," living mode of communication. Nevertheless, Church Slavonic texts could not help but be influenced by the environment in which they were produced. Those influences took different forms, including vocabulary from the spoken dialect of a given author/compiler or from the official language of the state. Hence, Church Slavonic texts produced between the fifteenth and seventeenth centuries, when Ukrainian lands were in Poland-Lithuania, are likely to be filled with Polish words used at the time in urban settings, as well as with Latin words because of the educational training of the author. Analogously, when after the mid-seventeenth century Ukrainian lands were gradually incorporated into Muscovy and later the Russian Empire, Russian influences were increasingly found in Church Slavonic texts by authors from Ukraine.

Although there were some early efforts at producing texts that were based on the local spoken vernacular, Church Slavonic and to a lesser extent Polish and Latin remained the main written languages used in Ukraine until the late eighteenth century. From that time on, there was a slow but steady increase in the number of texts that were based on spoken Ukrainian vernacular, the first landmark in this development being a literary work called Eneyida (1798) by an author from central Ukraine, Ivan Kotlyarevskyi.

Ukrainian language and government policy

The vernacular trend was given particular encouragement during the first decades of the nineteenth century. This was a time when two phenomena reached Ukrainian lands from western and central Europe: the Romantic movement (with its emphasis on the unique value of each language and culture worldwide); and the ideology of nationalism, which argued that spoken language conveyed the very essence of a people and its national identity. Armed with the conviction that language was the ultimate defining characteristic of an individual's ethnic identity, the proponents of nationalism — the so-called nationalist intelligentsia — began to speculate about which particular language might best serve as the written word for the people they presumed to represent. This was the birth of the language question.

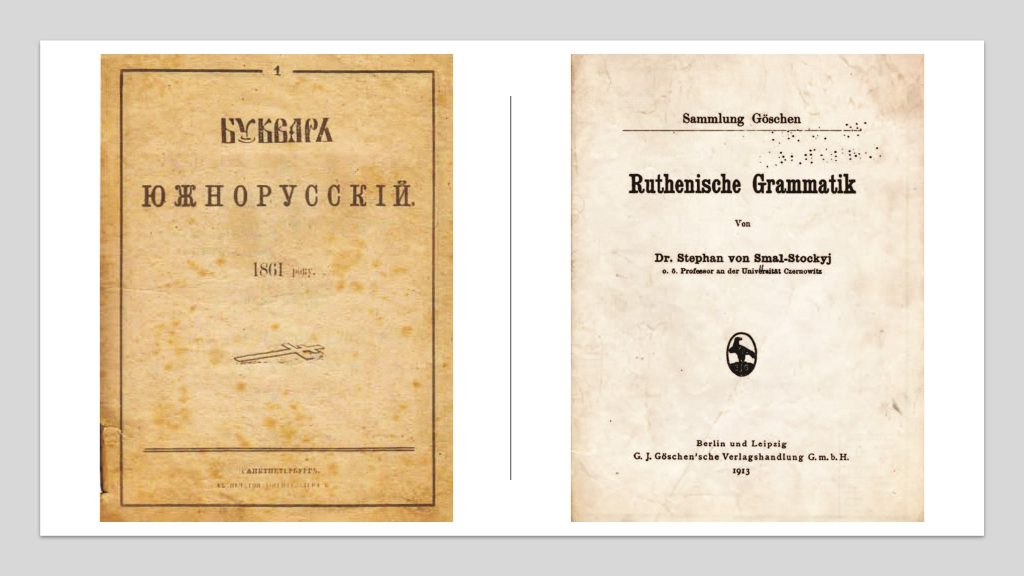

On Ukrainian lands within the Russian and Austro-Hungarian empires during the long nineteenth century (1780s–1914), the language question took the form of debates between supporters of either Church Slavonic, Russian, or the Ukrainian vernacular. Supporters of Church Slavonic and of Russian argued that both those languages had the proper dignitas (dignity): Church Slavonic, because it was the language of sacred religious texts used in church; Russian, because it was the language of a powerful empire and lingua franca (common mode of communication) of its urban environment — in short, the source of "higher" forms of culture and knowledge. On the other hand, in the spirit of Romanticism, proponents of Ukrainian argued that the spoken vernacular should be the basis of the group's written language, because, as the language of the people, it was considered the very heart and soul of what constituted the Ukrainian nationality.

In the Russian Empire, these two contrasting views were symbolized by the choice of language used by Ukraine's two greatest writers in the first half of the nineteenth century: Taras Shevchenko, who chose vernacular Ukrainian; and Mykola Hohol/Nikolai Gogol, who chose Russian. In the end, intellectual debates about which written language to use were brought to an end through intervention by the state authorities. By mid-century, Russian intellectual circles and then the imperial government began to view the language question through the prism of politics, that is, to equate the idea of a distinct Ukrainian (officially called Little Russian) language with territorial and national separatism. Therefore, the tsarist authorities undertook draconian measures to avert any possible danger to the state: in 1863 and 1876 government decrees banned all publications, school instruction, and theatrical performances in the Little Russian "dialect" (Ukrainian language). Even in Orthodox churches the Church Slavonic liturgy was to be chanted using the Russian instead of the more natural Ukrainian pronunciation. Despite the generally lax enforcement of the decrees by the local authorities, the restrictions against the Ukrainian language remained formally in place until the collapse of the Russian Empire in 1917.

In the Habsburg-ruled Austro-Hungarian Empire, the intelligentsia was also divided, in this case between supporters of using either Church Slavonic, Russian, or vernacular Ruthenian (the official Austrian term for the Ukrainian language and for ethnic Ukrainians). And, here again, language became intimately interrelated with national identity. The Ruthenians in Austrian Galicia and Bukovina and the Carpatho-Rusyns in Hungarian Transcarpathia who favored using the Russian language (Russophiles) did so because they believed they were of the Russian nationality. Analogously, those Galician and Bukovinian Ruthenians (Ukrainophiles) who favored using the Ukrainian language believed they were members of a distinct Ukrainian nationality. Each orientation, together with the pro-Habsburg Old Ruthenians (Starorusyny), rejected the alleged nationality and language choice of the other.

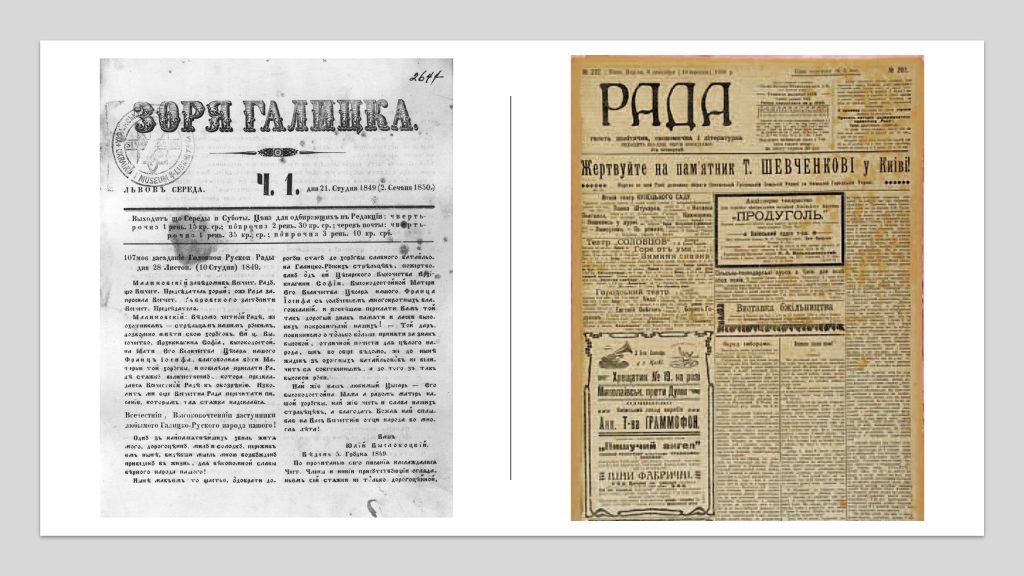

Since there were no restrictions on language use, at least in the Austrian "half" of the Habsburg Empire, the Ruthenian press flourished in the province of Galicia and, to a lesser degree, in Bukovina. The group's first newspaper Zorya halytska (The Galician Dawn), which began in the context of the Revolution of 1848, continued to appear for a decade. Before the end of the century, a whole host of newspapers, magazines, and journals of various national and linguistic orientations bore witness to the vibrancy of Galician-Ruthenian civic and cultural life, including Slovo (The Word) and Halychanyn (The Galician) representing the Old Ruthenians; Dilo (Action), Bukovyna, and Literaturno-naukovyi vistnyk (The Literary and Scholarly Herald) for the Ukrainophiles; and Golos naroda (The Voice of the People) and Prikarpatskaia Rus' (Carpathian Rus') for the Russophiles. Despite their tolerance toward local languages, the Habsburg authorities nevertheless did take a stance on the language question, issuing in 1892 a decree regarding which form of the Ruthenian language would be acceptable for use in state schools. The decision was in favor of the vernacular-based language supported by those of the Ukrainian orientation.

In stark contrast was the situation of the Ukrainian press in the Russian Empire, which was stifled because of tsarist restrictions (1863 and 1875) against all publications in "Little Russian" (Ukrainian). After the Revolution of 1905, imperial Russia's authorities relaxed censorship enforcement for a while, allowing for the appearance of the first Ukrainian-language newspapers (Hromadska dumka/Civic Thought and Rada/The Council, among the first of several) during the few years on the eve of World War I.

In the twentieth century, the language question was less a debate about which one of several different languages was the most appropriate than a struggle to determine which variant of the Ukrainian literary language should be adopted as the standard. What, for instance, should be done with the pre-World War I literary language developed by the Ruthenians/Ukrainians of Austrian Galicia, which included local dialectal forms and vocabulary as well as borrowings from Polish, and to a lesser degree German, especially administrative and legal terminology?

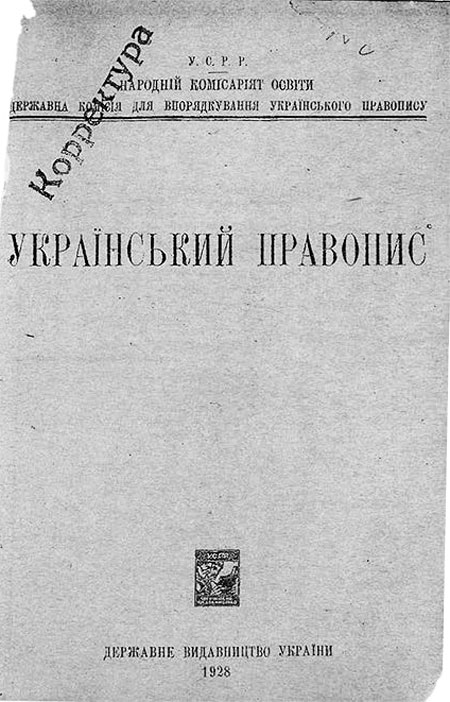

When Soviet Ukraine came into existence and the new regime (at least in the 1920s) supported efforts to codify the widespread public use of a Ukrainian literary language, the Galician variant was for the most part rejected in favor of the eastern variant, popularly assumed to be the language of Shevchenko. Then, in the 1930s, when the Soviet Union entered a period of increasing regimentation and ideological control over scholarly and cultural activity, the language-standardization efforts of the previous decade were scrapped; gradually the Ukrainian literary standard incorporated many russianisms as part of an ideologically inspired state policy to bring the three East Slavic languages closer together.

In the end, by the second half of the twentieth century, there were two variants of the Ukrainian literary language: the "eastern," increasingly russified variant that became the standard for most urban areas in Soviet Ukraine; and the "western" (with some elements from the pre-war Galician standard and showing a degree of acceptance of the Soviet reforms of the 1920s), which was used in interwar Polish-ruled Galicia and among Ukrainians in the diaspora. The differences between the "eastern" and "western" variants can sometimes be substantial, as in the Ukrainian word for Jew (see text insert, p.7).

After Ukraine became independent in 1991, the question immediately arose as to which of the country's two most commonly used languages — Ukrainian and Russian — should become the "official" medium. In 1996 Ukraine's new constitution proclaimed Ukrainian the state language, while at the same time providing guarantees that other languages (Russian, Polish, Romanian, Hungarian, etc.) could be used in the local administration and schools in areas where speakers of those languages live in large concentrations.

Despite the provisions of the 1996 constitution, the language question has not gone away. Currently, the debates center on what might be called internal linguistic and external socio-political matters. On the one hand, the efforts to create a new literary standard inevitably provoke debates about linguistic issues (alphabet, spelling system, etc.), including the degree to which Soviet-era russianisms, especially in vocabulary, need to be removed. On the other hand, language has become a bone of contention between those who support affirmative-action measures to enhance the overall status and use of Ukrainian, versus those who believe that Ukraine should have two equal state languages: Russian and Ukrainian. It is interesting to note that many ethnic Ukrainians themselves as well as Ukrainian citizens of other national backgrounds are divided on this issue: some favor speaking Ukrainian and sending their children to Ukrainian-language schools; others favor using Russian for the same purpose.

Click here for a pdf of the entire book.